Interviewsand Articles

A Conversation with Pat Benincasa:A Geometry of the Heart

A Conversation with Pat Benincasa:A Geometry of the Heart

by Richard Whittaker, Pavi Mehta, Feb 17, 2020

Pavi Mehta brought artist Pat Benincasa to my attention. She suggested we have a conversation, the three of us. Then she told me a stunning back story, I looked at Benincasa's work on her website and that settled it. The following conversation took place on February 17, 2020. It will appear in works & conversations #38. - Richard Whittaker

works: At the age of 16, you’d been drinking and went out and laid down at night in the middle of a busy street. I mean you could have died there.

Pat Benincasa: Yes. I was a teenager, drunk—feeling all these things and acting out.

works: But then a voice came through to you. Would you say again what happened?

Pat: I remember sitting on this road and I heard it in my head, “Do you want to be a drunk or do you want to be an artist?” Even at that moment, it stopped me cold. Whether I was drunk or not, there was an electric connection to that thought that put everything into context.

works: That’s an experience from some other level, right?

Pat: Absolutely. Boy, are we going to go down this road?

works: Well, we could.

Pat: It’s a connection. I never saw being an artist as anything other than a calling. When people talk about careers, that just never computed. Like, “What the hell are they talking about? Careers?” This is a calling. This is why God made me, to be an artist. That’s all. I mean, I just knew that. No one told me. My family never talked about art. I’m a first generation American. My relatives spoke broken English, worked in the factories, or had small businesses. My parents were more Americanized and they had a business.

works: What part of Italy did they come from?

Pat: Calabria, Southern Italy. The Calabrese are known as the testa dura, the hard heads; they’re known for their stubbornness. All this is to say, I really don’t think we ever do anything by ourselves. I believe we carry our ancestors with us. I truly believe that, and maybe they were looking out for me that time.

works: Well, even to hear you say that we carry our ancestors with us—this is an interesting thing, but not part of the world I grew up with here in the U.S.

Pat: Okay. Now, Richard, I was born in the United States. Okay? But when I went to my American friends’ houses for dinner, I’d think, “My God, these Americans eat funny.” Then I’d say to myself, but I am an American. I always felt I was in two worlds. So, the idea of honoring ancestors—and the Romans did it—when you walked into a Roman house, they had busts of their ancestors. I mean that’s in the bloodline.

works: That’s sort of a big thing, and we could go further into it, but let’s go back to the voice you heard that night in the middle of the street. Was that something you were used to, hearing voices like that?

Pat: No. If anything, Richard, if I got a hit like that, I’d argue with it or put it out of my mind.

works: I mean, I listened to the talk you gave at Perpich, the arts high school near Minneaapolis. You said, “Even as I tell this story, I can hear that voice; it’s right here with me.”

Pat: As if it happened this morning.

works: To me, that’s evidence of another level that’s part of us. Maybe most of us never have an experience like you’re describing.

Pat: I don’t know. Do most of us listen? I spent half my life trying not to listen.

works: Well, given the description you gave of your experiences in high school, it would be understandable. You said it was 12 years of humiliation, shame and ridicule.

Pat: Yes, yes, yes.

works: Where do you think you got the strength not to be completely defeated by that?

Pat: In those days, in parochial school, you had to go to mass every day. It never occurred to me to associate what was going on in school—it seems like I put things in little baskets in my head. So, when I’d go to mass and see all these statues of saints, they weren’t plaster clichés to me; they were people just frozen, standing there. And of course, you have to learn their stories. And I got a double-whammy; I’m an Italian American, so I’m a walking index of the saints. Okay? And when I studied them, I kept gravitating towards those badass saints, the ones like Teresa of Avila, Catherine of Siena, and a guy that wants to be a fool for God—Francis.

I’m looking at these people and geez, I would study them. I would talk to them. I didn’t intellectualize it, but I knew I could fortify myself with them, and I don’t mean in a religious way. I wasn’t a particularly religious kid—well, yeah, I kind of was back then—but I talked to them. They somehow were real to me. These are people that would let nothing ever stop them, nothing. Nothing. And as I got older, I started putting in my basket of saints, writers, poets and artists. That’s a pantheon of sheroes and heroes that have carried me.

works: “Sheroes”? That’s a great term. [laughs]

Pat: Sheroes and heroes. You bet! I think I was fortified by them.

works: That’s a good thing. I can’t help but think it’s the real stuff.

Pat: Yes. May I add another piece to this?

works: Please.

Pat: Okay. So, I’m like 12 years old, and I’m from the Pontiac area near Detroit. So, I walked to the Pontiac Mall and go into Dayton Hudson’s. They had a little bookstore up there. I’m full of my badass self, because I’m 12, 13, and I walk up there with money in my pocket. So, I went into this bookstore and found it—like the Holy frickin’ Grail!—there was a book of paintings. I’d never seen anything like it!

I pulled it off the shelf and opened it to Giotto. The tenderness in those paintings, the expression—those Giotto trees and the mountain terrain—it was like I was looking at a family album! That’s what it felt like.

And as I flipped the pages, there’s Piero della Francesca! I saw this painting, The Flagellation of Christ. It was so still, Richard. The subject matter is violent, but there’s a stillness that was profound, and I wanted that stillness in my work. I don’t even know what else to say.

So, that was pivotal. I bought the book and think I wore the pages out—this is what painting and art is? Then they became saints. What’s the difference between Francis of Assisi and Giotto’s painting Francis of Assisi? To me, they’re one in the same.

works: I love that story! You said that in high school, “All I could do was draw.” [yes] It was a refuge for you.

Pat: Always, yes.

works: What did you draw when you were younger, like a fifth or sixth-grader?

Pat: Anything! I would draw trees. I would draw saints. I would draw objects on the table. If I was at a sporting event or something, I’d start drawing, or if I was sitting in the back of the car, I’d start drawing the back of somebody’s head. Who the hell knows?

It’s just that no one could take that away from me. They couldn’t make fun of it. They couldn’t drag me up to the front of the room to humiliate me. It was my world and I really believe art saved my life. I do. That’s why I can recognize it in kids. When they walk in that door, Jesus, I can read them, energetically. I feel that energy. So, yeah.

I’ve been doing a lot of writing lately. I was trying to prepare for this interview because I was nervous, and I wrote: your art is the place you always return to. It’s the place without borders, time, or expectation. It is a geography of longing that maps its own meaning.

works: That’s really beautiful.

Pat: That’s the truth of it.

works: What are you doing nowadays? I mean, you have a teaching position; you’re working full-time in your studio—just give us a little sketch.

Pat: Okay. I’m not teaching. I stopped teaching this year.

works: Where were you teaching?

Pat: Perpich. I left because I was asked to design a visual arts program for a new arts high school in Eden Prairie, Minnesota. It was the Main Street School for Performing Arts. They bought a building and said, “Come and design a visual arts program for us.”

works: Would you say something about Perpich?

Pat: Perpich is a nationally recognized arts high school in Minnesota. Governor Perpich built it after he saw the movie, Fame. It has poetry, literature, music, dance, visual arts, media arts—it’s a phenomenal school.

works: It sounds fantastic. And so you were just invited to design a visual arts program?

Pat: Yeah, for the Performing Institute of Minnesota Arts High School. They call it PIM. Two years ago I went there. We started with 12 kids and as of this year, when I left, they had 90. We went from one teacher to three, so I knew I could leave it, Richard. I also knew it was time for me to stop full-time teaching. I think there are other things I need to do now.

Pavi Mehta: Can I jump in? And this is going to be a back and forth, in all directions. But one of the pieces I was so intrigued by from your story, is how you found your own teachers, and they were outside the system. You carved your own path and then re-entered the system.

Pat: Yeah.

Pavi: That, for me, was one of the most powerful images of your talk. How did you carve that path out for yourself? I’d love to hear more about.

Pat: Well, I got into teaching by mistake, as you know. I talked about it when I was invited to teach at the Minneapolis College of Arts and Design. I didn’t know why they were calling me and, after refusing at first, I did agree to teach. That was my first walk back into teaching. I knew everything that I did not, and would not ever, do to a student; therefore, there was my handbook, Pavi! How to teach. It was right there!

So, I just did it, and I liked it. I loved watching these kids open up and blossom. Some of these kids—with their outrageous posturing and questions, and this wonderful vitality—I thought, “Wow, this is awesome!”

Then, later on in my life, I was getting a divorce. Up until then, I was doing freelance work. My daughter was about two years old, and I couldn’t keep doing that. I needed solidity. I was a tour guide at the state capitol and you work with kids, and someone said, “Where do you teach?”

I said, “I don’t teach anywhere.”

And they said, “Come on, you must teach!”

I kept getting that response and I thought, “What’s wrong with these people? Remember, Richard, I told you I don’t always get the picture when the universe is tapping me on the shoulder.

But finally, I did listen. I went back in ’92 and got a K through 12 certificate. I researched all the school districts to avoid and found one in Roseville, Minnesota. The art department was built like a college art program. I met the two guys teaching there and it was love. They hired me. I became department chair. I was there almost ten years.

That was the beginning, and God, I loved it! I loved being in the classroom because it was a studio, not a classroom. If I thought of it as a classroom, I’d be paralyzed. And all these kids—whoa! That’s the alchemy right there.

works: Well, I think you were a gift to your students. Would you say something about how you think about the people who become artists? What is it about those people who move in this direction?

Pat: Boy, that’s a huge question.

works: Yeah, I know.

Pat: But you do that. I read your magazines, Richard, I get your questioning. In fact, I liked one of your interviews so much that I emailed Ann Weber, the sculptor. I was just so taken by her interview—and she answered me right back—kindred spirits.

I tell the kids I’m ADD and can go off on a tangent; it’s called “going in the ADD car.” So, it’s time to park the car and come back to your question.

works: No, no. I like the ADD thing. That’s interesting. Ann Weber is an inspiration. You must have really felt you connected with her.

Pat: I did, I did. Her work is phenomenal—but that interview is so down-to-earth and refreshing and raw, and direct. I loved it.

works: And she’s a Minnesota person.

Pat: I found that out. Her mother lives 15 minutes away from me! But you asked, what’s that thing that’s so recognizable in these kids, or in creative people? I think it has something to do with the profound need to connect. These kids come in very young and there’s this need in them to tell a story.

Artists are storytellers; that’s what we do. That’s how we know each other. I can see an art kid coming into the building; I can spot them a mile away. It’s almost like it’s tattooed on their forehead. But it’s like I read it on an energetic level. I feel it. You know it when you’re around artists.

works: Yes. I don’t mean to go off on a tangent, but a lot of the gatekeepers in the art world—often they’re not these kinds of people.

Pat: Oh, Richard, we’re not going to go down that road. I want to keep my language nice. But let’s go around it to the back door.

works: All right.

Pat: I caution kids that when people start talking to you about the “phenomenological approach” to the artist’s intent, run like hell! You can do the smart talk and speak artese, or you can be yourself. Take a chance on yourself; be yourself in your work.

I don’t really feel part of this art world. I just feel like I’m doing my thing. I find like-minded people. If I can touch lives, and if my life is touched,—to me that’s the art world, the one I care about.

works: Well, thank you. You know, that’s poetic. Like a phrase from your talk at Perpich: “When you come down the cosmic baby chute.” That’s maybe the best phrase I’ve heard for birth—bringing in the cosmic part.

Pat: It is cosmic.

works: But usually, when we talk about “cosmic,” it’s intellectual. We’re in our heads.

Pat: Well, are you talking like an American?

works: You tell me.

Pat: I don’t know. When you think about so many Americans—we worship logic. We love that linear yes/no. And the second you put in things that are not logical—like listening to your ancestors, or being guided by unseen things and paying attention to them—someone thinks they just turned on “The Twilight Zone.” But it isn’t. I think there’s a much bigger connectivity out there. All right, case in point. Growing up, we were told “universe.” Well, what the hell is a universe? Now they’re talking multiverse! Now, do I want to be a “multiverse” or do I want to be a uni-verse? That’s what this is about.

works: That’s good, Pat. What I like about the “cosmic baby chute” is that it opens a little door into the fact that we live in a mysterious world. Someone I talked with recently [Rachel Naomi Remen] has this great phrase. She said, “We’ve traded mystery for mastery.”

Pat: I agree with that. May I digress?

works: Please.

Pat: Okay. We’re in the ADD car now. Fasten your seatbelt. When I moved to Minnesota, I had an MFA and MA in drawing. I thought I was going to draw the rest of my life, because when you’re young, you think once you learn one thing, that’s what you’re going to do—which is not true. So, in Minnesota there are all these places of worship: the Boundary Waters, you have to go to Orchestra Hall—there’s a whole list.

I went to Orchestra Hall and I was listening to this Mozart piece, and I felt this profound kind of rage and longing and anger building up. Then I heard myself say, “Oh, my God, a musician can fill a space, and all I can do is describe it.”

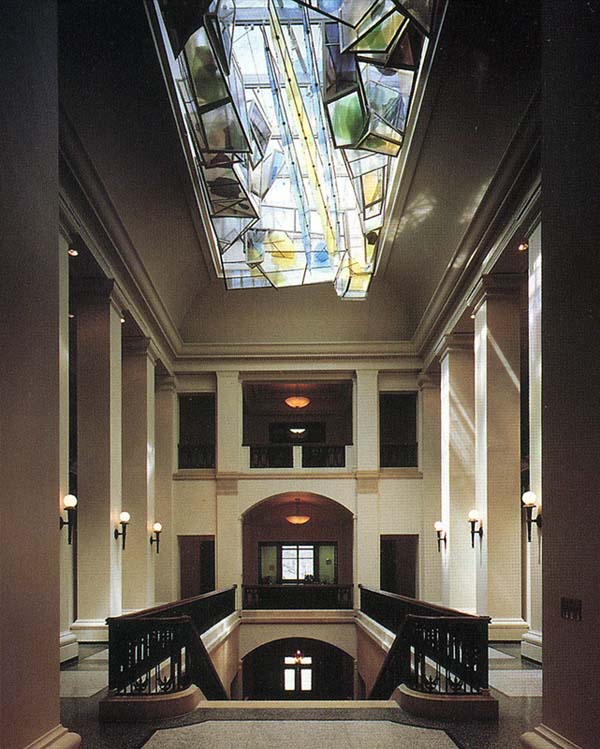

It knocked the wind right out of me; it broke my heart, and I thought, “What the hell is that?” I didn’t know what it meant until years later, when I started working in glass and steel. I built a seven-ton glass and steel skylight at the Minnesota Judicial Center.

One of the things about glass I love is that it’s pure contradiction; it’s empty and full, simultaneously. So, with a room of glass, if I said, “Richard, hand me that reflection,” well, you can’t. The room is empty and full; it’s full of this richness of color and refracted light. It’s a contradiction, and I love that. I realized it was the contradictions that I love—that mystery. Although, I’ve got to tell you quite honestly, I’m really a chicken shit, and I hate things I don’t understand. Okay? I’m a fraidy-cat. l can have this dialog with myself: “Why are you going towards it? What’s the matter with you? Back up, back up.” And then I go towards it.

works: What you’re saying just reminds me of how you haven’t let your fears stop you.

Pat: I don’t know how that’s happening, but yeah, I try not to.

works: People could take hope from that. It’s hard not to obey your fears, and yet, if we obey all our fears, we’re trapped. We already have enough trouble without obeying all our fears. It’s good to talk to someone who’s sincere and will admit, “Okay, yeah, I’m a fraidy-cat.”

Pat: Oh, God, am I ever. But I don’t want to mislead anybody. I don’t think bravery is like, “Yes, I’m going to do it.” I think when we have to do something and we know we’re scared to death to do it… I take it back to my ancestors. There’s a strength bigger than me that guides me. Sometimes, when I’m scared shitless, excuse me—I’m really watching my mouth. Okay?

works: Don’t worry on my account.

Pat: So, when I get really frightened about something I’m about to do, I say this phrase over and over to myself. “I am guided. I am loved. It will be okay.” I just repeat that over and over, because I know it’s not coming from me. So, okay. We’re going to park this car and go into another one real quick. I do yoga every morning. But I despise exercise. Let’s just be upfront about that.

So, I do yoga—it’s from a DVD—and the woman at the ends says shavasana [corpse pose] “surrender and lay your bones,”—and I get into it. Well, one day, she said, “Release yourself into the ground,” and I saw was I was releasing myself into the hands of my ancestors as they were crowd-surfing me into my day. I’ve never forgotten that. So, when I do morning yoga now and I release myself, I say, “I release myself to my beloved ancestors. Crowd-surf me into the day.”

works: That’s priceless. So tell us something about your parents? I’m sure you got something from them.

Pat: Not just my parents. My dad came to this country, and came from bitter poverty. I went back to their family village when I was in college (both parents came from the same village) and I met my relatives. It was poverty.

You know, Richard, I think about this a lot, with all this talk about immigration. I still think like an immigrant, even though I’m not. My mom and dad came to this country. Their families knew each other in Italy, and they weren’t too choked up about each other. My mother thought my dad was arrogant, and he was.

They started businesses together; then my dad ended up as a bank board member. He was an entrepreneurial businessperson. They were both embarrassed that they only had a high school educations, but they read all the time. My dad’s attitude was, it’s never a question of if, it’s always a matter of how. And I had a double-whammy because growing up in the 50s, 60s in an Italian household and milieu, the boys were king babies—everything revolved around them.

But because I was female I was allowed to pursue this art thing. Now, my parents believed in college for girls. Half my cousins didn’t. If I’d been a boy, my father never would have let me do this art thing; it would have been business. But when I was around ten, I’d come down and we’d have coffee Sunday morning. He’d say things like, “You know how you can see who’s going to give you trouble in a board meeting?” I’m ten years old, “No, Dad. How?”

He said, “You scan the room—you have to know in two seconds—and it will always be the son-of-a-bitch with the beard and the sincere look on his face. Look out.”

He gave me some other tips and I’ve held onto them. I’ve done these major public art projects. I walk into a room and honest to God, Richard, I can feel “incoming.” He raised me to do that, but with a mixed message: “It’s a waste that you’re a girl, but here, I want to tell you.” It was really crazy making.

But my grandmother, Raffaela, is the one I really looked up to—four foot-eleven, the bluest eyes, the biggest heart. This woman was formidable. Now, the grandmothers didn’t learn English, maybe ”ice-a-box.” They taught my cousins Italian, but Raffaela did not teach me Italian. I always wondered about that; then I realized why. She taught me the language of the heart. Raffaela had four children. Her husband came to the United States and was building sewer lines between Pontiac and Detroit. She was raising four kids by herself in this impoverished village. And she was the most joyful person. That was a choice she made and I’ll never forget that. Nothing stopped her, and people always went to her. I carry her with me every day.

works: That’s really a wonderful story. Okay. Here’s a good one. I love this line from your talk at Perpich. You said, we are but shadows in the smoke. I mean, I don’t mean to embarrass you, but you’re a poet, too. So tell us about this, that we are but shadows in the smoke.

Pat: That’s what we are. Everything around us is illusion, everything we do. I can meet somebody and try to script how they should act or what they should say, I create these illusions. Okay? Or I go into the world with expectations and dreams, and things present themselves. We are but shadows in the smoke, it’s all just pure illusion.

works: That’s what they say in Hinduism, that we live in maya, illusion. But we don’t believe that. Right?

Pat: We’re going back to that American thing, Richard.

works: [laughs] Well, I’m kind of stuck there. My family’s been here a long time.

Pat: I’m sure. But you asked me a question I didn’t answer like what I was doing now.

works: Right.

Pat: I chose to stop teaching full-time. I think I wrote to you, Pavi, that I wanted to jump into the nothing to find the something. And can I do this? It took me months to think about leaving teaching. But it’s like it was in art school—you measure yourself by what you produce. You have to be making, making, making.

I built a studio in my backyard, so I commute ten feet. Since leaving teaching, I started a YouTube series called PatChats. They’re for artists. I just finished one called: PatChat: Making Art In Stressful Times. I’m doing them, because I still have to do teaching—and I do talks. But what’s really scaring me is that I’m not in my studio making. I’m writing, and there’s this battle going on in my head, “What the hell are you doing? You’ve got to get back to your work in the studio.” Then it dawned on me—what if it’s about writing?

So then, a former student—a brilliant artist—emailed me. She saw my first PatChat and wrote to me, “Oh, my God! I can’t believe your timing. I’m going back to my work, I’m finally carving out time for myself.”

I sat with that for a couple of days and then wrote back to her saying that in art school, they drill into us that if you’re not producing, either you’re lazy, you’re a hobby artist or you’re not worth anything.

I said, “But now that I’m thinking about it, I’m coming to believe that’s not an accurate portrayal of a creative life.” Creativity can be about her raising her babies, helping her husband with his business, or touching lives, making a difference—and being.

Who’s to say that art school defines what’s creative? I’m getting pissed by that, because what is creativity? It spills into other buckets, it doesn’t stay in one.

works: This is should really be underlined. There’s someone here in the Bay Area, Ann Hatch, who is all about getting this message out, that creativity belongs in every part of life. A simple example is a dinner party. There’s all kinds of room for creativity there. Ann created the Oxbow School, with Robert Mondavi. It’s a regular college prep high school except that all the courses are taught by artists. So you and Ann Hatch are on the same page here—and Joseph Beuys, too.

Pat: Well, also, going back to the art world, when you have art professors who are bringing in triple-figure incomes, telling kids, “You have to live off of your art,” that’s huge. They have a comfortable life, and young people buy that stuff—that there’s only a certain way of making and selling art, or you’re of no value.

works: That’s rough.

Pat: It is. One of the things I’ve always told kids is when you go into art, what other things are you good at? Do you have a foreign language? Do you cook? Whatever you do, cultivate those things, so that when you flow in and out of your art making, it doesn’t become this binary of making art/not making art. You put a roof over your head. You pay your bills. It’s not an either/or.

works: You said something earlier—and I think it relates to what we’re talking about—you spoke about following something invisible, the importance of doing that.

Pat: Yeah.

works: That’s a big thing. That certainly jumps out of any category that you might want to name—like I’m an artist, I’m a lawyer, I’m a mechanic. And you quoted Heidegger, I think.

Pat: Yes. When Heidegger asks: What is a thing? His answer was “you know what a thing is by the way it gathers the world unto itself.” It gave me a way to understand art: you know what art is by the way it gathers the world unto itself. Art is a point of proximity that dissolves the distinction between our “here” and “there” as it pulls us toward each other.

works: Wow. That kind of bowls me over, Pat. So how did you connect with Heidegger?

Pat: Okay. When I left graduate school—I spoke about it in my talk—I moved out here to Minnesota, and I was meeting all these brilliant artists, and they were talking about things. So, everytime I was out with these people, I’d go to the bathroom and write down all the books they talked about, all the poets, the writers—whoever they were, I wanted to know. I was a reading fool. And one thing leads to another. French literature turned into Russian, Dostoevsky—and then you go into theology, philosophy. It was a lovefest. I couldn’t get enough. Then I came across this writing of Heidegger’s and it gave me such an understanding of how to put into words what art is.

My other way of saying what art is—when kids would ask, I’d say, “It’s when you stand in front of a painting, and you don’t even know where your here begins or where there starts.” Or when you hear a piece of music, it’s so purely one thing. That’s the invisible, that’s the power.

works: That’s beautiful. There’s a whole conversation there, but my hat’s off to you for getting through art school. I don’t think I could have. But I love talking with artists. My feeling is that people who want to be artists have an unspoken longing for a real life, a life of their own. It reminds me of when you said that creative people are always looking for meaning. So, what is it that gives meaning? You relate to this question, I know.

Pat: I do relate to it, because there’s something that drives us. There’s almost like this gossamer thread—and I say gossamer because it’s so fragile in some ways. Whether you go to art school and they make up this hierarchy of achievement you’re supposed to buy into, or how you live, or how many shows you have, and what gallery is carrying you? what museum are you in?—this thread is the only thing that matters.

