Interviewsand Articles

A Conversation with Peter Veilleux: East Bay Wilds

by R. Whittaker/Peter Veilleux, Sep 8, 2021

It was after business hours late in the afternoon. I’d driven to East Oakland to talk with Peter Veilluex at East Bay Wilds, his nursery featuring only native California plants. Pavi Mehta told me about Veilleux: “He’s one of those people who have followed their passion. I’d love to hear where a conversation between you two might go,” she’d said.

Before arriving, I’d listened to an earlier interview Peter had done so I had some background about his story. When I got there, he still had a few things to finish up, so I wandered around happily taking photos. There’s much to see. Besides a wide array of native plants, there’s a variety of objets d’art he’s collected over the years. They’re set out among the plants, decorate the fences and enliven the walls of his open-air office.

Veilleux has a serious appetite for ceramics, and a sense of whimsy and, while the main focus of his passion is for finding and spreading knowledge and appreciation of native plants, he keeps his eyes open for objects redolent of other times, other places and other states of mind.

It wasn’t long before he motioned me to join him and his dog Lucy. A package had been delivered and, as we sat there, he was opening it. “My friend in Italy sends me things,” he said.

That’s when I began recording. – Richard Whittaker

Peter Veilleux: I can’t wait to see what Freek sent me! [pulls out a colorful plate] Can you believe? I’ve been into pottery since I was a kid. And Freek has taught me a lot. I mean, look at that! This is late 1700s. It’s Chinese and made for the Thai market—actually, for the imperial family and their friends. They loved these colors. Isn’t that beautiful? See how these glazes are really thickly applied? That and the colors is how you can identify pottery made under the Qianlung emperor. He was really into arts of all kinds and he set standards very high for craftsmanship.

works: It’s an elegant piece. And this is your friend in Italy - Freak?

Peter: My friend Freek Pals. Yes, it sounds like “freak” [laughs]. He lives in Amsterdam.

works: Good name! How did you get into a love of pottery and ceramics?

Peter: Making ceramics when I was a kid is when it started. All my life, when i got interested in something, I became obsessed. I stopped making ceramics around 12 or 13, but I’ve collected pottery for a long time now. I visited potters and hung out with potters in New England. There are a lot of them in Vermont and New Hampshire.

works: So tell me a story about your pottery. I’ve got to hear one before we move on [laughs].

Peter: [laughs] Well, I was really into my own thing. I would get books out of the library on pottery. I mean, this was back in the early 70s. There was a lot of experimentation. I was making these big, clunky pieces that were bizarre.

works: Where did you get the clay?

Peter: There was a potter down the street from me who actually taught me the basics. She had other students, too, all much older than me, but i learned from all of them.

works: Did you do hand-building?

Peter: Mostly hand-built, but some on the wheel.

works: And you loved it.

Peter: I loved it, loved it, loved it! Although my father wasn’t always excited about it.

works: Tell me a little about your father.

Peter: He was definitely of the “buck up buttercup’” [toughen up] epoch. We had a difficult relationship for a few years, but I’m not kidding you, everybody loved him. He’s really a kind, kind, good person and helped so many people in his life. He had this way with people, which is remarkable. People of all ages trusted him. I remember once when I was little, he left around 1am and came back around 4 or 5am. He drove to Boston to pick up a friend of my family - this woman who had been lonely her whole life. She had recently fallen in love for the first time and, apparently, he died of a heart attack while they were together. She called my folks, and even though he was exhausted, he didn’t hesitate to jump in the car and drive for several hours to bring her back to our home. That was typical. When I look back on it, he was very progressive—especially for a Republican! Thankfully he’s fully reformed now and even volunteered for both of Obama’s campaigns.

But between my sister and my dad, my family has a lot of land back there, really beautiful land, something like thousands of acres now. We started off with twelve acres when we built the house in 1974. It was my family’s way to prevent the rampant, destructive development all around us. It’s along the Connecticut River and up the mountain a bit. It’s at the sharpest bend of the river that’s sort of a capture zone for rare plant species.

