Interviewsand Articles

A Few Early Moments

by Richard Whittaker, May 17, 2021

Lately, I’ve been reading some old issues of Parabola magazine. What treasures! Lorraine Kisley’s interview of Joseph Campbell (Spring, 1976) is an example. I wasn’t expecting to find a reference to art, but there it was. Speaking of the lack of living myth that could give us spiritual guidance, Campbell says, “I just don’t think we are going to have, in the experience of our careers, the sense of depth and spiritual dignity that the old mythologies used to give to the lives they supported and informed. We have to build our own experience of the deeper dimension of our lives – with the guidance of art. I think great art is as useful a guide to mythological dimensions as anything we have; it’s much better today than any of our churches. Many of our artists today, however, just aren’t interested in those dimensions, so even they are at sea.”

The interview took place forty-five years ago and my sense is that, sadly, his statement may be just as true today. In the early 1980s, as I was being drawn closer the art world, I was disturbed to feel the lack of sustenance in the art often getting the most attention. One day a description in Artweek about the meaning of art bothered me so much I decided to do some investigation of my own. What did ordinary people think about the meaning of art?

I purchased a Sony Walkman and a microphone and began asking friends, “What is art?” Soon I felt bold enough to go to the Oakland Museum where I asked visitors and docents.

Point blank, it's an impossible question, but I wanted to see what people would come up with. My few weeks of pursuing this were a revelation. One docent, in high dudgeon, snapped that, “Any schoolchild knows what art is!” She was unwilling to enlarge on that in any way, and angry that I should ask such an apparently dumb question. But in nearly every other case, whomever I approached - microphone in hand - gave it an earnest try. It was amazing to experience the sincerity with which strangers responded, never mind my discovery of the power of holding out a microphone.

At a certain point, I realized the language in response to this question about art inclined strongly toward the spiritual. Art was something “from the heart.” It was “about truth,” “love,” “beauty,” “transformation,” “transcendence.” Why did these things seem missing in art world discourse?

When I realized people were speaking with such innocence in spiritual ways about the meaning of art, I began to experiment. I’d remark, “What you say sounds like a spiritual thing.” To this, there was always ready agreement. But if instead, I said, “What you say makes me think of religion,” there was always an objection.

This was both striking and touching.

Mine was a short investigation, but it was hard not to conclude that art remains a territory – as Campbell believed - where the spiritual was still alive. So why wasn't I feeling this in so much of the sophisticated art I found being held up for high regard?

New Topographics

William Jenkins’ influential photography exhibit “New Topographics” in 1975 might have seemed strange to many of the people I spoke with in my informal survey. The photos in that exhibit are characterized in a Wikipedia article as: "stripped of any artistic frills and reduced to an essentially topographic state, conveying substantial amounts of visual information but eschewing entirely the aspects of beauty, emotion and opinion." More can be said.

The work of eight Americans and two Europeans shown at the International Museum of Photography at the George Eastman House in Rochester, NY, for many viewers, might have satisfied a premise I’d heard the late Van Deren Coke declaim at an intimate gathering of aspiring photographers one evening in Berkeley, CA. We’d all had a glass or two of wine and the guest of honor, SFMOMA’s curator of photography, was feeling good. Surrounded by aspiring young photographers and, having talked at length, it must have seemed time to wrap it up. And so he paused and, with everyone’s attention focused, delivered the bottom line: If it doesn’t shock, it’s not art!

It was a shock hearing his proclamation. By then it already sounded old hat, and summarizing art in this way made me angry. This idea is always connected with some form of violence. Virtually never would the silent opening of a window in our wall of associations that lifts one's heart be thought of as a shock. We speak of that rare event as magic, or even the miraculous.

New Topographics was an exhibit that Van Deren Coke must have appreciated. For those schooled in the art world’s alignment with postmodern discourse, the collection of photographs signaled a way forward. As landscapes, nature's presence in the background showed our loss of connection with it. Foregrounded were the unprivileged doings of contemporary life - parking lots, service stations and so on. Life marched on unconsciously and, one might be tempted to say, without real meaning. This is the situation, the photos seemed to say. What do you make of it?

It was a powerful exhibit in the way it threw down a challenge. What was to be taken from the display of the photos of Lewis Baltz, for instance? That the camera's best use was now as a scientific tool of the double-blind study?

But nature was still there. Light was still there. Even beauty, stripped down, was there - and an artful formalism in many of the images. And whatever else might be said, the exhibit set a new standard. The landscape could no longer be presented in innocence. From that point on, aspiring photographers began imitating "the new topographics."

In the Context of What?

A second encounter in the early 1980s, perhaps a year later, underlined what I'd experienced in my evening with Van Deren Coke.

I’d enrolled in a photography workshop in Carmel, CA led by William Jenkins. Although, there was a description of who he was in the Friends of Photography’s workshop prospectus, I didn’t know anything about him. Eight or ten others showed up at our first meeting at Asilomar in Pacific Grove, California. Each of us, in earnest hope, brought a portfolio of our work for Jenkins’ review, and were curious to get another take on the current climate of art photography from one of the most influential insiders of that time.

I should add that I hadn’t gone to art school and had never had an ambition to be a photographer. It had entered my life - and in a powerful way – by accident rather than design. When I showed Jenkins my portfolio, he seemed surprised for a moment and then declared that I belonged in advertising, not the art world. And looking back, had I been so moved, I expect I could have made a career in that world of dark arts.

In any case, I’d paid my money and so I suffered through the next few days. Besides, Ansel Adams himself - the founder of the Friends of Photography - was still showing up at these workshops. Several times I was present as he chatted with us informally. His unfailing graciousness stands out in memory for, as usual with random groups, there were always remarks and questions that begged for a slap on the head. It was something he never allowed himself.

In our workshop on the second day an older photographer – beginning to get a feeling for where the wind was blowing - asked Jenkins, with some indignation, why there seemed to be no place for beauty in the photography being held up to high regard.

This energized Jenkins. Here was a naïf who badly needed some education. He explained that art was, first of all, tied to context. “If a tennis shoe is hung on the wall of a museum gallery, it’s art. Anything hung on the wall in a museum is art simply from being there.”

Maybe there are two kinds of teachers. Some hammer the student "for their own good" and others take a more sensitive approach. It's hard to forget the satisfaction Jenkins took in delivering the news. Again, I have to admit, I found myself feeling angry. And it was easy to see that three or four others in the workshop were sympathetic with their older comrade.

The debate that followed was not long-lived, and those siding with the older man were quickly reduced to silence. I kept my mouth shut lacking the self-confidence to enter the ring. But I was not about to abandon my faith in the direct experience of something that the older photographer would understand. At the same time, the voice of beauty now sung off-key having being forced to vouch for an endless parade of commodities.

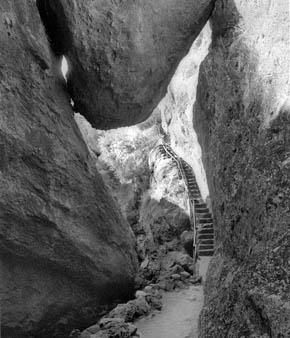

In the next several years I continued taking photographs and wrestled with how to move forward. Along the way, as I ran across them, I collected quotations about art that touched me. Here are a few favorites with some photos of my own:

Joseph Bueys in 1979:

“Creativity isn’t the monopoly of artists, this is the crucial fact I’ve come to realize, and this broader concept of creativity is my concept of art…The dilemma of museums and other cultural institutions stems from the fact that culture is such an isolated field, and that art is even more isolated; an ivory tower in the field of culture surrounded first by the whole complex of culture and education, and then by the media which are also part of culture. We have a restricted idea of culture which debases everything…”

Jay De Feo— On her painting The Annunciation—letter, J. Patrick Lannon, 1959 - “I painted this kind of winged vision that announces, in my eyes, or promises some realization of all that is good in this existence, and more specifically it is a promise to me of the realization of certain powers creatively when I make some association between the words creative and spiritual or divine. At least, I feel this way when I am doing my best… I only have occasional moments of understanding and awareness of the matter when I see what I have painted in a moment of objectivity.”