But most of us go through art school and we don’t live like that. And here’s the odd thing about what you’re saying. You’re right, artists look for meaning. But artists are very sensitive—God, we take it on the chin. We feel everything. That’s not to say other people don’t. I’m not trying to suggest that. So, what’s the one field we go into? The one about rejection. Now, when you think about it, what the hell is that? I mean, this need for meaning is so compelling that I’ll put myself out there; I will tell my story about being drunk in the road—or put out my industrial paintings, or whatever, to this public at-large, come what may. That need to connect, and that hunger to touch another life—based on what you’re putting out there—is more compelling than having the fear of saying I can’t do this. I’m going to live some meaningless life. It’s a hunger. A magnificent compulsion, a state of grace. It’s a state of grace.

works: Well, that’s lovely. Pavi, do you want to say anything here?

Pavi Mehta: There’s so much. Two things I’m curious about, Pat. One is when you talked about, we’re shadows in the smoke and the illusion, what is it in this culture? Even the word “disillusionment” is seen as a negative thing, whereas it seems like you found your freedom in that. Can you speak a little bit to your relationship with just being able to see things as an illusion? What is it that buoys you within that?

Pat: I think I came to it, Pavi, the hard way. In the first half of my life, I never met an illusion I didn’t buy into. Okay? I think I felt so intellectually inferior to people because of my education that I became Fifi the performing poodle, jumping through hoops of approval. I was married very young, because that’s what Italian women did, and the sun and the moon were supposed to rise above your husband. Well, after 17 years of marriage, it didn’t work that way—and that’s all I can say about that.

That was the beginning of my awakening, if you will. If you haven’t figured this out, I’m really emotional, okay? I get excited. Now, as I’m older, when I feel that first “Oh, boy!” I walk myself back and say, “Now, what really is this? What am I feeling?”

So, maybe it’s that element of being more reflective. Then, it’s almost like I can shatter the illusion—and then the beauty of what is, is there. The illusion is just that: I can’t see it. If I’m willing to take the risk, shatter the illusion, then it’s revealed. Whatever has to come forward will be revealed and that requires a certain kind of trust. It goes back to “I am guided, I am loved, it will be okay.” I really feel like my ancestors are guiding me. My beloved ancestors are with me all the time.

I once gave a talk a couple of years ago to students at PIM about a letter I wrote from my 67-year-old self to my 17-year-old self. I wrote: “You got me in trouble; you were shooting off your mouth. You were running after things. You were so emotional. You got hauled in. You got suspended. I thank you for every one of those things.”

Then I talked about the flipside of what those things did to make me the woman I am today. I couldn’t have done that without that badass 15-year-old with the attitude and the mouth. I was rageful about my education and had that chip on my shoulder for many years.

It wasn’t until I started letting the illusions fall away that I realized the universe had given me a precious gift. Those formative education years couldn’t have given a better preparation to be a teacher! That was the guidebook. But I didn’t look at it that way when I was younger. I had a chip on my shoulder the size of frickin’ Nebraska about that.

works: It reminds me of how sometimes, in the middle of a creative effort, an idea comes up. And one part says, no way, but then this other thing appears and says, “well, why not?” I think that attitude—and the energy it has—is really based in anger, like you’re saying.

Pat: Yes. You’re so right. Again, that rage and anger was a gift, because I made art out of it. I made art out of being told “no, this work isn’t going to… “you can’t do glass because it’s craft.”

I remember being told, “You can’t use glass; nobody’s going to take you seriously.” My reaction was—I won’t say it out loud.

Artists follow the idea—that’s what we do. If the Universe gives us that damn idea, we will follow it. So, for me to stop painting and to go into glass—that’s what I did! But that was out of rage and a FU attitude: I’ll show you, I’ve got work to do here.

works: Well, I recognize that.

Pat: Yeah. Simpatico. I’m not going to use an American word for that Richard, come on.

works: No. I never would have started the magazine if it hadn’t been for that. I admit I was terrified when I began, but it was out of something you recognize. I’d get so pissed off at stuff I would read, really angry.

Pat: Well, when Pavi sent me your magazines [works & conversations], I have to say, I thought, “Okay. Art world, what the hell is this going to be?” I’m sorry, but you know, “1-800-MOREBULLSHIT.”

works: Oh, yeah [laughs].

Pat: When I got the magazines I looked at the nature, of your questioning, and I thought, “What is this? This can’t be.” So, I read one article, then the next one; then I read through one magazine, and then another. I read the introduction, when you talk about the content, and I read the cartoons at the end. I’m looking at this and I thought, “My God! This is real.” I mean, you’re talking about art, but it’s real. I’m speechless, because it’s not like the major art magazines; it’s not that kind of talk.

You got into the heart of the artist, the eyes of the artist, the vision of the artist, and you did it lovingly. You bring out stories in people. That’s what that magazine is about. I went running down to my partner and said, “My God, this is an art guy that’s real!” That’s all I’m going to say about that.

works: You’re making me feel pretty good, Pat!

Pat: You know, Richard, now, more than ever, now, at this moment in time, what is authentic, what is truthful, what is of the heart, truly has a profound effect. What you’re doing—you’re a guerilla art maker—you talk about this work. To me, we’re in the trenches, getting as much goodness and authenticity, and things that are meaningful out there as much as we can.

works: Yes. I feel that, too. Now I have to say that I like your art very much. And I don’t know where to dig in, but at some point, I want to ask you about the Redemption Window.

Pat: Yes. That was at Hill-Murray School. They wanted to hire me as an art teacher. In the interview I said, “Are you kidding me? Art and parochial school? I wouldn’t teach at a parochial school, but I’ll be an artist-in-residence.” I heard it come out of my mouth, Richard. I do this all the time; these words come out, and inside my head I’m going, “What are you even talking about?” But I’m artist enough to follow the train of thought, you know? Again, it’s my ancestors. They gave this to me, and I grow into it. I trust that.

works: Beautiful.

Pat: So, I created a visual arts program for them. In fact, I’m designing a visual arts program for another school in St. Paul right now. It seems like I can make a supplemental income doing that because I know how to do this. Anyway, so when they built this beautiful chapel, Joe, the president of the school said to me, “We’re going to build a steel cross outside the window to let people know it’s a chapel.”

Now, Joe knows me for about a year, and I looked at him and said, “Joe, what the hell are you talking about? A steel cross in front of a chapel window? No, no, no. You need a three-dimensional glass and steel crucifix out of cut-glass, perched on limestone boulders.”

And he said, “Oh, well, show me.”

I said, “Okay,” and left. I came back to my studio and thought, “What am I even talking about?” Well, I did 3D sketches with a hot glue gun. I built a model of an 11-foot glass crucifix perched on limestone boulders—the rock steps of Golgotha—and I built a spiral with cut glass, using Matthew’s description of the clouds turning.

That’s how Redemption Window came about. So, I built a replica and said, “This is what I’m talking about, Joe.” I thought he was going to have a heart attack. He just said, “Oh, my God.”

But here’s the thing. I despise flat windows. Architects spend all this time on façade and cladding, but no one ever looks at the damn windows. I was working on two-sided windows before this project came. So, what you see on one side is different than what you see on the other; it’s dimensional. Again, the universe gave me the idea in the early ‘90s and I was working on this stuff. I knew it would give me a chance to do it, and there it was. So, I built Redemption Window, the first 3D window that punches out into real space.

Let’s go back to the anger part. I despise this notion that you have to go into a place to find the sacred—like a church, a temple, a synagogue. We are sacred. We carry it. So the window almost comes out into the parking lot, like an aquarium. It’s out there, so that the sacred can be anywhere. That’s how that came about.

works: This is good medicine talking to you, Pat, if you ask me.

Pat: You know what, Richard? When I had office hours at school, one of the kids crossed out the words “Office Hours” and wrote “Pat Chats.” That’s where I got the idea. They would say, “Uh-oh, time for a Pat Chat.” We’re having a Pat Chat.

works: Okay. Tell me about the inner aspect of it. You must have some feeling for the word “redemption.” Say something about this inner part.

Pat: Okay. God, you’re hitting these really meaty questions, Richard. Okay. When I came back to my studio and made this 3D model, I’d get these hits in my head—Redemption Window. Then I said to myself, “I don’t know if I believe that.”

It opened up this thing—am I going to focus on the promise or the suffering? I really had to come to grips with that. I didn’t know where I fell on that. I finally opted for redemption, the promise. We have to find that promise. Our life is about moments of redemption. So, once I made peace with that and I knew, then I threw myself into it. Redemption Window, yes.

works: I’m touched by that piece. You know, I’m not an “official artist” because I didn’t go to art school…

Pat: Bless your heart.

works: But I’m still kind of picky. I don’t want to put stuff in the magazine that doesn’t speak to me in a certain way. It’s an ongoing challenge. I think people are starved for something that’s real and that touches their hearts—let’s put it that way.

Pat: I agree.

works: I mean, you can talk about this. In all the years you’ve been doing what you’ve been doing—when people are given a certain kind of nourishment, do you feel how hungry they are, how hungry we are?

Pat: Yes. Yes, I can. I feel it. I see it. That was part of the reason why I started doing the PatChats. I wanted to put stuff out there, but in terms of work, we know what’s authentic based on what we resonate with. Kids will say, “How do you know it’s art?”

I said, “It’s like falling in love. You don’t need your best friend tapping you on the shoulder saying, ‘Oh, you’re going to like that guy or that woman blah, blah, blah.’ You just feel it.” When something resonates to that unspeakable, it goes so deep. It’s familiar, and, then you know there’s a connection.

works: Yes, that’s it. It’s mysterious. Sometimes, all you need is just a little glimpse, and boom—you know something’s there. I don’t know if you’ve had that experience?

Pat: Oh, yes. Yes, I have.

works: It’s almost like a magical thing.

Pat: Yeah. It is magical. It happened to me when I was installing my industrial paintings in downtown Minneapolis in the Mayo Clinic building. There’s a public walkthrough, so people saw these industrial paintings, and they were talking to me like I was their cousin from Indiana. They’d say, “You know, my grandpa worked at that,” or “I remember when…” It wasn’t just one or two people; it was through the whole day. And I thought, “What is happening here?” They’re talking to me like I’m an old friend or part of the family. That shocked me, really.

works: I think what you’re describing shows—how to put it? Maybe just that the work is true. You know, your industrial paintings—there’s real beauty in them. What caused you to want to paint those?

Pat: My passion is for geometry. Okay? I was doing glass labyrinths, and then I started feeling that hit again. I felt like I had to do more to bring my work from the ancient into modern day. But I didn’t know what it meant. I get these hits and I think, “Why must these hits be always cryptic?

So, I started looking at these ancient maps and I was struck by the geometry that organized them. So I started making these paintings of city maps—Detroit, Akron. I did a 6’ butyl rubber map of Akron, Ohio It’s what they make tires out of. Akron was the rubber capital of the world. There were 153 tire factories there. Of course, I’m going to make a painting on black butyl rubber. So, I get it. I think, “How is this even going to work?” I always have that dialog. Then I made the painting.

After doing these paintings, I wanted to get closer to the building. I realized I was flying overhead of these industrial cities, and my work is about place as memory—that what is absent is not forgotten.

That phrase kept coming through to me. I was in Detroit at graduate school in the 70s when everything was getting shut down. When you live through that and see a city just imploding on itself, it gets real. But I ran away from that. I came out here (to Minnesota). But doing these works, I started thinking, “I’ve got to get into the factory. I’ve got to get closer. The walls can talk to me.” And that’s when I started. But those bridge structures—that’s pure geometry! I mean, I can’t tell you the number of times I veered off a road looking at a bridge, or when they’re building houses with the stud walls. I love that beautiful structure. I love engineering. How can you not love those beautiful sites?

.jpg)

works: Yeah, I agree.

Pat: Oh, my God, they’re exquisite! It’s also about honoring those people. It’s not just about the buildings; it’s about what those buildings meant on the national landscape in our collective consciousness. We were able to have a middle-class. We were able to have kids go to college. People could have a life that wasn’t just drudgery. I’m not glorifying those factories. I had family that worked in them, and it was hard damn work. But there has to be some kind of acknowledgment about their place in our collective memory. To me, they’re like archeological digs. I want to excavate them so people can see them.

works: They’re powerful paintings. And you’re interested in the Fibonacci series. Would you say something about that?