When I was a little kid, my dad would take us—and sometimes our entire class—camping and hiking and canoeing all over the Northeast. We’d have sixty kids and my dad was the chaperone. Lots of my friends called him “Father Nature.” He was always helping us with science projects, too. His enthusiasm for identifying plants, birds, animals was contagious. as is my own enthusiasm for native plants. All of us won first place in the local science fairs year after year.

works: And your mother was supportive of these things?

Peter: Oh, very.

works: Both your parents sound very loving.

Peter: Very, very. Their kindness and love of nature had a big effect on many of my friends. They’ve maintained communication with many of my them from different times in my life - most of whom I haven’t been in touch with for years.

works: I was struck by what you said earlier about how your dad has an organizing bent and likes to categorize things and bring order.

Peter: Yes. Human order. The categorization of things is the first step in awareness—acknowledging things by naming them. It’s comforting even though it’s just the first step.

works: And your mother…

Peter: A different kind of order. It’s more like music. Music has an order—like harmony; it’s in conjunction with other orders, a way where things are moving synchronistically or something. My mom has been quietly spiritual for a very long time. Others probably call it religious, but she isn’t dogmatic, and she has a higher understanding of religion than almost anyone I know. She struggles to live a very moral life, but never imposes her morals on others. She doesn’t talk about these things, but lives them. I remember once when we were camping, she said that the greatest thing we can do for others is to hold up a mirror, and help them understand that it’s all about love and kindness.

works: An intelligence of the heart there? It can read things and doesn’t have to calculate the same way.

Peter: Right. Or put things in boxes.

works: And your father has a heart, too, obviously.

Peter: Yes. Well, they were both valedictorians in the small Catholic school we all attended. Very smart. But good people, you know? My dad has Alzheimers now. It’s advanced so rapidly, but thankfully he’s kept his sense of humor.

works: That’s a blessing. You know, I’m tempted to make a leap here. You were in Honduras working with indigenous people in a village of 300 and said, in that little village there was amazing diversity. Everyone had their own qualities.

Peter: Very unique. It was almost like you had the same diversity among those 300 people as you have in a big city. There was a real respect for each person’s individuality there.

works: It reminds me of what A.K. Coomaraswamy wrote about traditional cultures, how each person always found a vocation, a role that really fit them.

Peter: Right. There are all these ways that people are allowed to blossom in a village like that. I saw it with the kids - all the kids. The whole time I was there I never saw any kid struck, or anything like that, by an adult. They were very respectful of the kids and when something was wrong, everything stopped. When a kid falls while playing soccer, everyone would stop and comfort that kid. You didn’t see that in the Latino community. But among the indigenous people—I lived with the Tawahka [Sumo] people—it was like that. There was an enormous amount of kindness.

works: That supports what Coomaraswamy wrote.

Peter: Yes. I remember when a Latino family moved in. He worked for the government—forestry or something. He was really a nice man. They all were. But every now and then, mom would lose it with the kids [laughs] and yell and smack them. I saw the whole village look on in horror. They were really nice folks, but the way they raise their kids is so different.

works: And you’ve seen a lot of other indigenous cultures. Can you make any general statements about these indigenous cultures?

Peter: It’s so hard to generalize because from one village to the next, even with the same culture, there was so much variation. Traveling in Mexico, you really see this. In one village I would be so comfortable and feel at home, and in the next village, I couldn’t wait to get out of there. I don’t know what that was about. Definitely, there are huge differences and there’s tremendous poverty and violence throughout Mexico and Central and South America. The Tawahka [Sumo] are known for being very timid and wary of people from the outside. It took me three or four months to settle in comfortably there. In the world, it seems there are people who are attracted to people from the outside—the other—and there are others who are attracted more to the similar. They both can be wonderful people. The Tawahka are surrounded by the Moskito people. You’ve seen Moskito people?

works: No.

