Interviewsand Articles

Interview with Julian White

by Jan Boyer, Feb 19, 1999

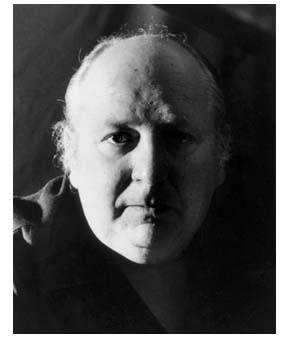

For some thirty years, Julian White was actively associated with the human potential movement in America. He presented seminars throughout the country on the connection between music and self-knowledge. The Jungian Society and Association for Humanistic Psychology often sponsored his lectures and demonstrations. He appeared in programs with Joseph Campbell and the poet Robert Bly. Mr. White, formerly a professor of Music at California State University in Hayward, Mills College, Oakland, and Dominican College in San Rafael, taught piano and composition in his studio in Kensington and was an active concert pianist and composer.

Jan Boyer: You've told me about your heritage, that you worked with Egon Petri, and so forth. How did you come to be composing, performing, and teaching?

Julian White: I could tell you that I graduated from Juilliard, but most of it was wasted on me. I was studying with teachers who I wasn't really ready to study with, teachers who made me feel inferior. So it was great luck to come across my last teacher, Egon Petri, who was the healing teacher. His background was with Liszt, Busoni, and there was a connection with Brahms also.

He actually gave me very little technical knowledge, but the thing that made him the healing teacher was that as I walked through his door coming for a lesson, the questions I had all evaporated. He basically said, without actually putting it in words, "you could use me in a pinch, but you have the capacity to figure all this stuff out yourself." When we first met he said, "I think we'll work out just fine because you came on time, I see that you have a car out there, and I'm going to teach you how to prepare my favorite drink." I passed that test and after that I was his student and I learned, not necessarily the core of the musical message, but he gave me an inkling as to its aura.

There was another time of great luck when I was very young. I remember walking to school and, without even knowing what the words really meant, I said, "I'm living in hell, I'm living in hell." And the thought came that I'd better be very, very careful so that I didn't step on a frog. To be very, very alert and to memorize before the event, what I would say to a frog if I deliberately didn't step on it, and in case it said it would grant me three wishes. Because in moments like that, in such extreme excitement, you might tend to forget your real agenda. So as I was walking to school I remember practicing my response. It was rather vigorous. It was, "You can take two of the three wishes and do whatever you want with them! But my real wish is that you teach me how to practice!" ... This, coming from a seven-year-old.

Everybody wants to do it right, and if there is no instruction, if there is no key as to how the thing opens up, then you're left to, in a way, eat yourself up. "Here's your assignment, study this, bring this back next week, learn this"....well, that's easy to say, but how about the tools?

JB: It's like being a Christian, in a way. They say, "be good", but they don't often instruct you about the "how"- how to practice that.

JW: That's right. I'd say that of all the different traits, of all the different manly traits, I probably will be judged to be weak in the trait of courage or fortitude because I owe almost all of my illuminations to my pupils. It's easy to see how things work when I'm not the central character. So the gradual evolution has been many things. One primary thing is that the music I study, and that I teach, and that I write, is not an entertainment, but a piece of knowledge. It stands for important stuff. In some other culture, a person would study calligraphy, or tea ceremony, or flower arranging in order to use, through that metaphor, an observable welcoming to the spirit.

JB: The spirit? The musician's spirit?

JW: No, just the spirit of the Human. I don't see anything special about the musician's spirit, or the hairdresser's spirit or the shoe cobbler's spirit. How do you see your life? What holds the event still enough so that you can see it? What do you do that is evolving from small pieces into larger pieces? What tangible thing can come from something so elusive as a thought or an impression? I feel that we're all very lucky when we study, say, music. It's a thinly disguised metaphor.

We have language, which is a very thinly disguised metaphor for the transmission of feeling zones. I don't see that language's main function is to provide data; but you provide the distance in order to see something. It's like the piece of cloth that washes the mirror so that you can see something. All this comes available through practice. And all this comes available through a serious look at what you're doing.

JB: You mention that music is a metaphor.

JW: You might ask, how can anything be learned? I think that we somehow have to have access to what we have, or what we essentially are, or what we could be, or what our connection to a larger picture is. We have to have access to that. In order to have access to one's self. We need some tool.

It's always been that way. There is an apocryphal story about a culture that was extremely sophisticated, beyond war, beyond terrible acts. Because of their richness they were easy prey to the barbarians, and they knew that in the next attack, everything tangible was going to be destroyed. So as fast as they could, they tried to teach everything they knew into dance movements. So, if you want to transmit something, and all your books are going to be burned, your films...if all that stuff is going to be burned, what will be left alone is something that looks like entertainment.

So some traditional dances may transmit ideas and certain symmetries of thought and act on a very high plane. The same thing happened with the end of the Trojan Wars. The Greeks built this big horse, and the horse was so big and wide that it couldn't possibly go through the gates, the wall around Troy. You know that they had soldiers inside the horse. So this was after many, many years of being engaged in battle, of a siege on the city. The elders woke up one morning and there was this beautiful thing outside the gate. They got together, and one person said, " Well, we certainly deserve that trophy of war, they had the sense to pay respects". Another said, "It certainly is a tribute to the fact that we like horses". They kept looking and looking at it, essentially wanting to have it, but they couldn't have it because it was outside the gate, and there were too many things that were threatening. Like maybe it was a trap or something.

And then one guy said, "Well, I think it's just a work of art." At which time they carefully put wheels on this thing, tore down the wall, and....

The story says that the work of art can look very innocent, but it can go very, very fast to the psyche-very fast to that part of us that is pre-language.

JB: You've spoken of serious practice as a way of opening the mystery or the package. You've talked about drill and repetition...

JW: Practicing is a metaphor about working with the unknown. What is your capacity for ambiguity? How fear-ridden is your whole being so that you have to mess up the stuff in order to get a handle on how to work on it? As a pianist, it's not finding a note, pressing it, or digging at it, provoking it with the end of one's finger. That's not music. That's nothing. All the notes and their different combinations are reflections of things that we know, on an obvious level, and on a hidden level.

JB: Are they reflections of that, a transmission of that, in a way?

JW: Let's say somebody did you in, and you're really unhappy. Your voice is going to take on a certain quality of sound- the music will have a certain shape. It will certainly not go uphill, because your whole being has just been drained out of your chest. [Sighs heavily] Ohhhh, Jesus. [Voice drops]. It's not: da, da, dup! [voice rises]. That means you're getting out of bed in the morning! These are all tried and true reproductions, almost pure xeroxes, of human experiences. And they're all done over long periods of time by humans. These are all things that we know. And what do we know? We're stuck in grotesque bodies, on a planet that has some kind of gravity, and everything is designed to distract us, and to help us forget what our real home is.

Nobody can tell you what this home is. You find the home through the tool that you really like, the metaphor. It doesn't have to be the metaphor of classical music. It could be the metaphor of cuisine, the metaphor of where you put your table, or how you put a flower in your little glass. What is the quality of how you are touching yourself? So, if that gets refined, I feel that gradually there comes a moment, if you're lucky, where you can lean against life and feel cozy. Instead of always being on the run.

JB: So this could be coming into being either by actually creating the forms of the music on paper, the notes, or by performing something that's already been written, this quality of touching one's own being, or of touching one's self, as you said.

JW: That's right. It's all the same.

JB: Listening, too?

JW: Absolutely.

JB: This reminds me of the phrase, "Encouragement to keep looking and to join in the Great Work," you wrote in the program notes to the Five Parables you composed for the Berkeley Community Chorus and Orchestra which was premiered in 1992. Is this what you're referring to when you're talking of this work?

JW: It could be. But let me respond to something else. Somebody, let's just say, for example, Ludwig Beethoven, has some kind of urge, or need that maybe translates into some kind of shape, some kind of possible access to some door. Gradually, that need, that imperative, finds its way into notes. It's no different than when you're walking around without a thought in your head, when something is triggered off, which is before language and then, if you stay with it, it might just take a hundredth of a second, and before you know it you're saying something to your friend that you're walking with.

So here's Beethoven and he is responding to some need that he has. Not a need to write a piece with four sharps, nothing as stupid as that. He has to say something; he wants to clarify a state that he's in. When things don't go well, you always know it. Some people are tuned in to "Gee, thing's are not going well "I think it's time to make a new casserole," or "It's time for me to draw some pictures for kids."

So in order to set his moment correctly, he'll write something. And he'll use all his skill. Not only to write, but to leave evidence of what he really has in mind. Because a piece of music is not "Go three blocks and turn right at the Chevron station". It's not as gross as that; it's very, very subtle.

So, Beethoven dies. His music is preserved in different publishing houses. And then somebody feels a kinship with that piece of music and starts to join Beethoven in the process, backwards like "how do you decipher the whole thing?" And then interesting things come in, really terrifically interesting things. What's one's relationship to information that is not going to be blocked by one's narcissistic tendencies?

JB: How open is one, in other words, to what's there?

JW: Am I playing Joe Schlump or am I playing Beethoven? And what is there in my understanding that matches Beethoven's understanding? And then all the problems of the craft: how loyal are you, how faithful to the craft? We've talked about this in lessons. How strong is the fear that forces you, the second you arrive at the campsite, to go around peeing on all the trees? All this is information.

All these metaphors are like hammocks. The hammock is stretched between two objects that hopefully are secure. The doorway to the studio has a tremendous number of cobwebs, and inside the cobwebs there are things....Do you know what a chrysalis is?

JB: A cocoon where there is a new life metamorphosing inside?

JW: Right. Like we're living in a chrysalis, and all these different things, all these different forms that we take as our metaphor, or as our standard bearer, or as our looking glass-all these things have a possibility to serve us.

JB: You have used the example, even, of something like tempo. You've said, if you play something too fast, too flamboyantly, it's like you are blowing your own horn, and if you play too slowly, it's like you're bludgeoning the audience with every note as if they were dummies.

JW: And everybody knows about it. You go to an opera, and somebody finishes his or her aria, their solo song, and there's nothing but cheers and cheers. Another part of the opera, somebody else sings. The second they get through singing the whole audience starts coughing, not because there's a sudden influx of some viral material, but because the person who was singing wasn't using a relaxed function of the singing apparatus.

Speed stands for things. I may have mentioned to you a study in New York of who gets mugged. They set up cameras in one of the worst places and got a wide selection of people to traverse this gauntlet: old people, young people, cripples, people walking slow, walking fast. And it turns out it has nothing to do with age, nothing to do with health or infirmity. It had to do with the rhythm of the walking. You get someone who is ninety, who walks evenly -you stay away from that person.

That was a study of human beings. Then finally the United States Navy accepted that study and instructed their sailors that when you are in shark-infested waters, swim evenly, even if you're dying inside. Regularity is a signature for health. All this comes in on a subliminal level.

JB: Your mind doesn't know it.

JW: That's right. You can't talk about it. But it's there.

JB: Some of us are interested in studying the effects on our feeling, thinking, sensing and moving of certain forms of sound. You're saying that there are universal responses to certain forms, to certain rhythms, certain tempos.

JW: I think so. Absolutely. It's equated with certain patterns of experience. It would be like if you're given three, four words in your acting class. You can't be too weird about it, but can you make this sound like you don't really know what you're talking about? Can you make it sound like you wish the other person really wouldn't say something? Can you make it sound like it's a real question? Can you make it sound like you don't care? These are subtle differences. But it is just a way of saying that beyond the note there is meaning.

JB: So that even one note could be received quite differently--

JW: One note would be hard, but so much is understood in retrospect in music, or in language. You get all through with a sentence or a paragraph and then say, "oh yeah, I see what is meant now by the first word". So let's say we have a song that starts out with one note. As it's happening, you have no idea what that's going to be like, but maybe after ten or twenty notes, it's the first note that defines the character, in retrospect.

JB: In context.

JW: It's understood in the context of more material, because you need an abundance in order to mimic the way the natural world is set up. It's a great time of the year; you drive by trees and every sixteenth of an inch is covered with some kind of bud or flower; the whole tree is nothing but an exercise in nature's redundancy, nature's abundance.

The same thing in a piece of music. You could almost define the different periods of music according to the amount of redundancy, and the extent to which people love redundancy. A perfect example would be early classical music [sings a phrase]. Let's say you were scratching yourself and you really didn't quite hear that. Don't fret. Here it is again in the violins: "dee dee dee dee-tee dee. Oh, somebody just stepped on your foot. Don't worry, no, no- we'll do it again- maybe a variation: da da da da-ta da.

And then you could say, well what kind of music would be designed for what kind of listener? Music, any art form, any metaphor, has to be bite-sized. So then you get closer to the twentieth century where there is less redundancy. It's like, "I want you to really participate. I broke my buns writing this thing, the least you could do is sit there and hear it." So you're going to get it once: bit boing da da duh, bit wee ditty: whatever the thing is. It could be as weird as you want it. It's a different expectation.

JB: And that happens in nature, too.

JW: Sure. I'm sure there are some places where the environment is unbelievably stark.

JB: Things just happen once.

JW: Happen once. And that's the sadness in a way. If you're head's not screwed on right, you could look at the clouds and start crying. To know that that's not repeatable. But you don't cry when you get taken on a tour of the FBI fingerprint laboratory: there's a different fingerprint for everyone around. And someone who knows about trees was saying that there are no two leaves the same. And I have a book of old photographs by some guy, who at danger to his health, wrapped up in an overcoat, hat and gloves, was taking pictures of snowflakes. The whole book, maybe a thousand snowflakes, all different.

Then, at that point, the big question rises like some prehistoric beast, does that make you happy or does that scare your pants off? And then we turn to calligraphy, music, singing, nursing, publishing some magazines, robbing banks; whatever the metaphor is that commands our interest, to help us make that answer. For me, the answer is: where do we really live? Is our hammock stretched between two voids, or two things that are solid? And we keep digging in, coming up with something.

JB: [bringing out a piece of music] I was looking at this piece of music after we talked last time --

JW: That's a Scriabin.

JB: Yes. I have a question about how this piece of music matches what you are saying. We have talked about seeing the patterns — we see the motif, here, repeat itself, a little bit higher. We see that he chooses thirds, then octaves, then back to thirds, certain harmonies....Can you translate what you've been saying into a practical direction to understand this?

JW: Sure. When you're looking at something like that, you're not expected to know what it is, because it really wasn't known by the composer, and you're just as good as the composer. So when you don't know something, you can still participate in the knowing, you can still participate in the REVEALING of the knowing by saying what it is NOT. That's just as good. I know what it's not. It's not arrogant. Because I have to assume that if the material comes in on the strong beat, it's not humble pie, it's assertive. The downbeat is the step you take to go forward.

And now just the SHAPE. Don't get bogged down with technical jargon: "this is a third, this is a fourth, this is a perverted twentieth." It's nothing like that. We have something that starts without kicking you in the ankle, it starts gently. Then immediately it loses ground [indicates the direction of the notes on the page]. Then it comes right back to where it was, then tries once more to go higher. Then, to balance that reaching higher, he has a wide interval for balance, to stabilize. He comes downhill. Then, with what gives the piece its character, he finishes on the upswing. We know that's a speech pattern for a question. It's not an assertive statement, it's much more waving, hovering. It just comes in on our breath.

And then [indicates the next phrase] it's the same stuff, except with a little more aspiration, a little bit higher. Then he starts again. The first three or four items make us think that he is going to continue doing the old stuff. But he just goes so far, and then gradually, gradually rattles back down, and that's the end.

So, in order to play this, I have to become this; in order to become this, I have to be sympathetic to it; to be sympathetic to it means I have to be able to see, going through all the file cabinets of my life, the photographs, the love letter, the torn pieces of programs and tickets, the articles of discarded clothing. What are the things that I know that this is? Then I'll just use it.

JB: Are you describing making associations in your mind and your feelings with your experience?

JW: Right. Did you ever approach something, not commit yourself, sort of holding back, and then kind of circle around it, and then apologetically, quizzically say, "do you mind if I continue?" Like you, I could see you, as a very shy little girl. There's the doorway, but you don't walk through it, you're standing in the doorway, maybe kind of watching, hoping for something. Maybe you're pulling on your pigtail, or doing something that changes the subject. There's a certain kind of modesty here [in the music]. Now I just have to look under the word "modesty" and there will be references to this.

It works the other way. The composer doesn't know anything' . He's just sitting there, scratching his head. And what comes out, without being dictated, without being forced, is something that he looks at and says, "Oh! What a beautiful, modest shape."

You can always appreciate the way the thing is structured. Sometimes the structure offers a certain percentage of meaning to the object. But here it's a mood.

JB: Do you think he has in mind, or in his feeling, a mood, before he begins, and then uses some tools for what he knows will transmit that: certain patterns of vibrations, so to speak, or sounds? And then he begins, and there is feedback already.

JW: Feedback comes real fast. I don't know if you remember, but before the modern computer there was a very primitive kind of computer that used cards, punched cards. I think that what happens is that there is a certain hole-you run through all these cards until you find all the cards that have the same hole. There's a certain moment when these two items are lined up, like on an astrology chart.

So what we have then is the composer who doesn't know ANYTHING. He's just sitting there stewing. He's stewing. Then there's the IBM card. He doesn't even know what that is. But he's improvising, he's improvising. Nothing. Improvising more. Improvising... BOING! There's a little match for a second. You don't need a huge explosion to get the thing going. The tiniest little flicker is enough.

When you improvise, when you pretend parts of words in a poem, when you're just dabbing at your canvas, when you're just sort of stirring up an egg, you're waiting for that moment when things are lined up, SOMEWHERE, to give you a handle. It's like using pitons in mountain climbing: you don't want to step on the poor whole mountain, you just want a tiny foothold, a tiny access. And everybody knows about this access from their standpoint.

The end of the Scriabin book of preludes has five preludes that he wrote on the death of a child. We don't know what he was like, but we can say that what he DIDN'T do is sit down and say, "I'm going to write a piece of music about my kid." He probably did not begin writing by looking at the end of his pencil. Chances are he began by temporarily using his equipment as the messenger or the conduit of his desire.

If you sketch all the time-go to museums, sketch hands, faces, hands, contours, necks, ears-and somebody wakes you up in the middle of the night, your hand is sketching.... The hand is going to give you that foothold.

JB: Is this what you are saying: Perfecting the craft, and, maybe, perfecting the vessel allows something to come in, something to come through? Is it, as some people would say, a higher energy?

JW: It doesn't matter. Something comes through.

JB: "The message?"

JW: Right. Because the equipment has been trained to be the conduit. If it REALLY is trained, your improvisation or your composition may not be earth-shattering, but it will be legitimate, and it will be a pretty good Xerox, or upside-down picture of what you're experiencing. You have to have built the experience in, and the experience gets built-in through, without sounding cruel about it, the DISCIPLINE of respect.

JB: Respect?

JW: Respect. Respect for the book, the pencil, the piece of paper, the note. Respect for the object that's outside of you. Because if you rely on respect of your own self, you're lost. Very few of us start out with any respect. But you're absolutely right: the craft IS the conduit, the craft IS the vessel.

JB: You say the craft is the vessel. Let's take that to where the music has been composed, you're performing it -let's say you're WORKING at it-maybe it's your own music or somebody else's and maybe other people are listening. Now, each time, it's NEW, then. In other words, once again there is an experience of needing to be connected to something for something to flow through.

JW: You're absolutely right. Absolutely right.

JB: What is that connection?

JW: The connection is respect. Respect for what the real answer is to the question, "Why put yourself out?" Why sit up on the stage playing this dumb music, and dumb people are staring at you, sitting there in their dumb ties and their dumb furs, and they put their dumb hands together and make some kind of barbaric sound? Why put yourself through that? What's in it for you?

The wrong answer is: I know how to do it, so I'll do it. Well, then, you might as well ask the question to a Xerox machine. What's is like for a Xerox machine to do three hundred copies that are exactly alike? What if you're not feeling good? What if your eyes hurt? What if your fingers hurt? What if the piano is too hard? What if the light is too soft? What if people are coughing, burping, doing all sorts of terrible things in the front row?

If there's respect for everybody involved, then your performance will be unique every time. And that's the payoff. A couple of lousy bucks-that's not the payoff. Or someone says, "Oh, you're such a wonderful person. You must be happy to be so talented." That's not the payoff.

JB: Can there be some significance in this performance or event for feeding oneself, besides the fact that you've had a unique experience? There's the implication that you've been nourished, or paid back.

JW: Okay, look. Everybody needs a payoff. I like so-and-so because he gives me money. I like so-and-so because she feeds me. There might be a more elegant word, but "payoff" is good. So, what happens is that the payoff of a spontaneous, constantly adjusted, piano performance is that it's really living. That's like doing an aerial act, a trapeze act with blindfolds on. Because what you're saying is that ANYTHING that comes in will be usable. Everything is up. Everything is alive. Which means, now, if by accident, when you're about to play, some tse- tse fly that's off course by four thousand miles bangs into your hand, and your first chord, instead of a quiet B flat - D flat, is FORTE -- what an opportunity!

So if you're really alive, you'll say "Hey, thank you. We use everything here. We don't let anything go to waste." And when you start the second phrase, you'll accidentally, on purpose, accent that, to make the thing balance. If you are creating something on the spot, you are being hosted by life. Because life and movement mean pretty much the same thing.

JB: You've said that music and breath are one.

JW: If they're not one, they're certainly on intimate terms because one carries the other.

JB: What about an awareness, when playing, of one's body-the sensation of your feet on the floor, the fingers on the keys? But there needs to be awareness of the forms of the music, the sounds. Is it a movement back and forth?

JW: Back and forth. The trick is to know this stuff, then to forget it. Stay out of the showroom as long as you can. Go back into the garage. Go back into the warehouse. Go back onto the assembly line. Learn all the little things. The little things are beautiful, too. Don't court the END of the problem. Stay with it like a glutton. That's my best advice. There's something totally finished and correct if, half-way through this process, the lights go out. Then, in a way, it will be continued at some other level.

SUBSCRIBE NOW

TO OUR MONTHLY NEWSLETTER

Share Your Comments and Reflections on this Conversation:

On Oct 21, 2018 Greg Martino wrote:

I had the pleasure of studying with Julian in the early 80’s.....I had no idea who he was outside of being my teacher, being my teacher was enough, it was what I needed at the moment.I still use processes he taught me almost everyday, I share moments with others that I shared with him. He operated on a different level than most people and was extremely honest at all moments.

I heard him play in San Francisco, he closed some kind of conference on psychology by playing a 45 minute piece of classical music. It was one one the most incredible moments of my life and definitely the most powerful musical one as a listener.

On Feb 22, 2010 Hans Wallin wrote:

I would like to be informed aboutpublications,scores,of Julian White's music