Interviewsand Articles

A Conversation with Derek Weisberg: Momentary Eternal

by , Mar 29, 2023

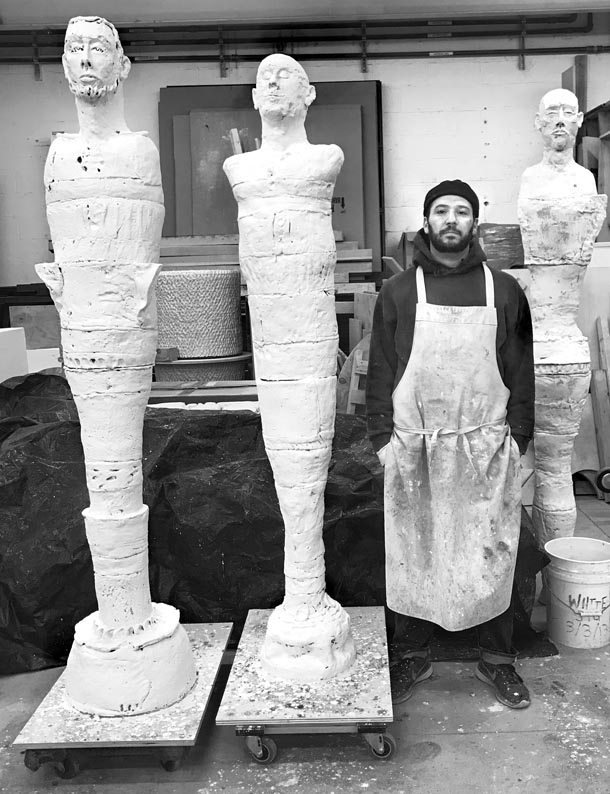

Photo. R. Whittaker

I first noticed artist Derek Weisberg via my connection with John Toki, and then further through Boontling Gallery in Oakland, a refreshing place free from aspirations to blue-chip cachet. The gallery simply overflowed with the excitement of its young artists, most still in school at nearby California College of Art. Its energy was contagious and generous, and always took me back to my own early days when the transcendent feeling of hope and confidence in a life of art was close by. And, I should add, you could walk out of the place with a piece of art full of life for under three figures.

It’s hard to explain one’s hunches, but I kept my eye on Weisberg and, over the years, was not surprised to see his work showing up in new places, evolving and finally Weisberg had moved to New York. Today, he’s a lively participant in the art scene there, both as a teacher and exhibiting artist.

On a recent visit back home to the Bay Area, I caught up with Derek at artist John Toki's studio. It seemed like a perfect time for an interview, and a couple of days later we sat down to talk.

works: What I associate so strongly with you is the figure I saw in your earlier work—the face with the forlorn expression. It was a persistent theme and signaled an alignment with the graffiti subculture, I thought. Do you think that’s accurate?

Derek Weisberg: That’s great to hear because, at that time, that was my goal.

works: Well, I’ve been impressed for a long time by how alive street art often is—a quality that’s often missing in the art one sees in the galleries.

Derek: Well it exists, you know? Public space is available for everybody to observe and take in, and also to change - if an individual wants. It has its own life that affects everybody who walks past it. And it changes over time. It’s a beautiful thing, that access, because the art world can be elitist and stuffy, and so specific. Right? You have to make a point of going to a gallery at certain hours on certain days. It’s a very focused activity. The graffiti subculture, the visual subculture - which I was really interested in at that time - is for everybody. That’s really important, I think. Maybe increasingly important in today’s world.

works: What drew you to that?

Derek: I was a kid in the 90s in the Bay Area, and I listened to rap music and did graffiti. I had friends who were break dancing and I was very involved in that.

works: How did you get involved in it?

Derek: Good question. I don’t know. I was just nine, ten years old. That’s what was on the radio - rap, hip-hop. It really started to take on a global stage in the early-90s.

works: So where were you?

Derek: Benicia. I was born in ’83 and remember listening to rap songs when I was pretty young.

works: Were kids your age in Benicia relating to this?

Derek: Listening to it, yeah. A lot of important rappers and DJs and graffiti artists have come out of the Bay Area.

works: Tell me how as a kid, say 10 years old, in Benicia - how were you connecting with that? Did you have friends into it?

Derek: Yeah. Definitely. Friends. And the radio was usually playing local rap artists or people from L.A..

works: How about the visual part?

Derek: That came a little bit later, probably towards middle school. I have a distinct memory from when I was 13. My cousin who was living in Massachusetts came to visit. He brought with him the first album by Wu-Tang Clan, a group out of New York. That kind of changed everything. Their sound was so intense, and that really set me on this course of trying to discover new sounds, new music. I’ve always really responded to music - to that energy, the vitality of it. But in terms of the visual culture and graffiti, I think that started more for me in middle school.

works: Did you have a racial mix of kids in your middle school, like did you have any friends who were black?

Derek: Yeah. My best friend since like age six or seven was Aaron Young.

works: And he was into rap and things around that?

Derek: Yeah.

works: It’s a beautiful thing when you’re a kid early on in school. You don’t have these barriers. In sixth grade I had a friend, Johnny Cortez. I loved the guy and it never crossed my mind there was any issue there.

Derek: Right. No otherness. I mean, for the most part, Benicia is pretty solidly middle, to upper-middle class and fairly white. But it’s right next to Vallejo, and there’s quite a bit of cross-over that happens.

works: So in middle school this was opening up more?

Derek: Definitely. And in the mid-90s, rap was infiltrating every corner of American life - like suburbs in Idaho.

works: That’s something, isn’t it? How this form has penetrated the whole world. I had a conversation with Mark Bullwinkle years ago about how African American culture has given mainstream culture so much, and it’s always getting appropriated.

Derek: I think it’s definitely true. Generationally, you can see that. There’s always a counter-culture, or a subculture, that people respond to - especially maybe for kids of privilege. They’re still rebellious and trying to find their way, trying to navigate through the world and push back.

works: And this was also true for you?

Derek: I mean, I wasn’t too rebellious. My parents were pretty cool. Very early on they realized that if they allowed me to make my own decisions and kind of treated me like an adult who was going to make his own responsible decisions, that I would. Basically, as long as I was getting good grades, I could go do and participate in whatever.

works: Give me just a little thumbnail of both parents…

Derek: Both born and raised in New York. Moved to California in the late 60s—hippie-progressive and kind of radical.

works: So they came out for the hippie thing. Of course, it was in New York, too, but San Francisco was the center of it.

Derek: I think they were here for the Summer of Love, and my dad went to Woodstock. They met at the Russian River. They raised llamas on kind of a co-op commune when I was born.

works: That’s great. I was at the Summer of Love and lived near the Haight Ashbury. And the feeling I get from you and your work fits in with some of the values from that time.

Derek: Yeah. And there’s always that question of nature/nurture. I think I’ve always been an old soul - kind of that cliché. I’m sure a lot of it comes from my parents’ input. But part of it has to do with a feeling of knowing what I wanted to do. I’ve had this sense of purpose from the beginning. So I didn’t need to be so rebellious. I just kept doing, kept following that.

works: How would you describe that path that you knew you wanted to follow?

Derek: Well, it’s the artistic path, the path of a maker, and I probably have always identified as an artist.

works: What is it that the artist does?

Derek: Oh, man. [laughs]

works: [laughs] I should apologize for that question.

Derek: We need to schedule a part 2, 3 and 4 for that question, I think.

works: You know what? That’s a good response. So let me jump to another question. I looked at your website and took some notes on your titles. It’s clear that you’re pretty philosophical. I think that word fits you.

Derek: Yeah, definitely.

works: You’re someone in front of deep questions.

Derek: Yeah. I think that for a very long time that’s been my kind of quest.

works: Say more about that if you can.

Derek: Well, it does go back to that question of what the artist does, or what their role and responsibility is. I think all artists are different and take on different pursuits and quests. But maybe that’s it, right? An artist is somebody who’s trying to answer questions about what it means to be living. For me, it’s really about that—what it means to be a living being, aware of our own finite nature, and how we wrestle with that.

The world is a curious place. It’s never cut and dried or black and white - even if we think it is, or have moments of being a little closer to that. There’s always nuances and subtleties, and questions that we’ll never have answers to. That’s where I’m searching. That’s where my path leads me - through that space.

works: There was a phrase in common usage when I was in college in the 60s and ended up getting a degree in philosophy: “art, philosophy, and religion.” It just rolled off the tongue. What you just said reminds me of it - that for you, art is an avenue towards the investigation of these deep, human questions - the existential questions. The word “religion” - is a loaded word today for a lot of people, but the word “spiritual” still has a little bit left in it.

Derek: Right. I think they all attempt to answer those same questions - the questions that are bigger than us.

works: When I first started publishing a magazine in 1991, the Postmodern critique had gotten rid of all the “grand narratives” around Truth and so on. They were all skewed because of issues of power and cultural relativity. An artist could be embarrassed to admit that he or she was engaging in "the search for meaning" - like such a goal wasn't sophisticated.

Derek: It’s interesting that we’ve shifted to this conversation. I think it’s something needed, and maybe the cultural pendulum is starting to swing back a bit as things have gotten too abstracted, so removed. Most people spend most of their time in front of a screen.

In New York where I teach, I see how many people are gravitating towards making things and having experience with their hands and physical material because it brings them back to the world. It’s not just this abstracted experience with a screen and a virtual reality. Another example is how much people are into food now. These things bring us back to the Earth in some way.

works: Would you go so far as to say that when you’re making things with your hands that something is being nourished in you?

Derek: Definitely. Yes, definitely.

works: It’s like some kind of needed food.

Derek: Yes. I mean, I’ve equated making things with breathing, in a lot of ways. I’ve been making things in clay since I was six or seven, so it’s just this natural extension. I can feel that my physical being is not well when I’ve gone through periods when I haven’t been making things regularly.

works: One of your pieces is titled with something to do with breath.

Derek: In the Space of a Long Breath.

works: Does that relate to what we’re talking about?

Derek: I think so. And also, that’s probably an older piece. I’ve made so much work and so many pieces have these long titles having to do with breathing. My mind’s running all over the place right now… Maybe I have to rewind a bit.

My mom passed away in 2006. She was sick for many years before that. That was such a momentous event. Being a teenager knowing that your mother seems well, but is terminally ill was certainly a challenging thing. Then to see her go through that process, and deteriorate - watching her breathe… You know, you’re watching and thinking about that space between one breath and another, knowing it could be the difference between life and death.

works: Oh my.

Derek: So that title was in direct reference to that experience. But I also think of Eric Garner, you know, “I can’t breathe.” You could say that these political and social issues that have come up, are also around the idea of breathing.

works: That is all so touching. It takes me back to my own experience of sitting at bedside with my mother when she died, and her last breath. We’re at the edge of the deepest realities here. So, I want to back up to that face I think of in connection with your work, which is iconic, in my mind.

Derek: Right.

works: It’s the face of - what would you say? I mean, it powerfully communicates a kind of unhappiness.

Derek: It’s melancholy, which I think is a much more philosophical word than just “sad.”

works: Yes. Can you talk a little bit about that face and why it was so important to you?

Derek: Yeah. So, we’ll track back to graffiti. Growing up in the Bay Area in the mid-90s, there was a whole group of artists who kind of came out of the graffiti culture and started making art on the streets. In San Francisco, and in the Bay Area at some point, it got coined the “Mission School.” Artists like Barry McGee and his late wife, Margaret Kilgallen, were painting these figurative, graffito-like murals. There were people in New York - Phil Frost and other artists - making stylized, cartoony figuration, kind of illustrative, but very expressive. Things were exaggerated - facial features were exaggerated - and it was all out on the streets.

I gravitated towards that. I mean, I kind of viewed them as my older siblings who I wanted to hang out with. I realized I was a second wave of that, and they were having conversations I wanted to be involved in. There was that shared graffiti aesthetic of existing on the street - murals for everyday people - and about everyday people, that I both responded to and wanted to express myself.

I was always making things in clay, so I wanted to translate that aesthetic into a sculptural form. The figures I was making at the time were very stylized - all the details. So that’s the connection to what I’d say was a larger aesthetic movement.

works: Okay.

Derek: The reason I probably responded to it, and thought it was important, was because I was interested in those same ideas - you know, the idea that everybody deals with similar human issues.

So, I was making this one figure that was a stand-in for everybody, kind of a universal-like figure. And dealing with my mom, dealing with whatever I was going through as a young person trying to find his way, it took on these melancholy characteristics, I guess.

works: You were feeling that yourself, this kind of melancholy?

Derek: Yeah, yeah. Definitely.

works: So the context of that was - I mean, if you care to reflect any further on it.

Derek: Certainly what was happening with my mom. And I was in my late teens, early 20s. There was heartbreak, you know, from early experiences with love and loss. And maybe also trying to fit in, find my people. I’d left my home in Benicia and moved to Oakland. I was finding new friends and trying to find my way, and that can be challenging.

works: To say the least.

Derek: And I was also under the impression and belief that you really find yourself in those darker places, that your sense of self, or character, is really defined by how you deal with the challenging things. Life isn’t always so easy or beautiful, and how you wrestle with that, and deal with that, really is more defining.

works: Do you feel lucky because you’re following a path with heart?

Derek: It is one of, if not the greatest, gift that I’ve been given in my life, definitely.

works: And sadly, it’s not so common. It seems very hard to find that here in our time.

Derek: Yes—and to be supported in it, that’s incredible. It’s really incredible. Again, we’re so removed. Right? Back to the media screen, or back to where things are produced - like who makes things with their own hands anymore? Everything is at a remove and abstracted. Even if you try to deal with an Internet problem, you have to call some number and it’s an automated thing; there’s that music, and you have to wait; then they connect you with somebody who then has to connect you to somebody else, who then puts on more music; then you finally talk with somebody in India, or another country who has no idea about your actual surroundings. It’s all so far, far removed now. And to pull it back in, I think, would be really helpful to humans.

works: It’s so hopeful that you’re giving voice to this lack of connection, and the abstraction of it all. It reminds me there’s a book that came out a few years ago, Shop Class As Soul Craft. The author’s premise is something like, “Making or fixing things with your own hands is a real support for our health - inner and outer.”

Derek: Yeah. Inner life and outer life. If you’re doing that kind of activity for yourself - not for any other reason - that’s a real act of love, I think. You know that you’re going to make this cup that’s just for you; that you’re going to drink your coffee from it every morning, sit in your favorite chair. If you are having that kind of experience, creating that act of love, then you’re going to bring that out into the world, too.

You’re going to be fulfilled. You’re going to smile at the cashier. You’re going to say “Hope you have a great day!”— just little acts of love will be carried out into the world, and those are also missing. I think it’s needed. It’s important.

works: I have to agree with that. Totally. And. let’s go back to Boontling Gallery. I loved the place. It was full of that atmosphere of young artists - the conviction that they were onto something so good and real. And you were one of its founders? [yes] So tells us about the gallery and a little about your cohort and experience with it.

Derek: It was started by me and my friend, Mike Simpson. It really came out of - I was going to say not knowing exactly what we were going to do after school, but it’s kind of the opposite. It was knowing exactly what we wanted to do after school - which was make art, continue showing art, and continue nurturing the artistic community we’d been experiencing at CCAC. But we didn’t know exactly how to do it. So we decided to do it by opening Boontling. The name comes from the town, Boonville [California], and an American dialect from that town.

A friend found a Boontling dictionary that said it was the language of the 49ers. The actual history is slightly different, but there was a group of friends from college, and we called ourselves “the 49ers.” We’d go on weekend quests through San Francisco, or walking down railroad tracks finding debris we’d use in making art, or taking photographs, or we’d paint graffiti. We’d have these weekly adventures searching for “gold.” So we were “The 49ers.”

works: Nice.

Derek: We loved that, and kind of continued it with the name and the gallery. The gallery was open on weekends. I was a delivery driver for John Toki at Leslie’s Ceramics, and I was working for artists. Those were my regular income jobs, and then we had the gallery. It really became kind of a clubhouse-community hangout. We would do things like have these shows called “Overhung.” We were trying to get rid of the stuffiness and eliteness of galleries. Anyone could be in “Overhung.” We’d hang these shows salon style, sometimes from the floor to the ceiling. There were hundreds of pieces of art. By doing that, it became a place for the art community at-large in Oakland. That was really special and allowed us to stay involved in the community, stay involved in art, and also to give back to artists and artist friends who we admired. It was fulfilling - a kind of special place and time, I think. We were 21-year-old kids who knew nothing about business or running a gallery. It was all just very DIY.

works: What a great spirit, though.

Derek: It was great. There was something to not doing too much and just going for it.

works: And it lasted how long?

Derek: About two-and-a-half, three years, I think. Then Mike moved to New York and in the middle of it, my mom passed away. So I was torn. I suppose I could have continued to do it with somebody else, but it didn’t feel right to change that spirit.

works: How did you meet John Toki?

Derek: He was one of my professors at CCAC.

works: When it was still the California College of Arts and Crafts...

Derek: …as we talk about crafts - and loving it.

works: Could you say something about John Toki?

Derek: That’s like asking what the purpose of an artist is. How do you say a few words about such an incredible human being, incredible artist and incredible teacher? I mean, he was so generous and so knowledgeable. He made a real investment in both CCAC and the students. It seemed like he was willing to give more to us, and to the institution, than he was to himself. He was completely unselfish.

works: Yes. I don’t think I’ve ever met anybody more generous than John. And I’ve heard that if a student wanted to do something that others thought was “too ambitious,” he stood behind the student all the way.

Derek: Completely. I mean, he let me live and work at his studio when I graduated from school. He carved out a little space and I was living over there in Richmond.

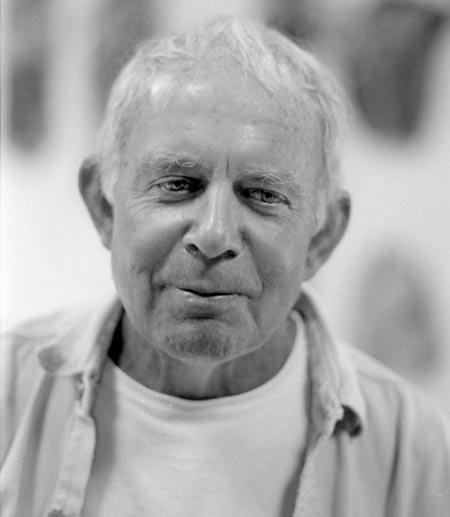

works: So that’s John. And you ended up having a deep relationship with Stephen De Staebler. Would you talk a little bit about that?

Derek: You know, that was a combination of being in the right place and time, John’s generosity, my dedication to work and school and craft and my own skills, probably - a combination of all those things.

This was around the end of 2005. I’d graduated from CCAC in May and was working at Leslie’s Ceramics. Stephen came down one day looking for someone who could help him load a kiln. John said, “I’ll send Derek up.”

So I helped him load a kiln. Then, a couple of weeks later Stephen’s wife, Danae Mattes, called me and said, “Now we need help unloading the kiln.”

It wasn’t long before Danae asked, “Could we get you to help Stephen in the studio on a more regular basis?” So I had a working relationship with Stephen as his assistant for about six years, and then he passed away. I kind of helped set up the estate before I left.

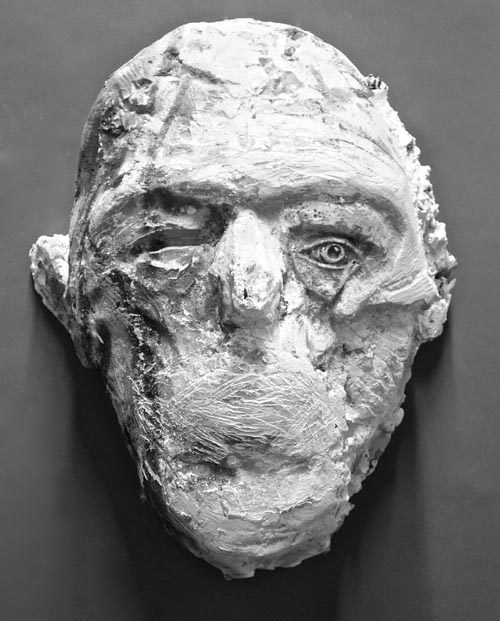

Stephen was an incredibly special person - and special artist. I mean, you knew him. He was incredibly thoughtful and an amazing man. Just getting to have a relationship with a person like that would be amazing. But it’s even more amazing because he was this legendary, kind of iconic, figure.

So I have to rewind a bit, and this ties into a lot of the things we’ve talked about. When I was 14, my parents sent me to the San Francisco Academy of Art programs they had for high-schoolers. I both needed to get out of the house in the summer and wanted to be doing some kind of artistic program. So, for one of my classes I’d get off BART and walk down Market Street, and on Market Street there’s that angel. When I saw it I thought, “Holy, shit, this is one of the most incredible pieces of art I’ve ever seen!”