Peter: They’re from La Moskitia in Honduras and Nicaragua. They usually have very dark skin, sometimes blond hair, blue eyes—and black skin. They’re attracted to the other, hence this wonderful racial mix. And their language is an amalgam of different languages. They even have a lot of vocabulary that comes from English-speaking pirates. For bucket, they say “bookit.” A mirror is a “looking glass.” If you ask, “How are you?” (Nakisma?) they answer with: “Faien, man!” [laughs]

works: [laughing] And I’d been wondering, “What am I going to talk with Peter about?”

Peter: I’m jumping around a lot [laughs].

works: No. You’ve had such an interesting life.

Peter: The villages where I lived were very remote. Most of the people in the village had never seen an automobile at the time. Back then there were no roads to get to where we lived. It was very remote.

works: You’ve spent a lot of time living with indigenous people.

Peter: On and off for eleven years.

works: Can you share a couple of things from those years that means the most to you?

Peter: One of the jobs I was hired to do by indigenous groups in Ecuador was to coordinate international publicity for this march of ten thousand indigenous peoples from the Amazon up to Quito to demand underground rights to their land so they could control it. Conoco and other companies had done terrible things. Ecuador had the largest and most organized groups of Indian people on the whole continent—by a long shot. Every community had an organization with elected leaders and I worked at the national level with a man named Luis Macas. He died quite a while ago. He came here once and stayed at my place in Oakland—the gentlest, sweetest man you could imagine. He was Quechua, and the first president of the Confederation of Indigenous Peoples of Ecuador [CONAIE]. Today, if you go into houses in practically any Ecuadoran village, even the most remote ones, you’ll see a photo of him there, and sometimes a little altar. He was a very quiet person, but when he spoke, everyone listened.

.jpg)

works: Was he a shaman, too?

Peter: No. I knew many of them, but he was not. He was a politician, not like you’d think of, but he was able to bring culturally disparate people together from all over the country; they would agree on a constitution, laws, infrastructure investment—in essence, a government.

works: It sounds like he had some inner authority, something people could feel. Am I making that up?

Peter: No. He did! Millions of people listened to him and were ready to go to bat for him. And he was the most soft-spoken person you could imagine. But he very carefully chose his words. There is a lot of mistrust between different Indigenous peoples throughout the Americas. Intentions are always called into question, but he transcended that. It was obvious to me that his intentions were in the right place.

works: There must have been something present in him that operated on a different level.

Peter: Yes. Definitely.

works: I want to make a leap here, and tell me what you think. In your relationship with, and your love of, plants and also with photography—do those things have roots in a different level of some kind?

Peter: Well, it’s been since I was so young. Some of my earliest memories are of finding plants and becoming obsessed with them. I was five or six and walking along the shores of Mountain View Lake in NH. I found some wild mint—water mint growing in an abandoned boat—and I picked it. I can still remember the effect its fragrance had on me. I wanted to know all about it and made tea with it and transplanted some to our house. That’s when I first became obsessed with plants. I’d go to the library and check out floras and books on herbs and read them cover-to-cover, often more than once.

works: It’s impressive that you would devote yourself with that intensity at that age.

Peter: But it drove everybody crazy. I remember my mom saying, “Can you talk about anything but plants, please?” [laughs] Well, the obsession continues to this day. It waxes and wanes, but is always there.

works: Fascinating. There’s something so deep about that.

Peter: And I don’t know what it is. But studying and reading the floras and plant guides from different places—when I think about it rationally, it doesn’t make sense. What did I get out of that? But I got something, and it’s deep in me. It’s happened many, many times that when suddenly seeing a plant for the first time ever, its scientific name just comes to me—boom!—like that. Wayne Roderick—who was the Director of Tilden Botanical Garden many years ago—as well as a mentor for me, called this “habit recognition,” which is different from the traditional keying out of plants. Both of these methods are necessary for me though.

works: That’s fascinating and kind of mysterious. It’s a different part of the mind working, isn’t it?

Peter: Yeah. And I think it runs in families, too. My great grandmother was an herbalist. She would make pills and extracts out of plants she found in the mountains around where I grew up. Often older people I met would comment that I reminded them of her. They bought a big old crumbling stone house with a tennis court and the first thing she did was dig up the tennis court and plant her wild ginger and medicine plants from the mountains there. My family is Quebecois, and she founded the American—French Canadian Friendship Society. She was also one of the only French women who could read and write in that region.

works: That’s a great story, digging up the tennis court to plant a garden. It says something, doesn’t it?

Peter: [laughs] Yes.

works: When my family was living in a little town in West Virginia, my mother dug up some wild sassafras roots behind our house and made tea. She didn’t’ do things like that much, but the smell of the sassafras—it’s an indelible memory from over sixty years ago.

Peter: Yes. [laughing] And I spent time in West Virginia, too, and I love the smell of sassafras and tupelo. What part of West Virginia?

works: Southern, very lush, deep in the Appalachians. I spent a good deal of time wandering around in the woods and along a little creek. Those of us who have had that childhood experience of nature are kind of blessed, I think.

Peter: My dad is most comfortable in the woods. And he’s really good at introducing people who aren’t used to that to the experience. He loved to fly-fish, too. Every year, he’d organize a pilgrimage of sorts to Tim Pond—a lake in the woods way up in Maine. He always had such an interesting group of friends with him—the conductor of an orchestra, a circus veterinarian, farmers, and often a priest. I’d go out in the canoe with different friends of his each day and inevitably they would talk about how much my dad meant to them. So that’s the kind of effect he had on so many people—really interesting people, too. My dad was very good at tracking animals, fishing, hunting, cooking on a campfire, etc.. My family lives in the most conservative area you can imagine, and they are so not conservative, despite being surrounded by Trumplandia.

works: Now you said something about the geology of California - that the ice age wiped out most of the plants in North America except in California.

Peter: Yeah. There were pockets throughout the continent, but generally, California is the one large area that stayed ice-free during the last few ice ages.

works: And you were telling Pavi you had some trouble adjusting to California.

Peter: Whenever I spend time somewhere, I go through a period of inquieto until I’ve figured out a lot of the plants there. California took me a few years to adjust to. When I feel like I know what plants I’m seeing and have some understanding of them, then I feel like I’m settling in.

works: Going back to shamans, do you find it credible that if one is sensitive enough a plant can reveal itself or communicate something? Like a shaman would never make the mistake of eating a poisonous plant, or might recognize a plant he needed to eat. Does that make sense to you?

Peter: Yeah. I think magic is not some miraculous thing. It’s more a combination of knowledge and the ability to act. I’m hesitant to talk about magic and witchcraft and any kind of pseudo-science. Shamanism is not an easy topic. There’s lots of amazing things out there, but I’m reluctant to talk hocus-pocus. The natural world is really interesting without adding my own personal fantasies to it! I love science, but I’m also comfortable with the fact that our understanding of the world is minute in comparison to the mysteries all around us.

I think of a story a friend told me when she lived in Africa in the 1960s. She was sitting in a circle with the village mothers and they were making curds by shaking gourds full of goat milk. The women kept laughing at her and telling her that she was not doing it right. It took her quite a while to get it, and when she did, the whole group acknowledged it at once. It’s a rhythm that’s learned, but cannot be put into words. Languages, music and art are kind of like fossil-remains of previous understandings of what’s real and important. But without language, music, rhythm, art and craft there is no understanding.

works: On a late night radio show I heard while driving through Arizona, a Navajo man was talking about hippies in the 1960s. They would show up at the reservations having read Casteñeda’s books. This Navajo man said the magic was really just about being able to see what’s in front of you. The question is, what does it mean to see what is there? It sounds so simple.

Peter: There are so many levels and ways of seeing. Sometimes I “see” with my nose. The connection between memory and scent is really strong with me. I get flooded with memories when I smell plants—a mint plant, or eucalyptus or bay laurel tree. When I smell these scents, it unleashes a cascade of thoughts for me.

works: The bay laurel has such an amazing smell. How about sage?

