Interviewsand Articles

A Conversation with Dennis Ludlow -

by Richard Whittaker, May 31, 2022

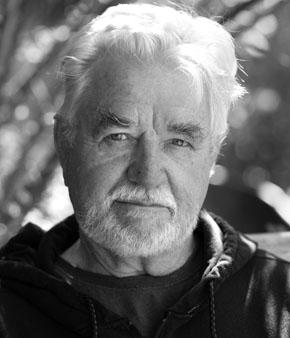

Photo: Bill Jordan

Sometimes it’s hard to pin down what triggers my wish to interview a particular individual, especially if it’s someone I’ve known for years, as is the case here. This time, though, it happened at a get together with mutual friends on an especially convivial, in-person occasion. This was after a long hiatus due to the pandemic. I hadn’t talked with Dennis in a few years and we fell into an animated conversation as we munched on our hosts’ generous assortment of goodies. He began recounting his experiences in a Zoom class he’d taken with Geoff Hoyle’s son, Dan Hoyle, about preparing a monologue around some of the characters one has met in life. As I listened, at a certain moment, it dawned on me: I have to interview my friend. It could not have been clearer. I was aware of the bones of the story that follows, and how remarkable it is, but had never thought to capture it in a conversation so others might enjoy it. And even better, it was continuing.—Richard Whittaker

San Anselmo, CA 3/28/22

Richard Whittaker: On my way over, I was thinking of my first memory of meeting you. I asked, “What do you do?” and you said, “I work for the post office.”

Dennis Ludlow: Yes. Right here in San Anselmo.

RW: And that goes back to 1970 or so.

DL: Probably. And let’s see, - It wasn’t until around ’75 that I was in the drama study group. I think it was 1977 when Sam cast me in Buried Child. Did you see that?

RW: I'm sure I did. But let’s back up. When you worked at the post office, were you a mail carrier, or what?

DL: Mail carrier. I was trying to support a family, my wife, Carol and two kids, Heather and Aaron. God that’s so long ago now! We got divorced in ‘84 and then I remarried a few years later… lord have mercy.

RW: Is that when you got together with Prartho?

DL: No. I was married for seven years to an actress, Sarah Norris, I fell in love with in a play we were doing together and my daughter, Anna came from that union. Then a couple of years later, I met Prartho [Sereno].

RW: Okay. So what led to you going into acting? Was it something you’d always wanted to do or an unexpected thing?

DL: That’s always interesting to me, too, because when I was a kid I had backyard plays for the neighborhood. I even found some slides recently from that time.

RW: Backyard plays?

DL: Well, not plays, really. It was mostly pantomime stuff. There was a guy named Stan Freberg who put out these records. He would have fun with stories like ‘St. George and the dragon’ and do the voices for all the characters. So, my friends - two or three other kids - we’d find costumes and invite all the even littler kids and their moms.

RW: And how old were you?

DL: I think it was 11 or 12.

RW: And some friends were involved?

DL: Yeah. We had a club; it was called the Daddy-O Club. Taken from a movie called Black Board Jungle.

RW: Who started it?

DL: I did. Yeah. It began when the back porch on our house caved in. My buddies and I made a fort out of the old wood. The walls were all out of plumb and everything, but we had a little table and chairs inside. The Daddy-O Club. “No Girls Allowed.” One of my favorite comic books was Little Lulu and the boys in the comic book had a clubhouse with “No Girls Allowed” over the door. So of course, we did that above our door, and for fun we did these plays.

RW: And these plays came from where?

DL: They came mostly from phonograph records and we pantomimed them. We’d find these old 78s. Here’s one to give you an idea. I remember just a few lines of it. There are two characters, the patient and a doctor. It goes like this [sings] –

“Doctor, doctor, I declare, my tickle’s on the blink and I ain’t nowhere. What do you think? Do you think the trouble is that I'm in love?”

“Yeah, Deacon. Yeah, you in love.”

And it went on like that. Can you imagine some little kid performing that?

RW: [laughs] I mean, it shows a real interest in something going way back.

DL: Yes. That was in ‘54, but cut to around 1979. I was aware that there was this drama study team that Pentland [John Pentland from the Gurdjieff Foundation in New York] had created. It was right around the time when Meetings with Remarkable Men was being filmed, or maybe they were casting; I don’t remember exactly. I always had a feeling that Pentland’s interest in drama had to do with helping out with the film or understanding more of what theater is about. I learned later that his interest in theater came way before that time.

RW: Well, and there’s probably a connection with Peter Brook there, too.

DL: Yes, Peter brought exercises, but let me go back. At the time, I started a little construction company with John Dark and Dan McDermott. John named it the “Pristine Dharma Construction Company.” [laughs] Anyway, we’re out working at one of our jobs and I hear John talking to Dan about this drama study group, and I said, “Wow, a drama group! I’d be interested in that.” John picked up on that, I guess and he must have told his wife Scarlett, who was the head of the team.

So right away I was invited into the drama study group, and it was so exciting! I'm a kind of a fearful person in a certain way. I stay away from things that put me in that state. But one of the things that really amazed me is how the love of this craft, a way of expressing something of oneself, eclipsed the fear.

We were studying the ideas of Stanislavsky, Grotowski and Peter Brook - story, voice, gesture, etc.. Scarlett Dark was the only one in the group who had theater experience and she guided us masterfully. It was not a typical acting class. It’s difficult to describe the experience, but it gave me something that I needed when I first began acting professionally.

The first play Sam Shepard cast me in was Buried Child. And those rehearsals were the first time I’d ever been in a situation working with other actors. But I had my Stanislavski book with me and it was all craft; our study group was all about craft, where performance was only one piece of the puzzle.

RW: Amazing. So all you had was from working with that little drama study team?

DL: Right. It was the direction of the team. We were learning a craft. I mean, some of the exercises we did were bringing in magic tricks to show each other.

RW: The craft of doing magic tricks?

DL: Yes, the craft of it.

RW: And a big part is learning how to lead people’s attention. Right?

DL: Yes. We didn’t get into actual magic tricks that much. It was an exercise like you say of leading the audience’s attention. Pentland came in one time when we were in the salon working. He gave us an exercise that really made a big impression, I think, on all of us. He said “Make the sound of a large ocean liner when it is releasing steam” - you know, that low sound (drops voice to deeper register). He said, “Try to make that sound. You have three chances to get it closer and closer.” That exercise of listening to what you’ve come up with, and then trying to make it better, was everything for me later for creating a character.

RW: That’s so interesting. You did your first try the best you could, and you’re listening - maybe not only listening with your ear, but maybe you’re even noticing something in the chest, the breath. Right?

DL: That’s exactly right! Because it has to come from really low, from the diaphragm.

RW: Then with that information, you try a second time. It’s a search. Right?

DL: It’s a search.

RW: What’s the search there?

DL: Well it had a lot to do with listening, you know? You’re not really sure - you’ve heard that foghorn sound before - so in listening carefully I try again to get closer to that sound. Now, finding a character is the same thing. I try voices and gestures, attitudes with my body, while listening and once in a while, something rings true for the character you’re playing. Of course, the director is there and watching. Many times, the director will say “Yeah. Go with that.” So it helps you build.

There’s that thing about actors who haven’t practiced that way of listening to their own voices - they’re always asking, “Was that good?” They’re always looking outside themselves to see whether their performance was right. There is a place for some of that, for sure, but it’s much more interesting to be listening yourself and knowing when it works and when it doesn’t.

RW: To really know.

DL: Yes.

RW: Then it’s like you inhabit it. Right?

DL: Right. And you’re always working in that direction. You get a little piece of it here, and then more after a little while longer. Richard, when you say “inhabit,” I think of the craft of inspiration. There are techniques for developing a character that helped me immensely, via inspiration. One well known way is by coming up with a history for your character. I remember when I was doing Fool for Love before going on stage I would write a love letter to the girl in the play my character came to take on a date. It worked almost every time. INSPIRATION!

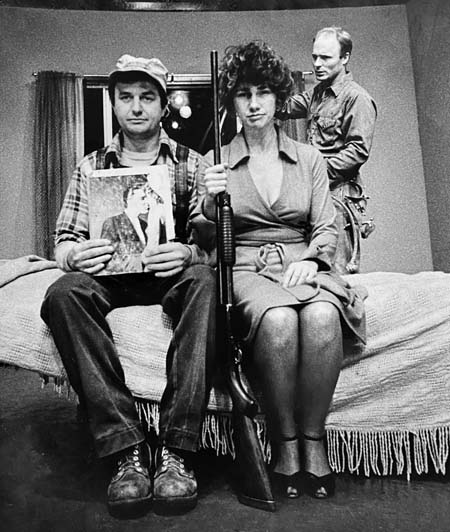

[Dennis Ludlow, Ed Harris, Kathy Baker, Will Marchetti - Fool for Love, 1983 photo - R. Valentine Atkinson]

RW: Okay. So let’s stay with this exercise that meant so much to you of making this deep sound, three tries. So the second try, you’ve been informed somewhat from the first try.