I made sure that every day I walked past that angel. It wasn’t until I was in college studying art history that I learned it was Stephen De Staebler who made it. So, I had this kind of gravitational pull toward Stephen and his work from early on. Then to get to work with him so intimately - that was another one of life’s incredible gifts I was granted.

Stephen De Staebler - photo r. whittaker

works: Thanks to John, I interviewed Stephen and just fell in love with the guy. I think was one of the pre-eminent sculptors in the West.

Derek: I agree.

works: He’s certainly recognized, but not as much as he should be.

Derek: Nowhere near.

works: And I see his influence in some of your work, too.

Derek: Yeah. Huge. And I often reflect on my time with him, and his influence on me. You know, Stephen never had assistants. I mean, I think John helped him from time to time on big projects, but he never had a full-time studio assistant. He was, I think, probably just incredibly independent and also just loved making things on his own.

But for whatever reason, he and I really gelled. There were also some parallels and crossovers that we were both genuinely interested in. It was very clear we were both on the same path, even though there was an age difference of 50 years. It really worked that I was his assistant and he was my mentor. That commonality was just there from the beginning.

works: I can see that. And I love the story of your being so taken by that angel on Market Street. And then the connection later on. It’s almost one of those mystical stories.

Derek: Yeah, yeah, yeah.

works: He touched my heart. There’s a photo I took that captures something of his spirit. It’s on his Wikipedia page minus a photo credit [laughs]. And that interview is something special.

Derek: I can’t believe I haven’t read it.

works: By the way, I love your titles.

Derek: Thank you. Most of them are rap lyrics or things I’ve pulled from reading.

works: They open the door to deep areas - like Momentary Eternal. Wow, I love that phrase.

Derek: Well, I mean, it evokes in me one of life’s great pursuits - religion and the human experience, right? To be completely present in the longer, energetic lineage of what is channeled through us while we’re here, and goes on beyond us as we leave this world. It’s both, you know. We’re connected to our immediate world through the present moment, and to the ripples and repercussions of the larger world beyond us that are eternal.

works: That’s beautifully said, Derek. Here’s another title A Familiar Knowing. It’s a wonderful phrase.

Derek: Yeah. I think all of the phrases, or at least most of them, address these big ideas.

works: And your titles help. I don’t buy the claim that the author has no special access to the meaning of his or her work. Roland Barthes’ essay “The Death of the Author” had a big influence. And with the Postmodern critique, interpretation became the realm of experts - students of Derrida, Foucault, Lacan and so on. I find it refreshing to hear you say that maybe the pendulum is swinging back - not that they didn’t make some good points.

Derek: Yes. I think the things that get created, that have real impact, are the things the world needs in that moment. So in a way, probably we needed to go there. I mean, I hope the pendulum is swinging back.

I think it is, and at the present moment, I think it’s actually what’s needed. Whether art work that addresses those issues gets credit now or not doesn’t matter, but I hope that when we zoom out a bit that we’ll see the artists addressing these issues will reflect what is important at this time. The “isms” don’t really exist anymore with computers and the Internet. I think some kind of spiritualism is what we need.

works: Yes. Now am I right in thinking you had some connection with Ursula von Rydingsvard?

Derek: We were together for a couple of weeks at Cheryl Haines’ place up near Nevada City [California]. Ursula was invited to do a short-term residency, and she wanted to work in clay. They hired me to be her assistant.

works: How was that?

Derek: That was interesting. She’s an intense woman, and I learned some things from her. I mean, a woman making sculpture in New York in the 70s, 80s - you had to be an intense person to survive.

So, she came with that intensity and was ready to make some things in clay with a “professional” - someone who knew what they were doing. And here I was, a twenty-something-year-old.

She said, “I was not expecting to work with some kid right out of school.”

I said, “I may be young, but I know some things.”

So the first day was spent walking around the property. “What if I wrap clay around a rock or what if I wrap clay…”

“Well, you could do that, but this is what could happen.”

So, the first couple of days was spent making pinch pots, and I was almost falling asleep standing up. I was excited about her being there and it took a few more days for her to get a sense of the material and think about what she wanted to make.

But she ran a tight ship. So, one morning we were in the studio at eight. She shows me a drawing. “Okay. I want to make this six-foot tall piece. It’s going to look like this.”

I thought, “Great! Like finally, we’re getting into it!” So, I pull out the clay, open the bag and start cutting it up. I start getting it set up for her, and she had an “ah-ha” moment. “This kid is the real deal. He does know what he’s doing!” And from that point on, we had a fantastic working experience.

It was great. We were both like engines roaring, just gung-ho all the time. We really had a great time making this work together. It took a bit of ironing out the wrinkles, but we got there. In the last several days of working together, we made three or four really large-scale works.

works: That’s a great story. You know, I interviewed Ursula. It’s a good interview, but I felt there was much more there that I couldn’t get to. She’s one of my favorite sculptors.

Derek: She’s incredible. The way she transforms the material into something completely otherworldly. It’s her language, and so unique. She’s not like anyone else.

works: Indeed. Now, getting back to your titles, here’s one: Ontological Splendor. What do you want to say about that?

Derek: The beauty of being. Of creation. That idea of being, of self, and of place.

works: You know, I had a smirk on my face when I asked that - which I need to apologize for. I wondered if you were making light, and you’re not.

Derek: No, and I totally have to admit that I’m not deeply knowledgeable about the idea of ontology.

works: It's interesting because "being” is a word we have no associations with other than Shakespeare’s “To be or not to be.” But that’s like a cartoon version of the reality of being.

Derek: Right. Well, how do you give definition to a living being, a living creature in space, time - in an environment? I mean, that’s everything, you know?

works: Yes. And if we’re in a space of being, that is, if I’m actually present, that’s an incomparable thing.

Derek: That also gets back to how challenging it is. Because to be in that state of being means you have to be present with yourself - which means you have to be honest with the entirety of yourself, and your actions. And how you move through the world knowing that you’re going to die. That’s scary for a lot of people.

works: No kidding.

Derek: So we do everything we can to avoid that. I’m not thinking about death. I’ll distract myself, and all those distractions mean, again, you’re not being present.

works: Right, right.

Derek: So how do you…? I mean, it’s a complicated thing. But again, going back to that root of art, religion, spirituality, philosophy…

works: Right. Do you find, in making a piece, there are moments where you feel you can say I am? Not as a thought, but an experience: I am here. I exist.

Derek: When I’m in my best place. It’s hard. I mean, I am both in my best place in this studio, and when I’m in my best place is when I probably make the best work. It’s also when I’m the most fulfilled, and you don’t get there every day. There are an awful lot of distractions. But when I’m really in it, it’s a great thing.

works: More real, wouldn’t you say?

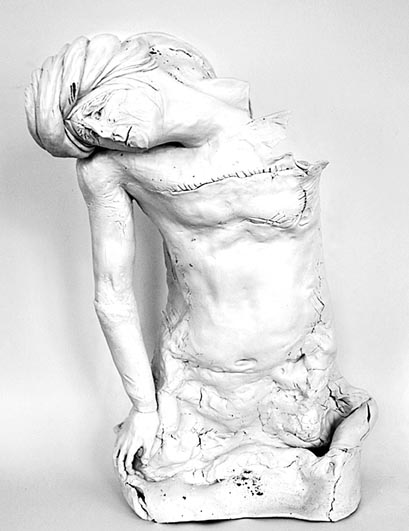

Derek: Yeah. And I think - to come back to those sad-eyed, melancholic figures - I’m realizing that they were this formulaic thing. Now, when I’m in the studio, I do everything I can to get away from formulas, from routines - to get away from the predictable or prescribed things. It’s all an attempt to make something in that present moment.

There’s a sense of living in this object that I make - the marks, the fingerprints, the way the clay is joined together; those things are left to show and express that sense of creation and being and presence. It’s all more or less - what’s the word?

works: The evidence?

Derek: The evidence. Exactly. That’s the word. ∆

For much more visit Weisberg’s website:

https://derekweisberg.com/

About the Author

Richard Whittaker is the founding editor of works & conversations and West Coast editor of Parabola magazine.

SUBSCRIBE NOW

TO OUR MONTHLY NEWSLETTER

Share Your Comments and Reflections on this Conversation:

On May 12, 2024 Kristin Pedemonti wrote:

Thank you Richard for bringing Derek to us. What a beautiful soul. I needed the reminder to continue to follow one's heart & not get caught up in finances or societal pressures . Hearing the mystical connection of Derek to Stephen was also heartening. I resonate so much with the notion of lineage and what is bring channeled through us & left behind by us too.