Interviewsand Articles

A Conversation with Nancy Servis: The Higher Third

by R. Whittaker, Sep 9, 2022

In the fall of 2012, Berkeley Art Center director Suzanne Tan and I co-curated an exhibit of ceramic art as part of the art center’s Local Treasures program. Works by Clayton Bailey, Viola Frey, Ted Fullwood, Jon Gariepy, Mary Law, Annabeth Rosen, Nancy Selvin, Sandy Simon, John Toki and Wanxin Zhang were featured. It was a surprising event for a community art center, given its scope. Nancy Servis’ essay for the show’s catalog provided the finishing touch. All in all, it was an example—as Servis understands so well—of how an exhibit at a smaller venue can be every bit as rewarding as what can be found at the larger galleries and museums. Minus heavy media coverage and overflowing crowds one might ask, did it count? It’s a question worth pondering. Surely the standard of measure for these things cannot be simply a matter of numbers.

Servis is a scholar; has extensive experience as a curator, teacher and gallery director; and is a historian, writer and self-described storyteller. The story she shares here gives us a glimpse into all of these parts of her life, not least of which includes a lot of persistence that traces the promptings of her heart. That our conversation begins with a reference to John Toki could not be more fitting.—Richard Whittaker

works: I visited John Toki a few days and he said you had a lot to do with things at NCECA [National Council on Education for the Ceramic Arts] in Davis [CA] and he gave you very high marks.

Nancy Servis: That’s great. He’s very generous with his compliments.

works: Yes. And he recognizes the work. To start with, let me ask if there’s anything in particular you want to talk about?

Nancy: Well, I don’t know if you’re aware of the book that I’m writing?

works: I am. So why don’t you describe that?

Nancy: Okay. I’ve been living the life of a researcher and a person in the ceramic arts of Northern California for a long time. I was a curator for many years and a professor at CCA. I taught a course there called the History of Northern California Ceramics. It covered 100 years, basically, of Northern California ceramics. When I was starting to research… But let me back up just a little. When I lived in Davis, I curated many shows at the Pence Gallery. I was director there for ten years and, anyway, there were so many holes in the scholarship of ceramic history…

works: Can I interrupt? Would you say more about the Pence Gallery?

Nancy: The Pence Gallery is a small, nonprofit art gallery in Davis. It’s called Pence because it used to be the office of a dentist named Joe Pence. He donated it to the city to be used as an art gallery. For 25 or 30 years, it was very small. I became the director there in 1994, and that’s how I met John Toki. I curated a show of his work and then did a show of the Toki family’s collection.

works: How many of the legendary clay artists from UC Davis were around then, and did they appear in the Pence Gallery?

Nancy: Yes, they did. I didn’t know Robert Arneson, but he certainly knew the Pence Gallery. There was a loose affiliation with UC Davis, and there were people from the Design Department who were also connected to the gallery. The crowning effort of my tenure there was doing that whole new building. Pence Gallery now is a beautiful state-of-the-art gallery, which was really what I aimed for the day I stepped into the role of director. When I was going through the artist files to see what artists I would want to show, John’s file stood out. So, although my specialty was not in ceramics in those days, it quickly developed into that since I was seeing so much of it. I’d moved to California from New York, where I was finishing up my graduate work.

works: And where was that?

Nancy: Well, I did two degrees, one in Museum Studies from NYU, and then I did an Art History master’s degree from City University of New York. I’d almost completed my MA, but still had to finish my thesis in California. That was a very interesting process, because I moved from New York to Benicia and also became a mother. I’d often walk by Robert Arneson’s home and studio with my infant son. We lived in Benicia for about two-and-a-half years and then, because of the Loma Prieta earthquake, we moved to Davis.

I was very well-trained in the arts and museums because I lived close to New York City and did all my training there. I was a Hilla Rebay Curatorial Fellow at the Guggenheim Museum, which was really transformative. That was a great experience, working at a very big museum. I worked on select, noteworthy shows and in my research of Hilla Rebay, I found we shared the same birthday. There were all these parallels, which were inspiring because I felt like I was quite a pioneer, leaving my home in Ohio where I grew up, getting married and moving to New Haven for four or five years, where my husband went to medical school, and then moving to New York.

works: Yale, I take it.

Nancy: Yes. And I worked at the Yale Center for British Art and was really inspired by how museums can create a transformative experience. The Yale Center for British Art was designed by Louis Kahn. It had all these great functionalities, as well as being just an exquisite building. Duncan Robinson was the director there. He was a lovely man. Of course, there were many small museums and galleries in New England that we would visit all the time. I was getting ready to go to graduate school and I just loved the fact that the smaller museums and galleries could be as rewarding an experience, but in a different way, than the larger ones.

works: That’s a nice point, that smaller, less-known galleries and museums can be as rewarding as high-end ones.

Nancy: Right. It’s true because it was very impactful on me as a museologist and art historian. We visited a lot of these places. I remember seeing a beautiful John Marin watercolor painting, just this beautiful jewel. I was right there looking at it. It was very exciting—and all these experiences were memorable. Another profound one was at the Yale Center for British Art when I would go into the works on paper library and look up, say, a Turner. I could request to see an original, and they would bring it out to you. Those experiences—this is what art’s about. This is the synergy, the dynamism, the spark that most people never get a chance to have, or don’t put themselves in the position to figure out—or even go to smaller museums. So small museums can be pretty great, and they don’t cost a lot either. The Yale experience was building momentum for me. Anyway, that was the origin of Pence Gallery’s evolution, because I was…

works: You brought all that to it.

Nancy: Yes, I did. And a lot of people don’t know that—they don’t know the vision that went into remodeling that small building and making that change. It was because I had been to these smaller venues in smaller towns in the east that could provide an accessible experience. So that has worked very successfully for Pence Gallery. It’s a beautiful, small space and very appropriate for Davis.

works: So how did you get interested in ceramics?

Nancy: Well, because of the clay conference in Davis every year, I was curating shows of work by artists who were using clay. And because I was not under the pressure and influence of a Davis tradition, since I was coming from a different background, it showed in my interests and vision. I didn’t want to follow the trajectories solely of funk art or abstract expressionism.

I wanted to find new things—things that weren’t just blindly accepted.

I think that was one of the reasons I liked John Toki’s work so much. It was not Arneson- or Voulkos-related. It was John Toki. And he was one of the first people I curated a one-person show for .

works: So what was it about an artist’s work that made you think it was worth showing? How did that work for you?

Nancy: I think that’s where good curation plays a role. I grew up in Ohio and my father was an artist, among many things. Periodically he took me to the Cleveland Museum of Art when I was a little girl. So that was something, Richard, that was part of who I was—and developed into further. I would say that living in New Haven was wonderful, but then moving to New York was the pinnacle for me. I was a graduate student in Manhattan, and we had classes that were held at the Met. I had many friends who were working at museums, and we would get tickets to see shows before they were open to the public. You could go to a great show every day of the week, and these wouldn’t necessarily be at a museum. IBM had a great gallery, where you could see amazing shows. So, between my own innate skill and all of the time I spent looking, looking, looking… I just think I had a very sensitive and hungry eye.

I also like it when artists can offer something beyond themselves. That’s always a delicate area, but I saw that in John’s work. I thought, Wow, he’s really trying to go beyond the pedestal piece, right? That’s a little bit of a trap, you know. Can I make something that works for a pedestal? And John was doing it on his own. Obviously, he’d worked with Stephen De Staebler. I think there was a lot of synergy between the two, but I loved a lot of the risk-taking he did in terms of how he approached his work. I wrote an article on him for Ceramics Monthly, maybe in ’94. I was really happy to get to know him, and we’ve done several projects together.

I used to go to Leslie Ceramics and see all this artwork on display in there and I’d say, “John, what’s going on here? Why are all these works here?” So that’s how we started that dialogue on the Toki Collection. I wrote that catalog, and did a show. But my master’s degree is in 20th-century modernist painting. That was my thesis because I was wrapping up my graduate work in New York. It resonated with me and many of the modernist painters lived in that area.

works: So as a curator, you’re alert to what’s happening inside when you’re looking at a work of art—maybe something starts to resonate. Like, this is how I approach material for the magazine. It’s like there’s another intelligence. But I don’t want to put words in your mouth. How does that sound to you?

Nancy: I think that there is an intuitive response; there’s something that gets my attention. Hans Hofmann, the abstract expressionist painter, who I wrote my undergraduate thesis on, talked about this quality called “the higher third.” Have you ever read his book, Search for the Real?

works: No, I haven’t.

Nancy: I did my undergraduate thesis in Ohio on him. That’s where, I don’t want to say embrace, but I like that idea that there’s more to art—whether it’s sculpture or even a vessel. I saw a vessel by Jim Melchert and wryly said to John [Toki], “Well, if you can apply divine inspiration to a vessel, I think it’s there.”

So, Hans Hofmann talked about this higher third and how there are all these ingredients that go into making a painting. It creates something that isn’t as physically tangible. I do feel that’s forgotten by a lot of people today, and I think it still exists. But that is the beginning of the curatorial process.

One of the things I’ve always worked very hard at is selecting works, because if it’s done well, that whole higher third experience takes place curatorially, also.

works: Can you just briefly give a little more of a description of Hans Hofmann’s meaning there?

Nancy: Usually you see it when someone is awestruck, or they’re walking through a gallery with a smile on their face, or they just come back enlivened or excited. I would go to artists’ studios and look at the work—“This would be great and this, maybe not that.” Then the other thing I’d do is ask the artist, “Is there something I haven’t included that’s really important to you?” A good curator takes into consideration so many things. And it’s not just how does one work relate to another. Its also is what is the message you want that work to carry.

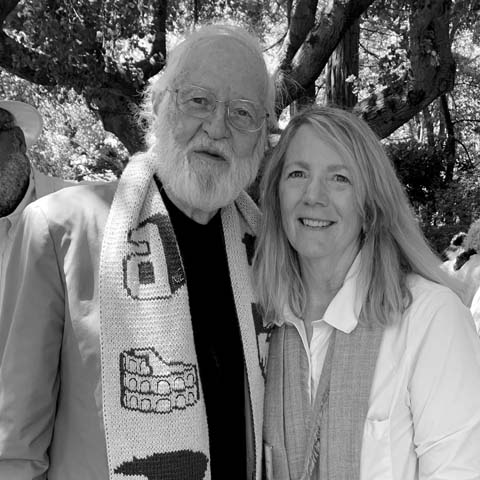

Jim Melchert/Nancy Servis

works: Okay. When you were talking about a vessel Jim Melchert made, you used the phrase “divine inspiration.” Now, I’ve encountered a scrupulous avoidance of any suggestion of the divine in the “official art world.” I know what you said was spontaneous, but would you say something about this question? I mean, for all of human history until very recently, you might say that art-making has been connected with something we could call the divine or sacred. So I don’t know if you’ve thought about that, but that phrase just leaped out at me.

Nancy: Well, I think it’s a tricky phrase, and I said it only to John Toki. I didn’t write it anywhere. I don’t think there’s any one artist, except for maybe Michelangelo, who’s embodying divine inspiration. Right? I think artists are good because they work hard. That’s one of the consistent ingredients I’ve found. Sometimes, when an artist is working hard—and I can mention people who I think fit that role—sometimes there’s this higher third component that happens.

works: That’s something in the general area of what we might call “spiritual”—is this what you’re saying?

Nancy: I would say it’s intangible, you know. It’s not a product of the material of which it’s made. You can’t take it away and remove it. You can only be there.

I also think that some people just don’t get that, don’t open themselves up enough to see that. You know Richard, I’ve done a lot of looking in my lifetime, a lot of looking. So, you start to see things that are put out there and sometimes they fall really flat. Just because they’re made by somebody who’s famous doesn’t mean they’re good. This circles back to the whole mingei idea, right? The art of the common person.

works: Right. And Yanagi’s book, The Unknown Craftsman, speaks of beauty in this territory—you could say it belonged to the higher third. And there’s James Turrell’s work. He won’t say his work is spiritual, but light appears all the time as a metaphor of the sacred.

Nancy: And we can also think of Stephen De Staebler in some of those conversations.

works: I agree. And when I interviewed Turrell, he went there in careful way. People are willing to speak of certain works of art as having “magic.”

Nancy: Did you happen to see the Stephen De Staebler exhibition at the Richmond Art Center?

works: I did, and I love that you’re bringing Stephen De Staebler in here.

Nancy: Well, we used to have a lot of conversations. I would always go to his place with a list of questions I wanted to discuss, and we’d seemingly get off-track and talk about all these other things, right? Then when I looked back, I’d realize, “Oh, we did talk about those questions on my list,” but in a metaphorical conversation. Anyway, I curated that show at the Richmond Art Center.

works: I didn’t realize that.

Nancy: Yeah, I curated that show. I was talking with Peter Selz who was there, and he was just glowing. It was very exciting for me. Curators never get any acknowledgment; it’s always the artists. But he loved the show. I had this curved wall built as a context for Stephen’s work and Peter was so complimentary. I was like, “Gosh, this is just amazing!” Because you work so hard and study so hard, and you write about it.

Anyway, I think it all worked so well. Part of it was that we had like-minded people working in all aspects of the show who were sensitive to this greater realm.Do you know Anthony Pinata?

works: No, I don’t.

Nancy: He’s a very kind man who was one of our installers. Then Derek Weisberg who was Stephen’s assistant at that time, and of course, John Toki—we all worked together. It was like a curatorial higher third. Everything was beautiful. Stephen’s health was just up and down, but Stephen and Danae [Mattes] were incredibly gracious. It was in the main gallery of the Richmond Art Center, where you could get vista views of the work. I worked with Stephen on the lighting; he was very specific about his lighting.

Later, he was in his wheelchair at that time and came down to see the show. I just happened to walk into the gallery, and I said, “Stephen, how’s it been for you to have this show? Was it everything you’d hoped it would be? What do you think?”

“Well, it’s hard to say good-bye to your magnum opus,” he said, and I just about fell over. It was an unbelievably generous thing for him to say. It was a really beautiful moment.

works: He’s one of the greatest artists I know of and deserves much more recognition.

Nancy: I agree with you. You know, I’ve done a lot of research on him, and I did read his undergraduate thesis from Princeton. Wow, some of the ideas that he kept digging into sculpturally started there—because he was at the School of Divinity at Princeton. He talked about this idea of how we were broken people.

works: His work is so profound because of this portrayal of us as broken people, but still with a spark of the divine.

Nancy: We had a real connection. Getting back to curation, my intuition and my sensitivities artistically, and spatially—Stephen was the only other person I knew who had this tendency. Whenever you’d go out to eat with Stephen, he’d want a table that had the right placement in space, and I’m actually that way, too. It drives my kids crazy.

As a person in the art world, which can be kind of rough and tumble sometimes, I come back to the fact that I’m responsible for how I actually move through the art world as an educator, a writer and a gallerist. It’s important for me to communicate on all levels what I think is really meaningful. Right? That’s a burden sometimes.

works: Yes, and especially if you feel that responsibility—and it’s a blessing that you do. The gatekeepers, the curators and directors don’t always see very well, but it’s encouraging talking with you.

Nancy: Thank you. I think there are a lot of people who just don’t take the time, or they’re intimidated by the art world. When I was at the Pence, I would always say the only difference between you and me and my understanding of the art world is that I walked through the door. I made the commitment to walk through the door, and to look. I also taught Museum Studies at UC Davis for a couple of years and sometimes I talked about some exhibits as just exposure. Exposure is important, but you can do a thoughtful curation for a show in a café.

I have to ask meaningful, probing questions about exhibitions because, as a writer, I spend a lot of time researching, and that’s not a particularly lucrative area. The thoughtful artists and good writers put their work out there. They put their good work out there with the hope that it will stand, with the hope that it will contribute. That’s part of the reason I wanted to write my book. I also felt that there are too many holes, too much blindly accepted scholarship without inquiry. There’s a lot of hero worship.

works: Right.

Nancy: There are some artists who did really break boundaries and that’s not contested at all. But it’s important to shed light on some of these other artists who were never viewed like they should be. So, in the introduction to my book, I start in 1790. That’s when there’s this influx of people into California, and it wasn’t “California” then. There was a young potter who was asked to go to the various presidios to teach ceramics, to teach pottery. That potter, Mariano Tapia, is a known person at the beginning of intentional pottery use in California.

Of course, there’s a lot of writing about ceramics in California, but very little that goes further back than 1950. There’s so much more here. So I spent a good part of my research on the period from 1900 to 1945 and telling that story. I think those are very valid stories to tell, and I also feel that the diversity of expression with clay in Northern California is partly due to the diversity of our culture. I talk about how people came from all over the world to California, to this area, and brought with them their ceramic traditions. In Northern California there’s an exquisite Native basketry tradition and not so much regarding ceramics.

works: Were you able to get any sense of the life of a potter or a pottery studio from those earlier days where you could sort of taste the life of it?

Nancy: Well, there are some very early potteries—turn of the century—and California College of the Arts & Crafts is part of this. It was established first in Berkeley. People were coming to California. They were coming overland, they were coming from Asia, they were coming up through Mexico. So the development of all types of clay use is related to population growth. There was a little pottery that only lasted for about eight years called Roblin Pottery. It was in San Francisco, and then it was destroyed by the 1906 earthquake and fire. It’s a fascinating story about this woman, Linna Irelan—not Ireland, but Irelan, and another maker from a British family, Alexander Robertson. They partnered up to make a pottery, hence the name “Roblin.”

They started using local clays. Linna was married to the state geologist who was doing research on clay, and not only were they using local clays, but they were applying fauna and flora of California onto these vessels. I actually found some articles that she’d written for newspapers that no longer exist. That speaks to an awakening of pottery and ceramic use in Northern California.

The other thing that happened right at that time is the use of terra cotta pipe—sewer pipe—and the whole Gladding, McBean business, because the populations of Sacramento and San Francisco were exploding. So with all the clay, they were making sewer pipe and then went into architectural terra cotta. When you’re in Oakland and walking down Broadway, you can see all these buildings that, from their exteriors, speak to what was happening in the ceramic world. And I talk about that, too, in my book.

At the turn of the century, you’re getting buildings in Oakland using terra cotta in a gothic revival way, and then you get into the ‘30s and you see these art deco buildings like the Paramount Theater, right? with the tile mosaics and everything. So that’s all part of the history of ceramics.

works: With that little pottery that lasted only eight years, you said they put California fauna and flora on their pots. Were these in bas-relief?

Nancy: They would have lizards as part of their decoration. They’d model them in clay and attach them on the surfaces. The Oakland Museum has a few pieces. I don’t know if they’re always on display.

works: What occurs to me, Nancy, is there was life going on, which tends to get lost. What I think of is it was a life like anybody’s life with its pleasures, excitements and struggles, like “I’m going to make this lizard and attach it to this pot. Doesn’t that look great?” or “Maybe it should be smaller.” The whole drama of life was happening, and it’s all forgotten. We discount all that. We don’t think about it. We think of the past as not as good, not as interesting, as our more “advanced” life today. It’s sort of an unenlightened view, I think.

Nancy: Well, I would agree with you. So, I go from this Roblin Pottery—and there are others, too, that didn’t survive—to the 1915 Panama-Pacific International Exposition which was built in the Marina District, which was just debris from the earthquake and fire in 1906. So they extended it, and there were small potteries there. I’m working at establishing a lineage, a stepping stone of this history of ceramic use.

works: I think that’s wonderful. Where are you, in terms of seeing it in print?

Nancy: It’s taken so long and I’m hoping to finish it up this summer. One of the things I’m also hoping to do is to include images that aren’t the standard. So, I’ve been looking through archives—like the Imogen Cunningham archive. She did a lot of incredible documentation of artists in the Bay Area. And I talk about the Mills College Ceramic Guild and the people there. Antonio Prieto had the unfortunate placement of being right before Peter Voulkos. Prieto was an amazing, transformative, fine, fine potter. I mean, people say he was a potter, yes, but he was stacking his pottery if not before, at a similar time as Voulkos. But unfortunately, he died at age 54. So, there are all these stories, Richard. In a way, I feel like I should focus my book on the period from 1900 to 1950. That’s where a lot of the information doesn’t exist. I want to pull the curtain away and acknowledge those greats. Once you get to 1950, there’s so much documentation.

When Peter Voulkos died, I was teaching at CCA, and I was impacted by that. That day I was having class, and when my class showed up, I said, “Look guys, Peter Voulkos just died. He was so important to who we are in our field today, I want you to take the day off to go find some of his work and look at it.” I have a funny story of when I met Voulkos. I was with John and it’s a hilarious story for another time.

Anyway, even with 1950 on, there are holes and that’s a tall order to do, so it’s been a very sticky process, each decade holds remarkable stories.

works: Well, your work may not be over, Nancy.

Nancy: Right.

works: I was at CCA a few days ago for that good-bye event on their Oakland campus. A lot of people showed up. I went because months earlier someone had tipped me off to some wild stuff going on behind the ceramics building. And, oh my gosh, what a collection of discarded, left-behind student clay work. So I took a lot of photos. It was so interesting, because the only curation was just chance, thanks to life.

Nancy: What happened to the artwork?

works: Some of it had been set out on the lawn in front. People were invited to “adopt” a piece of art. It was a fundraiser. The pieces were priced at $150, $300 and $450. I ended up with four of them. My wife had just left for Macedonia, and she said, “Richard, don’t buy any of those things.” She knew I wouldn’t be able to resist. Now they’re in our garden out front. I ran into Arthur Gonzalez and Nathan Lynch, and had some nice moments with each of them.

I think the left-behind art was very rich because it expressed something from the whole culture of student work, that aspiration to be an artist, the search for one’s own work, the fashions about what art should look like—all this mixed up together and visible somehow in the work that was left behind. It was like anthropology, really.

Nancy: Well, it’s interesting. What gives us meaning, right? What gives us meaning? I’m glad that CCA, particularly in the Ceramics Department, that they’re finding importance about meaning, about the history. Do you know who Donna Billick is?

works: Yes. I’ve met Donna. I interviewed Donna and Diane Ullman about their Art and Science Fusion Project at UC Davis.

Nancy: Right. I was helping her get her studio ready for something. So, we were doing a lot of work cleaning and moving everything, and she said, “Nancy, I can’t really pay you, but you can take anything on my property you can find. Within reason.”

I’d been looking at something I’d passed several times during the day. It was partially buried in the ground and I said, “Donna, I’m curious about this piece in the ground.” So, I dug it out and cleaned it up. It’s this beautiful oblong form that has an architectural component to it, and it’s very uncharacteristic of her work. So, it’s kind of that same thing. I dug it out and now I have it.

works: I like the story and it certainly parallels mine. A lot that ceramic work that was left behind really does feel like a search for meaning. Do you want to enlarge on that?

Nancy: The search for meaning?

works: Yes. Through art, you might say.

Nancy: Well, I think it’s different, depending on where you’re coming from in the art world. Right? So, I’m not a maker per se. I don’t work with tangible material. If I were to describe myself very quickly, I’d say I’m a storyteller versus a historian, because although facts are very important—and I check my facts—I love the idea of this potter in 1790.

I love the fact that here’s this man who learned to make pottery in Mexico and, through the missions, came up to the Bay Area and was then told by the church to go to these other areas and teach these people pottery. I think it’s a story that brings meaning that would not otherwise be known.

So, I’d love to sell my book. But more importantly,

I want to tell this story because that’s what’s really important to me. My motivations are a little different, and that’s why I think it’s taken so long. It comes back to wanting to make that contribution as a researcher, as a scholar. I say yes, I’m an academic, I’m a scholar because I have this very refined understanding of ceramic history in Northern California. It’s attached to my work; it’s attached to my living in an area for 35 years. It’s attached to my having conversations, to going to studios, to curating exhibitions…

Just the other day, I posted on digital media a picture of me with Karen Karnes. It was from several years ago when she was having a show at the Crocker. We had a great conversation regarding the difference between knowledge and scholarship.

You know, there are so many times where I’ll read an exhibition catalog and just come away deflated, feeling they were very formulaic and not rich in terms of life texture. Many museums are stuck in an approach where they feel that, to be authoritative, high-level academia is the only way to go. I completely disagree. I think you lose life, you lose that inspiration, that higher third perhaps.

works: Yes. Listening to you, Nancy, something in me wanted to say that in the search for meaning, it can be found in the area of the higher third.

Nancy: And I don’t know if we have a choice. I did choose to become an academic in the art world; that was a choice. But the level of inquiry and curiosity—and what comes of that—is just what I do. It’s just what

I do.

works: Well, this is interesting, what you say about not knowing whether you had a choice—and whether one has a choice.

Nancy: I just know it comes down to my wanting to tell the story, wanting to tell the best story I can. It comes down to the artists who I select for my book, or the artist who I select for curation, because there’s a story. That’s what I said to John when I was standing in Leslie Ceramics looking around at all this work. I said, “John, there’s a story here.” There’s a story, and what a compelling story that has been.

I come from a family of storytellers. My grandmother used to write for the radio back in the 1940s in Pittsburgh, PA. She was certainly ahead of her time, but she was also constrained by her time. She wrote several books about young women, and an interesting fact is that she was the writing mentor to Rod Serling of the Twilight Zone, which just blows my mind.

works: Oh my goodness.

Nancy: Yeah, and she was this really lovely, sweet, kind-hearted, beautiful grandmother we called Pearl.

I think that from her openness I learned that there are stories everywhere. And you do that, too, in works & conversations. You’re finding stories everywhere, and they’re all amazing; they all have a “wow” factor.

works: Yes. And talking with you is a good example.

I didn’t know your story, and what you’ve shared, in just this short time, is so rich. ∆

SUBSCRIBE NOW

TO OUR MONTHLY NEWSLETTER

Share Your Comments and Reflections on this Conversation: