Interviewsand Articles

A Conversation with Zoo Cain: My Real Name

by Richard Hunt, Sep 3, 2022

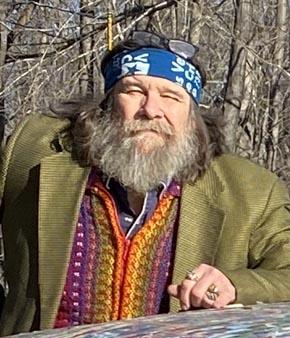

Photos by Elizabeth Hunt

When first approaching Zoo Cain’s workspace, I knew immediately that I would be spending time with someone unique—a person with a rare perspective on life. What began at an early age as an escape from a dysfunctional family environment has evolved into a lifelong passion for form and color. I entered the one hundred fifty year-old New England post-and-beam barn he calls his studio in Maine. The workspace, sunlit and cluttered with a hoard of collected objects and art supplies, features both in-process and finished works. He was busy, as I later learn he always is, working on a commission piece: the body of a custom electric guitar. After a brief greeting, we settle into a comfortable living space in the loft where he works. —Richard Hunt

works: Thanks for taking time to chat with us today. Before we begin, I have to ask, is Zoo your real name?

Zoo Cain: Zoo has been my real name since I was thirteen. Up until then it was Louis Philip Cousineau II. I hated my dad and my dad hated me. Why we were called the same name was beyond my comprehension.

So at thirteen, I’m raising hell up at a quarry in Topsham, Maine. Thirteen years old and already drinking. I was a very gay drinker. I loved to whoop it up. I was big at whooping it up! So I’m on top of a cop car, dancing on the roof. The cop pointed at me and yelled out, “I can’t arrest you. You belong in a zoo!”

My friends were all laughing and began calling me “Zoo.” I’ve been Zoo ever since, which is a long time! I never felt a connection to my birth name. I resonate with the name Zoo. So yes, Zoo is my real name. It’s on my driver’s license. It’s on my Social Security card. The Veterans Administration knows me as Zoo. At least people can pronounce and spell my name correctly now. My last name now is Cain. This is not a biblical reference. Cain means “creating with the help of God.” Zoo Cain is a simple name and I believe in keeping life simple.

works: Can you tell us a little more about your formative years?

Zoo: My formative years were horrendous. By the time I was two, I realized my father was not a nice man. I realized he had a hair-trigger temper. By the time I was five, I was trying to escape. When my old man and I started to get into it—and I was getting the short end of the stick—my mother would be in a dark corner, wringing her hands. I would just take off.

I began to run away. So my mom started giving me crayons and coloring books and colored pencils. She began doing pencil drawings of Woody Woodpecker and Popeye for me. She was pretty good with sketches. She had creativity in her that got stifled ‘cuz she raised six kids, but she never stopped giving me things for an outlet to get my kicks. She was trying to lessen the torment that was going on with me. As a kid, I would do anything I was capable of creatively to leave my mark in the world. Something as simple as making a design in the snow by dragging a stick through it. When I was young, I remember going gaga when I saw gas or oil in a puddle of water. Oh my God! The colors!

works: So good or bad, it’s safe to say your father had some influence in your creativity early on.

Zoo: When I was ten years old I got a brand new bicycle, a J. C. Higgins. I painted the whole thing. I just poured paint on it. My old man almost lost his mind. He couldn’t believe it. So I guess I was always creating art without knowing it. I didn’t realize I was creating art until I was twenty-three. I was in a gallery and was looking at this canvas. It was all white and textured. It looked like a mountaintop in the Alps. I remember thinking, “What the hell is that?”

The guy next to me said, “That’s a painting.” I’d never seen anything like that before. I started to explore different mediums like sculpture with wood, and I began looking at Louise Nevelson’s work and drawing similarities to what I was doing. The first time I saw Robert Rauschenberg’s work it reminded me of what I was doing at the time. It felt very familiar. I was doing a lot of experimenting, which is a wonderful way to create art. It pours from your fingertips. For these reasons, I would not trade my tough upbringing and relationship with my father for anything.

My father was also a guy who always had a pencil and a ruler with him. That kind of rubbed off on me. Even as we speak, I’m sitting here with a pencil tucked behind my ear. So in effect I was turning my agony into something good. To this day, no matter what the issue is, I see the silver lining and the rainbow—always! It’s all this angst, this tremendous, traumatic childhood that turned gray into great creativity. I could have gone into the corporate world and done fairly well, but I chose to stay with colored pencils and paints.

works: It strikes me that your art is vibrant, uplifting, full of color, full of life. And it seems as though it’s all driven by channeling angst. Was that the catalyst?

Zoo: Exactly! I made beauty out of it. Coming from a dark place and breaking through that, I chose to celebrate life. Every day for me is very mystical. For example, Mother Nature, which is all around us, is the big picture. If you’re at peace and in a good place, and seeing the whole picture rather than the small picture, and getting out of your head a little bit, that’s what it’s all about.

Right now, just looking at you, I see a magnificent example of a human being. I see the art around you. I see the beams and the beautiful wood siding of the barn where we’re sitting, and the collage material here on the table with the colored pencils. I’m taking it all in. I’m in the moment. I’m not thinking about tomorrow or what I’m going to be doing an hour from now. My art is basically a celebration of all of that. A celebration of you and the other things I just mentioned, along with everything in the universe.

works: So in essence, you see art in everything. It’s a perception thing.

Zoo: Absolutely, I do. And I see ways to create things from other things. I’m looking at that box of colored pencils and thinking, I can do a thousand pieces of art with those pencils. All I have to do is find some surfaces.

works: So you were creative as a kid. Were you always attracted to art?

Zoo: I was never formally introduced to art. I only made it through eighth grade in school. And during those eight years I learned nothing—and I mean nothing! Zip! I didn’t learn the alphabet, or the months of the year. Nothing. I remember looking out the window and thinking, “What am I doing in this place? I should be outside.”

After dealing with my father, I could not relate to any authority. He completely ruined authority figures for me. I couldn’t pay attention. I got through eighth grade and I was out the door!

As I mentioned, when I was twenty-three, I saw a painting of mountains in a gallery. That’s when I began to get serious about art. I started getting canvases and boards and actually began thinking about creating art.

works: You began to develop a technique in your twenties. Had you had any formal art classes or coaching in your younger years?

Zoo: I may have, but I have no recollection. You have to understand that every minute in school felt excruciating. It was like being in a prison. I was drawn to things I saw outside—oil in a puddle and the rainbow of colors it created, the color of birds or flowers. Unabashed beauty! Almost shocking.

COVID forced me to look even closer at nature. I am ecstatic about nature. I am especially drawn to trees and want to help save them. If I see a tree being strangled by vines or another tree leaning on one, I will try to save that tree. I do a lot of that.

works: I’d like to dive in further to what inspires you creatively. How do you approach the process? Do you begin with an image in your mind? A mental model? Or does this develop as you are working?

Zoo: I go through life with a third eye. I can be inspired by anything: something I saw in a movie, how a character acts, walks, relates to other characters—even something as simple as a gate on a neighbor’s fence. A lot of things stick in my mind that make me think I could create for another three lifetimes. At 69, I’m eventually going to run out of time, so I’m lobbying to work on rainbows when I get to the other side. And I’m definitely creating with the spirit world all around me. I have a fleet of muses and everything has been going well with them. They love what I do. For 46 years it’s been “pedal to the metal” creating art. Prior to that I was creating art, but didn’t know it.

The spirit world is very prevalent in my mind. My mind is open. And like I said before, the third eye is always open. I am totally open. For this reason, I’m able to keep creating. There are no obstacles. There is nothing in my way that I can’t soar over. Like an eagle, I just soar over obstacles. The spirit world is happy with what I am doing.

works: Is it fair to describe this as an unencumbered perception?

Zoo: Yes, that’s a great way to put it.

works: Is there a specific artist that inspires you?

Zoo: I think the artist whose work I relate to the most is Maria Helena Vieira da Silva. I love her work. Of course I love Picasso. I love Robert Rauschenberg, Louise Nevelson. Alberto Giacometti… I love that guy’s work! I would add Polly Brown. I dig Jackson Pollock, Jasper Johns—all those cats from the fifties.

I don’t like much of what I see now. I mean, no way! When you see a 50-million-dollar bubble of a pig or a flying goat, I’m not there. Another influence would be Frank Stella’s early work. I’m very rudimentary.

I like the artists that were painting with five- or six-inch brushes. Willem de Kooning is another inspiration. Francis Bacon is another great inspiration. In terms of collages, I would say Peter Beard. Very sad… He died a little less than two years ago. Apparently of dementia. Beard was very focused on the environment. He was a political artist, but I love his style. [Zoo reaches for a copy of Beard’s Zara Tales.] Even though we’re destroying the planet, I tend to celebrate life rather than focus on a political statement. I also should mention Van Gogh. I absolutely love the guy and feel a kinship with him. Again I’ll mention Maria Helena Vieira da Silva. An incredible talent, but not getting the credit she deserves. Her art is so stunning!

works: I’ve heard people describe you as a man of color. You seem to be drawn to vibrant colors. Your art, your clothing, even your vehicle reflect that. What inspires that?

Zoo: I think the flowers and the birds and nature. There’s really not a color I don’t like. I mean, I used to drive around with another Portland [Maine] artist and look out at fields. He would always comment about the hues of color in a field. I wasn’t seeing it. I would ask, “Michael, what the hell is going on with you?” But now I see different nuances of a field. Fields kick my ass! But I had to develop that. I had to actually get my mind more open to that. I use all the colors, but am drawn to vibrancy. I always carry a red pencil. It never leaves my side. A lot of things get colored some shade of red.

works: Specifically about your art, how would you describe your style?

Zoo: I’d call it “mixed-up media.” A lot of people describe their work as mixed media. My work is “mixed-up media.” As an example, at twenty-four

I did my first canvas. I had some geometric shapes that were all colorful. I can visualize it as I sit here: orange, red, purple, green. Very bright and vibrant and the colors all had their space. Then I had to do the bravest thing I had done up to that point. Keep in mind, up to that point in my life, I had done a lot of “brave” but crazy things. I took an old Fudgesicle wrapper and stuck it right in the middle of the canvas. This was a big canvas. Anyone else would say I just ruined that canvas. Then I took a palette knife and ran some oil paint down the sides of the wrapper to adhere it to the surface. From that point on I felt free to do anything I wanted. I freed myself from any constraints I felt in approaching my art.

Before that I was doing canvases with different shapes and colors similar to Paul Klee—very geometric, inside the lines. The Fudgesicle wrapper took me outside that boundary. I lost all of my fear. It was like jumping off the highest cliff I could imagine. And I’ve jumped off my share of cliffs. This felt like jumping into the Grand Canyon. After that I was fearless. Polly Brown visited my studio. She looked around and said, “You aren’t afraid to do anything, are you?” It was a major turning point that, had it not happened, may have resulted in me being a strictly geometric artist. I then began trying different mediums.

I began doing wood sculptures, making license plate art, drawing and painting on wood and canvas and creating collages. During the past 20 or so months I’ve focused mostly on collage. I had a lot of inventory and needed to get smaller to save space. With collages I could fill shelves rather than barns. You can mix so many worlds in a collage. It’s infinite what you can create with them. I broke the sound barrier years ago. Creating is so natural for me now. I never have a block. I’m on a roll. This started as a little snowball at the top of a hill and rolled into an avalanche—an avalanche of artwork. I’d estimate I’ve done ten to twelve thousand pieces. I used to keep count. One year I started 725 pieces and completed over 500 of them. [Zoo picks up a circular piece of scrap metal with an open middle, and holds it up.] Look at this perfect piece of work. I’ve always been able to see art in odd places, even as a child. I guess I’ve been lucky in that way—although my wife might not appreciate me bringing home old mufflers and whatever.

works: You’ve done a fair amount of pop art using license plates. How did that evolve?

Zoo: I love license plates. I always have. You go into a garage and see a few on the wall—I’ve always loved that. So I began cutting the plates into various shapes and blending them into my abstract pieces. Then I began cutting the letters and numbers and joining them together to form words or messages. I’ve pumped out a lot of license plate art. People mail me plates from all over. I don’t cut plates unless they’re fairly modern. I don’t destroy antiques.

works: Is it fair to say the license plate art has been an outlet for you to convey your thoughts on political or social issues?

Zoo: No, I don’t think so. A lot of it stems from my life in the ‘70s. I see one behind you that says “Tibet.” Another says “Sting” and another says “Queen,” “BB King,” “Bob Dylan” and “Dalai Lama.” I dream a lot and Dylan often appears in my dreams, so I’ve done a few pieces of him. We share the same birthday and have the same vibe going on. I also make plates of places like Hong Kong or Afghanistan.

The plates are more impulsive and less about wanting to convey a political message. I’m celebrating things I appreciate. A specific word comes to mind and I’ll shuffle through over a 100 plates to get the letters or numbers I’m looking for. Keep in mind I may be working on 50 different projects and bounce from one to another. Right now I’m working on 10 collages, several plates, and several canvases, all in different stages.

I will say I don’t like commission work. I might have someone who owns a piece, call from Florida and say, “A friend loves this piece—can you do one for her?” Oh my God! I can’t duplicate my art!

works: A few years back a film producer released a documentary about your life both as an artist and as an incredibly generous and giving human. There’s a scene in the film where you gather some random items —a hammer, pieces of cut up license plates, a hubcap, et cetera—and arrange them in an orderly design on the floor. You then stand back and proclaim, “There. It’s finished. It’s perfect.” The scene was compelling, much like ephemeral art. The temporary nature of that arrangement of objects made me wonder if your military experience or your relationship with your father was an influence.

Zoo: It wasn’t symbolic of what I typically create. It’s not installation art. My work is permanent art. I fix things on things. In more recent license plate art, I’m using empty aluminum cans, flattening them down, and placing them behind numbers or letters. This brings a glow or highlights a character. So while I may reach for random items to use, I’m creating a permanent piece.

works: In his book Future Shock, Alvin Toffler describes installation art as temporary. He uses the term “Kleenex art.” Keeping in mind the book was published in the ‘70s, he suggests some art at the time was influenced by our “throwaway society.” I’m wondering what your thoughts are on this.

Zoo: Well, like I said during that piece of the documentary, every space turns into a work of art. For instance, this table with a lot of stuff on top of it [a large work table in the studio] is where I work on collages. You see stamps, random paper, periodicals… Collectively it’s art. Everything in this room has order, has a place. Everything I pick up, I can’t just put it down; it has a place, an order. For instance, if I pick up this orange object and place it over here, it looks better. I’m big on shapes and the juxtaposition of those shapes. Even our clothing is an arrangement of color and shapes.

I don’t want to be negative, but maybe we do live in a “throw-away society.” Most things that get thrown away can be incorporated into something really beautiful. I couldn’t put this stuff here if it didn’t belong here [gestures]. Space is sacred. I don’t like the cleaning business! So in a sense, I do like installation art, but I think of it more like a background for theater, which I’ve also done my share of. Art is not finite. Even in music, much of it is born from a lousy childhood. I’m sure Liberace had a lousy childhood, but, my God, look what he did with it! And Little Richard, Elton John—all these artists with tremendous angst.

works: Back to the documentary for a minute. During the scene I previously referred to, you seemed quite emotional. And then your demeanor seemed to transition into a state of bliss after the arrangement of objects. Almost like a state of freedom. In a sense, Buddhist-like, meaning existence is a constant state of flux. Am I reading too much into this?

Zoo: I mean, Buddhism to some extent is where I’m coming from in the first place. I mean, all I’m doing is leveling out. You can ground yourself by going barefoot and walking around with your feet in the dirt. I’ve always done that. I’ll dig a hole outdoors and actually get in it. I take it to the next extreme. I immerse myself in the hole. I have a hole in the backyard and if no one is looking, I’ll take everything off and get myself in the hole. I’m lucky I can do that where I live. People get so freaked out about nudity today.

works: You are very well known in the Portland [Maine] art world. At the same time you’re well known for your support and counseling of those in recovery for drug and alcohol addiction. On a personal level, does art play a role in the recovery process?

Zoo: It’s all about trying to help people move forward. If I see a human being in a ditch, I’m going to jump in the ditch and the person is going to ask, “What are you doing in this ditch with me?”

My response is, “I’ve been here and I know how to get out. And I’m going to help you get out. All you have to do is listen to me.” If they don’t listen to me, they may die. I know how to help. I try to get people to get the other part of their brain working. I tell them, “Use your right brain and stick to a painting you’re working on. Don’t listen to someone saying you should be painting a particular object, like a bridge for example. Just keep painting and using your brain. Become more awake and aware of this incredible existence.”

It doesn’t matter what type of art it is. It could be playing the violin. I know a schizophrenic boy who just got a Lego set of the Titanic. He put the whole thing together in a very short time. It’s an amazing, complicated ordeal to assemble this thing. His dad just sent me pictures of it and I thought, this kid could become really violent, but instead, he made a lego Titanic. That’s important.

works: You often carry your art supplies around in a sack or backpack. Again referencing the documentary, the viewer sees you in several scenes walking through town or going into a meeting with a pack of art supplies on your shoulder. Because this is so connected to your creativity, does this bring an inner peace to you personally? Is it your “medicine”?

Zoo: If I’m going to the Motor Vehicle Department and know I’m going to be there for an hour, I’ll bring a handful of colored pencils and a board and get to work. Often people will approach me and ask what I am doing. Even doodling is creative. What I’m doing is refining a doodle into a piece of art [pointing to a piece on the wall]. I’ve done quite a few really great pieces that way, but we’re talking maybe one piece out of a hundred.

works: Would you consider that piece a “super-refined” doodle?

Zoo: Yes, I’ve taken it to a much higher level. I will say it takes an enormous amount of practice. So many people attempt to be creative then give up. There is a lot of self-doubt out here. This is America. We are a very neurotic nation. We slaughtered three million Vietnamese during the war. Yet you go there to visit now and they welcome us with open arms.

works: You’ve survived child abuse, alcoholism and cancer—and more recently, the rough end of a relationship. Did creative outlets help with your mental rebound?

Zoo: If you create during any personal turmoil, you’re going to heal much faster. The creative process heals. If you suffer the death of someone close, and put down your brush or hang up your guitar, you will sink into oblivion. You’re going to embrace negativity. Creating helps you embrace the present. When you feel deep grief over loss, it is challenging, but can be a good time to learn and create. You’re going to become a better person. The other side of it is nasty. It can be disastrous. Let things go and don’t be impatient. We are an impatient society.

works: You employ one more medium that I find fascinating. Can you tell us about your truck and the motivation behind turning that into an artistic outlet?

Zoo: I mentioned earlier that when I was ten, I got a brand new bike. It was a beautiful red and lots of chrome. Eventually everything I own gets painted—it gets “art” on it. The truck was a beautiful silver Toyota Tacoma. I knew I wanted to paint it, but maybe not to this extent. I had to make a “Fudgesicle breakthrough.” I began working on one area and it began to bleed into another area of the truck. It was challenging to start because it was beautiful and in pristine condition. But I knew I could make something better from it if I just got the nerve. I had to jump off a cliff. I started by covering the tailgate with bumper stickers, throwing paint on it, then it ended up covering the truck. I wasn’t trying to create a spectacle. I was just doing what came natural. Like I said, I paint everything I own. Nothing is safe. In a sense, the truck turned into a celebration of life. I could be in Cape Cod and a cop will approach me to ask about it. People take pictures of it. If I drive to Boston, people will stick their phones out the window to snap a picture. They’re waving, making the peace sign. It’s sending such good vibrations through the world. I’m tickled at how it turned out.

works: Is it finished?

Zoo: I still add things, but I’ll say yes. I’d hate to see it in a junkyard. I’d love to see it on Edith Wharton’s estate, but I’m a creator, not a good promoter. ∆

For more, see Working with Rainbows: The Art of Zoo Cain on Vimeo

About the Author

Richard Hunt spent much of his 40-year career in corporate management cultivating farm-to-table concepts with chefs in the restaurant industry. Now retired, Hunt resides in an off-grid log cabin in the mountains of Maine. He's embarking on a new direction and taking his passion for collecting fine art and connecting with nonconformists along for the ride.

SUBSCRIBE NOW

TO OUR MONTHLY NEWSLETTER

Share Your Comments and Reflections on this Conversation:

On Dec 6, 2022 Mark Gendreau wrote:

Love you Cousin, you bring tears to my old eyes. We are finally free.On Nov 14, 2022 Robert Grady wrote:

Rick, you have a great talent that I didn't know about. Great interview. Sounds like a dedicated man and you have captured him well.On Nov 4, 2022 Beth Sorenson wrote:

" . . .no matter what the issue is, I see the silver lining and the rainbow — always!" -Zoo Cain. Love ❤️ that & will remember it whenever I think of Zoo, who is a living rainbow! 🌈 - Colorful, tranquil, peaceful, bringing hope to many by being a power of example with a promising message of better times ahead; a new beginning after a traumatic childhood into a beautiful creative light 💡 that leads the way; a warrior of life that has brushed the face of death 💀, continuing to strengthen with each stroke 🎨; a human Angel 😇 on earth 🌎 with a personal path to the spiritual ☸️ 🌲 🕉 🌳 world; the calm 🌈after the storm ⛈! What an amazing artist 👨🎨 and soul 😇! Luv 💜 you Zoo! ✌️On Oct 31, 2022 Alex wrote:

Zoo’s Art definitely comes “with the help of God”. He is so pure, so clear in his creating, it simply pours out of him. I was lucky enough to live with beauty - him and his art - for many years. Hallelujah to you always Zooman. BTW—that is a Gorgeous piece at the top of the story!!On Oct 29, 2022 Kristin Pedemonti wrote:

A beautiful reminder to allow ourselves to break away from fear and dive in with vibrant gusto. Thank you once again for exactly the interview I needed at this particular time in my own journey. Big Hugs to Zoo, what a fabulous colorful human being!On Oct 28, 2022 John Simpson wrote:

What a wonderful story. I can only imagine how a few days with Zoo Cain would clear out some of the cobwebs of creativity and allow for more joyous activity. I will have to consider how I incorporate more of what is in this article.On Oct 27, 2022 Sarah Coupe wrote:

Beautiful snapshot of the long loving legacy of Zoo Cain. As a newcomer in AA, he was always friendly, kind and interested in what people said. He is always creating and always supporting. Such a powerful, patient, humble man. Thank you Zoo!On Oct 27, 2022 SunnyDaze wrote:

My son became an artist in prison won awards in local art shows. Beautiful creative stuff. Welded artworks his specialty. I'd sell them and send him the $$$. He flourished w/creativity inside. Outside the drugs took him up again and died of an OD. His welded squid and shark, lamp made of everything sustains me as he is in those pieces. Art saves souls. I wish it could save mine. I cant get it together, putz a little here or there and a smile forms. This interview may kickstart me into something. Thank you, dear man.On Oct 27, 2022 sadhana wrote:

Extraordinary artist and human being, one with NATURE ,a rare quality these days.On Oct 27, 2022 Christine wrote:

OMG! WTF! I relate to every word every nuance every creative vibration Zoo shares. Word UP=World UP! Dude! I wuv YOU.On Sep 7, 2022 Tad Woolsey wrote:

Well said Cliff! Nothing gets by Zoo. One of the most perceptive, gentle, welcoming, and real people I have ever met. Has helped me a lot, and I believe, I him. I love his art and his passion for it. "Nothing gets by Zoo" is a great way to put him into perspective. Great article and great read. Great guy!!! His mother must have been quite a human being...On Sep 4, 2022 Cliff Gallant wrote:

Zoo is a longtime friend of mine and has been the source of much comfort and inspiration. Along with a lot of more practical, everyday advice about how to navigate this life, Zoo also gave me the gift of artistic inspiration. Nothing gets by Zoo, and he imparts that simple wonder at the miracle of creation to everyone he comes into contact with.