Interviewsand Articles

Carlo Ferretti's Cove

by Richard Whittaker, Oct 6, 2003

Mr. Ferretti was apologetic, but yes, if I didn't mind entering a construction zone, we could meet at his home which was not so far away. He was doing some remodeling, he explained. Something about the way he spoke reminded me of an impression I'd gotten from his email notes. A kind of gentility, a degree of understatement perhaps, a manner from a different culture.

Of the photos he'd sent me of his work, one stood out, a piece of public art he'd completed in the town of Albany where he lives, a small community just north of Berkeley. On the phone giving me directions, he told me his house was "behind some greenery." He added, "It's hard to see. Just look for the house with all the"—he searched for the right word—"it's like a screen." I felt sure I was going to like Mr. Ferretti.

A few days later, as I headed down the little street on which he lived, I looked forward to our meeting. In a neighborhood of modest bungalows, I looked for the discontinuity I expected to see, and there is was, a green effulgence rising up above the other lawns, ahead on the right.

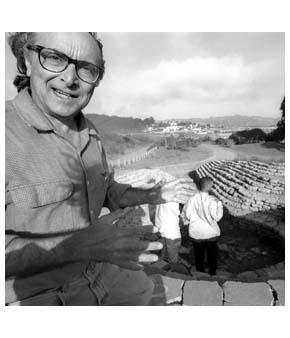

At the front door a smiling man wearing large horn-rimmed glasses invited me in. He must have been in his fifties, not a big man, and with the quiet way of speaking I'd already heard on the phone. After a handshake and greeting, I began right away with my questions.

Mr. Ferretti described his life in Rome where he'd been born, and how his ambition had been to attend the University of Rome to study architecture. He had succeeded in making his way into the university, but it turned out to be a disappointment, as he told me. His vision of architecture had been one of art and architecture--but in his course work there, the study was disclosed as something more mundane. Not only that, classes were routinely delayed for weeks at a time and when finally began, were vastly overcrowded. "I had to do a lot of things on my own," he told me. "Bruno Zevi was the only instructor there who made architecture come to life, although I disagreed with much of what he said." Ferretti characterized Zevi as a formalist. Still, in Zevi, Ferretti found someone who responded encouragingly to his own sensibilities.

I found myself wanting to hear more of Ferretti's views about architecture. "Have you seen the Pantheon?" he asked me. [Yes.] "Okay. Now forget whatever you've read about it. Just imagine you're standing inside the Pantheon. What is the Pantheon?" In the silence that followed, he continued. "Think of those columns of the Greek temples. What are they?"

I was trying to think. The question was unexpectedly basic, and demanded a fresh point of view. Nothing was coming to me, and Ferretti continued.

"It took me a long time to understand what architecture is." He said, as if to underline the question he'd put to me.

"Okay, what is it?" I challenged, curious to see what he would say.

"I can't tell you," he said with a laugh, as if I should have understood that much. "In some of Louis Kahn's notes, where people say he's incomprehensible, I think he actually found the best way to say it."

In our conversation, Louis Kahn came up repeatedly, along with Bernard Rudofsky. These two men, it was clear, were held in highest esteem. "In architecture, Louis Kahn got rid of the fog of modernism," Ferretti told me.

The fog of modernism.

It was clear Ferretti had thought deeply about these things. "I could go on and on," he added half apologetically, with a gesture I recognized as Italian. "My wife listens to me; she's the only one."

A Small Tour

As we walked around talking, I noticed several paintings and drawings on the walls—his own, it turned out. He favored a primitive style. There were human figures and animals that might have been taken from the walls of caves—and there were cows, the heads of cows especially, simplified and rendered as line drawings - crowds of cow-faces staring out at the viewer with expressions difficult to read.

I was intrigued by the cows. What did these drawings say? Comedy? It didn't seem so. Pathos? No, I couldn't find that, either. Absurdity? The faces disclosed no ironic intent. They occupied some ground very close to neutral. If they were meant to represent us, the human herd, the portrait was not one of censure. As I stood studying one particular drawing, a reading of it continued to elude my scrutiny. But soon we were moving on and through the kitchen - currently demolished and on its way to being reborn - and heading outside, I was obliged to drop my interrogation of his drawings to keep pace.

Soon we were in a small back yard. Picking my way through broken concrete and miscellaneous scrap from the remodeling work, I spotted a building of recent construction sitting flush against the back property line. Made of concrete block and wood, it had large windows wrapping front and side walls. Ferretti explained he'd built it recently because his garage had become too small as a studio. As we made our way towards it, our conversation turned to construction. Ferretti expressed his preference for stone as a building material - a superior building material as he put it - but not so accessible here. In Italy, of course, there were the hill towns, all built of stone. It wasn't just that the stone was available there, he told me, but "look at how long the buildings have lasted." And the stone was not expensive. In any case, concrete was perhaps as good. The advantages were similar, he explained.

I recalled a trip to Italy, and being much taken by the old hilltop towns and their buildings, all of stone, and so enduringly beautiful - as anyone who has visited Italy knows. At the same time, the many ways Paolo Soleri used concrete in his buildings in the Arizona desert came to mind.

It was broken concrete from the demolition of a city sidewalk that Mr. Ferretti had used for his piece of public art "The Cove" which he designed and built for the town of Albany, California.

The Cove, part 1

When I'd first seen a photo of The Cove I was struck by a quality I'm not used to seeing in a work of public art. It had none of that generic quality which says "This is contemporary art." To my question, "How did his project come to pass?" Ferretti began a long story.

One day in April of 1998 Ferretti's daughter brought him a copy of the local weekly. It contained an announcement for "a waterfront, public art project"-- the City of Albany's first. Proposals were due in two and a half weeks. Total money available for the project: $10,000.00.

Ferretti had an impulse to respond. "What could I lose?" he said.

"So tell me about it," I urged him.

"I worked frantically to understand what would be reasonable and appropriate. A few days short of the deadline, I found the solution and drew it up in two 24 x 36 inch drawings," he said. A month later, Ferretti got a letter of congratulation, along with a contract. Excited to have won the competition, he went down to the city hall with the signed contract. At the desk he was informed a second artist had also been commissioned to do a piece.

"Hearing this, I felt uneasy," he told me. And as he was handing over the contract, the clerk said, "We all wonder how you're going to do this."

The Dysthymia of Public Art

Over the past few years a number of artists have described their experiences to me of doing public art projects. The descriptions I've heard cover a spectrum from the frustrating to the absurd. One artist, Ursula Von Rydingsvard, told me how she was forced to use union labor and how the men resented being told what to do by a woman. Besides that, they regarded the art work itself with ill-disguised contempt. Hers was a tale of the workers' sabotage and passive aggression towards her, and of the delays and cost over-runs that resulted. That the work was finally completed is a testament to the artist's fortitude and will. Another artist told me of endless committee meetings and red-tape, unforeseen reversals stemming from city politics, time and energy spent on efforts of persuasion and of multiple-year delays. Most substantial public art projects, he has come to realize, are five to ten year propositions.

Besides the delays, the reversals and added expenses, apparently other problems are not unusual. A variety of insults can befall a public work once it's finished. One artist told me one of his large sculptures was repainted without his knowledge -- "ruined" was the word he used. Pieces get moved without the artists' notice or consent and, of course, removed from public view. And demands are sometimes made for the artist to repair damages without compensation. I heard one case of an artist who had not even received the small amount of money due her, being asked to repair, at her own expense, damage done by vandals.

The Cove, part two

The Cove was Ferretti's first public art project. Apparently there were provisions in the contract that had escaped him. Upon asking when he could begin work, a city official told him all that would be required was a copy of his contractor's license and proof he carried suitable liability and workers compensation insurance. Ferretti had none of these. Looking into the insurance he found it cost about $4,500.00. He also discovered he would not be able to use materials existing on site. "It was not what I was told, originally." he said. And besides that, he told me, the contract called for additional drawings. "Why?" he asked me rhetorically, his eyebrows raised.

The drawings took him another month to complete--a month, he explained, because he took the time to work out some design refinements and, as he put it, "I needed time to understand what had taken place inside myself."

Ferretti delivered the new drawings to the city along with a cost estimate, and began looking for a contractor, one with suitable insurance who was willing to take on the project for $10,000.00. "It wasn't much money for what needed to be done," he explained. And where was he going to get the materials? As Ferretti put it, "It was around this time that I started praying to my mother to help me."

Not long afterwards, Ferretti noticed that the city was replacing some of its sidewalks. There was a lot of broken concrete which would be perfect for The Cove. Ferretti made inquiry to the Director of Community Development to see if the broken concrete could be saved for recycling in his project. Yes, certainly. And so at least one difficulty appeared to be surmounted. About the same time, an announcement about the two projects had appeared in the local paper. The writer mentioned that Ferretti was looking for volunteers. A group of young builders had responded enthusiastically. "I thought I had found my helpers," he said. It was an auspicious beginning, after all.

Feeling relaxed now, Ferretti allowed himself to take a planned trip to Italy to visit his father. When he returned a letter awaited him from the Director of Community Development. The director was leaving his job, but assured Ferretti that all would be well as he had discussed the project with the Coastal Conservancy which would have to approve the form and content of the piece, anyway.

"But wasn't it already approved?" Ferritti asked.

Meanwhile, the broken concrete from the sidewalks had disappeared. And it also turned out that the builders who wanted to embark on Ferretti's project did not have the required insurance. To their dismay, as Ferretti told me, he had to cancel their heartfelt effort to help him.

After several months and much effort, Mr. Ferretti was now back at zero. He began visiting lumberyard and building materials vendors trying to find someone who might take an interest in his project. Responses were positive and small donations of equipment were offered, but nothing substantial materialized. One day Ferretti noticed the demolition of a concrete building underway. Would the contractor consider delivering the broken concrete to his waterfront site.