Pat: The Fibonacci came out of doing the labyrinths. When you study sacred geometry, and you’re looking at the square, the circle, and the labyrinths, how can you not go towards the Fibonacci sequence? I was obsessed with that for years! It’s all part and parcel of the labyrinth work. Those geometric things are so true and that goes back to that invisible world.

works: Yes. I was going to mention that. I think the Fibonacci series was understood a long time ago; you see this in nature.

Pat: Yes. Sunflower seeds and the patterns.

works: Do you see geometry as connecting to the deep structure of being, somehow?

Pat: Yes. I do. Now, this is only my view as an artist, I’m not quoting anything. It was like truth and beauty. The sacred geometry goes back to that invisible connectivity between nature and us—how we share this world, and the art we make, the beauty we create, or the political statements. There’s beauty in those; everything is connected. So, it’s like a ballast for me. When people say, “That’s how I make sense of the world,” I can be more specific— this geometry is my ballast; it’s a truth I can rely on. It’s older than time.

works: Pavi, what do you think?

Pavi: The phrase that keeps coming up for me as I listen is “universal constants.” And there’s something with the geometry, like the principals that you’re tuning into are things we recognize, and the reason why we recognize them viscerally is because, I think in some ways, they’re in our DNA. Like when you refer to your ancestors, it’s probably literally, encoded in our DNA.

Pat: I would agree.

Pavi: And one of the other threads of thought, especially when you were talking about what’s absent is not forgotten—it reminds me quite a lot of the work coming up now in both the study of trauma and trauma release—this idea that the body keeps the score.

Pat: Oh, yeah. Pavi. In sculpture it’s called material memory. Steel has memory; wood has memory. It’s the same thing.

Pavi: Wow. That’s just phenomenal there. And when you were talking about geometry, I was thinking about the city I grew up in, Madurai, in India. It’s an ancient city and—I’ve heard this so many times, and it just came alive in a new way—it’s built around a 2500-year-old temple, and the temple itself was designed with the geometry of the lotus flower. So, it’s a city built like a mandala. And what does it mean to live our lives within such a structure?

Pat: It has an energy to it.

Pavi: Yes. Then, I was thinking about your work with both Women Behind the Wheel, as well as Joan of Arc. Richard, one of the people you interviewed recently (Rachel Naomi Remen) was a women in medicine at a time when there were very few, and what that meant. So Pat, where you have positioned yourself with the art you’re doing, and where your life has called you—with the fact that you’re a woman in this world. How has that played into things you’ve been drawn to and certain projects that are more than projects?

Pat: I think about that a lot. In the 80s, when I was carried by a gallery, there were only 2 women out of 16. When I did huge projects and had a crew, and people would come to the site, they would always go to the big guy saying, “Is this your piece?” Then when one of my crew would point to me, the person would almost would walk right by me.

I’ve had this my whole life, and any woman who’s near my age has gone through this. I think women still do. That’s why I made Women at the Wheel, the documentary. I made that to say what’s changed in this techno-industrial world. I’m very much a woman. I mean, I’m scrappy. I’ll get in your face, and I cherish this femaleness—this way of being in the world. I think it’s a very powerful thing.

When you look at ancestry and pre-Christian religions, there’s a thing like the Divine Feminine. Before the hunter-gatherer came in, there were these matriarchal societies. I think about that a lot. Maybe as I’m getting older, I’m thinking about these things more, but I think it’s really important that young women see what’s possible. That’s why I want to get out there. I want to support them. I want people to see. So that’s why I made that video.

Again, when we were installing my industrial paintings at the Mayo Clinic building, people kept going to the men in the crew.. The men would say, “No, no. You want to talk to her.” And they’d shake their heads like, “I’ll be damned.” It secretly delighted me; it does.

Pavi: Can you speak a little bit of Joan of Arc and your experience of her?

Pat: Oh, God. You know, I like what I call the badass saints, the ones who for some unknown reason were able to do what they did. When I look at this 19-year-old in the middle of Podunk, France, who is told (from above) that she’s going to save all of France, all she wants to do is go back to her house. How can you not love that?

I mean, it draws me. When Richard talks about that anger, I’ve always had this kind of FU attitude. I gravitate towards those people. I love those people who are pissed. I love that kind of energy.

There’s something about Joan. They kill her. They destroy her, and the Church can’t turn a blind eye to her because she won’t go away. So, in 1926, they decide to canonize her.

What is it about a teenager that won’t go away? You’ve got to ask that question. Mark Twain says it’s the most documented life in the history of the world because it comes from court transcripts. For a kid to say, facing these scary-ass Inquisitors asking, “Well, what was Michael wearing? Was he naked?” And she saying: “Do you think God has not wherewithal to clothe him?” She’s 19. But she has that teenage attitude. She was so scared, and yet, she was guided. She was loved, and she did what she had to do. Whenever I’ve been scared in my life, I think of her and I just say, “Joan, help me here. I can’t do this. I’m scared.”

When I went through my divorce, I was scared. My family was in Michigan. I was by myself. I had a daughter. I was so scared, and I was closed. Italians—we kind of keep things to ourselves. You don’t talk to outsiders unless it’s family. I’m done with that! I’m Americanized! Okay? But at that time, I wasn’t. So, when I’ve been scared—Joan is a warrior, and I can’t imagine a warrior in life that has not been scared before doing battle—she is always with me.

Pavi: Can you share that story when a student in your class recently asked you about what your aspiration was, and your dream?

Pat: So, we’re in class and the kids are in there and they’re always talking. When they make art, oh, my God, the things I hear. So I tell them, “I’m not Dear Abby, so nobody can be embarrassed and cringe. Knock it off.”

So, they were talking about what they would do, or what they would have in life, and one of them said to me, “Hey, B…” (they call me B) “Hey, B. If you could have anything in life, what would it be?”

And Pavi, in a nanosecond it came out of my mouth, “I want a Joan of Arc heart, a heart that will stay intact, no matter what. A heart so sure of its substance that it cannot burn.” And especially now, we all need a heart that will stay intact.

