Interviewsand Articles

A Visit With John Abduljaami

by Richard Whittaker, Apr 2, 2007

Early last December I found a message on my voice-mail from artist Mark Bulwinkle, “Would you like to go see John today?” He was talking about Oakland sculptor John Abduljaami.

Over the years I’d seen examples of Abduljaami’s carved wood sculptures in Bulwinkle’s own studio and in Marcia Donahue’s home and garden in Berkeley. Both, I knew, were great admirers of his work.

A few hours later, Mark and I were heading down West Grand towards the sculptor’s open air studio in West Oakland, an older part of the city that includes a mix of industrial, commercial and residential buildings. It also includes the Port of Oakland with all the rail and trucking operations for distributing the huge volume of freight handled by the port. The old residential neighborhoods of wood frame houses that remain are populated, mostly, by African Americans, although this is changing. It's the part of town where sections of the Nimitz freeway collapsed in the Loma Prieta earthquake in 1989, an event that has permanently changed the area. The disruption caused by new freeway routing and other factors, initiated a spiral of redevelopment in which increasing prices are driving low-income families out of the area.

Nowadays, whenever I find myself in West Oakland, it’s usually because I’m visiting an artist. Years earlier, I’d often be driving down West 7th street towards my wife’s garment business which was housed in Oakland’s old brick Firehouse No. 3. Right next door, in another converted commercial building, the glass artist John Lewis had his studio and home. The two buildings shared an area at the rear where I’d often watch Lewis loading his glass furnace or sitting at his bench shaping the molten glass into one of his famous moon bottles.

As happens in similar areas of other cities, artists had moved in, attracted by the low price of housing and studio space. Bulwinkle has lived in West Oakland for well over twenty years.

Still, a trip to West Oakland always brought me some uneasiness. I remembered occasions when one of my wife’s employees was mugged on his or her way to work, and it was always unsettling to witness the evidence of unemployment and other hardships endemic to the neighborhood.

These things bothered Mark, too. Once, in talking about Abduljaami, he'd remarked, “To hear the story of John’s life is to learn about the story of Oakland—and my neighbors—and what happened to them. It's the same in any large American city, particularly coastal cities—what happened to African Americans all the way up to today. They came up from the south and now they are just getting pushed the fuck out of here."  He went on, "Nobody tells that story, but that’s what I see. Where are they going? I think if you asked Angela Davis, she'd tell you they’re going to jail. I don’t know that, but California is building a lot of prisons. Some of my neighbors participate in general culture, but man!, a lot of them are left out!”

He went on, "Nobody tells that story, but that’s what I see. Where are they going? I think if you asked Angela Davis, she'd tell you they’re going to jail. I don’t know that, but California is building a lot of prisons. Some of my neighbors participate in general culture, but man!, a lot of them are left out!”

There was something else that bothered Bulwinkle. In all his years of living in a black neighborhood, he’d had a great deal of time to watch his neighbors. As he put it, “They're constantly inventing art.”

He’d watch kids playing in the street and see the living process of creation of which the larger culture has been the beneficiary. “One of the main creative forces in America, and maybe in the world, has been the African American,” Bulwinkle mused. “But then, the dominant culture comes along and, sadly, they steal it. They dilute it; they bastardize it and commercialize it, and turn it into drivel. But my neighbors just keep on inventing.”

Certainly Abduljaami is a singular embodiment of the creative drive. He continues working year after year without a dealer or gallery representation, and without concern about the art world in general.

“John is his own man,” as Mark puts it, “Can you imagine what the students at some university might get out of watching him? I just don’t have a lot of faith in what’s going on today. Everything just seems to be incredibly academic. Watching John would be to see a human being create something brand new. Any artist is like that. They give birth to something. It comes out of them, and you don’t know how it happens.”

Mark Bulwinkle's Studio

Pulling up in front of Abduljaami’s place, he’s nowhere to be seen. It turns out he’d left that morning for Detroit. Mark had warned me that we might miss him. It had started to rain, and so we returned to Mark’s studio. I followed him into his small kitchen where everything had been painted over with figures, faces, words, designs; there were unexpected objects in all directions..jpg) It was the site of an art blitz, an exuberant overflow of expression, the giving in to it, something that any artist who has ever experienced it will easily recognize, the joy of that energy finding its way into form. Kitchen, bathroom, bedroom, office, all of his living areas were simply different chapters in the same story.

It was the site of an art blitz, an exuberant overflow of expression, the giving in to it, something that any artist who has ever experienced it will easily recognize, the joy of that energy finding its way into form. Kitchen, bathroom, bedroom, office, all of his living areas were simply different chapters in the same story.

But today, his mood was more reflective. “What kind of culture would we have in America if it wasn’t for the African-American?” he asked rhetorically. "Look at popular culture. What the fuck would we have going on, German folk dancing? And modern art has a tremendous debt to African art, which I don’t know if they even thought of as ‘art’ in Africa. It was much more a part of their whole life. I think that’s why they could part with it so easily. ‘Yeah, I’ll sell you this for a few bucks,’ and it would end up in Matisse’s studio! Because they could just make more of it!”

Meeting Abduljaami

A couple of weeks later, Abduljaami had returned and Mark and I drove over to see him. The artist worked in an area behind a chain link fence that had once been the parking lot for an old industrial plant for producing oxygen, of all things. That explained the steel tanks, pipes and the odd structure of some of the buildings on the site. The current owner of the property, Paul Discoe, a builder/designer specializing in traditional Japanese joinery, is a fan of Abduljaami’s work and makes the space available to him at no cost. Discoe also contributes material—timbers and portions of whole tree trunks unsuitable for his own projects—for John to use as he wishes.

Out in front on the sidewalk stood a carved wooden elephant maybe seven or eight feet high next to a couple of ten-foot long painted alligators. Behind the fence were dozens of other carved wooden figures.

Mark and I walked into the open yard where John put his chain saw down and greeted us. He had been at work on a huge section of log which he was turning into a cow. Looking at it, I could see that the ears had been roughed out, but I couldn’t figure out how he was going to make the front part of the cow’s head. There didn’t seem to be room for it. As Mark once told me, often he’d see John working on a piece and think, “Man, I don’t know how he’s going to work that out!” But inevitably Abduljaami would pull it off leaving Bulwinkle marveling at his sheer formal ingenuity.

Abduljaami was obviously pleased to see Mark—they were old friends—and he extended a friendly hand towards me. I couldn’t help noticing the sawdust from his chainsaw stuck in the wool of his watch cap, his eyebrows and beard.

