Interviewsand Articles

A Conversation with Mary King - Spiral Dance

by , Aug 31, 2023

Photo: R. Whittaker

I’d been in touch with sculptor Mary King for years, but somehow it hadn’t led to a next step. Then one afternoon, as my wife and I were on our way home from north of San Francisoo, I remembered this was the opening day of an exhibit of her late husband Kendall King’s work at San Rafael’s Falkirk Cultural Center. Perfect. Kendall, I knew, had taught painting at the California College of Arts and Crafts with the unusual twist of combining the class with a study of philosophy. So I’d get to meet Mary, as well as get a look at her husband’s work. I’d been intrigued when she’d told me earlier that philosophical inquiry had always been an integral part of their work as artists.

It was a lovely exhibit and Mary was open to a follow up visit so I’d get to see her own work. One thing led to another and I proposed an interview. —R. Whittaker

works: I’d like to get a little of your background and your husband’s and then we can move on from there.

Mary King: Well, I went to Bryn Mawr, where I majored in Philosophy—more like medieval, religious philosophy. A college friend of mine set up a blind date with a friend who also had an interest in philosophy. It was Kendall who was serving in the Pentagon and was just about to complete his service when we met. We married the winter after I graduated from college.

works: Okay. Tell me a little bit about your interest in religious philosophy.

Mary: My mother was born in India of missionary parents, and my grandmother had a big effect on me. My mother got sick when I was in my teens. I was very religious until then, but after that, I turned away from religion.

works: What were the effects your grandmother had on you?

Mary: She lived in our home after retiring and was always very attentive to me. We took the streetcar together to the Methodist church. But when my mother became ill, I didn’t think the religion she had was helping her out much. And it didn’t help me out very much, either. So I sort of let it go.

works: Do you think you were looking for something that might help you?

Mary: Well, I was always interested in ideas—and dance. Those were the two things.

works: Dance?

Mary: Dance was very much something I was interested in. When I was in college, during the summer, I studied dance with Martha Graham at the Connecticut College School for Dance

works: Did you actually work with Martha Graham?

Mary: I didn’t work with her, but I was in her classes. She taught me a lesson. Coming up to me in one of the classes, she said, “Stand up straight.” Then when I tried, she said, “No. That’s not right. But if you’re going to make a mistake, make it a big one, so you know what it is.” That’s always hovered over me as a sculptor, you know.

works: How interesting.

Mary: If you choose the wrong material, go down the wrong path, or make a form that isn’t working—make it strong, so that you can tell what’s wrong with it. Then you can make the correction.

And José Limón was there that summer, too. So those were my inspirations.

I was thinking of switching from Bryn Mawr to another school to study dance, and I thought I’d take this summer class to find out. I found out that I didn’t have enough stamina to dance ten or twelve hours a day. So I stayed on at Bryn Mawr. But I kept dancing until my knees gave out when I was around 25. I had a lot of knee trouble.

works: What was it about dance that attracted you?

Mary: That’s a good question. How to have your body express your feeling, I think. That was it mostly, how to be true in movement to the feeling you’re having. And of course, having had that study and practice of dance helped me when I got into figurative sculpture—that’s what I started with, making figures. As a child, I made my own dolls and doll clothes, and did a lot of sewing. Sewing helps you learn sculpture, too—how to round a corner or make a fold in the material that will work.

works: That’s interesting. Earlier in my life, I was married to a gifted woman who made dolls and doll clothes when she was a kid. Then she got into painting in college, but eventually ended up designing dresses and started a dress company. It was her art.

Mary: Well, and that has to do with paying attention to the figure, too.

works: She said a quarter-inch made a difference.

Mary: Yes. Anyway, when I finished college, Ken and I got married. We both went to work in Washington. When he got out of the service he wanted to get his PhD in Philosophy—and he did—from the University of Michigan. I worked and saw him through that.

works: Let’s back up little. You said your experience in dance informs your sculpture, and what can you say about how that works?

Mary: I didn’t ever do much drawing as an art person, but I understood the body because I’d been a dancer.

works: Can you say something more about that?

Mary: Again, I think it’s a question of expression of emotion that one may have, and how that filters through the movement that you make with your body.

works: Then when you express your emotion with your body, you become more aware of the actual shape your body takes, or wants to take.

Mary: Yes, exactly. But also, as I said, I’ve been an idea person, too. After working with the figure a lot, I started to use masks with the figures because that sort of saves you from revealing everything. There’s a hiding of some of what’s internal, and even though it may come through in your body, it’s somehow closed off. There’s a combination of awareness and truth, and protective measures to hold yourself together.

works: That’s interesting. Could you reflect a little more on the expression of the most intimate, important feelings of oneself through art or dance, but also the importance of—or the necessity of—also protecting something? So, there are two sides—showing and holding back. On the other hand, perhaps it could be helpful to other people to see some of these deeper things. What are your thoughts around that?

Mary: I think it’s the dichotomy of life. The negative and positive, the hidden and the open, the contrariness of experience and being alive, is something that’s always been a question for me—and how to balance those things out. And that led into—which you don’t see much here in the condo—how in my mature work with the large sculptures, I chose to work with rocking forms, which have that question of balance, of being off-balance or on balance. Or going from one pole to another pole. So that’s been consistent throughout my experience as a maker in dance, and in sculpture.

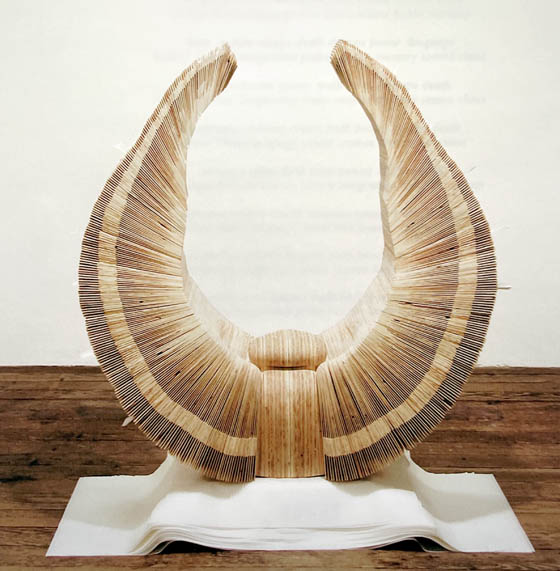

Fanblotter Rocker with Notes in Invisible Ink, 2002, 60" x 58" x 24"

works: A central thing. Okay. And you started telling me about getting married to Kendall. What year was that? [1955] And you helped him get through to his doctorate.

Mary: Yeah, he got through and I kept working. Then after he got his doctorate, he had a teaching job in Dekalb at Northern Illinois University. He taught there for seven years in philosophy.

works: What was his area of philosophy?

Mary: At that time, Logical Positivism was the big deal. But while he was teaching, he was also drawing and painting all the time. That was his kind of release. We were about 30 miles from Chicago and he took some painting courses at the Art Institute there. And gradually, he decided he’d like to get further with art and teach both art and philosophy. So, we both had this dichotomy of experience that doesn’t seem to match up—philosophy and art. Maybe it does for some people.

He was a great admirer of Diebenkorn’s work and he decided to try to get a degree here at the San Francisco Art Institute where Diebenkorn was teaching. So we came out to the Bay Area.

works: Okay. Let’s look at some of the things you’ve brought up. It’s very interesting that you both had these two sides. You with the expression of feeling in dance, and with religious philosophy. And Kendall had a similar dichotomy. I’m guessing that through art, he must have been contacting his feeling. In philosophy, Logical Positivism strikes me as a pretty dry area.

Mary: He was very interested in Wittgenstein, too.

works: Who was a remarkable thinker.

Mary: Do you understand much about him?

works: A little. He was a major figure in 20th Century philosophy, right there with Heidegger. My younger brother got his PhD at Yale on Wittgenstein, and we had many long conversations around that. Was Kendall interested in Wittgenstein’s later thought?

Mary: Yes. I think so. But he did pursue art more. I think art served his thinking, as well as philosophy.

works: What do you think your husband got most deeply from making art?

Mary: I can’t pin it down because he didn’t verbalize a lot about his experience in art. What the exhibit at Falkirk [in San Rafael CA] didn’t show was how amazingly he could draw. He was a great draftsman, and I have tons of his work as a draftsman, which could be a show in itself, maybe in the future.

works: What do you think it was about Diebenkorn’s work that attracted him?

Mary: I think it was that combination. I mean, Diebenkorn was also a draftsman, and he seemed to have ideas that informed what he would draw, and the way he would present what he saw. It wasn’t necessarily photographic.

works: So he was attracted to Diebenkorn’s ideas, but maybe to the beauty of his work, too.

Mary: I think you’ve articulated it well. He liked painting the natural world. He would photograph things and then work from a photograph. He never graphed it. I don’t know if you remember the painting in the show of the seashore that had the spiral that disrupts the presentation of the image, in a way. It’s also the idea of the movement of wave and the rotation of the tides.

works: I thought it was one of the strongest paintings in the show. Looking at it, you can’t just have the simple dream of a beautiful landscape. There’s also this mystery of experience, a moment of beauty, but my life is something ongoing, and it’s not always beautiful.

Mary: The word ‘mystery’… It’s the mystery of the visual experience. And in dreams we have very visual images. But there’s the mystery.

works: Yes. And some of his paintings clearly bring the mystery forward. Would you say he was a seeker?

Mary: Definitely. He was interested in psychology, too. After he got his MFA from the Art Institute, he taught at CCAC. He was teaching both philosophy and art there. It’s what he’d wanted to do, but he found that the students didn’t really want to talk philosophy.

works: I’m intrigued by your both being visual artists and also having a strong life in ideas.

Mary: I was always aware of the verbal element in my thinking.

works: Can you say more about that?

Mary: It’s hard to be articulate, and here I am talking about how important words are. When I’m working in my studio, there’s constant commentary going on. I wonder what I’m doing; what am I making? How to describe it, find the truth in it?

works: The search for the truth. You’re making something, and it’s emerging. Right? So you don’t always know where it’s going.

Mary: That’s right.

works: And as it takes shape, what does it mean?

Mary: Well, I’ve always said that once I got started with something—with a material or with an idea that I had—often I’ll have ideas, or dreams and visual images, I’d like to try out. When you get started with the actual hands-on, this thing becomes itself and I’m sort of just the manipulator. I’m not necessarily guiding it. I might be. And sometimes when I try, it doesn’t work.

works: Am I making myself to some extent when I’m making art?

Mary: That’s a good question. Well, then you have to explain yourself. You have to tell yourself what you’re doing in words. I think that was really important and it just stuck with me.

works: Maybe it’s something that has its own value.

Mary: I think I valued it, because when you try to articulate, you can let it go—like you do with an image. With an object that becomes itself, you can see it. It then becomes an image outside of you. It’s more than you. You can write words down on paper. You can pay attention to whether they’re matching what you meant, what you’re looking for, or articulate the question well.

I’m interested in the question. If you get the question right, then that leads to the next experience, which may lead to another question, and not necessarily to some kind of a defined answer.

I’m more interested in the spiral than I am in the circle. The circle encloses. It may contain, but it may also shut off another question, whereas a spiral allows that question to flow more freely.

works: That seems so important in life, having real questions. Answers close the door.

Mary: And that’s fine. I mean that’s all right, but that isn’t the way I work.

works: And you said that sometimes the piece is more than I am.

Mary: Usually.

works: So that’s fascinating, because something has come through you, and “it’s more than I am.” But it came through you.

Mary: Yes, you’re the facilitator.

works: So that sounds kind of mysterious.

Elevated Conversation Rocker, 2000, 97" x 47" x 20"

Mary: One of the things being in this environment that’s so different from having our studios and working all the time, is that it’s a different experience. I’m working with text and ideas now, and one of the things I thought I would do is write about the work that I’ve done. But that’s going back, and I feel like I’ve still got some time and energy to go forward a bit. Getting through Ken’s show took a lot of work, and I want to move forward and do more of my own work.

works: Do you mind if I ask how old you are?

Mary: I’m 89. [she turned 90 a few weeks after our conversation.]

Works: Well, that’s amazing, and you’re so alive!

Mary: Ken was 91 when he passed last year. I kept a journal with some of the questions that came up and phrases that come up for what I’m trying to find out. I’m amazed at what can come up, you know?

works: Can you share any examples?

Mary: Oh, boy. Well, even titling pieces like, Dawn Now, Dusk Now and The Back of Now is Empty, but We Dream to Reach Up. That’s the bronze sculpture out there just outside, and inscribed inside is “the back of now is empty.” What I was thinking was the face is “now” and the back of it is empty. There’s no face on the back side, so the “back of now is empty.” And that’s kind of an idea to explore, too. “Dream to reach up” is part of the inscription. I think if something is empty, you might also want to fill it up again, or go up again in it.

works: “We dream to reach up.” That’s a beautiful.

Mary: I think that’s something I may have written down while I was making this sculpture before I knew what the sculpture was about. The fact that I was using different phases in time—well that’s another element, how time figures into the making of something.

Often, I would work on three or four things at the same time to allow refreshment in my own head about a particular piece not knowing where I was going—where the next step was going. I’m afraid I’m not as articulate as I used to be.

works: You’re very articulate.

Mary: That was the show at the Oakland Museum.

works: What’s the place in your life of close artist friends? Patricia Stroud is a friend, right?

Mary: Yes. Pat and I got to know one another when I was at the College of Marin, learning how to do bronze casting. That was a long time ago. What was interesting between us, was this thing of having ideas and questions that lead us on in our work. Also, the handling of materials. I mean, we both enjoyed the physical work.

We knew we were different from most other women in that way, having the skills to use the tools you need as a sculptor. That was one of the things we had that was a little special. Also, I had never had a friend with whom I could talk about not knowing where I’m going in making something. That going ever onward to discover what would come forth was a track we were both on at the same time.

works: What do you think it is that one gets from working with one’s hands?

Mary: Well, it’s something I’ve always done. I’ve always used my hands making things. Why does somebody want to make something? It’s a big question.

works: It is a big question. I think it’s important.

Mary: I’m still asking that question, actually. I’m trying to explain that to myself in words, and I don’t think I know all the answers. I’m still exploring and trying to find out why. I like showing my work because people comment. I’ll be amazed at their reactions and their interpretations, and what they find. I find it so pleasing. It doesn’t need to have an explanation from the artist. That’s where the circle and spiral come in. I feel that when you show, you’re on a spiral curve.

works: Right. You’re moving in a third dimension and always traveling through new territory. So it’s a circle on a journey, which is how our lives are as we tend to repeat things.

Mary: Yes, and it can go up or down.

works: How can you tell what direction it’s going?

Mary: Sometimes you don’t know and you try to figure that out.

works: How could you tell when it was going down?

Mary: You might be getting into difficult territory, something that’s trying to be protected.

works: Not ready to be seen?

Mary: Not ready, or not able, to be seen—not uncoverable yet.

works: So if it’s going up, how do you tell?

Mary: Reaching. If it’s still reaching you keep going. It’s interesting that my husband wrote this on his paper napkin “keep on going.” It was his mantra the last few months of his life. It was true for both of us.

works: Getting back to the hands. Sometimes I feel I’m actually getting some kind of nourishment through my hands.

Mary: Do you work with your hands? Do you make sculpture?

works: I’ve painted and thrown pots, made sculpture and furniture. I do yardwork. I do a lot of stuff with my hands. I was a carpenter for a while. I did plumbing and tile setting. I love working with my hands and as I’ve gotten older, I’ve recognized that there’s just something nourishing about it.

Mary: That was one of the things in dance that always interested me. When I see dance, I’m always seeing what the hand is doing, you know—how it’s held. Whether it’s a special way because of ballet, a special position, or whether it’s an extension of the movement of the whole body. There again, you have the distinction between rules and behaviors, between what’s natural and what’s designed, imposed.

works: Yes. I think a lot of people are living in a kind of despair. They may not even know it. There’s a loss of meaning living in a world of things we’re always being seduced by that can’t deliver what’s promised. And working in a job one doesn’t love—just a lot of despair, I think.

Mary: I think the pandemic has increased people’s awareness of their own despair, probably.

works: Do you feel it’s fortunate having a life in which art has been so much a part of it?

Mary: Yes, I do feel that, but I also feel like I’ve been away from it for several years. I mean, because Ken was failing when we moved here, these last two years have been really a challenge. I was physically doing a lot, which kept me going. Actually, it kept my body going. I’ve had some challenges and accidents and so on, but I’m really still in there physically. I mean I still want to keep working.

works: What are some of the things your husband would say about why art making was so important to him?

Mary: It was partly his own response to what he could see and hear. He was very interested in music from Classical to Jazz, to anything. Those line drawings in the show were the last things he was doing. And a lot of times, he was listening to music while he was working. I don’t do that. I do words.

works: Do any particular words come to you right now?

Mary: There were often words that would come to me when I was cutting into something—are these the wounds that make it brave?

works: Are these the wounds that make…?

Mary: I’d be thinking of the form I was carving or shaping being something brave. When you make a cut into it, are you being brave?

works: And bravery, do you have some thoughts about bravery?

Mary: Very much. Of the thing that’s becoming itself. I’ve used that term a lot, you know. Whatever is being made is becoming itself. I’m not making it; it’s become itself. It has a destiny of its own. And bravery is taking the hits and cuts that it gets in the process of being shaped. You know, I’ll make a shape and, “how high it will it go?”

works: How high was it brave enough to go? Is that what you meant?

Mary: Right.

works: Is it required to be brave to become what you are?

Mary: Maybe. I hadn’t thought of it in those terms. But I think that’s something important. [she pauses]

I think to be what one is, you have to be dedicated to work, and to be as truthful as possible when making something—and to allow failure, or hiding, to protect a truth not yet ready to be revealed.

About the Author

Richard Whittaker is the founding editor of works & conversations and West Coast editor of Parabola magazine.

SUBSCRIBE NOW

TO OUR MONTHLY NEWSLETTER

Share Your Comments and Reflections on this Conversation:

On Mar 11, 2024 Bruce Morgan wrote:

I define all creative endeavors as conceptionalizations of felt or imagined experience. As such, they are divorced from true reality. And therefore, the importance of using hands and body to shape our creations stands out as a way of connecting the inner self to its outer dimension. Sadly, it is often more frustrating than enlightening and the struggle serves a self-defeating role, further divorcing the realm of the mind from the physical realm. Through spontaneity, there is some relief from this dilemma, yet never have I been able to break free from the dichotomy. That artists and thinkers try speaks to that bravery that is referenced in the interview. Brave to try, for failure is surely to come.On Mar 9, 2024 Freda Karpf wrote:

On Mar 9, 2024 Freda Karpf wrote:"Am I making myself to some extent when I’m making art?" from the interviewing - what a great question. This interview has such a great weave of back and forth with the "artist" also asking Richard wonderful questions. And I imagine that the process for working with your hands, which I think writers also do (a faint plug for myself and other writers - because writing is very physical also), is another way of knowing the world and becoming.

On Mar 7, 2024 Lori McCray wrote:

It's been such a pleasure to read this backing and forthing. It's taken a lot of bravery for me to become who I am. And as your dear husband said, Mary, I keep on going. Blessings to you, and Richard too.