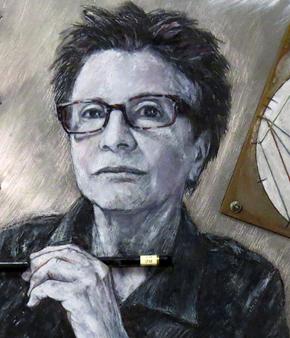

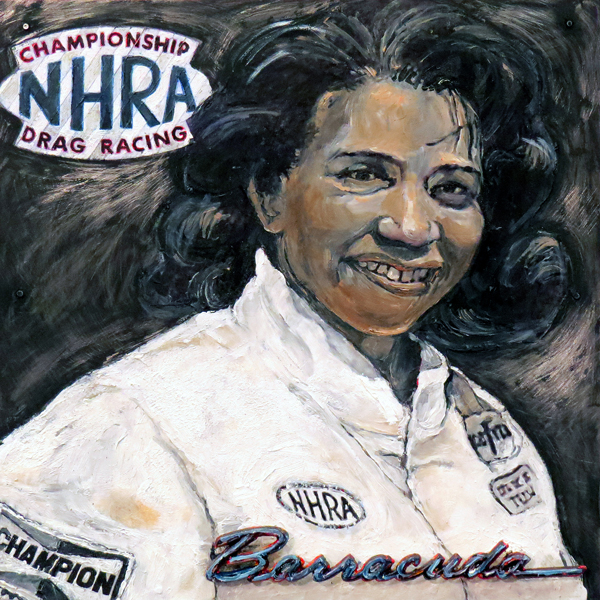

Pat Benincase's works in order from the top:

1. Portrait of the Artist In Proximity, 2015 [detail], encaustic, color pencils, polyurethane with pencil and steel plate on sheet metal, 12” x 16” x 2 ”

2. Falling Water Skylight, 1995, seven-ton, glass and steel skylight sculpture for the Grand Stair Hall of Minnesota Judicial Center, State Capitol Grounds, 14’ x 30’ x 6’ - Photograph by George Heinrich

3. Redemption Window, 2004, Hill-Murray Chapel, Maplewood, MN, 14’x 8’ x 6,’ glass, steel, limestone rock, 34 windows

4. Ore Yard, Pennsylvania, 2013, Encaustic, oil paint, cement, wood on sheet metal, 24” x 36” x 2”

5. Inside Iron Sky, 2014, Encaustic, paint, wood, cement on sheet metal, 24” x 36” x 2.5”

6. And Yet The Center Holds, 2010, Encaustic, oil paint, wood on panel, 21.25" x 21" x 4”

7. Nitro Nellie Goins, 2015, Encaustic, paint on sheet metal with 1968 Barracuda fender plate, 12” x 12” x 1.5” from Women At The Wheel Series (WATW) Watch Benincasa's video of the 13 women portrayed in this series. The series spans the history of the automobile from the 1900's to present day. "From inventing windshield wipers and brake lights to setting speed records in national/international racing events, or inventing Kevlar, or making interior design a key automotive component, these women created a mobility of possibilities that resulted in women's suffrage and opened doors to work opportunities beyond color and economic barriers.

Women made tremendous contributions to the techno-industrial landscape, and their stories restore a missing narrative in our collective memory."

8. Joan of Arc Scroll Medal - from Benincasa's website -

"I designed the St. Joan of Arc Scroll Medal for our military women, men and their families. This medal has gone world wide as Confirmation gifts, keepsakes for someone going through a difficult time or illness, to people who love Joan of Arc. It is 1.5" high, and made with a durable metal with antique brass finish with a reinforced hoop. The medal comes with a note card telling the story of Joan and why the medal was made. On the front it has: "St. Joan of Arc" and "Be at my side."

About the Author

Richard Whittaker is the founding editor of works & conversations and West Coast editor of Parabola magazine.

Pavithra Mehta is co-editor of www.dailygood.org and co-author of Infinite Vision: The World's Greatest Business Case for Compassion

Pat Benincasa is an award-winning artist, documentary maker and educator. She has received a National Percent for Art and General Services Administration (GSA) Art In Architecture Commissions and did an Artist Residency at the Toronto School of Art. Her work is archived at the Minnesota Historical Society and is in collections around the country. She lives in St. Paul.

SUBSCRIBE NOW

TO OUR MONTHLY NEWSLETTER

Share Your Comments and Reflections on this Conversation:

On May 6, 2020 Gayathri Ramachandran wrote:

Dear Pat, Richard and Pavi, Thank you so much for this. I've read it through twice now and I offer the gift of my tears and a sense of tender gratitude in return for this "work and conversation"On May 5, 2020 Elizabeth wrote:

Amazing interview. Insightful. Deeply moving. Thank you for sharing this conversation.On May 3, 2020 martina wrote:

Thanks for this fabulous wonderful amazing interview. YES! I want a Joan of Arc heart that will not burn! I want to work like she works! YAY. Bravo. And THANK YOU!On May 3, 2020 Carol Beth Icard wrote:

This interview is just stunning. I am forwarding it to many friends, and have copied down some of her dialogue with you so that I can savor it. thank you for this gift in my day.On May 3, 2020 Richard D Naylor wrote:

Twice during the reading of this article I wept...have no clue. A life long musician in my eighth decade I am grateful to be able to be emotionally touched by the artistry/dedication/skill of others...especially in these times. Thank you for this article...It arrived when needed.On May 3, 2020 Patrick Watters wrote:

So good, so humanly powerful . . .My “art†is storytelling. I always return to it. My mother’s was simple, gorgeous pencil drawings. She was a wizard with a pencil for a wand.

}:- a.m. (anonemoose monk)

On May 3, 2020 Robert L. Savino wrote:

I'm a poet and artist, still cranking out good poems at 78. But the artwork has gone mostly dormant now for two years. "Is that finished for me now?" I thought. No, I don't want to shut that door inside me! So today comes Pat's Chat, truly my Daily Good! Every word is Manna to my soul. Now I'm going to get out my "Toys" again, and just PLAY. God bless you, Pat. You've joined the pantheon of my Sheroes and Heroes!On Apr 16, 2020 Monica Thompson wrote:

Revealing article capturing Pat & her many talents.