Interviewsand Articles

A Conversation with Doug Burgess: Weeds

by Richard Whittaker, Dec 4, 2004

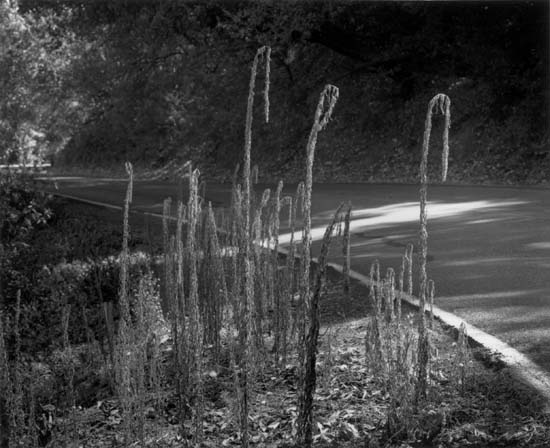

On the walls of the Photo Lab in west Berkeley where I take my black and white film for processing, there’s always a photo exhibit on display. This one came with a xeroxed eleven page catalog: "Weeds" by Doug Burgess, in which he describes weeds as our constant companions. He adds, "The relationship between weeds and people may be one of our most enduring relationships with the natural world.”

As a kid, like Burgess, I too was given the task of removing weeds from the front lawn, but Burgess’ career of weed-pulling extended through his teen-age years and beyond. “As a middling bureaucrat,” he writes, “I often pulled weeds as a form of therapy.” He adds that after more than a half-century of weeding, he still did not have a single weed-free patch to show for his efforts.

Finally, Burgess—as he put it—“went over to the dark side” moving to a neighborhood where no one worries about weeds. Now he names the weeds he finds in his yard and follows their life-cycle. If his family is less than supportive, at least his dog is, he tells us. She “avidly collects burrs, stickers, dried leaves, and other plant parts” for Burgess to study.

I asked Burgess to come over to my house so we could talk about his interest in weeds and photography. I warned him I might take out my recorder…

Richard Whittaker: What turned you toward photography?

Doug Burgess: I had been taking a few sculpture courses at Michigan State University, but I didn’t have the resources available to meet the physical requirements for space  and for the tools and materials needed for pursuing sculpture. Photography seemed like it might be a way to move toward doing the same thing with fewer resources, although I didn’t know what that meant exactly.

and for the tools and materials needed for pursuing sculpture. Photography seemed like it might be a way to move toward doing the same thing with fewer resources, although I didn’t know what that meant exactly.

RW: Were you an art major?

DB: No, but I took a few art courses.

RW: You make a living as a mechanical engineer, but you’ve maintained a connection with photography all these years, right?

DB: Yes. I’ve actively pursued it. Usually I’ve had a darkroom in my home, in a closet, or whatever it took. [laughs] In fact sometimes I feel schizophrenic—living in two worlds. Essentially I’ve been photographing steadily since about 1967.

RW: So what is it about photography that’s held your interest all those years?

DB: One, I can do it independently. Since I’ve made my living all these years as an engineer, I haven’t had a lot of time during the day. Many of the subjects I’ve chosen to pursue over the years have had to fit in this way. For instance, I did night photography for a long time.

And I guess it’s my way of probing the world. In the end the photograph you produce is what the viewer sees, but the process I go through to make the photograph is not in the photograph. The viewer doesn’t see that, and that’s a very personal thing. You could call it therapy. That process is just as important for me as the finished print.

RW: Could you say more about that?

DB: Well, it’s something that causes me to interact with the world in a way I wouldn’t do otherwise. As I said, I’m not around during the day to photograph, and so I’ve gone out at night. I wouldn’t do that otherwise.

With regard to the weeds, two or three years ago, one weed was the same as another for me. That’s changed now. So this process produces a kind of knowledge. It makes me feel like I know the world I live in much better. That’s very rewarding.

From pursuing this process I can go anyplace and feel that I have friends and knowledge. I mean I know the weeds by name now and know a little about them. Maybe it’s one of the major tools I’ve found to come to some sort of ease with the world.

RW: When you say "I have friends in the world" it evokes a sense of connectedness we all must yearn for in some way.

DB: I certainly feel like I belong more than I did before. Even though I grew up in the same home and went to the same school, I still didn’t feel like I belonged in the community, for some reason. Even living in a small community didn’t make me feel like I belonged.

I enjoy knowing people in the community, going to the coffee shop, and I have lots of social interaction, but that’s not quite the same as somehow having a connection to the place, not just the people and the roads, but a bigger sense of that place. It’s really important to me, and this is one of the ways I do it.

RW: It sounds like an inspired strategy you’ve hit upon, this way of entering into where you are in a deeper way.

DB: It’s true. For many decades I’ve felt a very strong need to somehow make that connection to place. I think there are a lot of ways to do it. I imagine bird-watching would be an example.

RW: What you’re describing is probably a widespread condition. Most of us, because of the way we live, are more and more disconnected from place. People have their jobs, tv and their computers. Given this, to what extent do you think one is able to find a real connection with place?

DB: I think if you go back a few generations, people had a very strong connection with place. But I don’t want to make it sound like we’re bad and the people who came before us are good. They grew up on the farm, they had to take care of the animals, mend the roof. They were lucky if they knew forty or fifty people. But they also had a much rougher life than we have. We have enough to eat, there’s medical care, opportunities and so on.

But this connection is something we’re missing. Many times people seem to have this duality—"natural" things and "unnatural" things. We’ve traded some natural things for what many would call unnatural things. I have this terrible need for a connection with place, but I also live in a society and a time that’s so wealthy that I can afford to take time to do that. I don’t think I necessarily want to go back to the time people lived on the farm and never left it.

RW: Okay. Let’s talk about your project with weeds. How did this come about?

DB: It was actually sort of a side trip. I had decided I wanted to know more about the plant life that’s around. I’d studied a little about learning to identify trees and so on. When I finally had some time to learn some of the plants—if you’ve ever gotten some botany books and looked at the keys to identify plants, they work fine for people who already know the plants, but they’re very difficult to use otherwise.

RW: I’ve tried that a little and I agree. It’s difficult.

DB: Very difficult. The most common plants that I saw were the weeds, and I learned that the "real" plant books didn’t cover them. That made me think that weeds are transparently close to us—very close. And yet we don’t see them.

There was something about that, their being right in front of us and our not seeing them, that made me think this really needed to be looked at. At least, I wanted to look at this, and I found it’s very difficult to find out about weeds.

There’s an initial layer that comes out of the agricultural industry about how to identify weeds—and how to kill them. Then there’s a second level that has to do more with gardening, and again it’s about how to identify them and how to eradicate them. These sources didn’t say much about where they came from or why one plant was a weed and another wasn’t a weed. There are a few wonderful books about weeds, though. One that I found most interesting is by Sarah Stein. My Weeds.

I finally arrived at the point of seeing that a "weed" is a social definition—a plant growing where "someone doesn’t want it to grow."

Stein’s observation is that this may be true, but if she has some flowers in the flower garden growing in the wrong place, she can move them and they will stay moved. Weeds, on the other hand, are not so agreeable. She could move them, or even kill them, and they still come back. Here we have plants going on the endangered list all the time and yet in many cases, we’ve carried on war with some of these weeds for thousands of years! The more we try to get rid of them, the more they thrive! So there must be some secret in there.

It opened lots of interesting questions when I began to ask "What is a weed? How are they treated? and why do they grow or why they don’t grow.

RW: Your phrase "they are transparently close," I think that’s very interesting. Where does that thought come from?

DB: That may have actually come from photographing. If you’re standing in front of a chain link fence and taking a picture of something behind it, if you’re focusing far enough away, you will not see that fence. It will, in fact, be right in front of you, but it will be totally transparent. So it may come from this experience. That something could be right in front of you and you would not see it.

RW: It’s a principle that could have wider implications, don’t you think?

DB: Yes. It’s very hard to view something when you’re in the middle of it. It’s very hard to see your own culture, for instance. When you’re actually a part of a process it’s very hard. I think maybe there’s a lot of the world that’s "transparently close" to us.

RW: Have you ever wondered how that might apply more personally?

DB: I certainly know my experience, which I don’t think is any different than anybody else’s, that when you look back in time you certainly see things differently. Maybe that’s what regret is. And maybe "transparently close" applies also temporally. We certainly take a different perspective after time has gone by.

RW: And you’ve spent a year on this project.

DB: Actually I’ve been photographing the weeds for four years.

RW: Do you think that being involved in this process of focusing on weeds, being that they are humble and overlooked, has caused other things to come up, maybe even unexpectedly?

DB: When I photograph these weeds—and in the process of photographing them, you create an abstraction, it gives one a little distance—one of the things I’ve noticed is that some of them are very beautiful.

It makes you think. If something that is so common and lowly is beautiful, the idea of what is beautiful gets to be a little confusing. A face is beautiful, a tree is beautiful. A fabric is beautiful.

Somehow there must be a commonalty, but I’m beginning to think that there isn’t a commonalty. We see each of those things as being gratifying for different reasons.

When it comes to the plant world, we find things very gratifying. Trees in winter without their leaves can be just wonderful things to look at. Flowers are beautiful, then we begin looking at weeds and they’re beautiful too. So is there no plant that isn’t beautiful? If there is no plant that isn’t beautiful, then what is it that makes us think "that’s beautiful"? What does that mean? But I don’t want to take on faces and models and fabrics. Just one thing at a time: weeds. Why are they beautiful?

Recently I’ve gone back and done some reading on fractal geometry. In the last couple of decades three areas of mathematics have been popularized. One is chaos, which is really "bounded chaos," and one is fractal geometry and one is networks. Using both the network studies and fractal geometry it’s interesting that we’re able to make pictures that look like the real world—the way trees branch, the distribution of trees on a hill, the way the hills look and so on. With networks, the way nodes work has some similarity with the way brains work and how the cells work. We may have some intrinsic recognition of patterns or processes that reflect us, and maybe we find these things beautiful because the same processes are at work in us.

I’ve got to explore that some more. I think there might be a possibility there. Looking at this leaf in the way it divides and sub-divides and sub-divides again. Obviously there’s a pattern there, but it’s not a perfect pattern. There’s always lots of variation and yet we still recognize it as a pattern.

We can go out and look at certain species of trees—the buckeye is really beautiful around here in the winter. It loses its leaves early and has this kind of white bark. The small trees have a rounded shape. As they get bigger, they’re not always rounded, but you can recognize a buckeye in the winter landscape even though no two trees are alike. There is some similarity that we are able to recognize. It may reflect something that is inside us.

RW: Yes. For instance, I’ve learned to recognize poison oak—I don’t care what shape it’s in or what time of year I see it!

DB: It’s amazing! And it has this immense variation, you know! It can have different color leaves, shiny, dull, red, green. it can be a vine, a shrub. I can even recognize it without its leaves in winter.

How can we recognize this thing with this immense variation? This weekend I was walking around and I was thinking, "there’s poison oak, there’s poison oak again!" even though there wasn’t a leaf on these things.

RW: Today we think of knowledge as power, but in earlier times, as an acquaintance was telling me recently—particularly if you go back to Plato—but even up to maybe the middle ages, knowledge was thought to be an entry into participating in the mind of God. Why did I just think of that? Because of what you are describing, that these recognitions of patterns in nature may reflect what we ourselves are.

DB: Yes. But I think, just as we’ve given up some attachment to place and we struggle to get that back, that we have been on a very long march of losing some of our humanity. I think it has to do with—in current words—consumerism. Previous to that it was "capitalism." It goes back hundreds of years—from the point at which people began evaluating things in terms of their marketability. Things are worth what you can sell them for. As we have moved farther and farther down this road, more and more things have become things you can sell.

If you were to go back just fifty years and were to ask, what is a tree worth, they’d say, oh, you can’t put a value on a tree! If you’re going to build a project and want to take out three trees that are not supposed to be taken out, you make some mitigation somewhere to decide what they’re worth and you take them out. We’re doing the same thing with body parts. There’s clearly a market developing there.

Something is going on here that I find kind of frightening. If you can buy and sell it, it must be okay. I want to enjoy the fruits of it, but I’m a little frightened about where it is taking us. We see lots of examples.

Probably there are a few remaining places still trying to hold out. Religion might be one of them, but even there I think they’re having some trouble. I’m not a Catholic, but I suspect if you were to look around the world you’d find that Catholicism in the nations that are wealthy is very different from Catholicism in other countries. I suspect it’s had to accommodate this market mentality.

It’s getting pretty close to where there isn’t much you can’t buy and sell. If you have a factory and you’re going to exceed the limits for polluting the air, if you can find a factory somewhere else operating at below the limits, you can buy pollution rights from it.

I know that one of the problems the California Indians had when the Europeans came was that they didn’t understand that you could own an animal. When they began to slaughter the settlers’ animals, it was inconceivable to them that the settlers, as individuals, could own those animals. As a group, you could control a territory where you had a right to take animals, but you didn’t own them.

We buy and sell sunshine. If you build on a lot and your neighbor grows a tree that blocks your sunlight, you can make him cut it down—in a lot of jurisdictions. Clearly with genetic engineering and what’s happening with being able to modify actual life forms…but I’m getting off the subject.

RW: I share your concerns. In light of what you’ve just said, I wonder if you can speculate about what relationship your photography has to all that?

DB: The kind of probing, the kind of knowledge I get from doing it, I don’t think that can be taken away. I don’t think it can be sold. It can’t be marketed.

In a very flip way, but with a kind of serious undertone, one of the wonderful things about photographing weeds is that they are everywhere, and they’re cheap. Nobody wants them. Nobody can ever take them away, because they’ll always be around.

So in a very strange way, photographing the weeds is something that can not enter the marketplace very well. Maybe it’s a small rebellion against the marketplace. There are immense chemical industries trying to kill the weeds, but somehow they are surviving. So I have established this relationship with part of the world that is doing very well despite the market economy.

Something is going on here that I find kind of frightening. If you can buy and sell it, it must be okay. I want to enjoy the fruits of it, but I’m a little frightened about where it is taking us. We see lots of examples.

Probably there are a few remaining places still trying to hold out. Religion might be one of them, but even there I think they’re having some trouble. I’m not a Catholic, but I suspect if you were to look around the world you’d find that Catholicism in the nations that are wealthy is very different from Catholicism in other countries. I suspect it’s had to accommodate this market mentality.

It’s getting pretty close to where there isn’t much you can’t buy and sell. If you have a factory and you’re going to exceed the limits for polluting the air, you can find a factory somewhere else operating at below the limits, and you can buy pollution rights from it.

I know that one of the problems the California Indians had when the Europeans came was that they didn’t understand you could own an animal. They began to slaughter the settlers’ animals because it was inconceivable that the settlers, as individuals, could own those animals. A group could control a territory and have a right to take animals, but you didn’t own them.

We buy and sell sunshine. If you build on a lot and your neighbor grows a tree that blocks your sunlight, you can make him cut it down—in a lot of jurisdictions. Clearly with genetic engineering and what’s happening with being able to modify actual life forms…but I’m getting off the subject.

RW: I share your concerns. In light of what you’ve just said, I wonder if you can speculate about what relationship your photography has to all that?

DB: The kind of probing, the kind of knowledge I get from doing it, I don’t think that can be taken away. I don’t think it can be sold. It can’t be marketed.

In a very flip way, but with a kind of serious undertone, one of the wonderful things about photographing weeds is that they are everywhere, and they’re cheap. Nobody wants them. Nobody can ever take them away, because they’ll always be around.

So in a very strange way, photographing the weeds is something that can not enter the marketplace very well. Maybe it’s a small rebellion against the marketplace. There are immense chemical industries trying to kill the weeds, but somehow they are surviving. So I have established this relationship with part of the world that is doing very well despite the market economy. ∆

About the Author

Richard Whittaker is the founding editor of works & conversations and West Coast editor of Parabola magazine.

SUBSCRIBE NOW

TO OUR MONTHLY NEWSLETTER

Share Your Comments and Reflections on this Conversation:

On Jun 5, 2019 Cynthia wrote:

Very interesting interview and hobby. Doug makes it obvious that he gains much from his study of weeds. It really does sound as if this focus in his photography is like a therapy for him.On Jun 5, 2019 shadakshary wrote:

InterestingOn Jun 5, 2019 susan curry wrote:

As a gardener and herbalist, I have a year-round relationship to "weeds." I loved how Burgess connected his learning about weeds as a means of growing his sense of place and of belonging to the natural world. I feel a kinship with all the breathers. I refer to Family Earth to evoke a sense of stewardship for all the species who have emerged from the same great Flaring Forth and now share this Earth home with us.Many of the so called weeds have health support benefits: dandelions, plantain, chickweed. I became fascinated with the different strategies that different plants have developed for relocating their offspring into other locations. I have become annoyed with rhizome grasses and mugwort and other plants that travel by way of underground roots. The strategies for getting their seeds from one place to another are quite remarkable. Weeds are just more successful, and therefore more aggressive. I wonder how the meek can inherit the earth with such dominating species. Long live life on earth!

On Jun 5, 2019 Alice Kast wrote:

I'm back after reading this and filing it for spiritual direction. I grew up on a dead end street in the foothills of Big Blue and local quarries. My days were spent in nature walking with the spirits of indigenous 'Indians of Massachusetts. On our end of the street families gardened,shared everything and lived as community. My connection to the land, is in me. At 79 I have learned to see people the same way as any growing species. Seed Alice grew roots in Milton, MA, Vermont and Germany. Now that I am confined that seed is still growing. My spiritual home is a garden in Milton, MA, where I spent many years sitting quietly with all nature. My garden experiences in my imagination are all gardens I have ever grown and inhabited. There is a spirit in me who would like to be back in Milton letting my body shell become one with it all...in the beginning. May have to settle for asking my family to sprinkle my ashes there. Thanks, again for the chance for memories. This time I write as alicekatherine my maternal and paternal roots joined as one.On Jun 5, 2019 Alice Kast wrote:

I have not read this yet. My inner response to intro was to remember that I have always loved what people called weeds for their beauty. In our time people are weeds. It will be deeply instructive for my Spirit being to see if there can be connections to my response I AM A WEED.Thank you.

On Mar 27, 2010 Kate wrote:

As one other person mentioned, plants are given the "weed" label when they don't fill the beauty/useful mold. We have a fellow in our communtiy garden here in Honolulu who goes a long way to identifying plants others label as weeds. Many of them he has introduced me to are edible (the nut from nut grass). This great article furthers my appreciation of "weeds."On Mar 26, 2010 chitra patnaik wrote:

Weeds are like the our creative mind.Beautiful shape and worth watching.It gives so many ideas and thoughts you can go on watching for ever.Being a painter this is one of my topic.enjoyed your article.On Mar 26, 2010 A New Spiritual Messenger wrote:

A Spiritual Message for YouHello,

Our beliefs are very important. Not only do our beliefs greatly affect our current day-to-day lives, more importantly, our beliefs will greatly affect our afterlife.

And so I'd like to share these three spiritual beliefs with you:

1) We are all Perfect, Eternal/Timeless Spiritual Beings living in a realm of Perfect Harmony.

2) Yet it seems to us that we are imperfect human beings living in an imperfect world. Why?

3) Eventually, we will all return back Home to our original state of existence: Perfect Eternal/Timeless Spiritual Beings living in a realm of Perfect Harmony.

How to practice these beliefs:

Our first thought after we awake should be a positive, spiritual thought, looking forward with "positive expectancy" towards the new day. For example, we can repeat belief #1.

Sometime during the day read beliefs #1 and #2, ending with asking the question Why? Then spend some time silently waiting for a reply. We all have an Internal Guide/Spiritual Companion that will lead us towards Harmony.

Our last thought of the day should also be a positive, spiritual thought, looking back on the day with "gratitude", looking forward with "hope and trust" to awaking from sleep one step closer to Harmony. For example, we can repeat belief #3.

That's all there is to it. Try this for 30 days. If you find that it benefits you, continue; if not, don't.

Wishing you Harmony,

A New Spiritual Messenger

On Mar 26, 2010 Theresa Clarkson-Farrell wrote:

This is a wonderful article on several levels the artistic/crreative procees described. I think its telling that doug works in B&W in"old Fashioned"film! the comments and connections with consumerism and the natural world. I have always had a "good"relationship with weeds! basically if I Like the way it looks it stays in the yard. I do weed out weeds in the Veggie patch etc. But I'll trim wild briars so they can stay in the garden with out over running othrer plants!I beleive that it's only fair to root out weeds by hand it seems wrong not just enviromentally but well unfair to use herbicides.I think the lesson here is look really look to see you may find some new friends!

On Mar 26, 2010 Carolyn wrote:

I loved this article and also believe that weeds are beautiful. A plant is only a weed when it is unwanted! Thank you for your work Douglas and for your interview and article Richard.On Mar 26, 2010 cricket wrote:

i really enjoyed reading this interview. my family and i live in a very wooded three acre lot, and my yard is the forest floor. i hated it at first, but it seems that every year when these beloved weeds begin to bloom, my yard becomes beautiful to me once more. we have a special flower bed for mullein, and my entire front yard is dedicated to queen anns lace, black eyed susan, and chicory. it just feels good to see what ought to be there in a forest floor... actually be there. it is life in its simplest and purest form i believe and we could all learn a lot from nature. thank you for your article.On Mar 26, 2010 Gurudatt Kundapurkar wrote:

What a fascinating conversation between Richard & Doug on one of the most so-called trivial subject, weeds! Only a sensitive and empathetic Richard could understand and reveal through Doug's words what a deep lover of nature at grossest level the latter is. Doug is an artist and a philosopher rolled into one, in a world which completely misses out weeds, the nature's wonder under its own feet!On Mar 26, 2010 Tomaca wrote:

I appreciated reading this. It's true; weeds are everywhere and don't go away despite man's constant struggle to eliminate them. I see some of them as being very beautiful also. Interesting perspective. I would like to know where I can see some of his photography. Is there a link somewhere? Or a book perhaps? Thanks.On Jan 23, 2008 John D Brown wrote:

This was an interesting conversation. Interesting for me as a farmer who had a heritage of war thinking and technology as the approach to raising food. A few years after engaging in the process of Conscientious Objector designation in 1970, I had the opportunity to take over the family farm. That started decades of extraction from that domination farming and movement toward a way of growing food that was benevolent and collaborative. The evolution of relationship with life forms of all kinds has been a rich journey. I see a similar journey exposed in this conversation with Doug and Richard. Thanks for the company on the way to exploring a world.John