Interviewsand Articles

Insiders and Outsiders -: Leta Ramos and the Creative Growth Art Center

by Richard Whittaker, Apr 19, 2019

One afternoon Leta Ramos took me down to Oakland’s Creative Growth Art Center, a place I’d heard spoken about enthusiastically, but hadn’t visited. The center is devoted to helping mentally, physically and developmentally disabled adults through art making. The 100-plus clients at the center have a wide range of art materials and tools at their disposal, all the studio space needed along with oversight and instruction. In its 25-plus years of existence, the CGAC has become a model for how art making can be a powerfully transforming avenue for growth in this population. Making art, it turns out, is a special medicine. One needn’t be an expert to see, in the focus of individuals so engaged, that a door stands open to hidden worlds beyond ordinary reach.

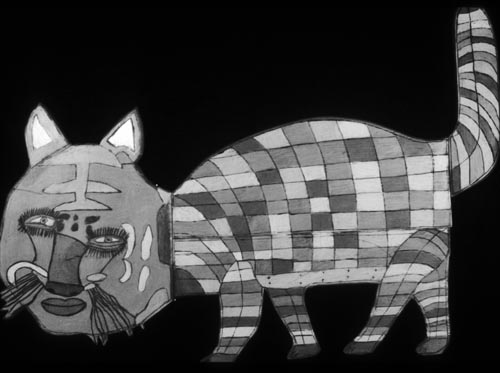

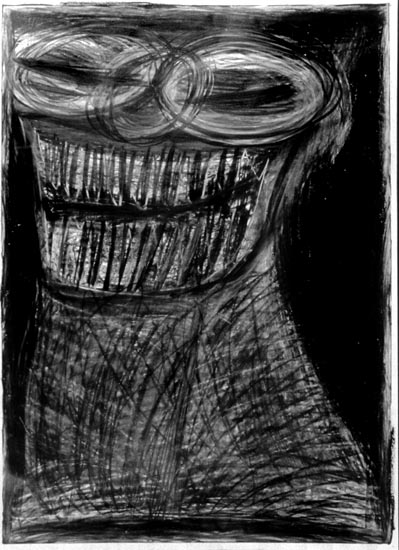

In most of the articles I’ve read about the center, the works produced there are referred to as “outsider” art. Outsider artists, it’s explained, are self-taught and their work is not indebted to art historical reference. All this is often taken to mean that such artists “can’t draw or paint very well.” But whatever else might be said about the art produced at the center, one feels no distance exists between the work and the artist’s interior world—each one idiosyncratic, often fascinating and sometimes disturbing.

In buying a print, drawing, painting, ceramic object or hooked carpet at the center’s gallery one is supporting a good cause. The sophisticated buyer knows that the painting with the odd human lips and eyes on the animal’s face is not a flaw like a dent in the side of a new refrigerator. That left turn in mid-stream from cat face to human face is one of those uncalculated quirks you see a lot of in outsider art. Encounters with such art put one at an interface between two worlds. And where other artists may struggle to find an open passage to this hidden realm, here it appears to be the starting point. The energy felt at this border between the familiar and the unknown fairly radiates from the work on display at the center. And the “outsider” tag provides some distance from the unsettling ontological realities that one might feel behind the works themselves.

Sales are an important source of income for the center, and since a portion goes to the maker, each sale is also a powerful therapeutic affirmation. It’s a happy fact that the cash dollar speaks clearly, even across the divide from insiders to outsiders.

I first heard about the Creative Growth Art Center from a close friend, an indomitable free spirit, Peggy Williams. As a college student, she’d taken art classes and found that when she painted she became so manic she began to fall apart from lack of sleep. She struggled with this for some time, but the creative energy unloosed was simply too powerful. Although she stopped painting, she retained a strong feeling for the kind of art that’s openly expressive, exuberant, colorful and personal—often typical of outsider art, in other words.

When I met Peggy, she owned a restaurant in Alameda, an oasis of sorts, with a little art gallery upstairs where she hosted openings for local artists. Years before, when she’d first moved to Alameda, right away she began trying to wake the community up. She opened a little coffee shop and introduced something that had never been seen in Alameda—espresso.

I remember her asking me one day, if I’d ever been to the Creative Growth Art Center in Oakland. When I replied that I hadn’t, she put her hands on her hips and fixed me with a hard look. “You get over there right now! What’s wrong with you?!”

That was Peggy.

Another time I remember her having come back from the CGAC with a haul of artwork. She could hardly contain herself. “I’ve got to stop going over there! I’m going to go broke!” Then she would just shake her head and say, “I can’t tell you how wonderful that place is!”

I know nothing of the role her own disability—a paralyzed right arm from polio— might have played in her feelings towards the center. She paid this inconvenience no heed at all. In fact, it was only noticed when someone reached out for a handshake. Then Peggy would hoist her right arm with a swing of her hips and a little help from her left arm to get her hand into position.

I always felt that Peggy was an example of a true insider. The art at the Creative Growth Art Center was just the visible evidence of something she already knew about intimately.

Leta Ramos is another one of those people. A year had passed between my first meeting her and the appearance on my answering machine of a message to call her. Remembered most clearly from the first visit was her immediate and loquacious friendliness. Leta talks, she touches, she crosses over into your space. As Henry Miller said, “One learns more about someone by talking to them than by listening to them.” I think this is Leta’s method. Not that she doesn’t listen.

One runs into certain people, often among artists, I find, of whom you might say, he or she is “quite a character.” The chance to be around such individuals makes life more interesting.

When I finally got Leta on the phone, she told me, “I’ve got a couple of important ideas I want to tell you about.” We got together and she took me to the Creative Growth Art Center for a second time.

“I’ve gotten thirty-eight artists, all friends of mine, who have agreed to participate in a program at the center called “Inside/Outside.” They’ll each contribute their time and art to work with people at the center. They’re all very respected artists. The first one is Manuel Neri and Sam Richardson is the next one. It’s wonderful, and I just want to get this information out!”

This meeting was followed up with more phone conversations, a couple of lunches, car rides, then conversation at her home with my questions about all the paintings on the walls. There was a tour of their studios, with descriptions of what was what, with the whens and hows. Then there were more visits to the Creative Growth Art Center with introductions to everyone—directors, instructors, and the clients, most of whom Leta obviously knew well.

Leta’s husband is painter Mel Ramos, and over the years she’s met and become friends with a substantial cross section of notable artists in the Bay Area. There are stories—the cross-country drive with Wayne Thiebaud, conversations with Salvador Dali and being cold-shouldered by Gala. In Rome there was the adventure with Gina Lollobrigida. “She had to have the dress off my back! This was for an upcoming movie! It was just a very simple, but revealing dress. Gina said, ‘There’s nowhere in Italy I could get a dress like that!’” And, “Gina didn’t like Sophia Loren.” Leta confided—“‘That cow,’” she called her.”

Leta’s stories were entertaining, and I needed to be persuaded to put something together in the magazine to help the center.

For many years Leta taught elementary school (She must have been an exceptional teacher.) Her own children were in school as well as those of her friends, and she cared deeply about the quality of their education. At time Max Rafferty was California’s Superintendent of Schools. As Leta put it, “His policies were a disaster.” When Wilson Riles Jr. ran for Rafferty’s office, Ramos organized an art auction with her artist friends. It was a huge success and the money helped Riles win the election.

The wellbeing of children came up in other ways. One of her projects was a series of stories that was to be put together about the children of famous artists. She knew a lot of them. They often had a hard time with identity issues, she confided. How to bring some healing into this area?

It was easy to see that the disabled individuals at the CGAC were like children to Leta. It turned out that her oldest son, now no longer at the center, was born with Down’s syndrome. She told me about a painting he did, one of her favorites. It was included in an exhibit at the center and a man wanted to buy it. She described her struggle whether to sell it or keep it. But sold, she could give the $50 dollars to her son—real money earned by his own hands. She allowed the sale and told me about the deep impact giving the money to her son had. It had made up for the loss of selling it.

A year and a half ago Leta had a tumor removed from her brain. She told me about the damage that had been passed down to her as a result of her grandfather’s injuries in WW1. Mustard gas. The grandfather hadn’t realized how it might have factored into his grandchild’s Down’s Syndrome—and maybe Leta’s tumor, too.

After the surgery, there was trouble with balance, loss of memory and an impact on emotional functions. How was she to come back? She still hadn’t taken up her own painting again. Still, I wouldn’t have guessed anything was wrong if she hadn’t told me.

But, as Leta would say, “In any case, life is too short for complaining!” Dwelling on the negative was not going to help. The tumor was gone and there were projects that needed to happen. The center needed support. People needed to know about the time and work that artists like Manuel Neri and Sam Richardson and 36 other artists were going to donate. Word had to get out.

In thinking about Leta Ramos, I am imagining the art world expanded, infiltrated, bisected, and thoroughly criss-crossed. Outsiders or insiders? It’s not a question to worry about.

About the Author

Richard Whittaker is the founding editor of works & conversations and West Coast editor of Parabola magazine.

SUBSCRIBE NOW

TO OUR MONTHLY NEWSLETTER

Share Your Comments and Reflections on this Conversation: