Interviewsand Articles

WAYMAKING WITH BILL YAKE

by James Manteith, May 5, 2023

Left - James Manteith

Oakland-Arroyo Seco, California, March-April 2023

Bill Yake was a poet* whose inner treasure revealed itself splendidly along trails. Although I first met Bill in Port Townsend, Washington, at the Centrum Writers Conference in the summer of 1993, we became better acquainted there a year later when he and his close friend Greg Darms invited me to tag along with them and another outdoors-steeped poet, Douglas Jeffrey, on an outing to the summit of Mount Townsend. Still in early stages of discovering poetry, I was sixteen going on seventeen, with these poets some thirty years my senior. At Centrum, they and many other writers showed incredible graciousness in treating me equitably, even though I was far from their equal. A native of nearby Port Angeles, I’d grown up hiking in the Olympic Mountains but had much to learn from an expedition with such poets, informed by creative sensibilities, literary scholarship and scientific training.

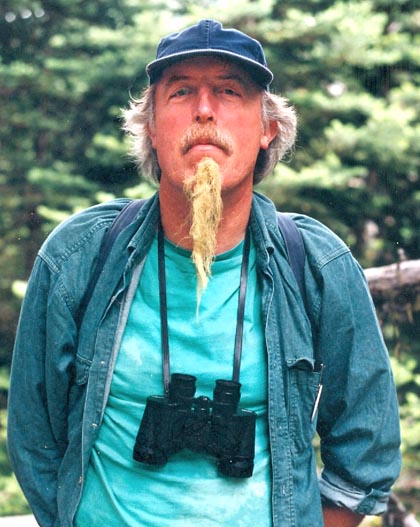

In homage to the Chinese sages, at some point we all used tree sap to stick Spanish moss to our chins. Douglas, who worked as a San Quentin Prison librarian, kept his wilderness practice more subdued and introspective, while both Greg and Bill slipped effusively into Lao Tzu and Hanshan character, with Bill’s imposing stature and slight stoop enhancing his deferential bows, hands folded in prayer. Indeed, Bill’s stoop made him seem predisposed to bowing, as if bashfully wishing to make himself less conspicuous—an impression complemented by his soft-spokenness. Perhaps in adolescence he had sprouted upward quickly, then never quite adjusted to a height made suddenly his own. His build, though, gave him a long hiking stride and possibly even an edge in basketball, a sport he’d dabbled in, overcoming his gentle bemusedness.

As was Greg’s and Douglas’s, Bill’s authentic sagacity was capable of diverse manifestations: besides expertise in animal tracks, for instance, Bill had a savvy eye for scat. At one point along the Mount Townsend trail he crouched down and with his bare hands delightedly dissected an owl pellet. The mouse skeleton he unearthed inside remained as a mosaic to decorate the trailside.

Douglas may have walked most conscientiously. Greg’s perambulations reminded me of Peter Pan. And Bill loomed like a totem pole uniting us all as we surveyed the vegetation, scouted for critters—as Bill liked to call them—and listened to birdcalls.

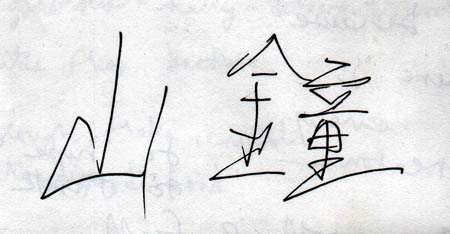

The views from Port Townsend’s patron summit were glorious. We perched for a while there on boulders, where the seasoned poets jotted in their notebooks—Greg’s including renderings of Chinese characters he liked to probe for inspiration.

Among Bill’s many critter familiars, owls had a central place in his heart and poetry. He sometimes assumed the alias "Spedis Owl," a name associated with a petroglyph motif found along the Columbia River between Washington and Oregon. The symbol fit him—a large bird who seemed drowsy, but in fact was poised to pounce with precision of act and word.

For the summer of my initiation at Centrum—an arts organization housed at decommissioned Fort Worden—the director had declined review of my fifteen-year-old self’s writing as a basis for full admittance. Instead I was allowed to audit thanks to testimony and promised chaperoning from my mom Robbie, a journalism professor and aspiring memoirist. While I focused on poetry, she took prose classes with Northwest writer David Guterson, soon to publish his first novel, Snow Falling on Cedars. This summer was also William Stafford’s last. The Oregonian poet and pacifist passed away about a month afterward. Stafford had a warm, humble presence, kind but firm, quietly subversive, but excitable. Bill and Greg loved Stafford, and each carried some of his qualities.

I had my first contact with Bill and Greg in workshops led by Stafford’s younger friend and collaborator Marvin Bell. Both Centrum fixtures, they dialogued through poetry (see their collection Segues) and would leave each other poems on a bulletin board all could read when passing through the hallway of the old clapboard building that housed our workshops. Bell and his students met around a ring of tables in a second-floor classroom, with a view out over Fort Worden’s grounds.

At first I had to sit separately, but Bell soon invited me in with the rest. This move was met with complaints from some of the full-enrollment students, and I was obliged to recede again. The next morning, the bulletin board featured a bitter poem by Bell: “Poet A writes at the seminar table. Poet B has to stay at the back of the room…” An open-enrollment instructor, Christianne Balk, said that even as a high-schooler I could study in her upcoming University of Washington poetry class, a distance-learning course for all ages. Meanwhile, more charitably-minded Centrum students like Bill and Greg looked after me for the conference’s duration.

Bell took the next year off from Centrum, and the 1994 writers conference introduced me to many new faces. Now past my probationary summer, I was fully enrolled at Centrum and on my own. I studied with the Buddhist poet Jane Hirshfield while Bill and Greg took workshops from eco-poet Pattiann Rogers and formed a deep friendship with the nature writer Robert Michael Pyle.

That summer, a bond arose among poets Bill, Greg, Nancy Cherry, Devon Vose and, blessedly, me — the Fabulous Five. Rooming in one of the barracks, in the evenings we chatted and swapped poems, relishing each others’ approaches: Bill’s mapping a cosmology of conservationism, Greg’s experimenting with phenomenology, Nancy’s capturing the fragility of life and nature, Devon’s diaristic and winsome and mine still casting around.

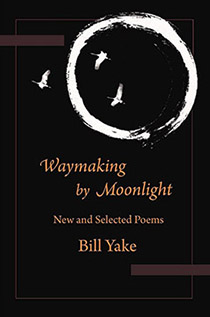

On one of our last nights together, we went out late with wine and flashlights, following a path to the fort’s abandoned bunkers defending Puget Sound. In a highly convincing manner Bill howled at the moon. Later, fortified by our collective spirit, I wound up walking back with Bill. As we made our way through the trees, he illuminated the path. At one point, he held back a branch and, as I passed through, chuckled mysteriously, his flashlight at his chin making his face a mask of light and shadow. Many years later, when I learned that Bill had chosen the title Waymaking by Moonlight for an anthology of his poetry, I remembered our passage that night—and his eerie visage etched in eternity.

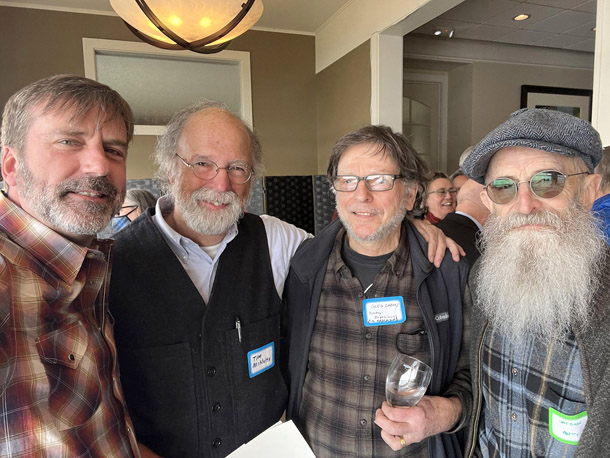

[ Pictured left to right: Northwest poets Derek Sheffield, Tim McNulty, Greg Darms and Joseph Green ]

Between my graduation from high school and my first year of college, I had a chance to get to know Bill more fully when he drove Devon and me in his Isuzu Trooper from Washington to California to attend the “Art of the Wild” writers’ conference at Squaw Valley. On the eve of our departure, Devon and I spent the night at Bill’s old farmhouse on the outskirts of rural Tenino. He lived an unadorned, solitary life there with a thoughtful collection of books and records. When I expressed curiosity about "Morrison Hotel," Bill put it on the turntable, and the Doors’ “Roadhouse Blues” became an anthem for our voyage.

Before heading south, we accompanied Bill toward Olympia and his day job at Washington State’s Department of Ecology to drop off a report on fish and dioxins before shifting into poetic mode for the weeks ahead. Traveling with Bill, Devon and I soon discovered he was as much at home on the road as he was in his old farmhouse. His poetic consciousness seemed to abide in his vehicle and to fan out into whatever landscape he navigated. He sometimes played music cassettes or poets reading. A crate in the back of the Trooper held a selection of books that included Lew Welch’s Ring of Bone and a worn copy of Gary Snyder’s Six Sections from Mountains and Rivers Without End. Bill loved that Mountains and Rivers commemorated U.S. 99, the antique, north-south highway that passed through Olympia and Tenino. The spirit of Snyder’s poems and writings still flickered in the forests and grasslands we were passing through.

That first night, we stayed at a budget motel in the southern Oregon town of Lakeview. We breakfasted on cereal doused in reconstituted powdered milk—a recipe from Bill’s college days, when he’d deemed austerity a key to life as a poet. His metal road-bowl was of similar vintage. By then he could laugh about such utopian strictures, but vestiges remained as characteristics of the muse he communed with, melding poetry and scientific discipline.

On that drive we learned, as well, of a sacrifice he’d made early in his life, giving a child up for adoption. Full of regret, he contemplated whether he might find his son, whether his son would welcome their reunion, whether their lives could accommodate each other.

A series of towns became triggers, in the parlance of Richard Hugo’s The Triggering Town, which Bill read aloud from. After a long, barren stretch of Nevada desert, when Highway 395 finally brought us to Hallelujah Junction and its centerpiece—a dismal, corrugated-steel-sided convenience store—the three of us exclaimed, “Hallelujah” with all due sincerity.

Goals were not the most important part of traveling with Bill. What mattered more was the journey and all he brought to the endeavor. He covered ground quickly, but mindfully, and was always ready to pull off to take notes on flora and fauna in his miniscule handwriting. And there was live music. He played his guitar to selections from Alan Lomax’s The Folk Songs of North America. I’d brought my guitar along, too, and on a sunny lunch break along the Truckee River, he introduced me to a Lomax gem, “Every time I go to town, the boys keep kickin’ my dog around,” which became a merry duet.

At Art of the Wild, the Fabulous Five shared a cabin, Greg and Nancy having joined us. Gary Snyder, one of the conference’s founders, taught and read there that year. His burning of sagebrush to purify the directions formed a perfect counterpoint to the poetry he offered, just a year away from the completion of his Mountains and Rivers epic.

We studied with Pattiann Rogers and Jane Hirshfield again, as well as with Brenda Hillman, then at work on her alchemical poems in Loose Sugar. Hirshfield’s new essay, “Writing and the Threshold Life,” stunned us all. Its invocation of Victor Turner’s notion of “the liminal” to describe the role of poets shaped how I saw our destinies.

Afterwards, on the road back to Washington, Bill seemed revitalized and confident, and ready to explore new ideas. At Powell’s Books in Portland on the way down, he’d picked up The Yale Gertrude Stein and, on our return trip, he read from this volume, rejoicing in Stein’s linguistic qualities and wondering how her radical blend of repetitiveness and unpredictability might relate to the environments around us. He also had Paul Klee’s sketchbooks along, and pondered Klee’s phrase “twittering machine” as an analogy for nature’s mix of freedom and determinism. Both modern and indigenous aesthetics informed Bill’s ways of seeing, his mediation of inner and outer worlds.

Bill read, wrote and listened as a poet and a musician. His immersion in certain songs seemed to heighten his grasp of language’s power. In his cultivated, introverted way, he shared the visionary panache of the likes of Jim Morrison—the link between the beats and “Texas radio and the big beat.” During desert-listening to Morrison’s uncanny “Horse Latitudes” (nautically tinged ravings set to a backing of bewildering clamor) phantom waters seemed to surge anew in ancient sandy beds. Bill could parse such hermetic signals. They echoed his own calling. So did the bleak, loving humor of Townes Van Zandt, John Prine and Greg Brown—and the hard-hitting simplicity of straight-up blues.

Our return route took us through northeastern California, with a stop to visit the lava beds once used by Modoc warriors in their defense against the U.S. government. Standing in the shadows of a lava tube with Bill and Devon, I thought about poetry as our own means of underground resistance.**

When we arrived back at Bill’s Tenino farmhouse, completing a circuit of some 1,500 miles, it felt heartbreaking to leave him alone again. His solitude in those ramshackle walls seemed less nourishing than before. In fact, he soon moved to a wooded spot closer to town in Olympia. With new companions, he began to satisfy his naturalist wanderlust with exotic world travels as well as embarking on new American odysseys. A supporter of environmental, literary and spiritual groups, he could hold his own as a gentleman hippie. “At fifty,” he wrote, “my hair is finally long enough to plait with feathers.”

I have many more memories of Bill. These include, in later years, working with Tatyana Apraksina to translate Bill’s poem “The Mind of Taxidermy” into Russian; being a guest with Tatyana and meeting Bill’s fellow ecologist and new, beloved wife, Jeanette Barreca; discussing the work of two great Northwest Roberts—Sund and Bringhurst—with him; learning that he’d indeed reconnected with his son Matthew; reading with Bill, Greg, Tatyana and translator Jamie Olson in Olympia; being honored by his and Jeannette’s presence at Tatyana’s and my readings in Astoria, Oregon and Port Angeles; sharing a meal and celebrating Tatyana’s birthday with him at Duckburg—the floathouse colony founded by Greg and his partner in book arts, Christi Payne, on Astoria’s John Day River.

As the publisher of Radiolarian Press, Greg went on to release Bill’s first two full-length collections, This Old Riddle and Unfurl, Kite, and Veer. Greg also handled the beautiful design of Bill’s Waymaking by Moonlight: New and Selected Poems, published in 2020 by Empty Bowl Press. In the nearly thirty years that remained of Bill’s life since I first met him, his body of work and literary reputation grew steadily. He emerged as a teacher and elder statesman in his own right.

I hope these offerings may add to a potluck of impressions that others will contribute in witness to the charm and coherence of Bill’s personality and his commitments to literature, friendship, the glory of polyphonous creation, and poetry as an endless waymaking between the mythical and real. I hope, too, that others just now finding out about Bill and his work will want to join in.

Bill Yake’s earthly trail ended on December 12, 2022, but his work will endure.

* two of Yake's poems from Waymaking by Moonlight:

Aging,

we grow asymmetrical—

strength in one eye

and the opposite leg,

and our lives gyre

slowly at first,

then like old nations

we pull in our arms

and spin thin strings of fire.

Moon from Winter Ridge

The moon is a stone mirror.

We forget that.

Its reflection

from the valley

of polished water,

austere as stopped time

is the double ricochet of sunlight

banking precisely home to each attentive eye.

-- Thanks to Empty Bowl Press for permission to include "Aging" and "Moon from Winter Ridge" by Bill Yake from his collection Waymaking by Moonlight — Empty Bowl Press, 2020

** Editor's note: When I asked James to say a bit more about his sensing of poetry as resistance — was something assumed there as a matter of unspoken agreement? He replied, "I felt this at the time and may not have ever put it in words. The lava tubes were so rugged - so shadowy, cool and solemn - amid a wilderness depopulated by thoughtless history. They felt to me like spontaneous gifts from the land's psychic geography, like subterranean roadside chapels where we could permanently internalize whatever epiphanies we might have wished to claim as life-altering above ground. I suppose fighting corrosive homogenization through literary friendship is a central theme of the piece." - Richard Whittaker

About the Author

James Manteith is essayist, poet-songwriter and Russian literary translator. He serves as Translation Editor for the multidisciplinary cultural magazine Apraksin Blues, as well as Associate Editor for Mundus Artium Press and Mundus Artium: The Journal of International Letters and the Arts. He works in collaboration with his longtime mentor, the artist, author and Apraksin Blues editor-in-chief Tatyana Apraksina.

SUBSCRIBE NOW

TO OUR MONTHLY NEWSLETTER

Share Your Comments and Reflections on this Conversation:

On Mar 9, 2024 Freda Karpf wrote:

wonderful story; enviable friendships and rich bit of history. thanks for this.On Mar 7, 2024 James Mantooth wrote:

These are outstanding stories of communion among poets, including “coming of age” author James. I particularly liked the idea that poetry helps to bridge between myth and reality. The author’s use of words to describe the adventure is outstanding.On Mar 7, 2024 Robbie Mantooth wrote:

My declaration I’d take responsibility for the son whose age threatened to reject his application for the week-long writers conference he aspired to attend brought me even more insights than my own sessions could provide. These wise mentors made generosity and shared interests much more important than anyone’s chronological could limit.On May 17, 2023 kevin miller wrote:

thanks for this wonderful farewell to such a fine poet and person.