Interviewsand Articles

A Conversation with Camille Seaman - Melting Away

by Camille Seaman, Richard Whittaker, Apr 15, 2021

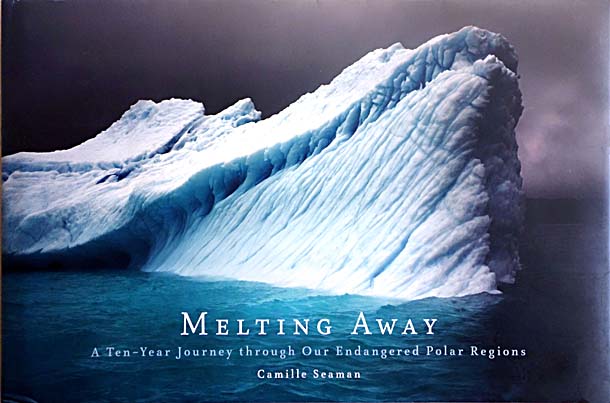

I first met and interviewed Camille Seaman in 2012 and featured her work in w&c #26. Hers is one of those remarkable stories and her photographs are truly sublime. Three years later, I had the chance to speak with her again at Diesel Books in Oakland, CA. She was a featured author and the occasion was the publication of her book Melting Away. Our conversation that evening, while not covering as much territory as our earlier interview, brought her unforgettable stories to a new level of focus.

After some introductory remarks, the bookstore's host handed it over to us, "I encourage you all to take a look through this great book and please join me in welcoming Camille Seaman. (Applause.)

Richard Whittaker: I think those introductory remarks were very astute. This book is extraordinary and Camille’s photographs are really sublime. Are you happy with the reproduction?

Camille Seaman: I am. The colors feel very true to me. Working with that publisher was actually a very smooth process and I have to say, when I saw it, I was like, I did that. It felt good. It felt like the right object to sum up that work. So I was pleased with it.

Richard: That’s great, Camille. Now it’s been a few years since I ran across one of Camille’s photographs. I found out that you lived in Emeryville at that time, and I was just thrilled because your photos spoke to me so deeply. So ultimately, we met and did an interview and I can tell you (the audience) that her story is really quite amazing. I’m sure we’ll only scratch the surface here, but there’s a longer interview with her on the conversations.org website. So, I know we don’t have a whole lot of time, and I was trying to think what’s the best way to approach this.

Camille: How to sum it up. Right?

Richard: Yes. How to make a start on that? And since the photographs are there in the book, I don’t think we need to talk about them right away. You can see them and talk with her later. But Camille, I think your heritage is very interesting. You’ve gotten some very powerful things from it, which as I remember, on your mother’s side, is Italian and African American, and on your father’s side, Shinnecock Native American. Most of us probably don’t have any idea what that might mean, but in talking with you, I got an inkling of some of these things.

I know you lived in Long Island, was it? And I remember you saying that, coming from your background, you felt out of step with the dominant culture, especially with a Native American influence. So, could you reflect a little on some of the most valuable things that you have received from your heritage?

Camille: I'll say that I didn’t know anything else. I really took it for granted and strangely, I thought everybody was raised the way I was until I got to grade school, and then I realized something was different. We were taught, because we are matrilineal, to be leaders as women, and as soon as you got to school, especially in gym class, it was pick the strongest boy for your kickball team. I didn’t understand why the girls were sort of standing back or not stepping forward to take the role. I think that once I started to realize that something was different, I realized that I had to learn to walk in two worlds. I was a hybrid in the sense of my racial mix and ethnicity, and I was a hybrid in that I was raised in a very traditional, Shinnecock way, and also in a very modern, suburban Long Island way- like I was a mall rat.

Something that can help to sum it up is recently I told this to my daughter, and I'll tell you - which is, “You are billions of years in the making. You were born of this time, for this time. There is no one quite like you. You have inherited the strength and wisdom of all of those who came before you. You have survived genocide, slavery, and disease, and really, we need you.” This is the same thing that my grandfather said to me when I was a kid, so I was just passing on to her, finally, that information.

Something that my grandfather did when I was a child - we lived near the woods - he would take me into the woods and literally introduce me to each tree. I would have to hold the tree and he’d say, “Still your breathing. Listen.” And I could start to feel this great thing moving, and understood that it was alive. He said, “This tree is your relative, in the same way that I am your relative, and you must respect it.”

He meant that literally. He caught me once, just pulling the leaves off of a branch without any care, and very gently he said, “You think you’re separate from that tree that you can do whatever you want to it?” He said, “If you think you’re separate from nature, try holding your breath.” This is the way I was raised. I mean that’s just one example, but everything was a lesson. He very actively introduced me to my connections of this living world.

