Interviewsand Articles

Premier Autobody

Premier Autobody

by Richard Whittaker, Aug 2, 2020

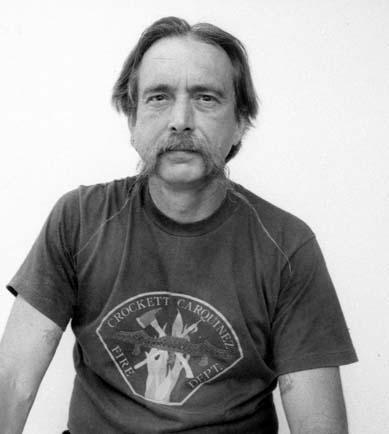

Artist, polymath and friend, John Toki told me about Russ. It was years ago and I imagine it went like this: “Richard, do you know Russ McClure? No? You should meet Russ. He’s—and here John would have laughed because—where were the words? It was always a tip off.

Spending time with Russ is like pulling into the fast lane. You have to step on the accelerator to keep up. And if the sudden lane-switch ends with a collision, no worries. McClure runs Premier Autobody in Berkeley, California. He’s a master at taking out dents, matching paint colors and getting you in shape in a hurry—all without overlooking the details. Time is precious, after all, and life too rich to waste—which gets us to the beginning of this story. Russ has another life; he’s an art collector. As I’m sure Toki must have said, “Russ is passionate.”

I was a little shocked the first time I met McClure. Given his name, I halfway expected to hear a bit of Irish or Scottish brogue. So who was this Asian guy? Later, when I felt comfortable enough to ask, he said, “Oh, yes, Richard. My father is Scottish and my mother is Irish! Don’t I look like it?”

Russ was born in Korea. “I was 10 years old when I came to the U.S. My parents were in their 50s when they adopted me. It was unheard of in those days.” His adoptive father was a noted civil engineer who worked for William Randolph Hearst and Julia Morgan. Their biggest project was the Hearst Castle.

We hit it off. Thanks to Russ, I recall the moment

I decided to seek an interview with ceramic artist Vaea Marx. It was at a gathering at McClure’s home. In his living room a particular piece caught me eye. “Wow. Who made that?” I asked him. It happened to be one of Vaea’s.

I’d heard stories about Vaea from John Toki and had been curious, and seeing that piece, now I wanted to interview him.

Vaea agreed to an interview, and it was an occasion for getting to know Russ a little better, too. Besides visits to Vaea’s Oakland studio, there were trips to McClure’s home to take more photos, as he’d collected a lot of Vaea’s work.

Long before I met Vaea, I’d heard stories about him from John Toki. Vaea used to run errands for Peter Voulkos, sometimes borrowing the Toki company truck. Some crazy things happened. Vaea and Voulkos a bit wild? He’d never lost his his French accent, I’d heard. That was true and added something to his charm. Sitting across from him as we talked is an unforgettably sweet memory. (Vaea's story is remarkable and much is told in our long interview.)

But the circumstance that moved me to write this was sparked by Russ McClure. It had to do with a run of bad luck. First my 2007 Prius was the victim of catalytic converter theft. Turns out the cost of repair was more than the car was worth, so adios. Then, just a few days later, my wife drove our other Prius up to idyllic Point Reyes Station. She parked across from Toby’s Feed Barn and, coming back to the car twenty minutes later, discovered the front end was scrunched in. So I found myself in a second dance with my insurance agent. More to the point, I remembered having a friend in the dent-removing business. It’s what brought my wife and me to Russ’s place one chilly morning in December.

Premier Autobody sits on San Pablo Ave. in a west Berkeley neighborhood that’s home to an intriguing variety of cultural and individual life. The shop sits between a 99 Cents Only Store and the BrasArte World Dance Center, a non-profit that seeks to preserve Brazilian culture. Directly across the street, you can visit the Sacred Rose tattoo parlor, the Indus Village restaurant, a Wells Fargo Bank and the Halal Food and Meat Market. Down the street a block, there’s the Middle East Market, a tapas bar and a Mexican grocery store. Just up the street, you could check out an aikido dojo while around the corner you’d find the Bombay Spice House and the Sari Palace. Just a short block west you could check out Sacred Laughter, “an arts place dedicated to taking life less seriously.” And nearby you could stop in at the Priya Beauty Salon, Mission Hill Baptist Church, Milan Indian Grocery, the Thai Table or Kombucha to the People, where you could sign up for a class. If you wanted to think about it first, you could stroll past Philthy Clean Tattoo, Sukam Copy and Print, Isalia’s Alterations and peek into the Multicultural Institute to see what they’re about.

San Pablo Ave. is a four-lane ribbon of stoplights passing through an international and economic mix from near and far and from the homeless to the well-healed. Beginning in Oakland, it runs north through west Berkeley, the municipalities of Albany, El Cerrito and Richmond, all the way up through Pinole, Hercules and Rodeo to Crockett—home to Clayton Bailey’s Museum of Kaolithic Wonders. It’s hard to mention Clayton Bailey without wanting to share more about this idiosyncratic treasure of an artist. (My 2012 interview with Clayton is comprehensive and a must read for those interested in him.)

So Rue and I parked on San Pablo Ave. in front of Premier Autobody that chilly morning to drop off our scrunched Prius for repair. “Wait until you see what’s inside,” I told her.

A couple of months earlier, I’d met McClure at his shop to go to lunch together. I’d walked in and was astonished to see a large sculpture. Even though it was in two pieces, patched and sprayed with primer, and clearly undergoing restoration, I recognized it immediately. It sat there sharing space with several banged-up cars under the wooden trusses of the old garage’s roof. I stood there looking at it, at a loss for words for a moment, before exclaiming, “Russ, why do you have Joe Slusky’s work in here?“

.jpg)

I’d first seen Joe Slusky’s Ashby Odyssey five years earlier when I’d published a small portfolio of his drawings [works & conversations #19]. I’d visited Joe’s studio and ended up looking through his flat files, where I found some great little pencil sketches. Somewhere about that time, he took me to an old office building in downtown Oakland. I remember the place was completely silent as if none of the offices were actually inhabited. And there in the middle of the building’s foyer on a faded linoleum floor illuminated by a small skylight, sat an extraordinary piece of sculpture. I was astonished. “Jesus, Joe. That’s an amazing piece!” I said. It was Ashby Odyssey.

Joe is another original. He taught at UC Berkeley in the College of Environmental Design for 30 years. And all that time, he was doing his own work as an artist. Although, I knew both Joe and Russ, it had never crossed my mind to put them together in any way. But now, in retrospect, the match-up seems almost inevitable. And come to think about it, Vaea makes three. I see them all as soul brothers.

What I love about this story has to do with an attunement to something that escapes all our prefabricated expectations. It’s like an invisible place that’s always possible to enter, but which mostly remains unoccupied. It’s what we want and recognize in what we call poetry and art. And beyond that, it’s what we want to experience in our lives. Walking into an autobody shop, one doesn’t expect to find a piece of sculpture under repair sitting next to a bent Toyota, a crunched Audi, and a banged-up Dodge Charger. But this was Russ McClure’s autobody shop, where life can be art. And how fitting to find it right on San Pablo Avenue, a zone so rich in life itself. Nowhere in my associations could I have prepared myself for this small revelation. Or perhaps it’s not so small after all.

When we picked up our car, restored to its pre-scrunched, proper carself, we sat in McClure’s office and talked about art. At this point, he had another of Joe’s pieces in his shop for restoration. I’d never seen Kaisersong. On our way home, I marvelled. It seemed like a moment in which another way of living shone forth, something that doesn’t care whether we find just the right words to describe it. ∆

Russ McClure on Joe Slusky’s Ashby Odyssey:

This is a piece made from found metal objects and material from 1969 to 1975. Joe literally did this on his own. He never had assistants like you see nowadays. Teaching at UCB, he was very limited financially. He would go down to the old Judson Steel property in Emeryville before it became Ikea and pick up all these throwaways. He shaped and manipulated and forged them and put this thing together over seven years. It’s called Ashby Odyssey because the work was created on Ashby Ave. where the old bus station was.

What I see, in terms of the European influence, is Futurism from Italy and Suprematism from Russia leading into the Bauhaus School of Walter Gropius, and then coming into the ‘60s with Pop and Funk Art. In terms of the motifs, there are probably six or seven schools of art in this piece. And it’s incredible how they all come together in this one piece. It doesn’t feel like a collage of fragments because it has its own unity.

You don’t realize it, but during those years Joe put the piece down and went to New York and Europe to get more inspiration. He went back and forth that way. I just find it amazing. He was anti-war, and all that—and the piece is emblematic of that, too. The early ‘60s were, I think, the most inspirational time maybe for Joe and for a lot of artists in the Bay Area. It was just like Voulkos’ period in the mid ‘50s up to 1959. That four-year period was just incredible for Peter.

On his parents: They adopted my sister and me in their late 50s, if you can believe it. It was unheard of in those days. My father was Scottish. My mother was Irish. I was born in Korea in 1957 and came to this country in 1967. My father was a very noted engineer who worked for both Julia Morgan and William Randolph Hearst. He was born in 1905. My father always wanted to be an architect, but he was a civil engineer. He went to UC Berkeley and got his degree and then went back to the Castle, where he was the superintendent of construction.

Julia Morgan was the head architect of the Hearst Castle. She called the shots. She was the one—this petite little woman, 4’ 10”—who told the construction people, all these Irish, Italian, Polish laborers what to do. It was an amazing dichotomy.

The Hearst Castle was never finished and my dad retired in 1945. Hearst gave away the “ranch house,” which is what he called it, to the state of California. ∆

Below, foreground - Joe Slusky's Kaisersong in restoration.

About the Author

Richard Whittaker is the founding editor of works & conversations and West Coast editor of Parabola magazine.

SUBSCRIBE NOW

TO OUR MONTHLY NEWSLETTER

Share Your Comments and Reflections on this Conversation:

On Oct 21, 2020 Rishi Chopra wrote:

Seeing this article about Russ in the ServiceSpace newsletter was a special treat; much love to a genuinely kind & wonderful person - Go Bears!On Sep 10, 2020 Jane Ingram Allen wrote:

I really enjoyed this Conversation. It is amazing sometime the serendipities that life brings. Thank you for what you do.