DL: Right.

RW: So this second try must have been interesting, because you’d already tried the best you could the first time. Was something possible the second time that was a little bit better or closer?

DL: Yes. I don’t know if I could say any more about it. Let me see if I can give you an example. [makes a deep sound like a Tibetan chant.] Now, that was deep, but the sound of an ocean liner would be deeper than that sound. Right?

RW: Right.

DL: So I heard that. I felt that, and now I need to go deeper if I can. So [makes a deeper sound]. See? You keep working at it like that and then…

RW: …you run up against some limits. Do you ever have a breakthrough?

DL: Well, my voice is not as flexible as it was then, I'm sure. But I do remember that when we did that exercise, I found my way to something important. It wasn’t so much about finding my limits. It was a lesson in listening to the voice - and my whole body. I learned it in such a simple way. Then I could take that with me into the theater world when I was actually doing a play.

RW: It’s so direct and immediate.

DL: Right. And there was another thing that I thought was interesting. When I started rehearsing Buried Child at the Magic Theater in Fort Mason…

RW: Can I interrupt? You’d just stepped out of this little drama study team and this was your first real acting experience? It sounds like a gigantic leap.

DL: Gigantic. No acting schools. And this was a Pulitzer prize play.

RW: I mean, come on! It’s kind of unbelievable.

DL: And that was Sam [Shepard] for you. I don’t even know when he ever saw me acting. He came to the Gurdjieff work – around 1978 or so - from London with O-Lan [Jones] and Jessie, who was a little kid. I don’t remember Sam being around when we were rehearsing. Pentland had us do portions of a Moliere play in French. Maybe Sam saw that.

RW: Wow. Did you do it in French?

DL: Yes. We had to learn French - just for a few scenes. LaVar - The Miser. We did some other stuff, too. I don’t remember Sam being in any of our study group meetings. So why he cast me, I have no idea.

So at this first rehearsal of Buried Child, here I am - this guy who’s been studying Stanislavski with our little study group. And I noticed right away that there was something different between my approach and a few of the other actors in the play. It was obvious that even though they’d gone to acting school, their main focus was on the outer. I remember how shocked I was by how these actors were so full of themselves. I was judging them, I know - and eventually that approach came around from behind to bite me - I mean the ego part started influencing me as well.

This is kind of hard to describe, but there was a point where the craft and the seeking approval became two separate things. And I was completely okay with the two things. In the beginning I was judging the others, but “now I are one.” Right? [laughs] And I was also still a craft person. So somehow, the two really harmonized. Eventually, years later, the craft part kind of dissipated, I think. Anyway, I thought that was interesting - that very beginning of rehearsing a play and coming from that influence of pure craft.

RW: That’s fascinating. Were you scared going on stage in that first play?

DL: Well, I'll tell you, the directors, Robert Woodruff, and Sam - they worked together closely during rehearsal. They gave me all the confidence I needed to bridge the fear. Of course, yeah, going on stage can be frightening. But fear can be put aside if you have something that trumps it, you know.

[Dennis Ludlow, Kathy Baker, Ed Harris in Fool for Love, 1983, photo - R. Valentine Atkinson]

RW: I'm stuck Dennis, on this great leap from this little team to the real deal - and how something can trump fear. Earlier, you said, “I'm a fearful guy,” and I can relate to that. But as you say, there are some things that can trump fear. They’re priceless.

DL: Yes. I think I told you about that storytelling class I took recently?

RW: Yes, you were telling me about that.

DL: It was a Zoom class with an amazing new writer/actor, Dan Hoyle; he’s Geoff Hoyle’s son. Geoff was one of the best clowns I’ve ever witnessed. There were eight people in Dan’s class. The study was on writing and performing. We met once a week for eight weeks, a three-hour class. I had a love/hate experience in each and every class. I'm still trying to figure out why I had such a reaction. I did not want to continue and did at the same time.

The class made me see how locked up inside I am. The others, young and old were full of energy and seemed comfortable trying things. I don’t know if you’ve ever felt this way, Richard. Do you ever feel self-conscious when you’re dancing with a lot of people around? My attention is not on the joy and freedom of moving. I’m self-conscious. It’s not a comfortable feeling. Well, that’s what it felt like. I just could not break out of that prison. I think it would have been better if it had not been on Zoom. Practically every class, when it was over, I’d tell Prartho “I'm done with this! I'm just going to quit!”

Then knowing how we all have many “I”s, I just waited for a new one to come up in the morning; and sure enough, there it was. I stayed with it all the way through. At one point this back and forth - YES! NO! NO! YES! - became interesting. It was interesting to see these two contradictory things side-by-side. It was hard to stay with it, and yet there is some basic thing about holding contradictions that I'm just kind of waking up to.

RW: Right. That could be an interesting conversation in itself. But going back to the craft of acting – I’m thinking you touched on a key thing there when you were talking about finding the character and you used the word “inspiration.” To me, it sounds like a door opening into the real as opposed to being stuck in something that’s not real.

DL: I'm not sure how to relate to that, the real and the unreal. But that whole subject of building a character… You’re given a character, take Fool for Love— I think I heard this from John [Dark], that Sam wrote that part for me—Martin, the gardener character, a simple guy.* He wears suspenders, probably. He was coming over to take this girl on a date. But this rodeo guy, who Ed Harris played, just barges in on this girl. At first we think she’s an old girlfriend - Kathy Baker played her. The first half of the play is kind of like Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? There was a lot of fighting and pushing… Anyway, the girl didn’t want anything to do with the Ed Harris character who is just an asshole. Also onstage, in a corner, is the girl’s father. Will Marchetti played that character, an observer, who every once in a while, will say something.

RW: To the audience?

DL: Right. Then they’re having a fight, and the lights go out just when my character, Martin, shows up. He barges through the door because he thinks this girl that he likes is getting molested and he throws the rodeo guy down.

So here’s a character that I certainly could relate to, a guy who works on the land with his hands, and kind of an essential type with not much of a personality. I remember working on that character. Like I said before, you develop a history on your own. So I’d write stuff before the play every night - new episodes of what I'm like, the character, is like - and that would inspire something to be more real on stage. You know, the audience is a big part of the energy. It comes from them listening and you need to not let that energy distract you from your character and lines.

There’s a whole mysterious thing that happens. You’ve probably experienced that where the audience is feeding you in a very mysterious way. You’re not always in character. There are times where you slip out of it and all of a sudden it’s Dennis.

I needed inspiration in order to do a good job for a play. It was my downfall, actually, in the end because I didn’t really have any technique. Technique is learned in acting schools and I didn’t have much of that to fall back on. It was always inspiration. I always tried to find ways to be inspired.

When you feel the character, it’s exhilarating because you are who you are and the character is in there, too, and you know somehow that the energy of the line and the connection with the other actor and the audience is right. It’s incomparable.

It was fantastic working with Ed Harris because he was there. We both just loved working with each other back and forth, the two of us. That’s what we were doing; we were playing: two characters, and our own selves, too. I just remember that wonderful feeling. Can I tell you how I met Ed?

RW: Please.

DL: This was before rehearsal started for Fool for Love. There was a bar, Tosca’s, in North Beach across from the City Lights Book Store. It’s not there anymore.

RW: I remember the place.

DL: Well, the woman who owned that bar, Jeanette, was a real Magic Theater contributor. A lot of people went over there for drinks after the show. There was a party just before rehearsals started for Fool For Love. It was very crowded and I remember seeing Mickey Rourke having a drink at the bar, do you remember him?

RW: Just from seeing him in a couple of movies.

DL: I’d just seen that movie Diner that he was in. I remember going up to him and saying, “Oh, my God. I loved that character that you created in Diner.” And he goes, “Uh, yeah,” in that falsetto voice of his. He gave me his character from Diner, right? And it was like “Okay. Sorry to bother you.”

Anyway, a few minutes later, Ed comes in, and Sam is there. Sam says, “Ed, here’s the guy that’s playing Martin.” Ordinarily, you reach out your hand, right? Do you know what Ed does? He jumps up in the air and wraps his legs around my waist.

RW: Oh my gosh.

DL: So I was holding him up and he looks right in my eyes and says, “Don’t think I’m going to be easy on you.”

RW: Wow! That’s a wild thing to do. Did you get along with him okay?

DL: It is, yeah. What a shocker. And it’s called breaking the ice. We became the best of friends.

RW: You know at this late period of my life, I have had a few experiences with that audience thing where I know I've got the audience with me. It’s like you’re saying.

DL: It’s a feeling.

RW: Right. It makes it possible for something to be alive and giving the best you’ve got, somehow. It’s not an ego thing.

DL: No. It’s playing; it’s really playing. It’s what the word means, I think.

RW: You know, I interviewed Murray Mednick and he talked about those moments on stage when it’s right. He called it “surfing on the audience’s attention.” So, how many plays have you been in would you say?

DL: Nine or ten, there haven’t been that many. I did write a play. It’s unfinished. I worked on it some in that Dan Hoyle workshop I was telling you about.

RW: Say more.

DL: It’s about a guy who lives alone, who lives in his fantasy world. He’s a mask carver. The play opens with him standing on a chair, and he’s wearing a long navy coat, a captain’s hat and he’s talking to the audience about how he’s a submarine captain. And he walks people through his sub. Anyway, I really like it. I mean, I developed the beginning of it by means of improvisation many years ago and performed it at The Marsh [in San Francisco].

RW: I remember. I saw it. But I forget what you called it.

DL: Sinking.

RW: And you were working with Kathleen Cramer who was also in some of these plays at the Magic Theater, right?

DL: Right. She directed it, and she wrote a song for the opening. She’s another wonderful director. Actually more than half of that play was autobiographical. It was about what I went through when my mother died. I’d sink, you know, when things got too emotional. I sank and became this submarine captain. But I had so much fun developing the character in this latest workshop with Dan, because there were new things appearing. I started writing the play as just this guy, Walter, who lives in this apartment. He has a hat rack with all kinds of hats. He’s doing these submarine fantasy things and then there’s a knock on the door. Walter walks to the door and asks, “Who is it?”

“It’s Frank.”

“Just a minute, Frank” he says, putting on a hat for dealing with this person who might be complaining about the loud noise he’s making. It’s back and forth, like that, just putting on different hats for different people.

Then his daughter shows up and she’s concerned about his health. It comes out that he’s been diagnosed to die in a few months, and he’s denying it. His daughter is trying to get him ready for the inevitable. When the conversation gets too much for him he sinks into a fantasy. Do you know The Katha Upanishad and Nachiketa around the question of death?

RW: I’ve read it, but I can’t call it back at the moment, exactly.

DL: Well the young Nachiketa, through some experiences, ends up face to face with the god of Death. In the Katha Upanishad, he wants to know what happens after you die. I came up with this thing where somehow the stage is split, so there’s this back and forth between the dream world and this world. Death says, “You’ve forgotten me, Nachiketa.” Nachiketa says, “I don’t know who you’re talking to. My name isn’t Nachiketa; it’s Walter.”

Walter can’t see Death. He’s frozen with his back to Death. He can only move his head. It’s a feature of the play. Eventually, he will be able to move around and face the god of Death. And the one playing Walter’s daughter is there, also playing Death.

RW: She’s bringing the reality to him.

DL: Right. Eventually he comes back to the present. I haven’t taken it much further than that.

RW: So this is the play you’ve continued to develop all these years that you originally brought to The Marsh. [yes] That’s a fascinating thing.

DL: I'm glad you think so. The death part of it is all real, unknown territory, you know. That’s an area many people avoid thinking about, though at my age, it’s much more relevant.

RW: We’re being reminded often.

DL: God, yeah. Especially being in the community where a lot of people are dying.

RW: You know, Dennis, I feel that we should have given ourselves a lot longer for this conversation.

DL: I know what you mean. I had no idea. Last night I was saying to Prartho, “Oh, man, I don’t think I'm going to have anything to say to him.”

RW: Your life has been so unusual, being this quiet guy and then finding yourself onstage at the Magic Theater, meeting well-known actors and performing in plays that are very highly-regarded. Say a little about your relationship with Sam Shepard.

DL: Well, it’s true. It was an amazing time when we first met. Sam, O-Lan and Jessie were living in the same house in Mill Valley with John and Scarlett Dark, who were my close friends. That way I got to know Sam well before my introduction to theatre. He knew that I was a carpenter and hired me to build fences at his ranch in Rohnert Park. It was one of the best jobs I ever had. I put a good mile of fences up for his horses around his property and did a lot of carpentry work around his place. I even built him a barn for his horses.

During those first few years after arriving in Marin with his family he wrote two or three plays for the Magic Theatre. I remember going to them. O-Lan was in most of them and I just remember the feeling I had watching those plays like, “God! I would just love to be a part of this!” And at that time, I wasn’t yet involved in the study group, so I had no idea that I’d be on stage myself in another year or two.

But as a director - I mean, I haven’t had that many directors - but Sam was the all-time best who I've ever worked with. Well, he wrote the play and that was a big part of it, but then he encouraged you to try all these different things. I think that, for most actors, when you begin rehearsal, you’re stiff as a board, you’re scared, you’re worrying like crazy about what others think, because basically, you’re making a fool of yourself every day. Then eventually that falls aside and you start playing. Sam was able to allow that process and then, when you hit something that connected with his vision, he’d let you know. That’s how you were kind of building something piece-by-piece. He never did that thing where he’d tell you how to do it.

RW: He didn’t do that?

DL: Right. Some directors will say, “Try it this way,” and proceed to say the lines the way he or she wanted it to be said - which sometimes is helpful. But Sam never did that when he was directing. He always let the actor discover the character on his own - and he knew that actors need to learn slowly. That’s important. Some actors, when they go for an audition, the thing they do at the audition, they’re still doing on opening night. That’s giving up a lot of the fun, because building a character, for me, took the whole two months or whatever the rehearsal time was, to get to a place where I was comfortable with what I was doing. Anyway, Sam was great in that regard.

RW: What are some of the most memorable moments in theater over the years of your involvement?

DL: Well, one was just a fun moment working a scene on Fool for Love. We were rehearsing at a place on Valencia Street in San Francisco working on a scene where Ed [Harris] was on the floor, and he’s pretending his legs don’t work. I came to rehearsal wearing worn-out Levi’s that day. This character Ed’s playing is trying to get me to relax because my entrance was highly emotional. So he drags his body towards me. He’s down there looking up at me and we’re having this dialogue.

I had one of those keychain things that you pull out and the keys zip back, and he reaches up and grabs it. We got into this little tussle, and that became part of the play. He was yanking my chain [laughs]. But at this particular rehearsal he caught his thumb on my Levi’s and ripped them, and it turned into another whole thing.

Pretty soon my pants were just in shreds and we were all laughing. That was such a funny rehearsal because we all went with it. When it was over, Sam said, “Man! I’d love to do that every night! But that’s too much to figure out.” It was a great moment.

Here's another one. These are all discovery-of-character things that were really exciting. In Buried Child, I played this retired football player, Tilden, kind of a burned-out guy on alcohol and drugs. He was living at home with his mom and dad and was always out in back. Buried Child had to do with a baby that was buried out there and also about the loss of innocence. It was an illegitimate baby between my character and my mother, and it was a big secret - until it wasn’t.

RW: You mean it was incest?

DL: Yes, my character’s mother’s husband is Dodge - this grumpy old guy, who is on stage all the time. The character I played came in from time to time from the backyard carrying arms full of corn. In this scene this young, spirited girl who is the girl friend of Dodge’s grandson is having a conversation with Tilden. During rehearsal while I was talking to her, I started slamming the green tops of the carrots on a stool - a gesture of nervousness talking to a beautiful women. I remember Robert, the director, always got excited when there was something he really liked; he’d run up to the stage laughing and carrying on, and that carrot slamming became part of the play.

RW: So you did that on an impulse in the moment and the director loved it.

DL: Yeah. That was an example of discovering the character.

RW: It’s interesting these two stories both happened in rehearsal. So rehearsing must have been kind of a gas at times.

DL: I've always said to friends that the rehearsal process is the best part. Doing the performance in front of an audience is hard to beat, but rehearsing is, too.

RW: Were you in touch at all with Sam later in his life?

DL: A few times. The last time I saw him was after I heard he was coming out to do his play The Late Henry Moss with Jim Gammon, Sean Penn, Nick Nolte, Woody Harrelson and Cheech Marin. I called and said, “Hey, when you’re out here rehearsing, call me and we can go out and get a burrito or something.” A week later, I got a phone call from casting telling me that Sam wanted me to play a role in that play - a part with no lines. I was one of two guys from the funeral home to take the body of Henry Moss off stage. That was all I thought I was responsible for, at least until the first rehearsal, when they hand me the contract. It said I was to understudy Nick Nolte’s character and Jim Gammon’s character, who played Henry Moss. They’re on stage the whole time. I told the stage manager there’s no way I was going to be able to learn all those lines. There was no response. Then I told Sam. He said, “Don’t worry about it, you’ll get it.” So I reluctantly signed the contract. By opening night, I had Nick Nolte’s lines down, but I hadn’t even started on Gammon’s. The Magic Theater director got word I was that far behind, and I was fired. I kept on doing that removing-the-body thing, but it really got me - my confidence, you know.

Then after rehearsal, Sam left. He didn’t say good-bye to anybody. I remember Sean Penn saying, “Everybody has a dark side, but walking out without saying anything to the cast is not good.”

But in a way, that was Sam. He just did whatever he wanted to do. I've seen him be served a beautiful meal with lamb chops and take two bites of his potatoes and then shove the whole plate aside. Do you know what I mean? That kind of attitude was infectious, in a way. He wasn’t a big worrier about what other people thought. So then there was that movie Shepard & Dark. You saw that?

RW: I did.

DL: Right after that John and Sam had a falling out. I think Sam went out of his way to try to patch it up, but John was holding strong. Then Sam gets ALS and went way inside, as you imagine he would. At that point, he was living up in Healdsburg with Jessie and his wife for a while. He wanted to stay there. And during that time I heard the Magic Theater was doing something to honor Sam. You know, he put that theater on the map back in the old days. So I called and talked to Jessie. I said, “Hey, I was just wondering if Sam would be interested in going to this thing the Magic Theater is doing. I’d be happy to take him.”

Jessie said, “I really don’t think he’d be interested, but I'll ask him.” And that was the last time I ever had any even indirect connection with him.

RW: Who are the memorable people you’ve met in your years of acting who you might want to say something about?

DL: I don’t know if this would be interesting - it’s been a few years now - but Ed Harris and his wife, Amy, were cast in a Broadway show of Buried Child. Ed was now playing Dodge, the old, cranky guy who’s the father. We saw that it was coming to New York and Prartho says “Why don’t we go see it?” So, I contacted Ed and told him we were coming. It was great to see the play again after 30 years. Ed did an amazing Dodge character and Amy’s mother character was flawless.

After the play we met, now two old guys for real. Ed said, “Let’s have a drink across the street.” So we did. All these years had passed since we’d done Fool for Love together. I’d seen him in movies and plays, and now here he was - an old guy, and I'm an old guy. He and Amy had a child who was in her twenties and just getting into theater herself. But it was like no time had passed. Of course, the ease had a lot to do with Ed because he was always a pretty relaxed guy one-on-one.

RW: I remember quite a few years ago a conversation where you expressed interest in improvisation, and also in Peter Brook. Is there anything you’d like to say about Peter Brook?

DL: Yes. One thing is that whenever his ensemble came to town they had one-day workshops. I remember one - I don’t think he was even there; his students ran the exercises. There were a bunch of people there like me and we did these exercises - kind of typical and not so typical - theater exercises. One I remember was where two people walk toward each other, pass by each other feeling the tension - that kind of stuff.

RW: Right.

DL: So there was that. I mean, I worshipped the guy, basically. I have all of the Peter Brook books that I've read through the years.

Once on a weekend, Kathleen Cramer, Joyce Irvine, both who are professional actors, and I met with Brook. I remember saying something about how in the old drama study group, we studied the ideas of Grotowski, Stanislavsky and his, too. I remember him saying, “You can forget about Stanislavsky and Grotowski.” So you subtract those two and who do you have?

Did you ever see the video of his, Tightrope? He has these actors, really good actors - stage actors mainly - pretend they’re walking on a tightrope, but really they’re walking on the floor. And it’s so interesting to see how people are pretending that they’re on this thing, right? Then he gave his impressions. He’s still at it isn’t he?

RW: By all that I've heard, yes - in spite of his diminished state. He’s in his nineties and almost blind. I’d read Margaret Croyden’s book Conversations with Peter Brook, which is really great. In one part he talked about taking his group to some out-of-way place to meet indigenous people. None of his group spoke a word of their language. Then they performed, on the spot - all utterly in the moment. He was interested in seeing how much could be communicated, I think, in such a situation. I mean, what an amazing concept. Who would come up with something like that? And then to really explore it - something so unthinkable, in a way. Apparently the experience was just full of incredible stuff for him and his troupe. To me, that’s so interesting.

DL: I know. There’s another story where when they were developing a piece, they would do it in front of grade school kids because the kids don’t lie about losing interest. If they lose interest you know it. They start fiddling around and so on.

RW: Right. You don’t want to settle for a good imitation of being interested.

DL: Yeah, yeah. You know another story that really influenced me and got me into this mask stuff, Peter Brook brought his troupe to Bali. He asked this Balinese dancer and carver to lay out all these masks on a table. His troupe just went in and grabbed these masks, put them on and started joking around doing all kinds of comic bits with them.

Peter looked over at the carver/dancer and saw the man was mortified. He could see it in his face. Then Peter knew they’d gone too far. The way to work with a mask of this caliber - you put a mask on and look at yourself in a mirror, and let the mask take your body, your voice, attitude - let its expression act through you.

RW: Peter Brook is a sort of real guide for what theater and acting is really about, you’d say?

DL: Yes. He describes what a good actor is and I, of course, always wanted his description to be a description of me [laughs]. One of the things he said - and I just latched onto it - was that good actors are generally shy people.

RW: Interesting.

DL: I've always been very shy.

RW: You’re a shy person? [mock surprise] I'm a shy person, too! Although I'm a somewhat recovered shy person.

DL: [laughs] Yeah, I love that recovered.

RW: No, I've been doing all this walking - I think I chatted with you about that. I'll walk like an hour or two hours in neighborhoods I haven’t been in. I'm always interested in encounters with strangers. So just yesterday I was walking with this interesting young man [Reyn Aubrey]. We were passing this house up in the Berkeley hills. On the front porch, there are these two big figures in coats of armor facing each other. I’d seen them on an earlier walk and had wanted to take a photo, but I didn’t want just walk up on this private property. But here were three people in the front yard, so I just addressed them.

DL: What did you say?

RW: Is this your place? Do you live here? I had this good energy. “We don’t live here, but we know the guy who does. Yeah, sure, go on up and take a photo.” So all of a sudden, this whole thing was happening. Everybody was chatting in good spirits.

DL: I know what you mean, yeah.

RW: It all just bloomed on the spot.

DL: Especially when it’s intentional, it’s even more strong, right?

RW: Well, it’s interesting you brought that up because for me, these things are intentional. I mean, an impulse appears, but I have a choice. Am I too scared? Should I seize the moment? In a situation like that, when I say “Yes,” it’s intentional.

DL: Yes.

RW: So say more about how it’s even stronger when it’s intentional.

DL: I've had the same experience. I’ll walk at Lake Lagunitas, and most of the time, Joe [Mc Guire] and I meet up there. We’ll walk and talk about ideas - Vedanta ideas sometimes. He’s like what you’re saying - with almost everybody we pass on the trail, he’ll say something. He’s a recovered shy person as well. He’d say that. He makes an effort of being friendly with people. I do it once in a while. I usually don’t really want to, but I kind of force myself. I mean, I always say hello, but going into conversation, I'm not apt to do that.

I was up there yesterday walking on my own. There were two ways to get back down to my car. I looked down the way I like to go where at the far end there’s a bench, and I saw that somebody was sitting there. Talk about being shy, or whatever it is? Fearful? I saw this person. I didn’t know if it was a woman or a man, but I heard my thought: “I don’t want to have any connection with this human being.” And I was about to go the other way, the way I didn’t want to go. Then another thought came up, “What are you doing? You want to go this way and you mean you’re not going to because somebody is there? That’s silly.”

So, I did. I was wearing this Pendleton jacket that’s got a buffalo design all over it; it’s kind of ‘Indian blanket’ looking. It’s a little “out there,” which isn’t my usual thing, but I love this jacket. So I was getting closer and closer to this guy sitting on the bench, and I was going to ignore the guy, right? But he turns my way and says, “Hello, Chief!” He went into this whole thing about, “Oh, boy, I'm going to have to go back to my life. I’d just like to sit up here forever.”

I said, “Yeah. Right. I know what you mean.” It was a perfect situation to just get into a conversation, but I found myself moving away. The last thing I said was, “Have a good one.”

“Yeah, you too, Sir,” he said—he called me “Sir.”

Like your experience in the Berkeley hills, Richard—some kind of expansion of awareness just happens when you go beyond your comfort zone. You know, there’s something profound about intention. I've always thought when you have an intention it turns on a light somehow.

*After our conversation, Dennis dug into his papers and found a letter dated Oct. 8, 2013 from Shepard. In regard to casting Dennis in Buried Child, first performed at the Magic Theater in San Francisco in 1978, he writes, “You don’t have to thank me for the role of Tilden. I cast you because I thought you were completely unique and possessed a certain kind of innocence no other actor was capable of.”

About the Author

Richard Whittaker is the founding editor of works & conversations and West Coast editor of Parabola magazine.

Dennis Ludlow is an actor, designer/builder and student of traditional mask-carving / storytelling. He lives in Marin County in the Bay Area with his wife, Prartho Sereno.

SUBSCRIBE NOW

TO OUR MONTHLY NEWSLETTER

Share Your Comments and Reflections on this Conversation:

On Apr 2, 2024 Halldor wrote:

Thank you for taking us along, wonderful to revisit the places and names that bring so many good feelings back insideOn Mar 14, 2024 Mary Curtis Ratcliff wrote:

Richard,I just finished your interview with Dennis Ludlow and found it lively, engaging and very educational about the craft of acting and learning a role. Well done!