Peter: Absolutely. All fragrant plants! Some have horrible smells, but they’re all interesting. There’s one genus of plants that men tend to really hate the smell of, but women enjoy, the Stachys genus.

works: I heard a story from a woman; I’ve forgotten her name. Her mother had become schizophrenic when she was growing up and she was always worried it might happen to her. So she took a very conventional path and became a pharmacist. She suffered from migraine headaches and one day she was walking through a botanical garden and a plant said to her, “Eat me.” That scared her; she thought she was going off the rails. But long story short, it turned out that plant did cure her migraines. And now she’s an herbalist after studying with a plant shaman in South America.

Peter: Wow. I did study with some shamans a little. Among the Tawahka there was this curandero. We’d hike in the mountains on trips for two or three days and talk about plants and how they work. We had such a kinship and, when it came to plants, we had a very similar relationship. I learned from him that plants affect us in many different ways. It’s not just about ingesting something that produces a physiological reaction in you. More often than not it has to do with the way the plant is used, and even the incantations used. For instance, there was one fern that was used when somebody was really suffering with guilt. In the communities where I lived, people could die of guilt if they did something against the community, even in some little way - things that people around here do every day [laughs]. But there was a cure. You’d lay down on the floor and a curandero would wave this fern all over your body in a specific manner, slowly, slowly, while reassuring you that all was now forgiven. For the person suffering, it was all tied to that fern. For me, it was what was being said or communicated, you know? [laughs]

A shaman is often a magician of sorts too. They can turn bad intentions into a physical thing—maybe an egg or black snot or something—something which can be evoked and contained in order to elicit a strong catharsis in the individual. This is where healing lies.

works: What was it like for you having this shared feeling about the plants and spending all that time with him?

Peter: When I’m walking in the wild, it’s like every plant—there are so many plants that just pop out at me and I want to know about them. If I don’t know what kind of plant I’m looking at, I’m kind of uncomfortable. And here was somebody who had this knowledge about them. The plants are all different there, but by that time, I’d learned a little about some of them. So just having a little bit of knowledge, and then listening to him, who had a lot of knowledge about them, made me feel a tie with him.

works: So what does this knowledge about a plant really consist of for you?

Peter: I think the first thing is naming. The naming of things is really important. Once you get going, the Latin names are important because you begin to see how they fit in with other plants or at least how we currently think they relate. Genotyping is really challenging a lot of our old assumptions and leading to so many changes to taxonomy. That’s fascinating for me. I wasn’t really comfortable out here exploring in the mountains and other areas until I knew the names of at least some of the plants. It gives me a starting point. When I find a new plant, particularly a new genus, I spend hours and hours poring over floras, mostly online, until I get some resolution.

works: It seems that we’re learning that plants have a whole lot more going on than we understood. What do you think about that?

Peter: Well, we’re learning about plant communication a lot these days. It’s all mysterious and interesting. There’s some fascinating research being done. But plants are also very different from us. Like I have no qualms about cutting down a tree if it doesn’t belong there. I don’t feel like there’s any problem between me and the tree, even if I do that - especially if it doesn’t belong there. I’m talking about invasive species. What I’m really into are native species.

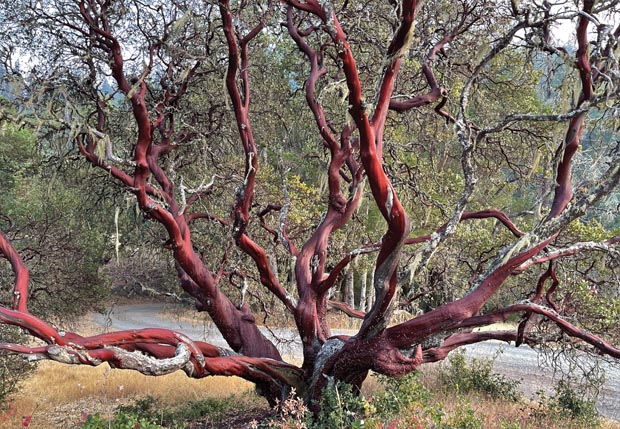

I try to get out every weekend into some place here in California to explore. I’ve been doing it for twenty years. Sometimes I’ll pay somebody to drive my car along and I’ll walk along the road up along the ridge tops like in Lake County or in Big Sur. I can do that forever. Mines Road in Livermore is close to 99% native in many areas, and when I get to any place where I’m surrounded by native plants, I’m so happy. I would do it every single weekend if I could.

works: Who was that famous guy from Harvard? [Richard Schultes] He coujld identify plants in the Amazon from a plane flying over them.

Peter: I don’t know, but I do it from a car at sixty miles an hour. The last of the old time botanists died a couple of years ago, Dr. James Reveal. I never met him, but he wrote to me because he saw some photos of mine. He was writing the buckwheat section on the flora of North America. He said, “This is a special one. Why don’t you give it a name?” It was from a cross that happened here at the nursery. So I named it after a friend of mine, Dave Amey, and Dr. Reveal wrote it up: Eriogonum ammeii - East Bay Wilds Buckwheat. It’s one of the last things he did before he died and the whole description is now entered into the North American flora.

works: That’s an amazing story. What makes you so happy out exploring the flora in different places? Can you say more about that?

Peter: Oh, my God. It just feels like I’m a kid in a candy store. Where it’s all-native there’s a harmony. It’s like seeing music. You know what music does to your heart? It’s the same thing. When I’m exploring and taking pictures, I’ll suddenly find myself dehydrated and hungry, because the whole day has just flown by!

works: There’s a joy there.

Peter: Very strong joy. It’s almost ecstasy.

works: And in the interview with Pavi, you were describing how sometimes the sun is caught in the…

Peter: The sun coming through the grasses! Yes. Exactly like seeing music. That’s the only way i know how to describe it. Like seeing music!

works: That goes right to your heart, doesn’t it?

Peter: Yes. And it’s very important for me to share it with other people.

works: The impulse to share such a joyful experience, what’s it about?

Peter: I don’t know. It’s about art and creativity and craft. That’s where I find synchronicity in the world. I think all artists, in a way, find that synchronicity—and the accompanying dissonance, too. It really is about sharing, and it’s very important for me to share that information and to turn people on to plants, big time.

works: Would you say that something is acting through you?

Peter: It’s acting through me. Exactly.

works: Something nourishing? And that other people need this same nourishment?

Peter: Oh, totally. And it’s nourishing myself. It feels like I’m getting my batteries recharged when I’m out there. And when I’m able to share it through photos or whatever, that just doubles the pleasure.

works: I understand that, but mostly, our culture doesn’t really help take us there.

Peter: Yeah. I live in the Latino community and I’m sort of fluent in the culture and I don’t meet that many people who have found their track—or in mainstream culture, either. Most people live their lives just being shoveled from one place to the next without enthusiasm or interest even. And that’s where I’m so blessed to have had my family.

I need to say something about the dissonance I mentioned. I’ve been observing the steady incursions of invasives throughout the state. They begin along roads and increase wherever there are housing or industrial developments. Every year, I see more and more land gobbled up by invasive species and it’s really disturbing. I see the wastelands we are creating right and left, and that can be pretty depressing. We’re doing so little to combat this effectively. With new homes and especially with developments planned close to wild lands, we need to have strict guidelines on what can be planted, and where, to help keep these incursions in check. Otherwise, these incredibly special places will all disappear in the next few decades.

works: Tell me about your experience here, cultivating plants that you love in this East Oakland community that has some problems.

Peter: Right. Heavily urban. Well, I’ve been connected to this community around here for thirty years now. When I first came here I worked for SAIIC—the South and Meso American Indian Information Center which was originally located in the Intertribal Friendship House on International Blvd and 5th Ave. I left the area for a long time—to live in the Oakland Hills, Portland, Oregon, Ecuador, Mexico, Venezuela, but I always came back to this area. This is where I found friends and spent a lot of time for thirty years now. I’m very comfortable here. At one o’clock in the morning, I could go anywhere around here without feeling the least bit threatened, despite having been shot at, pistol-whipped and mugged. I refuse to let those experiences limit my movement in my own neighborhood.

works: Wow. How long have you had the nursery here?

Peter: It’s been six or seven years.

works: So talk a little about that experience.

Peter: In the beginning it was kind of rough. People would jump the fence and steal plants and things from my collections. I’d get all pissed off which didn’t help at all. But, when I made friends with people on this block, they started to appreciate the beauty here and started watching over things. The kids would talk about the frogs and crickets they could hear at night. You come to this area at night and walk all around and you won’t hear frogs or crickets until you get to this block. The crickets and tree frogs, along with the birds and butterflies here at the nursery, really transform this neighborhood and there are a lot of people who appreciate it.

works: Do you have a feeling that the presence of your nursery has had a transformative influence around here?

Peter: It has transformed me just as much as I’ve transformed it, for sure.

works: This has transformed you. Are you also saying your nursery’s presence has affected people in many directions around here in a positive way?

Peter: Yes. It helps people get their priorities straight [laughs] - and nature plays a big role in that.

works: Do people drop in here and just chat?

Peter: Oh, all the time.

works: They’re curious.

Peter: Yeah. And I hate to generalize about an entire population, but Latino people tend to put a much higher value on their relationships with other people, whereas I place a higher value on my relationship to places and things. They don’t need nature the way I do. Once again, I’m speaking in very general terms. But I think this place has a calming influence on the neighborhood. It just calms everything down. The urban energy around here is absolutely frenetic at times—so much racing up and down Foothill Blvd.

A number of people from the neighborhood have begun to spend time here. The schools around here have been visiting the nursery for several years now. They just come in and walk around, eat their lunches and sometimes hang out all day. And we usually have volunteers helping out on Fridays, which is when we’re open to the public.

This can be a really tough neighborhood; somebody was shot and killed right in front of our gate just the other night. So obviously the neighborhood needs a lot more calming down! I definitely appreciate the people in the neighborhood who take steps to making it a better place for all of us. At the same time, many of us are concerned about gentrification and getting priced out of the neighborhood. I speak Spanish pretty well, which confuses people, and sometimes they ask me if I’m really a gavacho [white person]. I tell them, “That’s just on the surface. Underneath, I’m pure paisano.”[laughs] I also feel strong ties with the African-American community and have good friends there as well.

works: That’s beautiful.

Peter: Yeah. When I first came to Oakland, I lived in the kitchen with a family. We were practically on top of each other. I had a little cot in the kitchen [laughs].

works: You lived in their kitchen? [yes] How long did you do this?

Peter: Just for a couple of weeks. The only black people I had known before then was this one family near where my family lives. They were from Sri Lanka and Nigeria; they owned diamond mines there and all had their PhDs! Here it’s so different, but I’ve never felt uncomfortable or unwelcome. I talk with everyone around here - from homeless folks to the cops. I’ve always felt close to people from different cultures, races and languages. When I was growing up, we had people staying with us from many different places. We even had political refugees from El Salvador and Guatemala staying with us at times.

works: How did that happen where you had refugees staying in your home?

Peter: I think it was from our connection to the Weston Monastery in Vermont. My parents would often go there.

works: Is it Roman Catholic, Buddhist…?

Peter: My dad, several uncles and even one of my sisters went to Jesuit schools. But Weston is a Benedictine monastery. My family has very deep French Canadian roots, so I grew up around lots of Roman Catholics.

works: You mentioned earlier that you refused to be confirmed in the church.

Peter: Yeah. And my parents never pressured me, and were even supportive of my decision. My family has been tied to the Church for a very long time. Some would say that they’re religious, and I think it’s in a good way. They always encouraged us to challenge assumptions of all kinds.

works: How does that work for you?

Peter: I haven’t been to church in years, but I was pretty involved with the Jikoji Zen Center for a long time. I went on quite a few retreats with them. Even though I haven’t been part of that community for a while, it had a profound effect on who I am today.

works: And a retreat would last how long?

Peter: I did a couple of Vipassana ten-day, silent retreats. But usually I just went for weekends.

works: How were the ten-days for you?

Peter: I was really into meditating for several years. I mean, I go in and out. But lately, I haven’t been meditating much. I haven’t had time for anything but work and sleep. But I do miss it!

works: So beauty and spirituality. Is there a connection here with your love of native plants?

Peter: Oh, it’s definitely connected! But I think all my thoughts and work get much more organized when I’m meditating regularly. I say “work,” but it’s more than that; it’s what I do. If I could choose to do anything I want, on most days, I’d choose what I do for my work. I often plan my vacations around exploring and botanizing around California.

works: Do you find yourself – I was going to say thanking God - for your good fortune?

Peter: Oh, yeah. Some days, I’m bursting with gratitude [laughs]. It was thin pickings for a few years in the beginning. I really didn’t know that I could make an actual living doing what I most like to do. It was hand to mouth for quite a few years.

works: What kept you going?

Peter: It’s just that I love doing this. And I’m doing really well with it now. I have so many interesting job opportunities all the time and I’m able to share more with others, too.

works: Tell me, maybe you have some stories about how your love of native plants has influenced people. Does anyone come to mind?

Peter: Yes. Quite a few! I think I’ve had a pretty strong influence on people, especially my clients. Many of them started off with a mild interest in native plants, and are now just as gung-ho as I am.

works: So are you kind of a…

Peter: A bit of a plant guru, yes [laughs].

works: A guru – and an evangelist?

Peter: Yes, exactly! [laughing].

works: What are some of your success stories?

Peter: There are people who didn’t know a darn thing about native plants who I started a garden for, and now they’re very involved with the Native Plant Society. And some are involved with The Audubon Society, and other groups. Some of my clients keep track of all the birds and insects they see in their gardens. It’s hook, line and sinker! We have quite a few regulars who come every Friday and I really enjoy talking plants, birds, and butterflies with them.

works: That must be satisfying for you.

Peter: Very.

works: And some of these people are probably influencing others.

Peter: Oh, most definitely! You can’t really talk people into using native plants in their garden. You have to show them that it can be done, and done beautifully. It’s kind of a way of life. It’s so interesting; the people I work with end up being almost as driven as I am. I get so many calls, especially with the pandemic right now. People tell me all the time that their yards have become their sanctuaries and their salvation throughout the pandemic. Many folks say that it’s not important for them to have a beautiful garden; they want a garden that supports their local ecosystem.

For me, it’s tied inextricably to beauty. Beauty is found in everything that strongly attracts us. For me, if it’s visually beautiful, then I’m seeing harmony and harmony includes all of life in balance.

It’s not easy to make a harmonious garden. You have to have knowledge and know-how to do it, and the wherewithal to do it. But I try very hard and I love when it happens! A single garden can affect so many people – all the neighbors, and all the people who see photos of it, too. It just transforms the local community and often contributes to the greater community as well.

works: I’ve seen that with one garden near where I live. What the homeowners have done there has influenced others. It’s spread. It’s really a gift to the whole neighborhood.

Peter: Yes. It’s such a cool thing to be a part of. And it’s not me. I’m just the glove that the hand moves through.

About the Author

Richard Whittaker is the founding editor of works & conversations and West Coast editor of Parabola magazine. Peter Veilleux is the founder of East Bay Wilds and a passionate advocate for native plants.

SUBSCRIBE NOW

TO OUR MONTHLY NEWSLETTER

Share Your Comments and Reflections on this Conversation: