Interviewsand Articles

Brent Nettle & Eldergivers

by Richard Whittaker, May 2, 2005

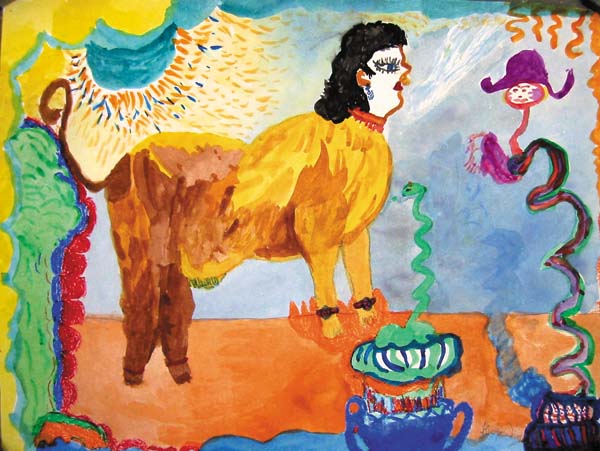

Eldergivers is a non-profit organization with the mission of fostering positive connections between elders and the wider community. They offer several programs toward this aim, one of which is a program of art instruction called Art With Elders. This is offered in Bay Area nursing homes and long term care facilities and includes public exhibitions of the resulting artwork. A second Eldergivers program is their Elder Arts Celebrations which promotes exhibitions of the art work of students, faculty and alumni over the age of sixty-five from local colleges and universities.

MEETING THE DIRECTOR

It looked like I’d arrived first, so I picked a table where I could watch the door. A few minutes later a trim man with a closely cropped gray beard stepped into the restaurant and, looking around, quickly spotted me. As he approached, Alan Watts suddenly came to mind.

It was my first meeting with Brent Nettle, the executive director of Eldergivers. Before our face to face meeting, I’d gotten invitations to a number of Art With Elders exhibits and had become curious to learn more. I’d missed the big Elder Arts Celebrations exhibit at the Di Rosa Preserve in Napa and hadn’t even been aware of earlier exhibits which had taken place at the De Young Museum and the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts in San Francisco.

The greater Bay Area is one of the richest centers of the country in terms of art activities of all kinds, so it’s never a surprise to learn that I’ve missed something. I hadn’t heard about the Eldergivers’ Bay Area Elder Artist of the Year Award, either. Ruth Asawa was the first honoree. Some of the others have been Ruth Bernhard, Peter Voulkos, Paul Wonner, Raymond Saunders and Nathan Oliveira. This year it’s Wayne Thiebaud.

Upon such discoveries, sometimes I wonder what else I’m missing. There are all the important things that could have been missed, but just by chance, were not. And certainly, there are all the things which are always being missed in perfect ignorance. But there is another realm at the edges of these worlds, the liminal areas where the standing of things is too faint to trigger notice. Yet, should the attention be called, something is seen to be there.

Coming to this thought, I see how appropriate it is both to the interiority of artmaking and to our attitudes about elderhood. No justification is required, I think, to invoke the idea of liminality with the territory inhabited by our elders, but I’m moved to quote Mr. Nettle on this anyway: “Did you know,” he asked, “that sixty per cent of elders living in nursing homes never receive a single visitor?” All I have to do is check my own thoughts on this subject to verify their shadowy nature.

The man who walked through the restaurant door, however, and who was now sitting across from me, was quite real. Although cordial in manner, his eyes were clearly at work on the task of appraisal. It was not unpleasant to have Mr. Nettle looking me over as we settled down to the business of getting to know each other. My own tendency, generally reinforced by experience, is to expect something positive from such new territory as our lunch meeting promised; but it would be dishonest not to admit to misgivings. It had been made clear that Eldergivers was about that population housed at the last stop on the line, people without a future, those turning the last pages in the book. I hoped I would find something to offset these dreary thoughts.

Conversation came easily. I learned that Nettle had arrived in San Francisco some twenty years ago from Los Angeles where he’d been the director of business development for an architectural firm. With his background in business administration, he’d done a lot of things, starting out in Detroit in retail management. He’d been an account executive in public relations and advertising, a buyer for a large Midwest retail chain selling women’s fashion wear, and had headed up a worldwide campus ministry for his faith denomination. Not long after arriving in San Francisco, he landed a position in an investment banking firm. It all seemed perfectly in keeping with the carefully dressed, friendly and self-possessed man sitting in front of me, but how had the connection with nursing homes entered into it? Business administration was like that, he told me. It could lead almost anywhere.

When Nettle first arrived in San Francisco, he’d helped found an organization called the Larkin Street Youth Center. As he put it, “These were at-risk kids, runaways from home. Most of them were gay and no one wanted to have anything to do with them.” He told me he had a feeling for the marginalized in our society. “I think it has a lot to do with my spiritual background,” he added, Christian Science. In his high school of some four hundred students, he was the only Christian Scientist. He knew what it meant to be the outsider. He didn’t go into it further, but no more needed to be said.

What about your family? I wondered. His parents were dead, but there’s a brother. Nettle has no idea where he might be. No other family? Nettle shook his head. Suddenly I had the impulse to make some empathic comment, but couldn’t find the words. “I adopt families,” he told me, smiling, perhaps sensing my struggle. “You have friends?” I asked. Yes, plenty of them.

So how did you become involved in Eldergivers? And how did it begin? Just that morning, he told me, he’d talked with the man responsible, his former boss, Doug Kramlich from the investment banking firm. “Did you know,” he’d asked Kramlich, “it’s been seventeen years now?”

THE BEGINNING

It had been the Episcopalians who had started it, Father Fowler, in 1985. He’d started a little ministry to local nursing homes and Kramlich, a member of Fowler’s parish in a Cow Hollow neighborhood—St. Mary the Virgin—had taken interest and become a member of the board. A couple of other Episcopalian churches joined the project, but two and a half years later, they’d run out of money. Then, at the last minute, the Board had secured a small grant from the Junior League.

One morning at work, Kramlich handed Nettle some papers. “See what you can do with this so I can present it to the Board.” It was a job description for executive director of the nursing home ministry. “He knew I was good with words,” Nettle told me. The text went back and forth four times before passing muster. A couple of weeks had gone by when one day Kramlich came into Brent’s office, “I don’t know why I didn’t think of this before, but you’d be perfect for this position.”

“Why would I want to do that?” Nettle replied. He couldn’t think of anything he’d rather not do. “Our society has a real fear and hatred of nursing homes. It’s visceral. Nobody wants to go there.” But Kramlich wasn’t put off. “Just take it on half-time, do some fund-raising, get the program up and running, and then come back here full-time.” It would just take two years Kramlich figured. He asked Nettle to take two weeks before giving a final answer. “Pray about it,” he added.

“That was a low blow,” Nettle said, laughing. “But I agreed, and as usually happens when I pray, something bigger than my immediate wishes and attitudes began to come in.” Nettle had fallen in love with San Francisco and realized he wanted to give something back to the city. There was an issue of social justice, too. Besides, he thought, there were fifteen or twenty other applicants, most pastors, ministers and priests. What were the chances they’d select him, a businessman? Nettle agreed to apply for the job.

It turned out there were other business people besides Kramlich on the board. They wanted someone who could make it work, and they offered him the job. Nettle described his acceptance as coming in kicking and screaming. That was seventeen years ago. What had brought about the change of attitude? Could he give me an example?

Celestine came to mind. Of the several cranky and difficult residents living in the five nursing homes in that first ministry, she was the worst. Finding volunteers to make regular visits to the nursing homes was one of Nettle’s challenges, and it would be hypocritical to ask others to do something he would be unwilling to do. So Nettle decided to visit Celestine weekly and to stay at least a half-hour each time. It was an exercise of extreme patience, he told me, but he persisted for several long months. Eventually, Celestine’s behavior began to change as she began to trust he’d continue making his visits. A wonderfully dark and caustic sense of humor began to emerge, and “I liked that. She let me see things no one else saw.” Nettle began enjoying his visits, now often punctuated with periods of racuous laugher. The noise began causing staff to look in just to see what was going on. It also came to light that Celestine, like Nettle, had grown up in Detroit. There was common ground in that, even though fifty years separated them. The coincidence seemed another confirmation of the path Nettle now found himself on.

A few days after telling me about her, Nettle realized her name had been Catherine, not Celestine. Sixteen years had passed, after all, but the trick of memory was revealing, I thought. Celestine.

In any case, when Nettle’s two year commitment was up, he told Kramlich, “I think I’ll take the project on full-time.” Kramlich smiled, “I thought that might happen.”

ENTER ART

One day, on a visit to Victorian Healthcare Center in the city, Nettle noticed a number of drawings and paintings in a hallway. They weren’t very good, but he asked the administrator, Linda Williams, about them. An art therapy program had been set up at all five of the Hillhaven facilities, she told him.

Nettle got to thinking. There was something wrong about it. Art therapy was based on a premise of illness. It was true that the elders in these places were isolated, suffering, but should their age be regarded as the equivalent of having “fallen ill”? Nettle began pestering the art therapist. “Can’t you expect more out of them?” he asked her. It wasn’t only that Nettle had philosophical differences with the art therapy approach, but another idea had come to him as well. Could the art work of this isolated population become an avenue for reconnection to the larger society? It wasn’t long before Nettle’s interventions were on the verge of precipitating a crisis. “I thought we might lose all five of the places,” he told me.

He went back to Williams and talked with her about his views. She listened. “Has there ever been an exhibit of this work?” he wondered. Williams agreed to fund one if Nettle could find a venue.

When I’d asked Nettle about his own relationship with art, he’d recalled experiences with his father, an avid amateur photographer. When Nettle was eight or nine, his scout troop sponsored a photo contest. His dad was determined that his son would win first prize. It was winter. “We drove out into the country. There was snow on the ground. We walked off into the fields through the snow looking for just the right spot.” That closeness to his father was memorable. The winter cold didn’t bother him, he remembered. The photos were in black and white. “I liked the quality of the images. The clarity. Maybe that was the beginning of my love of nature.”

Later Nettle took a few courses in college. Art History, a couple of studio classes. He remembered looking at Gauguin’s Tahiti paintings. The colors weren’t right, he thought. He talked it over with an Australian friend. “He taught me to see all the different shades of green in the grasses and bushes.” Listening to Nettle’s recounting, it was easy to feel his natural responsiveness to beauty, but he hadn’t pursued art. His interests had taken him in other directions. Perhaps that’s part of the reason he was able make his next move in relation to the situation at the five Hillhaven facilities.

THE FIRST EXHIBIT

“I approached Grace Cathedral,” he told me. The Episcopalians had started the ministry and I thought, why not? They agreed. Sixteen elders in wheelchairs were present at the service at the cathedral and were celebrated in a reception afterwards. Close to a thousand people were there. During the service, the priest recognized them and there had been a huge round of applause. “Try to imagine the impact of that.” It certainly had an impact on Nettle. It led to the “First Annual Art With Elders Exhibit.” The road ahead opened.

Nettle went back to Williams and suggested they begin a real program of art instruction. “Do you have an instructor in mind?” she asked. One doesn’t spend years in business, I suppose, and let a minor problem stand in the way. “Sure,” he replied.

He scrambled and, as luck would have it, help was close at hand. His friend Debra Dolch, a respected conservator, knew someone who would be perfect, Mary Arkos-Pagonas. Mary, an artist herself, accepted the job and began teaching painting classes at the five Hillhaven facilities. Finding Arkos-Pagonas allowed Nettle’s vision to unfold. What had begun as an unfocused small ministry to elders living in nursing homes now had a way of crossing the divide between the isolated elderly and the community at large. With the help of Arkos-Pagonas, the number of facilities connected with Eldergivers began to expand and the “Art With Elders” [AWE] program was underway.

It was not a scenario that Nettle could have imagined in the late 1980s, I’m sure, as he settled in to his new job working for Kramlich in the investment banking firm. To the extent that Nettle had been involved in social service programs, he was used to working with youth. Youth is attractive. Its virtues hardly need enumeration, but what had Nettle found in his years of working with the elderly?

“Youth lacks experience while elders have that in spades,” he said. Not all the elderly have gleaned something essential from their experience, but many have; they’ve gained a broader perspective. As Helen Luke says, those elders who have grown into the gifts of old age have acquired a taste for the joys of things in themselves. The machinations of the ego have subsided allowing something impersonal and finer to enter. What old age can bring, we call wisdom. Nettle feels strongly about this, and about the cultural loss we suffer for the isolation of our elders. “When we marginalize elders, we marginalize experience, we marginalize what is spiritual, we marginalize what is intangible, we marginalize the imaginative, we do all sorts of things to keep what is best about us hidden.”

POWERFUL FRIENDS

Besides all the other things art can be, it has become, for Nettle, the wedge for breaking through the barrier that separates the elderly from the rest of us. It’s showing itself to be a powerful tool, and over the years, Nettle has managed to find a few powerful supporters of this endeavor. At an Art With Elders exhibit in another church a friend of Nettle’s nudged him and pointed at a man across the room. “That’s Harry Parker over there”—director of the San Francisco Fine Arts Museums.

Nettle found Parker sympathetic and interested in hearing about his program. Would he back an Art With Elders exhibit at the De Young? The staff wouldn’t go for it, Parker told him. Nettle persisted, “But you’re the boss, right?” Finally Parker allowed, “I suppose I could get away with it once.”

At that point a few years of instruction and expansion had gone on. The art was better and there was more of it. The sixth annual Art With Elders exhibit took place at San Francisco’s M.H. de Young Memorial Museum in Golden Gate Park in 1997. On this first occasion, because of the general misgivings of the staff, only a few hours were made available for the event. Something like fifty pieces of art were brought in at 4:30 PM. Nettle had found a couple of strong young Mormons to help, farm kids doing their two-year ministry in San Francisco. By 6 PM everything was up and ready for the artists and their guests. About one hundred fifty attended. Everything had to be down and out of the building by 9:15 PM. It was perhaps the most abbreviated exhibit in the De Young’s history, but the artists were exhilarated, and the museum staff found it far more appealing than they had imagined. The event, only a few hours long, marked a turning point for the program.

LAGUNA HONDA

Not long after that Nettle got a phone call from a young man fresh from completing his MFA degree, Mark Campbell. He’d seen the Seventh Annual Art With Elders exhibit at Flax Art & Design, and had liked what he’d seen. Were there any jobs available? Less than a week before, Laguna Honda Hospital, the largest nursing home in the country, with 1200 beds, had contacted Nettle. Could an Art With Elders program begin there? It would take a very special individual to manage that. Mary Arkos-Pagonis seemed to have been heaven sent, and now a second individual of similar caliber was needed. That was the moment that Campbell appeared. “Mark’s concept of elders and his life-philosophy were elegantly compatible with Eldergivers,” Nettle said. “plus, he’s an inspired teacher and knows how to deal with bureaucrats.” But the Eldergivers program at Laguna Honda almost never happened. Bureaucratic problems rose up, nearly stopping it before it began.

Nettle went to the hospital administrator, Larry Funk, who, as luck would have it, turned out to be “someone capable of eliminating every negative element from the definition of bureaucrat!” He cleared the way. Now Campbell teaches one hundred students there with classes three times a week. It also turned out that Arkos-Pagonis and Campbell worked very well together, and with their dedication the program began to flourish.

GROWTH

Exhibits at the De Young continued. In 2000, there were six hundred and fifty guests at the reception and the work of ninety artists spilled out of Hearst Court into Gallery 27. The exhibit was up for two weeks. Somewhere along the line, the idea occurred to make it a traveling exhibit. Now the annual Art With Elders exhibit is up year round in public buildings such as City Hall, Levi Strauss, [in the early years] One Market, 150 California, War Memorial Performing Arts Center, Genentech, and so on. An estimated 100,000 people a year now see this work.

When the De Young was closing for remodeling, the search began for another distinguished venue. Nettle called Tom Meyer, of Thomas Meyer Fine Arts, a member of his advisory board. Why not approach the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, Meyer suggested. A meeting was arranged with Renny Pritikin, executive director, and Rene de Guzman, curator. It was an awkward meeting. What interested them was avante garde work, they explained. You mean young artists, Meyer responded. Wasn’t Yerba Buena supposed to be open to the whole community? Meyer asked. As Nettle described it, Guzman “quickly caught on.” Maybe we should give this a try, he decided. A date was set for 2002.

The night of the exhibit there were four separate installations, three in keeping with current curatorial standards, and then the Art With Elders exhibit. As Nettle described it, there was a huge crowd on opening night, fifteen hundred—mostly young people. At first, they crowded into the first three installations and after a half hour, they began drifting over to the Art With Elders work. Each piece had a little bio and a photo of the artist, and people started reading them. “Hey, come over here!” began to be overheard. “Some read all ninety of them,” Nettle said. People lingered there. The young Yerba Buena staff, “pierced and tattooed,” enjoyed the exhibit also. “It’s a great show,” they told Nettle. “It’s accessible!”

BEYOND MATERIALITY

Eight or nine years had passed, plenty of time for Nettle to think about the condition of old age and to become more sensitive to our attitudes toward the elderly. Like nearly everyone else, Nettle himself had resisted the prospect of spending his time and energy with elders, especially with the population most sequestered and seemingly least capable of offering anything to a younger man with things left to accomplish in life. But his experience has confirmed the values he’d learned as a child growing up. There are things more important and rewarding than “materiality, the superficial, the immediate and the evident.” Wisdom, he said, is gained from grappling with others on many levels. It is grounded in lived experience. It’s hard won, and it takes time. Not everyone finds it, but some do. Why were elders left out of “the circles of conversation”?

Nettle began to notice that not only the sequestered elders were left out, but nearly all the people over sixty- five he talked with also complained of the same thing: disregard. An entire section of the population closes down and whatever they might give is lost.

Pondering this problem, one day Nettle was talking with Harry Parker, by then a long-time friend and supporter of the work of Eldergivers. Nettle is also a big fan of Parker. “He’s a regular Johnny Artseed,” said Nettle. “Some day this city will realize and understand all the art trees Harry Parker has planted.” Parker was telling Nettle about the Youth Art Festival at the De Young Museum which he’d founded. “Would you consider launching an ‘Elder Arts Festival’?” Nettle asked spontaneously. Parker asked what he had in mind.

There was nothing specific yet, but Nettle suspected that the older students, faculty and alumni of art schools might be feeling the same disregard affecting other elders. A little research proved it was true. Parker is on the Board of Trustees of the San Francisco Art Institute and introduced Nettle to someone on the staff there. Would they be willing to host an exhibit in their Diego Rivera Gallery? They were willing and gave Nettle a copy of their list of alumnae. Visits to San Francisco State, City College and CCAC yielded similar results and a new program was born, “Elder Arts Celebrations.”

In the year 2000, the first Elder Arts Celebrations campus exhibits took place. It has become an important part of the Eldergivers work, with Mark Campbell directing the program. Three years before the EAC program was conceived, Harry Parker had strongly encouraged another concept which had come up, the “Bay Area Elder Artist of the Year” award. It had been Parker’s support that had made this program possible.

GROWTH OF A GOOD THING

Robin Myers joining Eldergivers was another key event. “Robin has been fantastic,” Brent told me. “It’s largely due to her that we now have thirty long-term care facilities and eleven artist instructors. Our reach now extends beyond San Francisco to Alameda, San Mateo and Santa Clara counties.” Myers has been effective in securing grants as well, including two NEA grants and multi-year grants from the Community Arts and Education Program of the San Francisco Arts Commission. Corporate support has also materialized. Cisco Systems has been a generous supporter and, as Nettle puts it, “every now and then an angel comes along” like Debra Dolch and Mary Wilbur Thacher, for instance, who have been very generous supporters. But besides financial support, there is the intangible support of positive response. Those who visit the Eldergivers exhibits are invited to leave a written response. Nettle says, “It amazes me how many people will stop to do this, and we don’t even provide a pencil!” Here are a few typical comments: How wonderful of you to give them this opportunity! Wow, this is very touching! Very moving! I didn’t know they were capable of doing this! Extraordinary! I’ve gotten an entirely different sense of elders! People buy the art, too, he added.

But as with every other art organization I’ve had any contact with, money is always in short supply. It seems an endemic condition for artists and art organizations. Eldergivers is a 501(c)3 non-profit, so donations are tax deductible.

In following issues, we will meet some of the individual artists and instructors and hear more of their specific stories. In my conversations with Brent, I heard a couple of such stories. He pointed out that one of the things most surprising to others is what some of the chronically ill elders are capable of doing against great physical odds in these art classes. One Japanese lady, 93, was so crippled with arthritis that she could barely move her arms to paint across an eight and a half by eleven inch format. A special mural project was undertaken in her nursing home. A professional artist came in and worked with the residents to decide upon the design for their activity room wall. When the painting got underway, some of the residents became involved in the actual painting. A lot of people noticed how this woman’s painting strokes somehow had expanded almost miraculously. I mean, way, way beyond! [Nettle spread his arms wide.] “She forgot her arthritis. Totally forgot about it.”

There was another woman at another facility who had been dead-set against entering the art class. “I’m not an artist!” she said. About six months later she was totally immersed in it. She had such a bad case of emphysema that she could hardly breathe, but during class, Nettle told me, she didn’t need her oxygen tank. ∆

ELDERGIVERS has other programs that fulfill its mission to foster positive connections between elders and the wider community. They can be contacted at:

Eldergivers

1755 Clay St.

San Francisco CA 94109

phone 415-441-2649

web site www.eldergivers.org

About the Author

Richard Whittaker is the founding editor of works & conversations and West Coast editor of Parabola magazine

SUBSCRIBE NOW

TO OUR MONTHLY NEWSLETTER

Share Your Comments and Reflections on this Conversation:

On Sep 29, 2007 Bruce Lauritzen wrote:

Very interesting success story about Mr. Nettle and your shows. I was in your Yerba Buena show with a large canvas "Mirage," which ended up in Germany, Born in SF and MFA at SF Art Institute. My first solos shows were in Milan and Rome in '64, and have had 150 shows since. Current show with I.Wolk allery/Cliff Lede Gallery in the Napa Valley. Work is in worldwide collections, inc. SFMOMA & SF Legion of Honor. I was proud to be a part of your exhibition program and hope for another shot at it. Good luck and keep up the good work! BL