Jacob Needleman - On the potential of art - interview

“I think what we are talking about is, what is a salvational influence in society? What can help? It always starts with a small group. There are films sometimes that really touch something, books which sometimes touch something, that help people, give them hope. I think what art can do is give hope. Real hope.”

Henry Miller Rosy Crucifixion, Book One, Sexus -

Every day we slaughter our finest impulses. That is why we get a heart-ache when we read those lines written by the hand of a master and recognize them as our own, as the tender shoots which we stifled because we lacked the faith to believe in our own powers, our own criterion of truth and beauty. Every man, when he gets quiet, when he becomes desperately honest about himself, is capable of uttering profound truths. We all derive from the same source. There is no mystery about the origin of things. We are all part of creation, all kings, all poets, all musicians; we have only to open up, only to discover what is already there. What happened to me in writing about Joey and Tony was tantamount to revelation. It was revealed to me that I could say what I wanted to say- if I thought of nothing else, if I concentrated upon that exclusively- and if I were willing to bear the consequences which a pure act always involves.

Louise Nevelson

“You see, I think we have measurements in our bodies. Measurements in our eyes. Look, dear, we walk on two feet. So we’re vertical. All these things are within the being: weight and measure and color. And if the work is good work, it is built on these laws and principles that we have within ourselves.”

Jane Rosen: (interview 1996, The Secret Alameda #8)

“I want to make work that you don't have to have a Master’s degree in Art History to understand. When I lived in St. Martin there was something about the quiet and the water. I became interested in fishing and met an elegant old black man, Mr. Anstley Yarde, who was very tall and thin, with a great presence. He taught me how to fish. You use a can and string. He’d get me at six o’clock in the morning and we’d get these snails. We’d sit on a rock and drop soda-can lines and just sit there. I never caught a fish but he’d catch them. He’d hear them, and I thought, this man has knowledge. And one day, we’re sitting on the rock and he asked me what kind of art I made. I knew Mr. Anstley Yarde would not understand the art I was making at that time and I realized I wanted him to understand it.”

Soetsu Yanagi – from The Unknown Craftsman

“One can not replace the function of seeing with the function of knowing.”

About the Author

Richard Whittaker is the founding editor of works & conversations and West Coast editor of Parabola magazine.

SUBSCRIBE NOW

TO OUR MONTHLY NEWSLETTER

Share Your Comments and Reflections on this Conversation:

On Sep 17, 2021 Gayathri wrote:

Thank you for these musings and these 'art-quote' pairings, Richard. A light burns in me, of re-cognition, inspiration, sweet hope and wonder.On Sep 16, 2021 elza wrote:

Stunning Pictures and such a wise way of seeing and sharing things words can say about artOn Sep 10, 2021 Ruth Block wrote:

This article was worth revisiting again with your photos, which always hold such compelling mystery and magic, inviting my participation. What good art does, for me, as I can only speak for myself, is invite me in to participate, creating a dialogue of sorts where something changes; one walks away taking a feeling of validation of one's own experience, or a knowing from a different perspective. If its good art, its a gift you get to take home inside of yourself, something wonder-full. Thank you, Richard, once more for speaking your mind and sharing your various arts with us.On Sep 9, 2021 Carol Beth Icard wrote:

Thank you for this. Reading about your investigations and seeing your photographs paired with wonderful quotes has been a real gift in my day.On Sep 9, 2021 Nancy Ingwersen wrote:

Gratitude.On Sep 9, 2021 Kristin Pedemonti wrote:

Thank you for bringing varying perspectives through quotes and through your own courage and curiosity to ask questions. I've often found the art world to feel pompous and like a cool clique that speaks in code. To me art is that which makes us think, see differently, see beauty, or pain or hope or love or a story or feel something. It can be complex or simple. And yes, it somehow transcends the ordinary.On Sep 9, 2021 Carol Messinger wrote:

Thank you. The article helped me put some nervous musings into perspective. I especially appreciated the Henry Miller quote.