Interviewsand Articles

John Toki and Some Reflections on Cultural Service: Richard Whittaker

by Richard Whittaker, Apr 2, 2006

“Why don’t you come to our symposium?” John Toki asked one day when I had dropped in at Leslie Ceramics, a business he owns and manages in West Berkeley. “You can have a table for the magazine.” He was talking about an event at the California College of Art where Toki teaches in the Ceramics Department. The invitation was typical of John’s generosity. Toki and others had arranged a day of slide presentations and hands-on demonstrations by Robert Brady, Lauren Ari, Doug Casebeer and Tony Natsoulas.

Leslie Ceramics, it happens, celebrates its sixtieth anniversary this year. Toki’s parents founded it in 1946. It has become something of a local institution. It's not far from the mark to say that every potter and clay artist within a hundred miles of Berkeley has some useful connection with the place, no doubt an affectionate one. Discovering it myself over thirty years ago remains a fond memory. My interests shifted away from working in clay, but that memory has remained. A long time would pass before I stopped in at 1212 San Pablo Avenue again.

That happened about a year ago, when I realized that w&c #4, which features an interview with Viola Frey, could find a home there. The issue had been in print two years already when I walked in several copies. Hardly had I made it to the counter before a familiar feeling surfaced. Nothing seemed to have changed.

Around the Bay Area, I used take the magazine into bookstores myself. I’ve been met with indifference, rudeness, openness and sometimes with interest. Over the years I’ve made friends with the few bookstore owners and staff who have been willing to listen to someone off the street and look at what they’ve brought in. These small acts of attention can count, certainly for the individual who receives them.

I once had a conversation with John Evans of Diesel Books in Oakland about this, about the part of being a bookstore owner that wasn’t about the bottom line. He talked about cultural service, something he’d thought about a lot. Running a bookstore, he felt, besides being a business, also included a cultural obligation, something intangible, but real. It’s a subtle thing, but one can feel it when this attitude is present in the atmosphere of a place. It disappears as economies of scale take over and customers become the ciphers of a demographic.

I once asked John Toki how his parents conducted the business, what was their attitude about it? He told me his parents had always gone out of their way to make friends with their customers. The relationships that developed were genuine and went far beyond something located in numbers totaled up at the end of the year.

An idea comes back to me that I ran across years ago, that culture is like a web of feelings and values. A cultured person was someone with sensitivity to these things—in him or herself, and in others.

Interactions, transactions—all are grounded in the context of relationship where there's always an invisible element present. When one is met with attention and care, one feels relationship. It's one of the foundation stones of cultural well-being.

I’m reminded of a moment years ago when I was on a solo road trip. I’d pulled off an interstate and into the parking lot of a Wal-Mart. Maybe I needed a toothbrush. Walking in through the automatic door, I stood there trying to figure out which direction to go when suddenly a stranger was standing directly in front of me. “Hello,” he said, with a kind of ritualized clarity.

Startled, I looked at him. A mental case? No. This was someone performing his job, a "greeter.”

It’s intriguing how much can happen in a flash. I recalled reading somewhere that all Wal-Mart stores had greeters. I was hardly ever inside a Wal-Mart and had never seen one. In that microsecond, I felt the both the corporate nature of this human gesture and the appreciation of being helped.

Stepping through the doors of Leslie Ceramics there was no hint of anything corporate. Instead, one feels something of the creative disorder that always seems to go along with living. A variety of announcements, cards, notices and other ephemera always sat on counter tops, or were posted here and there in support of potters and all kinds of artists and craftspeople. And soon one realized there was an art collection on display throughout the store—ceramic pieces the Toki family has collected over the years.

Each piece of art that was on display had a story behind it rooted in some mixture of respect, friendship, support, affection, recognition and encouragement. These are the hidden goods Toki and his parents traded in, goods impossible to measure with price tags.

In the early 1970s, when I was buying clay and glaze materials, I enjoyed the place without knowing the owners or anything about its history. And when I found my way back to Leslie Ceramics recently, it took awhile before I met John Toki himself, who has carried on what his parents began. But one day he was there and introductions were made.

Not long afterwards, Toki invited me to see his studio. He grabbed a piece of paper and began sketching directions. He was moving quickly, but I noticed there was no sense of hurrying. When he handed the sheet of paper over to me, I was struck by how clear the map was.

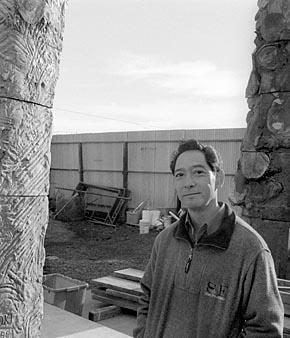

Toki is small of stature, alert and friendly. I think of him as being on the quiet side, but that doesn’t explain how easy it is to talk with him.

I found Toki's studio in an industrial part of Richmond, following a road that turned into a dirt path along railroad tracks. Behind a high fence of funky metal panels, I spotted a large steel crane and several monumental ceramic sculptures rising toward the sky. Struggling with the heavy studio door, I finally managed to swing it open and step inside.

The largest of Toki’s stoneware sculptures stands about twenty-four feet high and weighs over ten tons. It took Toki several years to complete. Another one, now at the Oakland Museum, weighs five and a half tons. They're made in sections, fired and bolted together via engineering of Toki's own devising. Building a crane capable of moving such heavy pieces was a special challenge. “I built everything here!” he told me with a sweep of his hand.

I recognized the note of childlike enthusiasm in his voice. It’s fun to build things, fun to build big things—especially when you have to figure out how to do it yourself! Afterwards, when you’ve overcome all the problems, it’s fun to stand back and look at the simple wonder of what one has accomplished.

Several months later, I asked John what led him to make such large pieces. “To get right down to it, I just like them!" he said. "My dad always used to get on my case about that. He asked why I didn’t make smaller things. The big things weren’t practical, he said. But I just didn’t want smaller things.”

As Toki continued to show me around his studio, I became aware of feeling good; it was contagious. At one point in our conversation, he mentioned, “I own another company, you know. It’s down in Southern California: Lockerbie Manufacturing. They make potter’s wheels and equipment.”

This was a little hard to digest. It must have showed on my face because he added, “I write books, too, you know” and walked over to a bookshelf to pull a couple off to show me.

Someone else might have been bragging, but it didn’t feel that way. He was simply trying to identify himself. I remember noticing the quality of focus in his eyes. Here was someone handling five or six careers at once. How did that work?

The Symposium

Getting back to Toki's invitation, I arrived early in the morning at the ceramics studio at the California College of Art. It was January 21st. The sun had yet to rise over the horizon. The studio door was open and lights were on inside. Somewhere in the building I heard footsteps, and a young woman came around the corner, Crystal Morey, an undergraduate. She pointed me to a table where I could set up. Printed signs were already in place.

I could see student work—greenware, bisqueware and finished pieces—in all directions.. Sculpture was clearly favored over wheel-thrown work. Toki and Arthur Gonzales, the department chair, are both sculptors, but perhaps the lack of pots was simply a sign of the times—the California College of Art used to be the California College of Arts and Crafts. I couldn’t help noticing that fifteen or twenty kick-wheels had been shoved into the shadows against a wall on the far side of the room.

The CCA Ceramics Department fills a large two-story building and includes a gallery, over twenty kilns and extensive studio space with lots of storage and all kinds of equipment for working with clay.

As I was looking around, John arrived. Checking to make sure I was squared away, he headed off with Crystal. There were still things that needed to be done. Coffee and pastries? All set. How about the audio-visual? Check. Enough chairs on hand? Check. Power wheel ready to go? Yes. Raffle tickets? They were ready to go.

Raffle tickets? Leslie Ceramics had donated several hundred pounds of clay plus several sets of glazes and tools. Industrial Minerals Company of Sacramento had also donated materials.

Setting up a public event of this kind always involves more work and planning than meets the eye, but the work had been done and soon people began arriving. And before long, we were underway.

Robert Brady was first up.  In issue #9, I’d published a few images of Brady's work and was especially interested in his slide talk. He took us back to his high school days where his friends, as he joked, were all misfits and troublemakers. It was there he'd had his first experience working with clay. Briefly shown how to roll out slabs of clay, his teacher told Brady “to make a teapot.” That experience was the door that opened into the rest of his life.

In issue #9, I’d published a few images of Brady's work and was especially interested in his slide talk. He took us back to his high school days where his friends, as he joked, were all misfits and troublemakers. It was there he'd had his first experience working with clay. Briefly shown how to roll out slabs of clay, his teacher told Brady “to make a teapot.” That experience was the door that opened into the rest of his life.

As I listened to Brady’s understated and often humorous descriptions, I became aware that something unusual was taking place. It was about sharing something very close to one’s heart. It brought back a question I’ve wondered about before: is there something about people who work with clay that makes them warmer, more human? I even posed this question a few years back on the ClayArts listserve. Here are two excerpts from responses I received: “It could be argued that one aspect of clay working, making vessels to eat and drink out of, builds a strong community. All clay people love using an object that was made by another clay person.” Here's another: “Is there something intrinsic about doing ceramic arts that would support this vitality? We clay people are anchored in mud and warmed by flames—vital? Damned right!”

I was touched by Brady’s generosity. It turned out that the whole day was like that. As I listened to Arthur Gonzales, the department chair, as he introduced each of the four artists, I was struck by the spirit of supportiveness in his own extemporaneous remarks. I already knew this about John, but throughout the day, something similar was coming from each of the four artists in turn. Lauren Ari was so transparently open and free with her artself that I found it a little astonishing. I began to regret that I hadn’t thought to invite friends to this event. This wasn’t what I thought art school was about. Wasn't art school tough, mean-spirited and full of empty, fashionable rhetoric and desperate rivalry? How to explain this? Was it something about working with clay that was causing this lovely, generous atmosphere?

Doug Casebeer’s and Tony Natsoulas’ presentations continued this theme of openness, light-hearted sincerity and sensitive responses to questions, and the day ended with the raffle. Nearly everyone took home something.

I had not been prepared for the genuine sharing and openness that I witnessed. The substance, the underlying quality of feeling so much in evidence that day, is another example of what I’m calling cultural service, but I’d be surprised to hear anyone else using such a term to describe the symposium. The content of the day, in respect to the special qualities of feeling set free in the air, belongs to an invisible realm that we hardly have ways of talking about.

The following day, by chance, I ran into John and his wife, Pam Stempl. I wanted to tell him how the day had been for me. “There was such a…”—I paused looking for the right word. “The whole day was filled with something like,” —I paused again. A word did suggest itself, but maybe there was a more reserved way to put it. No. The word fit. Besides, I’d started a sentence twice already. It was time to finish it: “What I felt yesterday, John, was that there was such an atmosphere of love in the room.”

About the Author

Richard Whittaker is the founding editor of works & conversations and West Coate editor of Parabola magazine.

SUBSCRIBE NOW

TO OUR MONTHLY NEWSLETTER

Share Your Comments and Reflections on this Conversation:

On Apr 8, 2022 unknown art lover wrote:

Very insightful and fulfilling article about an amazing artist, John Toki. Thankful to have. gotten to spend time with his work during my visit to the American Museum of Ceramic art.Especially loved the idea of connecting to this energy beyond time through space and natural resources, the love of his craft and life is extremely evident, raw, and inspiring.