Interviewsand Articles

Elko's Cowboy Poetry Gathering: Lost and Found

by Richard Whittaker, Nov 2, 2005

I’d gone into Capriola’s and wandered among too many braided reins, hats and more hats, hackamores, chaps and chinks, shirts, macates, silver trappings, hand-tooled saddles and cowboy merchandise to take it all in. Capriola’s was famous, I’d been told. Andy had mentioned it twice. He'd looked at me to see if I’d gotten it, had understood this was a place where real cowboys still came in from the range to browse the shelves for a new pair of boots or chaps and spurs.

As I walked past the glass cases and tables, the walls and hanging displays, I let my eyes pass lightly across all the tack and finery, stopping here and there. But it was a feast for someone else. What did I know of bridles and bits, riatas, hobbles and quirts? And I could find no hankering for a cowboy hat.

Macates. Is that what those coils of braided rope were called?

I reached out and held one. Made of hair, horse hair. Let’s see - "not from the tail, but the mane." Andy had told me that.

A couple of years ago, my friends Andy and Jan Boyer had moved from the Bay Area to Spring Creek, Nevada, about ten miles east of Elko. Before that, they’d rented a place on a country parcel near Sebastopol, north of San Francisco. Besides the Boyer’s place, there was the owner’s house, another cabin, a barn and an additional building or two. The property featured gardens, a little pasture with a horse and a few goats; there were ducks, a couple of dogs and cats and miscellaneous other animals.

One of the owners, Cal Seeba, conducted a practice of Chinese medicine in Santa Rosa and his wife, Arlie, ran a small business supplying organic herbs to nearby restaurants. They were all friends. Andy was the last of the four I’d gotten to know when he’d appeared as Jan’s new boyfriend. It was hard not to like Andy right away, soft-spoken and reserved, but with a hint of mischief in his ready smile. There was an element of mystery about him, too, perhaps because he didn’t talk a lot. He used to like flying hang gliders, I learned. He’d grown up a farm boy in the Midwest. It was hard to imagine Andy launching himself off a cliff and soaring above the surf crashing below on the rocky coast of the Pacific. That all belonged to a time before we’d met.

Before the Boyers left the Bay Area, my wife and I would drive up and find our way to Moonshine Road, which was the real name of it, and which I know must have amused Cal no end. Whenever we stopped in, I got accustomed to Jan prodding Andy, “Show Richard what you’ve been working on, Andy.” Then Andy would take me out back and maybe point to a black plastic garbage bag. “You know what that is?” he’d ask.

Not quite sure whether I was being joshed, I’d say, “Why don’t you tell me, Andy?”

“It’s a buffalo hide!” He’d answer, pulling the bag open and, sure enough, there’d be a big hairy thing in there sort of folded over on itself.

“Wow!” I’d offer, trying to sound upbeat and hoping I wouldn’t be asked to get a grip on the thing to drag it out for a closer look.

Another time I heard about Andy’s new job driving a horse drawn carriage. “Amazing!” I said. “How did this come about?” On another occasion, I was led out back to look at what appeared to be a sawhorse. We’d stood there in silence while, once again, I pondered whether my leg was being pulled. “What is it, Andy?” I finally had to ask.

“A roping dummy,” he said.

“Roping dummy?”

“I’m learning how to use a lasso.” Then he’d let me hold the lasso. Once, we walked out behind the Boyer’s house and there was a steer in the pasture. “That’s Boomer,” Andy had explained.

“What’s up with Boomer?”

“We’re going to eat him.”

I stood there trying to figure out how I felt about this news.

One evening we’d settled down in the living room and Jan volunteered, “Andy’s learning rawhide braiding.” I looked over at Andy.

“Is that right?” I asked, tilting my head.

It was. First he’d tanned a cowhide himself, he explained. The hair had to be scraped off and such like. We went out into the garage where he showed me the rawhide strips he’d cut in order to begin his braiding. He had to split the rawhide first though, he told me. “Rawhide braiding,” I mumbled, “Un-hunh. What do you mean, 'split it'?”

As I kept an eye on Andy trying to see where we were going, buried memories of Camp Peterkin in West Virginia were coming back. I’d been nine years old. Seemed to me we’d done some sort of braiding there. Lanyards. It’d been one of the best things about the place, actually. I’d been able to forget everything while threading the white cord under the orange one. Over this one, under the next. It was amazing what I ended up with. And I’d made it myself! I tried not to let the next thought in, though, that braiding was for kids.

One evening a few months later, up on Moonshine Road, Jan and Andy and my wife and I all sat down to beef stew. “Andy made it,” Jan said.

“It’s Boomer,” Andy announced with a smile which I couldn’t exactly decode.

Jan’s and Andy’s obvious pleasure in these fragments of ranch life was something I found quaint, a pleasant romance, and I was shocked when one day news came that they had bought a house in Eastern Nevada near Elko. They were moving to Nevada?

A few months later the first jpegs came through clogging my slow modem, photos of a simple ranch house, Jan and Andy smiling and standing in front of it against a backdrop of the Ruby Mountains. Just visible was a semi-circular, dirt driveway in an empty front yard. Completing their property, behind the house lay an equally empty acre or two of sagebrush.

We traded emails awhile, and then I didn’t hear much. Then a few months later, I ran into Jan who had returned to the Bay Area for a visit. How was it up there in Spring Creek?

Great! Andy had met some interesting people and was doing more rawhide braiding. Had I ever heard of the Cowboy Poetry Festival in Elko? I should come up next time and take it in.

Cowboy Poetry Festival? Come to think of it, I seemed to recall hearing some cowboy poet on NPR once or twice.

“Was it Waddie Mitchell?” Asked Jan. “Baxter Black?”

“I think the guy was some sort of veterinarian,” I said, “A large animal vet,” I added, as if that would clear things up.

“You ought to come up and do an article,” Jan suggested. “You’ll have a place to stay. Really. It’s fun, and we’d love to have a visitor.”

Six or seven years earlier, it happened that I’d been driving east to Boulder on Highway 80. I’d spent the night in Winnemucca and continuing on my way, by mid-morning I began noticing a shift of feeling about the landscape. Curious how that works, how changes are picked up unconsciously at first. Off to the right and ahead, a range of snow-capped peaks stretched southward - the Ruby Mountains.

It was late May and I began noticing rivulets of spring run-off reflecting the sky in winding lines across the meadows. This wasn’t the dry, desolate Nevada I knew. As I drove along, I suddenly hoped to find an exit from the Interstate before I left all this behind and found myself driving across the salt deserts of western Utah. And there it was, a little road that tucked along the base of the mountains heading south. Taking the exit, I slowed to thirty-five, twenty-five, twenty, and rolled down the windows. Now I was the only car on the road. Here and there I’d pass a barn, a house and a few smaller buildings - ranches. Now and then a pickup truck rolled by. At that speed you can see the flowers along the side of the road and hear the birds. I pulled over and stopped.

It still amazes me how much more there is to see when you stop and get out of your car. I stepped through a wire fence and walked out into the sage and the new grasses and spring flowers. Before long, I’d come across one of the hidden streams coming down from the Ruby mountains rising just behind me. I stopped and just looked out across the open valley. I almost couldn’t believe the beauty of it all. And now I had friends living just a few miles from there.

Yes, certainly I’d come to Spring Creek to visit. And why not time it for the next Cowboy Poetry Festival?

A Winter Drive

A few miles east of Reno the cold gray sky had come to rest on the ground. The traffic on Interstate 80 had thinned out, but now and then a big rig appeared out of the fog and rolled by. The drivers of the big rigs seemed to see better, or maybe they just didn’t worry about us little folks. A big gray tanker—entirely gray, except its running lights—was gaining on me. It looked like something out of Road Warrior. It crept by in the left lane and slowly disappeared into the fog, one blinking red light persisting for a while before it, too, disappeared.

I found myself leaning over the steering wheel, the better to peer into the limited visibility ahead. My radio and tape player had been stolen a couple of years earlier and I’d decided I’d leave it at that; no automatic distractions except the ones already built in. Like it or not, with the familiar world obscured, a feeling of mystery began to displace the ordinary. An eerie landscape appeared stretching off to the right. At times visibility near the ground opened a little and revealed a sort of mud plain, all stillness, with snakes of standing water disappearing into an unknown world with filtered light reflecting off its surfaces. Perhaps it was an old lake bed. It was impossible to know what lay beyond the gray veil closing off the distance. I pulled over and got out. It was cold. Now and then a big rig would emerge from the fog and roar past, a few feet away. Then after awhile, it was silent again.

Arriving

The drive to Elko from the Bay Area is about eleven hours. I arrived at Jan’s and Andy’s place after dark to a warm welcome. Spring Creek stands at about 5000 feet elevation. I awoke the next morning to light snow falling and an entire landscape of white. Over breakfast, we caught up with each other and then turned to the day ahead. Andy handed me a program for the 21st National Cowboy Poetry Gathering.

As I flipped through the pages, it quickly became clear I’d have to make some choices. Events were ongoing all day at two separate locations - the Elko Convention Center and the Western Folklife Center. There were also events at Great Basin College, Elko Junior High and the Northeastern Nevada Museum.

"What about Bimbo Cheney?” I asked, just to get into the spirit of things. Bimbo was someone Andy had mentioned earlier, one of the friends Jan and Andy had made in Elko during the past year, and a cowboy poet.

“Bimbo already read, but we’re going over to his place tomorrow night for dinner,” Andy says.

I turned back to the schedule of events. There were workshops: Horsehair Hitching, Pulled-Wool Saddle Blankets, a Roping Clinic, Writing and Remembering, Saddle Songs, Dance [Two-Step, Waltz, Pony Swing], Cow-Camp Dutch Oven Cooking, Starting the Young Horse on Cattle, Up Crazy Creek Without a Paddle [Saving Our Sanity Through Communities] and others.

“What’s horsehair hitching?” I asked.

Andy got up from the table and came back with a coil of rope with a handmade look to it. “This is a mecate. It’s braided from horse hair. People make other things from horse hair, too. It’s too bad the hitcher we wanted you to meet isn’t coming.”

I turned back to the schedule. Evening programs. Besides cowboy bands, singers and dancing, there were: Stories from the Fire, Caballeros Sin Frontiers, Cowboy Favorites, Across Cultures, Nighttime in Nevada, Ballads, Laughter is the Best Medicine and Local Roots among others. During the day there were cowboys telling stories, reciting poetry and singing more cowboy songs. There were art exhibits, history lectures, video screenings and panel discussions.

“What do you want to do?” Andy asked.

“Well, first of all, I want to see some of this rawhide braiding I’ve been hearing about,” I said, putting the program down.

Andy disappeared down the hallway. The items he brought back weren’t the products of some remedial pastime, but elegant and well-crafted objects from a part of life I’d simply never seen before. “This is a bosal,” he said. “Sometimes it’s called a hackamore. And here’s a set of romal reins.”

“Are these from the buckaroo tradition?” I asked.

It was back in Sebastopol that I’d heard Andy talking about buckaroos. He'd tried to explain a little about the buckaroo tradition, but I hadn’t been able to get past the cornball associations this word triggered: “Hey buckaroos!” I could hear a TV cowboy saying to a bunch of ten-year-old boys in cowboy hats and packing cap pistols. “Say partner, are you any good with them six-guns you got there? Now be sure to eat your Wheaties and someday you can ride broncos, too, jes’ like Pecos Bill or shorty over thar!”

Buckaroo was a term of benign condescension reserved for kids engaging in cowboy fantasy, wasn’t it? It referenced a bucking horse, didn't it? The rider was, therefore, a “buckaroo.” How could a grown man who called himself a buckaroo be taken seriously?

It was Robert Boyd, the Western History Curator of the High Desert Museum in Bend, Oregon, who set me straight about this term in a lecture he gave the following day, “California Vaquero to High Desert Buckaroo.”

The word "buckaroo" evolved from the Spanish word vaquero. In Spanish, the “v” is pronounced like “b” in English, which yields something like “bahkero” which was Anglicized into “buckaroo.”

Boyd’s lecture was a lucid introduction to this tradition that began far from “our landscape of rimrock and sagebrush,” a tradition which evolved “over seven hundred years and across three continents.” It was traceable all the way back to Arabia, through Spain and Mexico - “and was distinguished by regional customs of horsemanship, language and style of dress.”

Boyd described the buckaroo tradition as “a way of life, a calling, a chosen work.” And what I was about to discover, rather felicitously, in my three days in Elko, was that, unknown to most of us city dwellers, the buckaroo tradition is a way of life that continues even today.

The Festival

The first morning at the festival, as I walked around the foyer in the Convention Center, I soon noticed a group of people surrounding an older man wearing a nametag, Pat Richardson. Had he been doing many festivals? How was it going? etc. Richardson was laconic. Yes, he’d been keeping at it, reading at quite a few festivals. He’d been here; he’d been there. Yes, word had been getting around about him and his poetry. “If it weren’t for that, there’d a been a lot more people coming to hear me.”

His deadpan delivery left me in a moment between laughter and hesitation, wondering if there was a protocol I needed to learn.

So I stood at the edge of the group, listening. Finally, mustering a little courage, I stepped in closer and said, “You must be one of the cowboy poets reading here then.”

“Yes,” he said, looking me, clearly a clueless fellow, square in the eye, “One of the best.” It was said straight-faced and flat-out directly while holding my eye.

But, but, wasn’t that some humorous self-deprecation I heard just a minute ago? I stuttered, inwardly. As the moment stretched out, I suddenly realized that the humor went both ways. Richardson cracked a smile.

The morning programs hadn’t yet begun and there were lots of people milling around in the lobby. I spotted a tall, gray-haired man in earnest conversation with a sturdy older man who, I noticed, was wearing a tag on his shirt. I moved in closer. The tall man was talking about wafers and the Eucharist and how that all related somehow to grass.

I couldn’t believe my ears, and suddenly wished I’d been in on the conversation. It had to do, apparently, with one of the poems of the shorter man. Grass. Communion.

I peeked in at his nametag: Wallace McRae.

Walt Whitman came immediately to mind: Leaves of Grass. Maybe a long shot, I thought, but what the hell? I took a chance with, “I’m going to guess that you both appreciate Walt Whitman, Leaves of Grass.”

McRae turned to me and nodded. “Yes I do,” he said, and now I was included in the conversation.

Already, as I learned later, I’d met two of the most respected of the cowboy poets. And over the next few days, I found the gathering was like that—if you wanted it to be. All you had to do was take the chance of extending yourself.

Since I’d missed the first three or four days, I sat in on only seven or eight scheduled events, all of them a treat, but as far as I was concerned, every aspect of the gathering, formal and informal, was of interest. I found myself marveling, for instance, at the big four-wheel drive pickups in the parking lots, always shiny and well cared for. Invariably, it seemed, when such rigs came to a stop, an older gentleman would step out: ranchers, I estimated.

For them, no doubt, the trucks were essential tools and not merely ornaments of masculine display as is typical of the suburban truck fancier. More than once, I’d noticed a pickup out in a pasture maybe with a few bales of hay stacked in the bed.

The time I spent in the Western Folk Life bar with Andy yielded its moments, too. I took the chance to order a “sarsparilla” (root beer!) and even a couple of bottles of “Buckaroo Brew.” They were sold only during the festival, I was assured. The fact was, though, that the bar was only open during the festival. Thanks to Andy, this is where I made the acquaintance of musicians Cactus Bob and his wife Chris Stevenson.

Somehow Andy had become focused on getting his photo taken with Cactus Bob, who I made out to be a man of droll, if understated, sensibility. There was something about him which set him apart. Was it the hat with the cord sewed along the brim? - and tilted back that way. Yes, I knew there were cowboy artists, singers and poets all around. But maybe a few other artists had snuck in among the cowboys, too.

I made out Cactus Bob to be such, an artist interloper of some sort. And he’d had a few beers, as it wasn’t hard to see. And then every time he took his fiddle out from under his arm and played an air, another drink would be pushed across the bar his way.

As I stood there with Andy and Cactus Bob, it wasn’t long before a woman carrying a guitar appeared from out the throng and came over to join us. I’d spotted her earlier in the Folk Life Center’s bookstore. There was something about her style I couldn’t put my finger on, either. She fit in, and yet stood apart, just like Cactus Bob. It turned out they were married to each other.

Ha!

Andy and Cactus Bob and his wife all lined up and I took some photos. Then thinking I needed an address, in case I published one, I asked for a card. Cactus Bob fished one out: Faux Renwah. Hmmm. It took a few moments to dawn on me: Renoir. “You an artist?” I didn’t really have to ask.

Ranch Culture

I have no relatives who farm or ranch, nor any friends. And so my encounters with people who work the land, who depend on animals and crops for their living, have been infrequent and usually happen when I’m traveling. Perhaps while having breakfast at a country restaurant or walking around some small town, I’ll strike up a conversation, but rarer still is finding myself a dinner guest among ranchers or farmers or cowboy poets. And so as we pulled up the snowy driveway, I couldn’t restrain myself. “Is that Bimbo’s double-wide?” I asked, knowing it would be the only chance I’d ever get to utter such a poetic question.

“It’s not a double-wide,” Andy corrected me, with perhaps a hint of disapproval. “It’s a modular home.”

Warmly welcomed at the door, we made our way inside where seven or eight others were already present. Jan and Andy handed off a big bowl of chili to add to the pot-luck, and soon I was shaking hands with Bimbo Cheney himself.

Introductions all around. That finished, I seemed to be on my own. Mr. Cheney was standing nearby, so I struck up a little with him. Sure enough he had been a working cowboy for many years, but a chance for a position at a big mining operation not far outside of Elko had come his way. Now he drove some behemoth machine around all day. It wasn’t a bad job, he said. In the winter the cab was heated and in the summer, air conditioned. Not cowboy amenities, he pointed out.

Cow-boying in the winter, you rode your chilly butt off in the snow tending cattle, and in the summer you worked all day in the hot sun—all for less money per month than he was now making each week at the mine. No, he said, he wasn’t sorry about it, but maybe he did miss the cow-boying a little now and then. It was a young man’s work.

Somehow I’d imagined Cheney an extroverted character. It was the photo with the mustache that did it. But as I talked with him, I found him on the quiet side, reflective, not a swashbuckling type at all.

On the basis of such slight acquaintance, it would be rash to overestimate my understanding of cowboy culture. It is a manly culture, certainly, but also shot full of feeling, the celebration of which, at times, crosses into sentimentality.

Humor and braggadocio are staples much appreciated when artfully done, but these only cover so much. The people I was meeting, cowboys and ranchers, still led lives in which the connection with nature remained substantially intact. One of the videos I saw that evening captured a couple of days of ranch life deep in winter under conditions none of us city folks ever face.

A hundred miles from any town, with snow thigh deep, cattle were freezing, barn doors were blocked shut by drifts of snow ten feet deep, and firing up a tractor or pickup truck was a major challenge in itself. Animals were lost. The husband had gotten trapped in his pickup out in the snow. His wife had to dig out the tractor, get it running, and drive it through miles of snow to find him.

Two days of ranch life.

It was a harrowing peek into what the direct exposure to nature can entail. But too, there are the joys of spring, the fullness of autumn, the rhythms of the sun and the seasons. For the working cowboy and rancher, all the vicissitudes and pleasures of the land are part of life - the new grasses and flowers as well as the storms and droughts. Dwelling in this way, close to animal life, out under the sky, what are the experiences that come? Isn't the real telling of the deeper moments and passages the stuff of poetry?

It was a pleasant evening at Bimbo Cheney’s place. I talked a little with everyone it seemed. Two were farmers from the Midwest, out for the festival who I talked with for quite awhile. There seemed to be a common language.

Over time, an impression has formed, definite but intangible, which I’ve come to associate with ranchers and farmers, but especially with ranchers. Sensing something of the ethos of ranch life, a nostalgia comes over me - a longing. Could it be buried childhood memories coming close to the surface again? Certainly, growing up, my family lived in various rural settings. Or is it something larger? Something established in the body over millennia?

Whatever it was, in the few days I spent in Elko and Spring Creek, something like it came close quite often, but perhaps never so powerfully as when Andy drove me over to Eddie Brooks’ place to pick up his saddle, which was getting something like a tune-up.

“Eddie’s a well-known saddle maker,” Andy explained. But my mind was on lunch afterwards and then driving out to Lemoyne, a little ranching community right at the foot of the Ruby Mountains. I’d seen the place a few days before under a fresh snowfall and, for an hour, it brought back my childhood in the Appalachians when Christmas was still infused with magic.

But first, I was going to meet a saddle maker.

Spring Creek is an open landscape of sagebrush and juniper with a scattering of single-story ranchers, trailers and various little structures on parcels of a few acres. Fenced corrals behind homes with a horse or two are not uncommon. As we drove toward Brooks’ place, snow flurries were continuing off and on. Heading up through snow on the last stretch, Andy pointed off to the left. “That’s a double-wide,” he said, the saddle-maker’s place.

Walking around to the back, I was careful to step in Andy’s boot tracks to keep the snow out of my shoes.

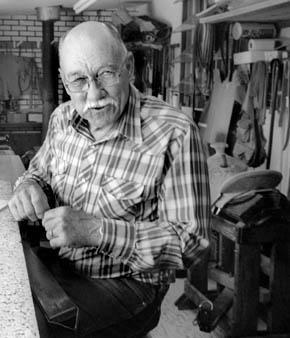

A couple of knocks and the door opened into another world. Yet there was something familiar about it. The workshop was warm and full of the smell of leather. A pot-bellied stove stood at its far end. The immediate impression, I see now in retrospect, was one of intimacy. Pictures and mementos lined the walls along with racks of punches and cutting tools and inventories of leather hanging in strips or stacked and rolled in sheets. A saddle under construction stood on a work stand, and all the unfamiliar implements of the trade stood at hand; a brass spittoon sat well positioned at the edge of a bench.

And I found myself enfolded in the saddle-maker’s world for the time being.

Brooks was a friendly man, mid-seventies, I guessed. He limped. “I got myself a new knee a couple of months ago,” he volunteered and showed us how the leg was now straight. “They were both like this other one before,” he said, pointing and, sure enough, it was bowed like in some old cowboy movie.

Brooks held his head at an angle as he talked, sneaking glances of us and smiling. Meeting strangers was a sensitive affair, and best done without engaging in any rude stares. But he wasn’t reticent and talked happily about his craft. “I wasn’t too smart, and that’s why I’ve been doing this for so many years,” he said glancing up with a wry, conspiratorial smile. Oh, gosh. Hard to resist. I chuckled.

I’d noticed on the back of the saddle under construction there was a number on it, 147. What was that about?

After he’d started working for himself back in 1982, he told me, somewhere along about there, he decided he ought to number each saddle he made. He’d made a lot of saddles working for others, but that’s when he started numbering them. So this one was saddle number one forty seven.

“That’d be about twenty-two years, then,” I said.

“Yes. That’s about right. I’m kinda slow. I make maybe three or four a year now. Used to be I might make seven or eight a year.”

A little later, Andy nudged me and pointed to a little sign up on the wall: “I have two speeds, pretty slow and a whole lot slower.”

Finally I had to ask Brooks what one of his saddles cost.

“That’s kinda hard to say.”

“Okay, let’s just say, what’s the range, more or less?”

“Well, my base price is $2800. That’s just the most basic saddle.”

“What’d you say the other end is, more or less?”

“Well,” he chuckled, “It could just keep going, I guess. I once made a saddle for a gentlemen in Fargo. It had a lot of silver and things on it. He paid me $75,000 for that saddle.”

“Haysoos!”

It was more than the man’s charm that had won me over. It was the experience of being in an atmosphere one no longer encounters today, an atmosphere that arises naturally in the workshop of a craftsman working with hand tools and making objects that are actually needed and put to use.

I remembered years earlier walking along an entire street of furniture makers’ little workshops in Florence, Italy. I didn’t go in. They weren’t retail shops, but the impression remained, of craftsmen working on this human scale.

A saddle made by Eddie Brooks is a labor of love. It's not because it’s old-fashioned. It's because Brooks literally loves his work. It's the natural result of work that is honored and requires skill, personally acquired.

When I’d stepped into that little trailer workshop among the scrub and juniper, I’d found myself, quite by accident, in something like a time warp. I was in an atmosphere where connections of several levels remained intact: the life of the body guided by feeling and intelligence. I’d been utterly unprepared for the quiet joy of simply being there.

In the exhibit at the Western Folk Life Center, among many other examples of the Buckaroo tradition, there had been a display of leather tooling, the designs that leather craftsman use as decorations on belts and saddles and other leather goods. I’d taken a quick look just as I had with silver-smithing and other crafts on display, and I’d quickly passed on to the next thing. All of it stood too far outside my own experience, somehow. But as we stood there talking with Eddie Brooks in that little workshop, I noticed a rectangle of leather perhaps three by seven inches sitting on a workbench. An elaborate design had been worked into it.

“What’s this?” I asked, picking it up.

“Oh, that’s just a sample of some leather I wanted to test out.” he said.

“You made the design here, then?”

“Yes,” he said, almost apologetically. Just a scrap, he seemed to be saying, a trifle. But it was elegant, I thought, as I scrutinized it closely. It was the type of leather tooling I’d passed over so quickly in the exhibit.

“How do you do this?” I asked.

Brooks laid a large piece of flat leather on a work bench under a window where the daylight from the snowy landscape outside flooded in. He reached over to a rack of hand tools and pulled one out. “This is a swivel knife,” he said. Then he took the knife and cut the leather along a curving line. In his hand, it looked as simple as cutting butter.

When I think of how the former California College of Arts and Crafts not so long ago excised the last “C” of CCAC to become the California College of Arts [CCA], I wonder how the thinking went.

Did the decision to remove “Crafts” represent the recognition that the very idea of craft seems to have disappeared? Or was there concern that the mention of “craft” in a primarily fine-art context was a little embarrassing, a little retro, marketing-wise?

Hard to say. How would you sell it today, the idea of craft? “Work long hours to accomplish something that doesn’t seem all that big of a deal?”

I’m reminded of an experience my wife and I had traveling recently. We’d taken back roads coming through Nevada, and then southern Utah, where we stopped for breakfast one morning at the edge of a little town. The parking lot was full of pickup trucks, some pulling horse trailers. Inside, the restaurant was jammed. All the tables and booths were full, but a couple of stools were empty at the counter. We took them. Looking around the room, a lot of cowboy hats were in evidence and, on the wall, I noticed a signed photo of Ronald Reagan.

My wife and I were seated not six feet away from the cook who, with his back to us, was at hard at work. As we sat there, I found myself watching him with growing interest.

Considering the volume of orders, his work space seemed too small: an area of grill-top and four gas burners to the left. There had to be sixty customers, easily—all talking and eating. The waitresses were alert and efficient, and everything was just singing along.

Breakfast orders were clipped to a revolving affair where the cook, who looked to be in his mid-thirties, lean and clean-cut, wearing jeans and a white T-shirt, retrieved each one in order: here was an order of scrambled eggs and bacon. Crack two eggs, peel off three or four strips of bacon, place them on the cook-top, scramble up the eggs with a spatula. Next order: eggs, sunny side up, an order of sausage. Butter a skillet, crack two eggs, drop them in without breaking the yolks. Put some links on the cook-top and a weight to hold them down. Next: two eggs, over easy. Scramble. Flip. Poach. Here’s an omelet. A breakfast steak there. Now some ground chuck. Oil the cook-top. Throw on some hash browns. Work them around. Put the weight on. The scrambled eggs are done. Scoop the bacon on to a plate. Pick up that skillet. Flip the over-easy order. Check the omelet. What about those sunny-side ups?

Six and seven orders were always underway. Each in a different stage of readiness. The cook’s every move was precise, and yet relaxed. Nothing extra. And yet exactly what was needed.

Beside the griddle sat a pitcher of ice water. From time to time, the young man would pour a glass and drink, never losing his self-possession.

My wife and I had ordered pancakes. As I watched our order making its way to the cook's hand, I wondered how was he going to handle the flapjacks. They’d take up the whole grill-top!

And then there it was. The cook read our order and turned to pick up a pitcher. With the same efficient authority as with each other action, he poured one, two, three, four, five, six equal puddles of batter. Set the pitcher down. And turned his attention to the next order.

I watched the batter spreading, spreading, slowing down. Then stopping. Just as the edges of each circle touched. A perfect six-pour! I could barely restrain myself from applauding. But this was no Benihana.

The young man was simply performing his work - work in which there was self-respect. No applause was needed. As I sat there, I felt I was immersed in a culture in which something larger remained intact. Not money or celebrity. Something else was more important.

It was a shame, I thought, that more people couldn’t have seen this young man at work. This was Craft. And beyond that, it was poetry! Yes. I’d go that far. Where does craft end and poetry begin?

I was told that the Elko Gathering, which is now so well known, began quietly as a much smaller gathering of people connected with the ranch life and, somehow, it grew. Even now, 21 years later, when marketing and hype have made inroads, a stranger can still walk up to a famous cowboy poet and have a friendly conversation. That’s what I found.

What is it that’s being celebrated at the Elko Cowboy Poetry Gathering? A way of life, and memories of a way of life. I’m not going to try to make a list.

Back in the Bay Area I found myself reading the one book of cowboy poetry I’d bought, Wallace McRae’s Cowboy Curmudgeon. One of the poems celebrates a camp cook, a provider of nourishment that touched a higher level. McRae writes:

“Both crabbiness and cookin’ he had practiced to an art.”

But although “sour and cynical his vein, did we ever eat!” ∆

About the Author

Richard Whittaker is the founding editor of works & conversations and West Coast editor of Parabola magazine

SUBSCRIBE NOW

TO OUR MONTHLY NEWSLETTER

Share Your Comments and Reflections on this Conversation:

On Jul 1, 2010 Shari wrote:

I see this was written in 2005, but I'm helping a friend of mine look for Ed Brooks Jr., whose dad is this Eddie Brooks. They are friends and she lost contact with him. If there is anyone who might help in locating him, we would surely aprreciate it. Thanks!