Interviewsand Articles

A Conversation with Doug Groves: Ranch Life

by Richard Whittaker, Jan 2, 2005

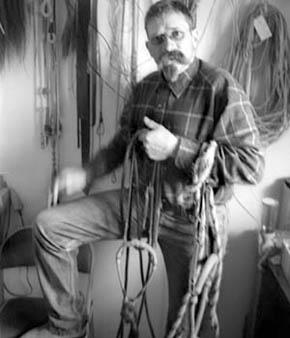

Doug Groves welcomed Andy Boyer and me into his house on the 400,000 acre TS ranch some 40 miles west of Elko Nevada. Groves is one of the masters of braiding rawhide into the elegant tack that's part of the buckaroo tradition. Andy had asked ahead of time if Groves was open to an interview and he graciously agreed. He happened to be working on a set of reins - on a part called a “button,” which is an intricate feature that's decorative and adds balance. Groves suggested he just keep braiding while we talked. I picked up a set of reins he’d braided that were sitting on the table in front of me.

Richard Whittaker: These are beautiful.

Doug Groves: They’re eight strand reins with a twelve strand romal. They go to a friend of mine Terry Sullivan. He’s the sergeant at arms of the state legislature. He’s got quite a few pieces of mine. These have a substantial number of buttons on them.

RW: This is a romal?

DG: This will be hooked on to your bridle. I’ll get a piece and show you. [comes back with a bridle with reins and romal] The romal is used to encourage the horse if he needs it, or to hit a cow if it’s going too slow. That’s the way they’re used. Reins and romal. Now that’s a traditional California bridle outfit.

Then I’ve got bosals. [picks up another braided piece] This would be on the horse’s head, just like that. If the horse was in the training process, you’d be riding him with your two-rein just like this and your reins would be hanging loose and just wrapped over your saddle horn.

RW: I wonder how you got into the ranch life, the cowboy life. Would you say that you’re a “buckaroo?”

DG: Yes, I’m a buckaroo. Well, I was raised in town, but my family are farmers from Idaho. My mother’s family and my dad, they all grew up on farms in Idaho, but my father left and became a Safeway store manager. When I was a kid, I wanted to be a cowboy. I was really lucky, Richard, I never deviated from that. I grew up watching those guys on TV and thought, that’s what I’m going to do someday! Luckily we moved to Nevada and I got me a job working for a cow outfit, the 7S which is east of Elko. I worked for a fellow named Johnny Welch who was the cow boss there.

RW: So you would have been about sixteen?

DG: I was fourteen, and working for a hundred and twenty five bucks a month. I didn’t even know how to saddle a horse. I knew absolutely nothing. But they gave me a chance. I worked there that summer, and the next summer I took a job at the I L ranch. It’s north of Elko about a hundred miles.

Every summer while I was in school, I would take a job working on one of these ranches and I’d learn a little bit more about cowboying. I figured part of that was rodeoing, so I rode bucking horses in high school in rodeos and I rode bareback, too. Boy when you’re a kid, that’s a lot of fun! But I always worked on ranches. I really liked cattle, and I liked horses, and I liked being out on a ranch. I didn’t like town much. I went to college for a little while and kept on with the ranch throughout the summers, and then I quit school.

RW: So you always wanted to be a cowboy, you liked horses, you liked cattle—what are your earliest recollections of connecting with animals?

DG: Well, as a kid we had chickens and stuff like that. We never had horses. My uncle had a ranch up near Silver City, Idaho. He was quite an old guy, an Idaho rancher up there. When I was a tiny little kid, I’d see horses on TV and my parents said, well, we’ll take you over to Uncle Elmer’s and let you see a real horse. So we went over to Uncle Elmer’s and, God!, they had them horses in a barn. There were double doors and I can remember sitting there and waiting and waiting. Now I’d never really seen a real horse before, and they were big, you know. I was waiting and watching, and pretty soon here they’re shaking a grain bucket beside me. It was just an old, gentle horse, you know, but God! he heard the grain bucket and here he comes! He run as fast as he could and stuck his head right up in front of us. Well, I was just a little kid, and it just scared me to death! Just practically traumatized me, you know? So that was my first experience with a horse! It scared me pretty bad, but I guess I got over it. I’m still a little scared of them, though.

RW: But you like horses anyway, I take it, and you like cattle.

DG: Yes. I like horses and cattle, and you know, Richard, I like the animal husbandry part of it. I like to be responsible for large numbers of cattle. I like that.

RW: I think Andy told me you’re the cow boss.

DG: Yes, sir.

RW: Which means you are responsible for all that, right?

DG: That’s right. For the herd’s health. My boss says that I’m responsible for everything on this ranch on four feet with a heartbeat.

RW: How many animals does that amount to?

DG: On this ranch, we run four thousand head of cattle and we have about sixty head of horses.

RW: How many men do you need here?

DG: This time of year [January, snow on the ground] we’ll only have four or five guys, and then when things get busy in the summertime with branding and stuff, we’ll have probably eight guys.

RW: So you started out at about fourteen…

DG: And I’m forty-six now. But during that time, I quit cowboying, got married and worked in a lumberyard. I also gold-mined for about three years. When I quit gold-mining, I went back to cowboying. That must have been when I was about twenty-eight. So that’s almost twenty years. I’ve been horseback since then.

Now I started braiding when I was at the MC Ranch. I was about nineteen. An old gentlemen I knew by name of Frank Hansen, one of the premier old braiders, he got me started, taught me how to judge good rawhide; that’s a critical part, being able to judge good hides. There’s so much that goes into braiding that by the time you get to this point right here, [holding up the braiding] if it ain’t good hide, you’re in trouble. He helped me learn all that.

RW: What was it about braiding that you took to it?

DG: Well, I always wanted nice horse gear. You know, it’s so damn hard to find good quality horse gear! The reason being, these horses, the way God designed horses, they can feel a fly crawling down their back! That’s how sensitive they are. So when you’re trying to send a signal to a horse, with a set of reins or a hackamore, it needs to be extremely light. The reins have to have a lot of body and feel to them, because that horse feels every signal you’re trying to send him. So you want a quick response, a quick release, so that horse feels the pressure and release just as quick and as easy as he can. So by having really good quality gear, you can accomplish that a lot better.

RW: So when you hand-braid these there’s something about the flex or the lack of flex. It bends a little differently? This is a real craft, in other words.

DG: Exactly. And good horsemen, if you’re making a good product, they’re going to hunt you down, because they want the best gear for their horse. That gives them an advantage with their horse, so they’re going to want your gear.

RW: Now you’re one of those people they hunt down, right?

DG: Well, yes. I get more orders than I can stand. I try not to even take more orders for that reason. What I do is I write people’s names down and I say, well, when I get something done, I’ll call you and let you know.

RW: I’m wondering, was there anything about the actual braiding that appealed to you?

DG: Yes. I was fascinated by the fact that you could take a bloody old cowhide… I’ll tell you another thing that really appealed to me: there wasn’t a whole lot of overhead! I can take a dead cow, and this basically is the ultimate recycling; you’re taking a non-usable animal, one that dies or has to be put down, and converting it into something like this, a functional piece of horse gear, or even to a higher level, to art work.

RW: Now that’s something!

DG: Yes. So I was just absolutely amazed, Richard, when I looked at that, looked at those braiders’ work. You would look at an old bloody cowhide on the ground and you’d say, Doggone! How the heck…? You know? The process of getting to that point, I think, is what really intrigued me. I said, man, I gotta learn how to do that!

And then it’s an occupational art, I’ve always thought. You’re exposed to it because you use quality horse gear when you’re working your horses, and you’re exposed to other people in your everyday work who may be rawhiders or who know someone else who does.

So the learning process is taking place on the ranch while you’re there like I was as a young fellow knocking around these ranches. And the ranch industry has changed—there’s not near as many big ranches or opportunities for jobs like they used to have. Back in the seventies when I was a kid, they all ran oh, gosh, five to seven men crews. Someone like me who wanted to learn rawhiding, well, you’d try to get somewhere where there’s maybe somebody you knew or you’d heard of who was a pretty damn good rawhider because when you got there you could hang out with him, and you’d learn some stuff from him! So that was always something I’d think of because basically this is always taught one-on-one. Like so many crafts, it’s really hard to teach. You just need someone there looking over your shoulder and helping you learn to do it. So it was an occupational art where you could always be around people who did it on these ranches.

RW: This is the old apprentice style of learning, which goes very far back. There must be something pretty satisfying about that.

DG: Oh, yes. It’s been very rewarding for me. I enjoy doing it. I’ll tell you the most rewarding thing for me is that I’ve really enjoyed having the opportunity to help a few people get started myself. You know, realistically, all this talent, I mean I don’t care who you are, everything you’ve got is on loan from God, you know. You can get knocked in the head tomorrow and forget everything you ever knew! When you start forgetting something like this, boy that’s pretty hard.

RW: The craft will be forgotten, you mean.

DG: Yes. And there’s so many people out there who are real stingy with their knowledge and their abilities. They won’t teach anybody nothing! Now I don’t do a lot for a lot of people. I’m too danged busy, but if I can teach them something that I know, by golly, I’ll teach them! I have very few secrets, because now that I’ve been braiding for oh, about twenty-six years, twenty-seven, my hands hurt so bad, and it takes me so long, that I’ve come to the realization that I can tell you everything you want to know, any trick that I might know, and neither one of us are going to flood the market! Quality rawhide work is in such demand that we’ll always have a home for everything we make. So I feel real free in teaching you anything you want to know. I’m not in danger of losing my market. And I think that’s what it’s all about. If the good Lord gives you that talent, you better share it! He can take it from you at any time.

RW: That’s very generous. It’s not an attitude that everybody has.

DG: No. We’re just here for a short time and you better enjoy it and pass along what you’ve got. It ain’t yours, anyway.

RW: Now when you’re not out there watching over things and you have some time of your own, I take it that’s when you may want to do some braiding.

DG: That is. And you know, it’s a pretty intense deal. You got to plan for it because rawhide, it’s got to be damp, what we call “tempered” or cased, just like working with leather. You’ve got to work when the rawhide is right. So you’ve got to plan way ahead, and have your eye on it when there’s time to work with it.

RW: So the rawhide can be…

DG: …either too wet or too dry, so you’ve got to plan far enough in advance. But we’re pretty lucky now because we’ve got refrigerators and we can kind of get things in our favor, so to speak. The old-timers didn’t have all the advantages we’ve got.

RW: Is there an advantage to rawhide over leather? Now I didn’t know the difference, but Andy told me.

DG: Yes. Leather has been chemically processed and rawhide hasn’t been. Most people don’t know that. It’s the feel. It’s all about feel. Now those are a set of leather reins and those are sewing machine belting, those there. If you just feel those, Richard, [handing them to me] and then feel these. [handing me a braided rawhide set] You see what I mean?

RW: Yes. I can feel the difference.

DG: Now that’s the rawhide. The leather here, now those are OK, but there’s no life in them like there is in the rawhide. You see? And we’re talking about animals. You know the way we are, we treat horses—we don’t realize how sensitive these animals are! We’ve got our big old lard-ass up there on that horse and we’re a pullin’ and a doin’ this and doin’ that, and we don’t realize if we just slow down and just send him a little bit of a signal, he’ll respond to it!

RW: Animals are more sensitive than people realize.

DG: Oh, I’d agree!

RW: Now I don’t think most people have really seen this first-hand. Maybe they’re man-handling their animals, but they wouldn’t need to do that, if they understood something else.

DG: And we’re guilty of that in our industry because sometimes what happens to us, like with so many people, we have a project ahead of us and a goal to reach and sometimes our horsemanship suffers for the sake of getting your butt up there and turning those cows! Making sure they go through the right gate and not the wrong one.

Now is that straight enough Andy? [hands the braiding over to Andy for him to check it]

Sometimes our horsemanship suffers for the sake of getting our work done. It’s a real fine line. In our business, we’ve got to be cowboys first, because that’s what they’re paying us to be, but also, the better the horses we can make, then our job is a pleasure, and the thing goes so much smoother. So we’re also horse trainers or horsemen. That’s where the private craft comes in.

RW: Well, I happened to run into a cowboy in Elko, a black cowboy named Jim Brooks, and I got to talking with him, a real nice guy. We were talking about horses, and he said no real cowboy ever abuses an animal, but he has to be in charge. He says once the animal responds, you stop pulling or whatever, immediately.

DG: Exactly right. Now Jim Brooks, he was kind of a legend. He worked here probably in the early seventies. He came to this country, to a notoriously tough outfit up there, the Spanish Ranch.

RW: He says he was always given the worst horses.

DG: Yes. They couldn’t buck him off. The boss got mad because he always prided himself on if somebody new came up there, he’d get him bucked off. He couldn’t buck this Jim Brooks off. This guy’s tougher than heck. Now I’ve never had the pleasure of meeting this man, but I’ve heard of him all my life. I’d love to meet him! He was before my time. They said this guy could really ride bucking horses.

Now Andy, what do you think? [handing him the braiding again.]

You know, that’s the thing I always kid about. You know, all these other cowboys can out rope me because while they were out practicing ropin’ in the evenings around the camps, I was in the damn bunkhouse trying to tie these doggone buttons. So consequently I can do a pretty good job rawhidin’ but I can’t rope worth a damn!

The real trick is being able to cut good string. That’s a real big part of it.

RW: So this is all string you have cut yourself.

DG: Yes. I’m going to do a little more here, then I’m going to go show you how we do that. I’ve got some we can cut right quick. It’s quite a process from killing the cow, or finding a dead calf, and going clear through to this stage here where you’ve got the product, and you’re actually finishing it. I figure that on a set of reins, I would venture to say that I’ve got eighty hours.

RW: You’ve got eighty hours, but if Andy—and no slight to you Andy—if Andy does it maybe he’s got a couple hundred hours in it because he hasn’t been braiding for nearly as long.

Andy Boyer: And it won’t be the same quality.

DG: But it will be distinct. When Andy eventually puts in more time and gets better and better, his work will always have his distinct mark just like any other artist’s will. He will have a distinct button or a distinct way he does something that will always identify his work to the careful eye. That’s why the collectors come along. All of the sudden, you see collector value because the pieces are as unique as the people who make them.

You know, you can go into a place with stuff that isn’t worth a damn, but then when you see a set of Bill Dorrance’s reins here, and a hackamore from Bill Bud there, and a set of reins that Les Morgan made over there, then all of the sudden, history comes into it; folklore comes into it; those guys’ reputation comes into it.

See, when you used to sit around the bunkhouse, just like we’re doing with this button here, you know what you’d do? You’d sit around and someone would teach you. As a matter of fact, Roger Fisher taught me this button. OK. Well, Roger, who taught you? Oh, Gary Takus. Well who taught Gary? Les Morgan. Well, who’s Les Morgan? Oh, he used to be the buckaroo boss at Twenty-Five. He was there when the Marvels had it. The Marvels, now what about them? Pretty soon you start unraveling the whole history of the ranch industry through the people who were involved, through their craft.

RW: This enriches something, doesn’t it?

DG: Oh yes! It’s like one of grandma’s quilts or something then, because it means something to you. And you go clear beyond that, “Oh, he worked for Marvels years and years ago.” Then somebody else is going to say, “Remember those JHL horses? Well, those were some horses that the Marvels raised out there.” So pretty soon you’re going to be talking about JHL horses and the cows and the history of the Twenty-Five Ranch. See, it just opens this whole thing up! So that’s the folklore part, and the folklore part goes with it. That’s always been my take on it.

RW: I hear that in the buckaroo tradition, there’s a pride, a real feeling for the equipment that reflects the care for the animals, the horsemanship, the quality of how things are done and that, in a way, this is a culture where a craft and an art is integrated with the life of the people as they actually lead it.

DG: Yes. Exactly.

RW: That’s something special, isn’t it?

DG: That is, Richard. I never thought about it that way.

RW: Would you say that the buckaroo appreciates this?

DG: They all use the gear and appreciate it. Some guys don’t have the patience for it and don’t want to learn how to do it. When I was a kid, see, everybody had their talent. If one guy wasn’t a rawhider, he might be a horsehair twister; he had ropes, or something. It seemed like everybody had a talent of some nature. You had time on your hands around the bunkhouse. You didn’t get TV usually, but everyone had crafts and that was how they’d spend their time. The crafts go way back.

RW: Well, here’s another thing. If a guy twists horsehair, I’m betting that he really appreciates the rawhiding, the silversmithing, the saddle making and everything else.

DG: Oh, Yes. And there are some of these guys who do it all! And they’re extremely talented at it. My hat’s off to them. [turning to Andy] Now what we’re doing… [Groves is tugging at the weave] The trick here, is to make things as straight as we can. Someone with a discriminating eye, like Andy, will come along and pick it to pieces! So you have to be damn careful! [handing it over] Is that going to be straight enough Andy? We can still wiggle it around a little bit. We made an over-two, under-two pass so far. What we’re trying to do is tie this button right, Richard.

RW: What amazes me is where does the end of the string go?

DG: That’s one of the fine points, hiding those ends. Is it going to work Andy? [Andy’s not talking] It’s off a little, but not bad. I think we can correct it. How much time do you guys have? [Plenty] Okay, I won’t get in too big a hurry, then. Let me see what we can do with this.

Earlier today a friend of mine, CJ Hadley, from Range Magazine came by. We had quite a nice visit. She publishes it out of Carson City. Are you familiar with that magazine?

RW: No, but I think I saw a copy of it in the last couple of days.

DG: It’s an interesting magazine. Pretty controversial.

RW: Why is that?

DG: Land use. It leans, of course, towards ranching.

RW: I saw a magazine a while back, which was put together by some ranchers, and it took the position that there ought to be some common ground between ranchers and environmentalists.

DG: Well, this is what I see. I think that’s what needs to happen. What I saw this past weekend is what scares me. These hunting people, they are the ones with the money. Man, if they want to put a ranch out of business, they’re going to do it! There’s a lot of money in hunting. One poor little rancher, he ain’t going to fight them off so well.

RW: How do the ranchers keep it going, anyway?

DG: Well a lot of them do and a lot of them don’t. Economically, it’s not a high dollar business. Boy, them mom and pop operations, it’s hard for them to make a go of it! That’s why so many of the kids leave home and they never come back. Agriculture, the way I see it and growing up the way I did, it skips a generation. The kids raised in it grow up working so damn hard that they don’t want nothing to do with it. Then the next generation, usually they’ll come home and visit grandma and grandpa, visit the ranch and they’ll fall in love with it. They’ll want to return to that. In my case, that’s what happened.

RW: What do you think of this Elko event?

DG: I think it’s tremendous! It’s wonderful, because we need to celebrate one of the most special icons in the world, the American Cowboy. I have so been so blessed by the grace of God to be involved like I have with this! I love it! And I love the opportunity to share with people! And you know what? You can come to Elko; you can put on a hat and boots, and for a few days here, you can be a cowboy just like anybody else! I think that’s wonderful.

RW: Well, it’s starting to rub off on me a little! [laughs]

DG: I’ll tell you what, Richard. It’s something that we’re missing in society today. Now you think back a little. When you grew up, and I grew up and Andy did, we were the last generation to grow up with those true cowboy heroes. You remember it was so cut and dry. You knew good from bad. There was none of this Miami Vice crap, that kind of stuff.

RW: Can you say more about what we’re missing?

DG: Well, the work ethic. Agriculture. The care of animals and livestock. I think that’s something we’re missing today. You know what, you don’t eat until the doggone cows eat! That kind of attitude.

RW: What about this relationship with animals and the land?

DG: There’s something spiritual about that. When you look at Cain and Abel, one was a farmer and one was a stockman. So that goes way back to the roots of man. So there’s something real spiritual about working with land, and working with livestock. There’s something that people feel, and it’s a feeling that they need. We get so far removed from our roots living in these cities. We don’t smell the dirt. There are some things a guy needs to smell and taste. It’s something that’s really missing.

RW: And we’re not going to get that from a TV.

DG: No. I mean I really enjoy that TV, too. But boy, when I’m sitting in front of it, I feel guilty. Don’t you Andy?

AB: Well, we don’t have a TV.

DG: See, well there you are! [laughs] I think that in our lifestyle, we are actually further removed from society than our counterparts were a hundred years ago. See, a hundred years ago everyone traveled by horseback and was around livestock. My father’s generation, every kid had access to a ranch or a farm because their in-laws or their grandparents or aunt and uncle, someone had a farm. Heck, most of those kids could hook up a team. They knew how to do stuff. They could fix fence, feed chickens, milk a cow. That’s all gone. That’s so gone, and it’s so basic.

You know, it’s really something to bring these town kids out here. When we’re calving heifers and stuff, we’ll bring some of these kids out from town and let them see what we’re doing, and boy, they just light up! Getting to see something like that; that takes us back to this human need. The way God designed people, he designed us with a desire and a need to take care of, and to care for, animals! You really see that with them kids!

RW: That’s got to be true. It looks like you’re doing pretty good with that. [the romal button]

DG: This is the third pass. This is an over-three and an under-three. We’ll get through with this and then see where we are. We’ll have to put in a fourth string somewhere here, but we’ll get this pass in and then kind of evaluate. [handing it over] Andy, take a look here and see what you think. Now the bottom here, you probably know how to do this…

AB: …No.

DG: Well, you will. We’re going to be tight here and loose here. So that means we’re going to run our fourth string in starting about here. Half of the button will be four strings and half will be three. This used to drive me absolutely nuts. Now what really gets you [looking very closely at the piece] is you get your mustache hair in underneath and that’ll really get your attention. Now we’ll look for straight, Andy. We’re not too bad off.

RW: Is the mustache part of the buckaroo tradition?

DG: Yes it is, Richard. They used to say that all you needed to work in Nevada was a mustache and a bad attitude, and I had both for a long damn time! I guess that’s why I’ve been so successful! ∆

About the Author

Richard Whittaker is the founding editor of works & conversations and West Coat editor of Parabola magazine

SUBSCRIBE NOW

TO OUR MONTHLY NEWSLETTER

Share Your Comments and Reflections on this Conversation:

On Apr 23, 2011 Ross Knox wrote:

Doug, If you get this message,get in touch with me. Would love to catch up. 520-260-9121On Mar 1, 2009 Bobbie Yokum wrote:

I sure enjoyed reading this interview - I loved the part about rawhide braiding making people think back to earlier times. We recently lost some old cowboy friends and I hope my braiding brings back their memories through association. Thanks Doug & RichardOn Jun 27, 2008 Justin Staley wrote:

It is really nice to read about the living West and the working buckaroo. Is there any way to get my hands on more write ups like this? Thanks