"Sure," responded the contractor, since it would save him time and money. "But you have to let me know within an hour." The city refused to grant permission, however, because Ferretti did not have the required liability insurance.

About the middle of September, Ferretti found a contractor who had been an art student when younger. His backhoe driver was a sculptor. It looked promising. A meeting with the city was encouraging. However, the city now wanted more drawings. They wanted the exact location of the project.

"But I'd asked the city for an accurate map of the site and they had never given me one." Ferretti explained.

So he and his wife Barbara went to the site and laid stones out to mark the perimeter. They planted stakes and tied yellow tape to mark off the area, and while working on the site, a man identifying himself as "The Preacher" came up. When he learning that a sculpture was being planned, he became irate, and warned Ferretti that he would tear down any idol that would be erected on that spot. Ferretti smiled wanly. On the other hand, he told me, others stopped to talk and were more encouraging.

Ferretti delivered the new drawings to the city and, on the 25th of September, received an encouraging letter from the city delineating, in seven bullet points, what would be required of the contractor. Meanwhile. the contractor and former art student was no was longer returning Ferretti's phone calls.

Fortunately, in short order another contractor was found who was interested in doing the work. But it turned out he lacked the required level of liability coverage. At this point only three months remained on Ferretti's contract. The work had to be completed by the end of the year and had not yet even begun. A viable contractor had not been found, nor had a source of materials been located. Ferretti was exhausted, and was having trouble sleeping.

A few days later, in conversations with two artist friends, unexpectedly, mention was made of an art student they knew who was working as a contractor, an Italian from Canada who lived in the Bay Area. Ferretti called him immediately. He was interested. "But there's only $10,000.00 available for this," Ferretti told him. Gino replied that it would be "a nice diversion from his other jobs." Moreover, Gino had a license and the necessary insurance!

Ferretti turned the project over to Gino and a new contract with the city of Albany was drawn up, superseding Ferretti's contract. And the problem of finding the broken concrete remained.

The morning of November 12 Ferretti's wife burst into his studio telling him that the brand new sidewalks that had been recently poured on Solano Avenue were being demolished. There'd been a problem with the concrete mix. The contractor doing the demolition, it turned out, would be happy to deliver the broken concrete to the site. And this time, the city approved.

As Ferretti tells it, a crew of four, sometimes five men, from El Salvador, which included a master mason, worked on the project. By February of 1999 all the concrete was in place. Ferretti noticed that a single piece, oddly enough in the very center of the floor of the construction, had somehow not been cemented in place. Mixing a little mortar Ferretti set this last piece himself.

The Cove was nearly complete. All that would be needed, Ferretti felt, would be two or three more truck loads of earth to bring the banking around the sides to just the right levels. But the money was gone and the city would not provide the additional funds.

As Ferretti and I walked around The Cove four years later he told me, "The Cove never really had a title. Finally I made one up. It doesn't have my name on it, either."

Leading me over to the other project the city had approved, I found myself looking at a corporate-style sculpture of two large birds. Mr. Ferretti pointed to the name plate showing the artist's name and title of the piece.

"I thought about putting one of those on name plates my piece, but it reminded me of a cemetery. I just couldn't do it."

Carlo Ferretti got no money for all his work, nor did he end up with his name on his own creation. In fact, as he told me, on the day of the official dedication, "There were men in suits, and people spoke into a microphone. I was there in a little crowd of people, and I watched. But no one ever noticed me or mentioned my name."

During the telling of this entire story, which I heard on my first visit to Mr. Ferritti's home, he never once raised his voice, nor did he betray any bitterness. It was a story told with a philosophical attitude, although not without its justifiable share of quiet irony. Along with much that strikes me as extraordinary in this story, and beyond the visual poetry of work of art itself, this has remained with me as the most remarkable aspect of all.

In a note Ferretti sent me afterwards he wrote that, "In the end, I was able to obtain almost everything I strive for; respect for the site and the materials, simplicity, strength, dignity, anonymity, the primitive, the commonplace, the vernacular, the obvious, the unnoticeable, the apparently useful, the unfashionable and, most of all, the creation of a presence by omission."

About the Author

Richard Whittaker is the founding editor of works & conversations and West Coast editor of Parabola magazine

SUBSCRIBE NOW

TO OUR MONTHLY NEWSLETTER

Share Your Comments and Reflections on this Conversation:

On Aug 29, 2020 Maria wrote:

Richard,I loved your piece! I’m a regular dog walker and avid plein air painter in this area. I’m in love with the Albany Bulb and appreciate learning about Mr. Ferretti and tribulations in this narrative. I want to include the Cove in my Bulb Series to honor Mr. F. And will pass this link to all my friends. Thank you for all the details about the man and his work! Is there a plaque with his name now?

On Jun 11, 2014 Michael Wallace wrote:

Mr. Ferretti's work and spirit tells us who he is. The hurdles placed before him by a mindless ego driven bureaucracy tells us why our country fuctions so poorly. A cultures art and creativity is it's highest expression.