So, even when I think of the wood of these shelves, I know that it had a life, and I honor that it had a life. It’s not just this dead thing that is something else now. That, I didn’t realize, is very different from the way most people are raised on this planet. So, of course, it informed the way that I see, not only as a person, but especially as a photographer. I see from the viewpoint of everything is alive and everything is interconnected and interrelated.

So that is what’s a little different maybe, about my photography. Why is my picture of an iceberg resonating with you in a way that someone else’s picture of an iceberg didn’t? I can only answer personally that I think it’s the intent, that my intention is looking at this thing as a living creature, as a being unto itself, an ancient being, and honoring that it has had a life that we will never comprehend. So, when I photograph it, that’s what I'm feeling and thinking about, and hopefully, if I do it right, you will feel some of that, too.

Richard: And one of the things this relates very much to is what you told me that your grandfather did, which is, to me, must play a very central or big role in your photography also. He would say, “Go outside and find a place and sit still for an hour.” This is a kid, right, seven or eight?

Camille: From age five, kindergarten, to when he died, when I was thirteen.

Richard: For like an hour, sitting still as a kid. How often was this?

Camille: Every day after school, I had to sit outside - rain, snow, heat - it didn’t matter. I chose my favorite spot. We had sort of a picnic table under a beautiful elm tree, so I would sit on top of the thing, and it was not allowed to move more than the circumference of my arms. It was really about being still and observing. Again, like I didn’t realize other kids weren’t being made to do this. The first few times, I would be a little bit… He’d call me in and say, “What did you see?”

I’d say, “I didn’t see nothing, Grandpa.”

He’d say, “Go back outside.”

So you learn pretty quickly to pay attention and observe. What was amazing about that was he would translate what I saw. He taught me what a mackerel sky was. I explained that I saw the sky with this sort of rippling, and he said that means it’s going to rain within 48 hours. Or with a spider building a web, “then no rain this week” - these kinds of things. He was teaching me how to read my world, but he was also teaching me how to be still, how to observe, which, as a photographer, is 90% of the job. It’s about observing and noticing the things that other people just pass by.

Richard: To me, that’s an extraordinary thing. Probably very few of us ever stop for even ten minutes in one place in order just to take it in. If you do, you’ll discover that things begin to appear—sounds, the feel of the wind. I mean it’s really an extraordinarily wonderful exercise.

Camille: I speak a lot to kids in high schools and at the university level and I challenge them; I say, “I’m not asking you to do an hour. Just try three minutes a day. It will change your life. You will start to notice things and be aware of your environment and your life. You will be aware of your life in a very different way.”

Richard: Some little piece of this influence from your grandfather is that you played Babe Ruth baseball, right? I think that in our earlier interview you said you you were the 13th girl that played on a Babe Ruth baseball team. I mean, that’s kind of a factoid.

Camille: Yeah. I was in the newspapers. My family was really proud. There was a picture of me. They drew the line when I asked to play contact football, but they really were like, “You do it!” My grandfather, he’d be like, “Down on one knee. Down on one knee,” with the mitt. I was a pitcher and a catcher and right fielder.

Richard: One of the things that strikes me so strongly about you is that, with all this support and teaching from your grandfather and your parents, you have learned to have a deep trust in yourself. You have some amazing stories, let’s just jump right ahead to how the heck did you get to the snow to begin with? This is a big jump.

Camille: Well, I'll fill it in a little, just so you have some sense of time. When I was a child, my parents would catch me drawing inside the closet on the wall, and underneath the dining room table. I was like a natural graffiti artist. My aunt, my father’s sister said, “Give that girl some paper!”

That was the beginning. I would stay in my room and draw all the time. As a teenager, my mom would punish me by saying, “You have to stay out of your room.” [general laughter] It was like this flip situation. So, as I turned 14, the same aunt who said give her some paper, said, “She really should apply for the Fame High School [in NYC].”

So I did. The test was they crumpled up a brown paper bag, threw it on the table, and said “Draw it.” That was my entrance test to get into this performing and visual arts school. I'm just telling everyone, just for scale, Jennifer Aniston was in my class as a drama student and I was in the visual arts the same year. There are a lot of my classmates who have gone on to do amazing, amazing work.

But moving to the city was really difficult for me. I felt very lost. There was too much concrete, and things started getting weird between me and my mother. She was raised Roman Catholic, but not until my parent’s divorce did she start to apply this to us. We were raised in the woods with this Native American idea of everything being alive, and then suddenly it was about guilt and shame; you have to pray and go to church, and things felt very constricted to me. I also think she didn’t understand me. I mean, I was doing mohawks and blue hair at that age, partly as this kind of trying to find my space in the city, and all my friends in art school were these punk art rock people.

Things got so bad between me and my mom that at the age of fifteen, one morning I left a note for her that said “I have to go. I can’t stay.” So I left and slept on the couches of friends in order to stay in school, and two things happened. One is that the school recognized I was at risk, that I could drop out and fall through the cracks and get pregnant - who knew?

So they put me in an afterschool program where they gave me a Nikkormat camera. But they took away the manual and said, “You have to figure out how to use it yourself.” But they did show me how to bulk-load black and white film, and they also taught me how to develop that film into images in a wet darkroom. They said, “Go out and photograph your experiences.” That probably was one of the things that saved me, because it was a time when I was really angry and confused, and here was this creative and positive thing. I photographed all my punk rock friends and all the mischief we got into.

Now fast forward, I still didn’t see that my life was going anywhere. If not for a great-uncle who sat down with me to fill out a college application and then went with me to mail it off, I don’t think I would have applied to college. He even drove me to university the first day. He wanted to make sure that I did this. It turns out that I'm one of the first women on my father’s side to actually, not only go to college, but finish. I'm the first female on my father’s side not to end up pregnant before I was twenty. I'm the first female to cross the Atlantic - all of these things.

Towards the end of my college career, I was on the subway with my then boyfriend, who was a white Russian. We were coming back from a music performance and were sitting in the very front car of the D train. We fell asleep and the next thing, I hear some sort or ruckus; and then I feel a blow to my nose. My nose is bleeding and I’m like, what's going on? I'm trying to wake up and shake it off and can’t believe someone has struck me. My boyfriend starts to wake up and I realize we’re surrounded by like five guys. One of them is really instigating. He’s giving me a tissue, and saying, “If that was my girlfriend…” He’s trying to start something.

Long story short, he hits me as he exits the train. He hits me so hard that he fractures this bone right above my eye and I just see black. I can’t see anything for almost an hour. The conductor saw the whole thing, and as soon as she could get them off the train, she closed the doors and pulled the alarm. The police were there very quickly. Nobody saw nothing, and what broke my heart was that there were over 40 people in that car with me. I swore that day, “I will never let anyone feel that alone, as I did.”

I felt a bit of PTSD. I couldn’t be on a train without wondering if I might get hit. I was like, this was no way to live. I was really having a hard time. My boyfriend’s mother, this is when you could still fly on someone else’s ticket said, “I've got a ticket to San Francisco. Why don’t you just go for two weeks, just get a breath of fresh air and shake this off.”

So, I went and I found this place. It was like nothing I’d ever seen - the quality of life here. Nobody asked me, “What are you?” It was like stepping into the Renaissance from the Dark Ages. It felt like that. I was like, I want to live here.

When I got back, I told my boyfriend, you can come with me or not, but I'm moving. I arranged with my professors to finish my senior thesis in California and fly back and present it. All that happened, and that’s how I ended up out here.

Richard: Yes. And I remember you have some surfing stories, too. Right?

Camille: All right. I wasn’t always as fearless as I seem. So I'm just going to fast-forward a little. I’m 23 years old and I'm living in Berkeley on 4th and Gilman at the Tannery in a loft with my boyfriend who came with me. Our friend that we had known since we were 16 years old moves out here, and he’s a surfer. At the time, I was working for an architect firm as an admin assistant, and I got laid off. I was like, “Now what?” Oliver, the surfer friend said, “You can come hang out with me while I surf.” So, we would go almost every day to Bolinas and I would watch him surf. After maybe a week, I was like, “I think I want to do that. That looks pretty cool.”

So, we went and we’re at the beach, he’s got me suited up, and he gives me a board. He teaches me three lessons—always come up with your hand over your head; never turn your back on the ocean, and if you get pulled into a wave, don’t tense up. Relax.

I'm like, okay. He failed to mention that the Farallon Islands were just 29 miles away and are a great white shark breeding ground, and that Bolinas lagoon is where sea lions love to hang out, which is where sharks love to catch them.

So, I start to paddle out in this dark, cold, murky water. My balance is very shaky and I freak out. I turn to him and I'm like, “Oliver, I'm afraid.” And my best friend, what does he do? He paddles away. He doesn’t say anything; he just paddles away.

I just got fuming mad, like who does this? So, I struggled for a while and then I was like, forget this! I got out of the water and when he finally comes out, I was like, “How could you do that? I told you that I was afraid.”

He said something that really shifted a lot for me. He said, “No one can teach you to manage your fears except you.”

I was like, “Damn! He’s right.”

So every day after that, every day, I would get in the water and I would work through this feeling of like, okay, what’s the worst thing that could happen? A shark could get you. Well, is that happening now? No. Okay. What’s the second worst thing? That you could drown. Is it happening now? I would just work through it. It taught me to be really present. Pay attention to what’s happening now. When you’re present and you’re paying attention to what’s happening now, you have all the tools available to your senses to take care of anything that’s happening with your mind.

It set me on a course. I was so hooked. I lived in Baja, Mexico for a few months and surfed there. I had just my dog with me. The water got a little warmer and I was like, “This is nice, warm water.” Then I did Hawaii and I was like, “This is really nice, warm water.” And then I was like, “What’s Fiji like?” So I went to Fiji. Then I did New Zealand, and then Australia - just because of Oliver doing this. So, doing all of those trips and traveling alone, you learn more and more of what you’re capable of, and of course, everywhere I went, people were like, “A woman traveling alone? Aren’t you afraid?”

I was like, “What should I be afraid of? What’s the worst thing that could happen to me and is it happening to me now?”

I did have some situations, of course, where things arose, but I think just because of my energy, I was able to befriend those people who initially saw me as a potential victim. For example, in Buenos Aires, I just happened to be walking neighborhood to neighborhood and ended up in the wrong neighborhood. This guy with like the white, sleeveless T-shirt, comes over. My Spanish is okay, and he starts trying to really get my goat. I just took it and I pushed him into a stoop and I just started photographing him. - “No. More like this.”

At first he was like, “What’s happening?”

Then he started getting into it. Then he was calling his friends over. By the end of it, they escorted me back to my hotel and we were like buddies. That’s what I tend to do in almost every situation, where it could go a certain way.

Can I fast-forward now?

Richard: Please. It’s all very inspiring.

Camille: So, when I left home at 15, I promised myself I would never be as unhappy as I was at that moment. By the time I was in my mid-twenties, I’d done all these crazy jobs. I worked as a Backroads tour guide. How many of you have done Backroads? I led hiking and biking trips in Glacier National Park, in the Grand Canyon, Bryce, Zion, and even the Wine Country. I realized I loved being outside - that it made me happy - and I loved traveling and meeting new people. So, I was going to make sure no matter what I did that would be part of my life.

When I was 29, to pay for all this, I was doing my traditional beadwork and making beautiful moccasins and dolls and jewelry. I used traditional brain-tanned, smoked deer. So I was keeping the traditions and was doing really well. I was selling this stuff in galleries across the country and my work was in demand - so much so that I was working ten hours a day, six days a week. One day, I woke up - I was 19 - and my hand was on fire with a pain I’d never felt in my life. A doctor said you have three choices: there’s rest, there’s cortisone shots, and there’s surgery. I was like, let’s see if rest will fix it.

My boyfriend at the time - Kevin, a new guy - had to go on a business trip from Oakland to L.A. He said, "come with me" so we’re waiting at Oakland Airport when Alaska Airlines announces that they’ve overbooked the flight. If someone would give up their seat and take the next flight in just an hour, they would give a free, round-trip ticket anywhere they flew. I was like, I don’t need to go to LA. It’s a free ticket! So I gave up my seat.

I have to tell you, before that moment I had no desire, not even a thought about Alaska. Places like that were for other people, partly because New York winters can be so brutally cold. So the idea of going to some other cold place was just not in my vocabulary - but here was this free ticket.

So, I decided to go to Kotzebue. It's a little place situated on the Bering Strait, right at the supposed Bering Land Bridge. I chose this place because my tribe is at very tip of Long Island as far east as you can go. I thought if we had migrated across this ice bridge long ago, I wanted to see what that felt like. It was just curiosity. I was not a photographer. So I used this ticket to do a sort of reverse commute across the ice.

I did some research before leaving. I knew it was going to be cold, so I went to the North Face outlet and bought some warm clothes. I packed them in a bag, and off I went. I made the mistake of only wearing a polar fleece and some slip-on shoes on the plane, and I checked the bag with all the warm clothes—big mistake.

When I arrived in Kotzebue, it was like nothing I’d ever seen. Even as we were landing, it’s just white. You couldn’t tell the sky from land. I don’t know how they landed the plane. This airport was like a little Quonset hut and they rolled this little thing over to the plane to get you off.

As I stood in the door and was about to step off, I inhaled this minus-30 degree air and my lungs went (makes inhalation sound) and my nose hairs just went (sounds like tinkling ice breaking). I was like, “Whoa! This is really crazy!”

I waited at the tiny carousel, and my bag never came. The women who worked at the airport were all native Inupiat people and they were like, “Don’t worry, sister, we got you.” They completely outfitted me in a sealskin parka, hat, gloves - everything I needed. They said, “When your stuff comes, we’ll get it to you.”

What was really amazing is that within an hour, every male in the town knew a single woman had just arrived and had lost her luggage. How does that work? I’d come across somebody and they’d be like, “You’re the lost-luggage lady, right?”

So, the next morning I was like, “Okay, I'm going to do it!” I had a film camera tucked inside the parka because again, it was minus-30 - probably minus-50 with the windchill. I walked down the slope and then stepped onto the ice. That was the most alive feeling. I even had goggles on because it was so cold, and you have this sort of Darth Vader sound (imitates breathing).

I was like, “This is my extraterrestrial moment.”

So I stepped foot onto the sea ice and started walking. It was really squeaky and dry and wasn’t what I expected. There were little twigs stuck in the ice every ten feet or so, which was the road. I thought, “Wow, there’s even a path.” So I started walking. Every ten minutes or so, a guy would come up on a snowmobile and he’d be like, “Are you okay? Do you need help?”

I’d be like, “I'm just going for a walk.” This happened for a while. There was even some traffic and I thought, “This isn’t so crazy.” So, I walked for some time like this. Then I got to this point where there were no more twigs and no more traffic. Then two snowmobiles pulled up, an Inupiat man and a Russian woman, each on their own snowmobile, and they asked me a different question. They said, “Where are you going?”

In my mind, I really thought I couldwalk to the edge of the ice and then there would be the open sea. I was so naïve and really a bit stupid.

Richard: I mean, I'm just struck by this whole story and how you would just strike out.

Camille: Why not? What’s the worst that could happen? Just a day in the life. Right?

Richard: So these two on snowmobiles proposed that…?

Camille: They said they were going ice fishing, but they weren’t coming back. They’d be happy to give me a ride. They also told me it was 22 miles away, this edge where the sea began. I was like, “Ew, 22 miles.” I have to tell you, I had no water, no food, no shelter - just literally what I was wearing, and my camera tucked in my parka. But I was like, “I've never been on a snowmobile before, why not?” So we take off.

I had no idea snowmobiles - I mean we were going like 60 miles an hour. For a while I thought, “This is really cool.” Then I was like, “Wait a second. I have to walk back.” And I started doing the math - 60 miles an hour times how many minutes. I was like, “Stop, stop!” And they let me off. It was one of the few times I took the camera out. I took a picture of them as they took off. I watched them until they just disappeared into the white and thought, “Wow, that’s really cool.”

Then I turned to look for the town and, “Oh, my God, it’s gone.” In every direction it was just white. I thought, “What have I done?” That’s when I realized that nobody in the entire world knew where I was standing on a frozen sea. There could be a whiteout, there wer polar bears. I realized how much trouble I was potentially in.

Richard: I just think that’s astonishing. I mean, to imagine one’s self in that spot. And something happened there.

Camille: Well, the surf moment kicked in. Don’t panic, relax, turn around right now! Don’t be foolish. Follow those tracks back before the wind blows them away. So, I just started walking. I walked for over five hours before I could see the town again. As I walked, all of my grandfather’s teachings came flooding back. For the first time, in a really physical way, I understood that I was standing on my rock in space. That this extreme place was part of my planet. That I was nothing in the scale of time and history and geology, but the fact that I could stand there and even have this thought was a miracle.

I realized the futility of border, of this thing that we do to separate. Why do we divide ourselves by religion, and language, and color of skin? I just saw it as all ridiculous because I understood, in a very real way, that we were all made of the material of this planet, and that we will all return to the material of this planet.

So, I walked back. It turned out that I was about two weeks pregnant with my daughter, so my awakening as sort of a citizen of Earth was also my awakening as a mother. I like to think that she was there with me at this beginning and she’s been with me ever since. I've taken her with me all over the planet. She’s been to all seven continents. She’s been to the Artic and Antarctic, and her experience is unique.

So, I went back and told my then mother-in-law this story. She was like, “That’s so adventurous!” She was almost 70 and decided she wanted to check this out for herself. So she signed on the Yamal, a Russian nuclear-powered icebreaker, and went to the physical, geographic, North Pole. She said she felt it, too - that this was her planet, her rock in space - and she was so moved by it that she wrote a book about it, The North Pole. Her name is Kathan Brown and she owns Crown Point Press in San Francisco.

Richard: This story is so interesting, Camille. I know there’s a question of time, so I just want to check-in with the audience.

Camille: You guys want to go home? Should I stop? We didn’t even get to the Arctic yet.

Richard: I mean, it’s an incredible story—the ships and the Russians and all this stuff.

Camille: Yeah. So, all of this began because I gave up my seat on a plane. My grandfather told me, “Be like water.” I think he stole this from Bruce Lee. He said, “If a door opens, walk through it. There’s something there for you.” I always went the path of least resistance. I didn’t ever get hung up on this idea of having plans for my life and I've got to force myself through. I was like, “Well, that’s not working, but look, that’s open.” As I told you in that interview, the life that was given me was a thousand times richer than the one I had dreamed for myself. I know that’s scary for a lot of people to let go of that control, but it’s like Dr. Seuss with, Oh, the Places You’ll Go! It’s been magic.

Richard: At some point, when we talked earlier, you spoke - the way you put it was feeling a call To service.

Camille: Let’s talk about that.

RRichard: I was so struck by how you approached being called to service in relation to your photography. You decided you needed to learn more about photography, so you called this guy from National Geographic.

Camille: Steve McCurry.

Richard: Steve McCurry. Right. And you called Sebastião Salgado, too. For me, this is sort of stunning, like the thought of calling up Sebastião Salgado or Steve McCurry. But you said you felt called to service so powerfully that you didn’t have time to be shy, right? So, where are you today in relation to that?

Camille: So, between my mother-in-law going to the North Pole because she wanted to write a book and telling me I had to go with her to Svalbard and me walking on the ice, September 11th happened. One of the jobs I had to support myself as a homeless teenager, was as a New York City bike messenger. So, I used to deliver things to those buildings almost every day. I knew the space of that plaza in a very three-dimensional, physical way. Also, a lot of the pictures that I had of me and my friends, those buildings were always there. And when they fell, I was holding my almost two-year-old daughter watching them fall. On my refrigerator door in North Berkeley, was a photograph I’d taken of the Brooklyn Bridge with the World Trade Center behind it. No matter where I moved, this was the refrigerator picture to remind me that I was from New York. As they fell and I held her, I realized that she would never know those buildings in the way that I had, except for in a photograph or a film. So, for the first time, I understood the significance of a photograph as a historic document. It’s proof that someone or something existed.

The second part of this switch that came on, this call, was when we were bombing probably Afghanistan. It was broadcast on the news and there was like this green screen; they called it “precision bombing.” I was sitting on my couch in Berkeley saying this is so dark and so cynical. Where are the stories about how beautiful this life is and this planet is?

Literally, like a light switch being flipped, I just knew - and I can’t explain how I knew - I just knew that I was going to use my camera to document just my life. I didn’t have some grand plan. It was really just I will document the beautiful things in my own life and somehow find a way to share.

So, when that switch got activated, I was 32 years old and there was no way I was going back to school. So, I called up Steve McCurry - he’s the famous photographer of the Afghan girl with the green eyes, the most published photo in the world. I called him up. He has this incredible ability to capture something about someone using just available natural lighting. I asked, “How do you do that?”

He said, “Well, you have to come to Tibet with me.”

I said, “I will not go to bed with you, but I will go to Tibet with you.” And we went.

He was so hard on me. First, I had five different formats of cameras and this huge pelican case full of gear. He was like, “What the hell are you doing carting all this crap?” He challenged me to, “one camera, one lens, one year.” It was one of the best things I could have done as a photographer. He would pull me out of the street and say, “What are you doing in this bright light?” He’d pull me into an alley and say, “Do you see how the light is diffused?” Then he’d grab some poor Tibetan woman and sit her down. He’d say, “Do you see how her face is evenly lit?” It was lessons like that.

I called Sebastião Salgado because I wanted to know how you photograph people who are starving. What is the etiquette? I wanted to know like practical skills from him. He shoots images in such a particular way. It was nothing I wanted to emulate, but I wanted to know how he operated. So he shared that with me.

So we went with Kathan to Svalbard as a family, and this switch was on. I had my five formats of cameras and my daughter was three. We were on the bow of this beautiful, little Norwegian icebreaker called The Polar Star. We headed from open water into the drift ice, and then I realized how flawed my thinking was in Alaska because we went through 60 miles of drift ice with these huge pieces of ice banging up against the hull of the ship. It was so exhilarating. It was so wrong, this banging metal, ice-crunching sound, but I was like, “This is awesome!” Then we got to 80 degrees north, just ten degrees away from the North Pole and we hit solid pack-ice. The way the icebreaker works is it doesn’t break the ice with the front of the ship, it actually uses its weight. It pushes itself up onto the ice sheet and breaks it.

It was awesome and my mother-in-law and I were so, “If this is the Arctic, what does the Antarctic look like?” So as a thank-you we decided to take her for Christmas to Antarctica on the same little ship. My daughter was five when she saw her first penguin, but more importantly, we were in the Weddell Sea. The Weddell Sea is where Shackleton’s ship got stuck in the sea ice and then was crushed. A lot of ships don’t go in there because the ice conditions can be pretty crazy, but we had a specially stregthened ship and I saw my first iceberg.

I remember standing on the bow literally shaking, not because I was cold, but just because my brain was short-circuiting. I mean this thing was massive. It was the size of three or four Manhattan city blocks and towering out of the water almost 250 feet. They told me there was another 800 to 1,000 feet of ice under the water. So, our crazy Norwegian captain, what does he do? He goes between two of them, like this little alley, and I was like, “Oh, my God.”

On both sides there were waterfalls coming off of some of them, and I was just thinking they started out as a snowflakes on a glacier near the South Pole how many hundreds of thousands of years ago? One snowflake on top of another snowflake, year after year, how many ancestors ago is that? Can I interject another one of my grandfather’s lessons as a kid?

Richard: Yes. And maybe then we’ll just open it up.

Camille: When I was a kid about six years old I was with a bunch of my cousins and he pulled us out and made us all sit in the grass. This was on Long Island on a hot summer day, and there was just a pure blue sky. It was hot and we started to sweat. But you don’t dare question Grandpa. There was no shade anywhere and, just when we were really dripping, he points to the sky where this little white tuft of a cloud starts to appear. He says, “Do you see that? That’s your water. That’s your sweat that becomes the cloud, that becomes the rain and the snow that waters the plants, that feeds the animals.”

So when I was looking at this iceberg, I was thinking about sweat and snowflakes and time, and it was just overwhelming. That’s really when I decided to photograph them as if I were photographing my ancestors, making a portrait of them.

I have to tell you, in the 14-plus years I've been in the Arctic and Antarctic, I've never seen two icebergs that look alike or behave alike. They was really startling to me, too. They do different things with different light; they kind of glow, or just go dim, or they’re blazing white. So it’s really magic.

The way I ended up down there so much, was the work I did in Antarctica got shown to a National Geographic editor and they gave me a Geographic award. There was some money, but more importantly, it was the National Geographic stamp of approval. That led to some company asking me to come on a Russian expedition to the far side of Antarctica, which was a 30-day plus expedition on a proper icebreaker with two helicopters. We actually flew with the helicopter to the dry valleys, where most people don’t ever go, and where it hasn’t snowed in over 100,000 years in Antarctica.

We got to fly to Shackleton’s hut at Cape Royds and see how they left everything; his bed is there, his sleeping bag, his shoes, some Hershey bars. I guess Hershey was a big supporter of the expeditions in the early-1900s. It was like stepping into a time capsule. We flew to Scott’s hut with their science equipment and even the Emperor penguin they had studied was still there. It was amazing, and the smell of those places is so wonderful - this old wood and leather and time.

We took the helicopter and landed on top of the Ross Ice Shelf, which is the largest ice shelf on the planet. It’s the size of Texas, or if you’re Eurocentric, France - a thousand feet thick. I walked over to the edge to look over, and was like, “Whoa, this is crazy!” And I could see Mount Erebus, an active volcano, over to the side. I'm like, “This is awesome.” Then I realized I was standing on something that could break. I turned around and saw this bright, neon, three-inch crack and was glad to get back on the helicopter.

While I was on that expedition, there was a Russian photographer, Pavlov Echinokov, and he said, “You really should have this job.” So, I got hired, first by Russian companies, then by Norwegian companies, Canadian companies, and even a company from Monaco, to be the expedition photographer on these ships in both the Arctic and Antarctic.

Richard: Well, Camille, time flies listening to these amazing stories. It’s been an hour already. Maybe there is time for a few questions.

Camille: Ask away. He’s been very patient, he has a question.

Man in audience: Thank you for your interesting talk. I work a lot with Native people and with lots of tribal nations nature is their religion. They refer to the trees as “tree people,” animals as “animal people,” plants as “plant people” and you know, “bird people.” Instead of a superiority over all nature, it’s more equality with everything. I grew up in the Adirondacks and when I got to New York, I believed everybody was honest. I was really naïve, but I think it was a wonderful place for me to learn how to work on my fear of people and say what I think, because New Yorkers say what they think more than anywhere on the planet. They’re great teachers in that regard. Anyway, I'm mainly an environmentalist and I’d really like to hear you say something about the melting of the glaciers.

Camille: Well, when I first started going to these places, I didn’t even know what climate change was. It wasn’t until 2007, when the UN announced that it was real and happening that I started to look at my pictures and align them with my experiences and see that things were changing. Just in the few years I’ve been going, I’ve been seeing changes in both the Arctic and the Antarctic - more drastically in the Arctic, but definitely in the Antarctic as well. I’ve realized that the pictures I’ve been making show what we’re losing and what we’ve lost.

I realize I've created records. I would spend to one to three months at a time on these ships, in the most amazing parts of our planet. This beautiful solitude, the way the sound moves, and then I’d come back here and I was like, “Nobody’s getting it. Nobody’s paying attention. Nobody’s got the memo that we are in trouble.”

If we lose our poles, we lose the stability to weather in our temperate zones. So, I was lucky in that my photographs were being published a lot. I was being asked to speak a lot, and nothing was changing. Nothing was changing on a government scale fast enough. I have friends that are the head of NASA’s climate study. I have friends that work for NOAH. I have all these scientist friends who are saying, we are literally in deep doo-doo. People do not understand this is happening even faster than their models are prediction and no one is moving.

I started to feel very impotent. I started to feel like what the hell point is it to take a picture if no one is actually going to do something except go, “Oh, that’s a pretty picture. It’s so sad what’s happening.” So I stopped going and, since 2011, I’ve stopped flying almost altogether. I mean I have such status that I was always upgraded and I wore that as a badge of pride. Then I went all militant, like we have to stop doing this and this! Then I realized that’s really hard to ask this of most people who have not even glimpsed what I've glimpsed, and who have no real idea what’s coming.

Now I’ve started to do what Buddha says, “take the middle path.” I’ve learned new skills. I became a Ted Fellow, so I got to speak to a global audience. I became a Stanford Knight Fellow so I could learn how to write, how to present better on stage, how to make films. Just a few weeks ago, I went to Denali, Alaska. It’s about to celebrate it’s 100th year anniversary. This is our heritage, our birthright as Americans, and it’s in trouble. There is a great article that came out and said that if Alaska is the canary in the coal mine, about climate change, this bird is in trouble. Things are happening so quickly there, and so radically.

So, I had to figure out what my role in this is to help create new perspectives. We don’t even have a language for this integration philosophy of living in this world as if everything is integrated and alive and each one of you is related. We really need a new paradigm, a new perspective.

Man: Just to add what you said, last week I filmed a woman, Sarah James, an old woman from Alaska - a Native woman who was the leader of the Save the Alaskan Wildlife Refuge. She gave a wonderful talk that I filmed. She was saying that for years and years they would dig two feet down in the summertime, when the weather’s nice, and hit the permafrost that that was their refrigeration. Well, now they can’t do that anymore, and methane releasing is ten times worse. The polar bears can’t survive out in the islands of ice and water. So, these are big changes and they’re happening all over the world.

Camille: And we’re starting to feel them right here in California. I mean this drought is one of the worst in 1200 years they say, with no sign of abatement. This is going to be our new reality. I'm not sure people understand that. We are the last ones who will see the world as we know it. Just sit and think about that for a second. These are really the last decades of what we know as normal.

Richard: I think we’ve reached a new discussion here, an urgent one for sure.

Camille: But I want to end on a high note. Because you’re all here for a reason. You’re interested in my photography and the book and there’s something that is shifting. We see it in discussions about gender and sexuality, and now in rights for primates and rights for marine mammals. Something is shifting. We are beginning to acknowledge that we are not on the top of the pyramid, that we will not survive if we continue to act like that.

This beautiful thing that is happening, it won’t change what’s been set in motion, but it can change what happens next. I challenge you all to find the thing that you love most right now in this world, whether it’s Monarch butterflies, or polar bears, or tigers, and invest your energy in helping to preserve that.

It can be something simple like a species of flower. I don’t know. Whatever you are passionate about, if you alone did something, it would mean something and would have an effect. I think that’s the key. Put your effort into saving the thing that you love. [listening, everyone in the audience has become quiet]

Richard: If you’re okay with it, maybe people can talk to you personally. Thank you very much, Camille.

Man: Where can we find the other interview?

Richard: Conversations.org. Thank you everyone.

About the Author

Camille Seaman is an American photographer. Her dramatic and beautiful work mainly concerns the polar regions, where she captures the effects of climate change. Richard Whittaker is the founding editor of works & conversations and West Coast editor of Parabola magazine.

SUBSCRIBE NOW

TO OUR MONTHLY NEWSLETTER

Share Your Comments and Reflections on this Conversation:

On Apr 21, 2021 Ruth Block wrote:

Camille, I've seen some of your beautiful photographs from your book on Melting, and I just want to say that they mirror you and your beauty and power and sacredness. Thank you for your story, for being your courageous self, and doing and speaking out and being part of the change so desperately needed on this planet. Thank you,thank you, and thank you. You are indeed an inspiration. You are a blessing, so sending extra love and light your way in all you do.On Apr 21, 2021 Judith Phipps wrote:

This story has engaged me, inspired me, stired my creative juices. Thank you.On Apr 21, 2021 Geri deGruy wrote:

So awesome!!!!!!On Apr 21, 2021 gail wrote:

I read this with keen interest. It engaged me at various levels;especially emotionally knowing how "right" Camille is about these last few decades of seeing the world around us as it is 'now' for it won't be the same again even if we could prevent, to some degree, the degradation that is taking place on the globe.I also 'know' the interconnectedness of ALL. It is an amazing web of connectedness in which we 'live and have our being.' Charles Eisenstein's "interbeing' where if one of hurts we all hurt needs to be heard as well.

Evolution is my passion! I am not a scientist but a person in love with

The Mystery of Creation and the role evolution plays in it's enfoldment.

My dream is for all persons to somehow recognize that we come from the very

same Source and will return to that Source when we leave this planet.

Evolution could become an important part the New Story we desperately need, the new Mythic Story of Creation, as the old story of a static Universe with humanity as the pinnacle is fading or has faded into the mist of myths that no longer work for us.

I want to tell this Evolutionary story knowing as well it is only one of the many arenas of our planet that need to change.