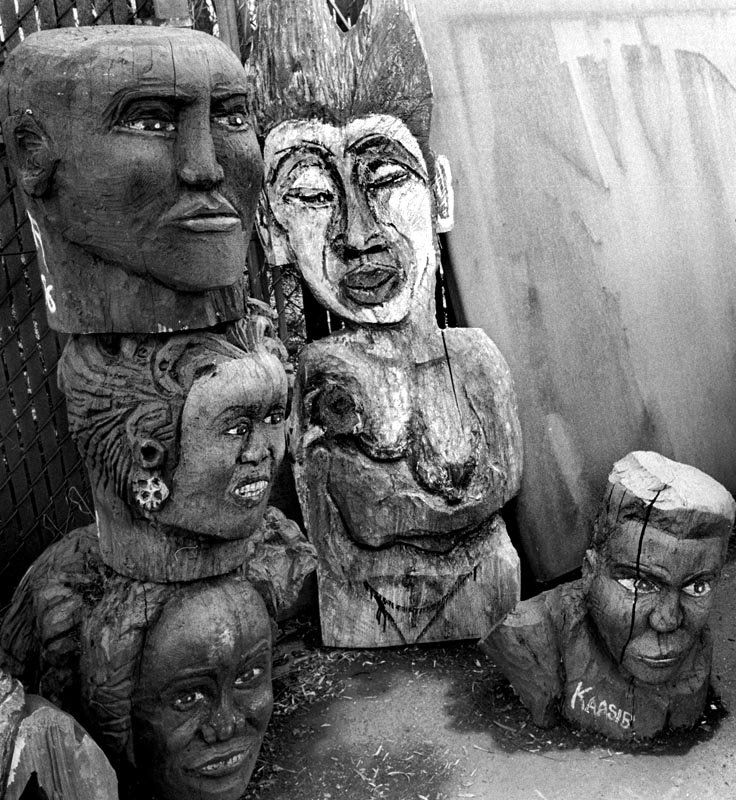

While he and Mark chatted, I wandered among a collection of carved sculptures in various states of finish unlike any I’d seen in one place before: carved dogs, apes, turtles, monkeys, horses, birds, and compound pieces of two or more figures—a cowboy on a rearing horse, two apes intertwined, and others. There were two throne-like chairs with bas relief portraits, a coffee table with a round glass top supported on the legs of a huge, cartoonish purple spider, multiple human figures, busts, even a clasped fist and arm. There were other pieces, too, which crossed into abstraction. No order was apparent in this creative overflow other than the simple imperative: make room for the next one.

Wandering happily among these carvings, camera in hand, I was attracted to a carved head which evoked something of Guernica. “It’s a dragon,” Abduljaami told me. It had been a larger piece which had fallen and cracked while he was working on it. Unwilling to complete the piece with a crack through it, he'd simply cut the head off. “There’s the body, over there,” he said, pointing. Another piece I spent time with was a black angel. It appeared to be a self-portrait.

Mark, I knew, owned another of Abduljaami’s self-portraits, a piece with a kind of quiet dignity which I’d noticed sitting on one of his work benches. He’d also showed me a carved figure of a woman about seven feet high. “That’s John’s wife,” he told me. “Look at the expression of her face.” The piece demonstrated one of the things Mark admired most about Abduljaami’s work. “It’s heartfelt. You feel what he’s feeling. Anybody who really sees this stuff has to feel that. That’s why his pieces work so well when they’re separated, say in an exhibition space. You can see the shape of it, the beauty of it. It’s stunning.”

Talking with Paul Discoe, I’d learned that originally Abduljaami had used only an ax for his carvings, and that he was very particular about the wood he used, only black walnut, a very hard wood and difficult to work with. I’d mentioned this to Mark who told me it was true. He went on to describe an ax he’d fashioned for Abduljaami over twenty years earlier, “just a regular double-bladed ax, but I took one side and shaped a much sharper curve [gesturing]. I tempered it and sharpened it. But over the years John’s loosened up. Now he uses anything that comes his way, even chunks of palm tree.”

Before we'd arrived, Abduljaami had been at work with a chainsaw as the wood chips in his hat attested. Talking with Mark later in that day, I mentioned the chainsaw and my inevitable association with the roadside attractions popular in Northern California: redwood bears.

Maybe I’m imaging it, but it seemed I saw a flash of outrage, but whatever passed across his face, he quickly recovered. “Well, it’s the difference between a craftsman working and an artist working. There’s something else going on in that man’s mind which he's going to reveal to us.”

Folk Artist

Six or seven years ago I remember wandering around in Bulwinkle’s half-acre lot among hundreds of his steel sculptures. On one piece, painted along the edges of a figure, I noticed the words “I am not a folk.” Although Bulwinkle’s work often exhibits an aggressive, confrontational edge as well as a sophisticated sense of design, to the careless or uninformed viewer his work can appear untutored. Moreover, his work possesses the direct force one often feels in folk or outsider art. It might be a good time, I thought, to broach this subject.

He paused before responding, “If someone refers to me as ‘a folk artist’—and they have over the years—I ask, ‘Does that mean I’m a folk? As opposed to what…?’”

His objections boil down to one simple point. Such work is not accorded the same degree of respect as the more fashionable work that finds its way into the major museums and galleries. This is reflected not only in the lower prices, but in the smaller amount of text such work generates on the part of critics and curators, not that there aren’t some significant exceptions to be found. Folk art, the best of it, Bulwinkle readily agrees, can be “real art.” And that’s the measure: Is it real?

Mark recalled how a friend had come by and talked about his temptation to buy a drawing from one of the better-known Bay Area artists. It was priced at $14.000. Mark's friend had decided against it, albeit reluctantly. After further talk, the friend bought a piece of Mark’s work for well under $1000 and was quite pleased with it. The whole transaction rankled, however, because what were the factors accounting for the great difference in prices between the work of the two artists? Did it have anything to do with the intrinsic qualities of the work itself?

But getting back to Bulwinkle’s gambit. “Am I a folk? Mark has an MFA from the San Francisco Art Institute. Coming to mind suddenly is Kris Kristofferson. Who would guess that the song, “Me and Bobby McGee,” made famous by Janice Joplin, was written by a Rhodes Scholar? A lot of people probably thought Kristofferson was some kind of folk.

Ever since I first heard it, the term “outsider artist” has rubbed me the wrong way. I don't recall coming across its logical opposite, as in "who’s your favorite insider artist?”

On the other hand, the impulse to categorize is understandable. There's a bewildering variety of things called "art" today. A lot of it requires a good bit of explanation in order to have a clue. But you don't have to have an MFA, to appreciate Abduljaami's ten-foot long, painted alligators—or any of his other fanciful creations.

Mark told me that Abduljaami was brought inside once. That is, in the mid-seventies, some of his work was included in a figurative sculpture show at SF's Paula Anglim Gallery that included the work of Robert Arneson and Viola Frey. As Mark related, Thomas Albright, the most influential Bay Area critic of that era, was a fan of Abduljaami’s work. He wrote about it admiringly in the San Francisco Chronicle. And for awhile, Abduljaami found himself "an insider."

But it didn't last. As Mark relates, John put it this way, ‘What happened is that Thomas Albright died. He’d been in my corner, and he died.” But Phil Linhares of the Oakland Museum keeps an eye on him and is responsible for adding a couple of Abduljaami’s pieces to the museum’s permanent collection.

Over the years, Mark has heard many of the artist's stories. "I know a lot about John’s life, and it’s a tough life.” There was more than a little hardship; there was time in prison, and when he got out, he found a job shoveling grain out of a boat in Louisiana. When he nearly got buried alive in the hold by a huge spill of from above, he decided he was never going to work again. “I think that’s when he started seriously carving wood,” Mark told me. “He set out to be an artist, and he became one.”

.jpg)

Postscript

A couple of weeks later I got an email from Mark. “Was over at John’s today. He’s started on a figure of Malcolm X.”

A few days later I got another note, “Saw John today. Malcolm was all undercoated white. I suggested Malcolm might not like that. We laughed. This piece should look good.”

Then a few days later Mark wrote, “The piece is finished. It’s fuckin’ incredible!”

On a later visit, Abduljaami shared a few things with me. He showed me the first piece he'd ever carved. He was eleven years old at the time. One of his jobs had been cutting firewood for his family. It occurred to him that he could make the task less of a burden by taking some time to carve something interesting just for himself. He realized suddenly that his mother’s heaviest cutting knife would be just the right tool. “And it was!” he said.

While carefully at work on this first carving, he didn’t notice that his sister had been watching, and had run off to tattle. “I’ve kept that first piece. There it is, over there,” he pointed. “You know, that was before child abuse laws,”

He’d gotten quite a whipping for his first effort. It had stopped him for a number of years, but he’d tasted something so special with that first carving that later on it became his life’s work.

John Abduljaami continues to make whatever he pleases, sometimes just for the challenge of it, but mostly because it opens a window on deeper places, and it's work that can speak to anyone. ∆

About the Author

Richard Whittaker is the founding editor of works & conversations and West Coast editor of Parabola magazine.

SUBSCRIBE NOW

TO OUR MONTHLY NEWSLETTER

Share Your Comments and Reflections on this Conversation: