Interviewsand Articles

A Conversation with Hung Liu, : Richard Whittaker and Susie Davis - July 1993

by R. Whittaker S. Davis, Jul 2, 2001

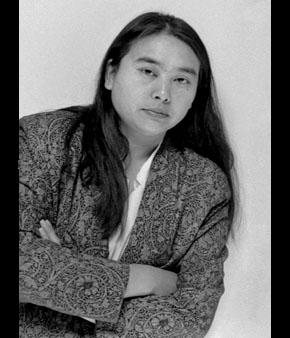

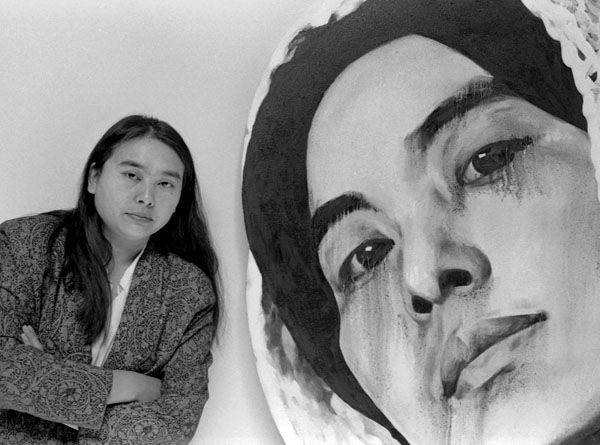

Photos: R. Whittaker

"When we say we're artists and are doing artwork we are already limited and bound by all the rules without knowing it. I remember in China a lot of people still dream of being in the free world - of being artists and doing whatever I want! But the main question is, what do you want to do?" - Hung Liu

Susie Davis, a graduate student at Mills College (and former students of Liu's) and I met with Hung Liu to talk about her art.

Richard Whittaker: You just got back from China. How long were you there?

Hung Liu: I was there for about three weeks. Beijing was where I stayed most of the time. My mom lives there. One thing we did which was unexpectedly fascinating was a family graveyard sweeping ceremony. We went back to my grandparent's hometown. She left when she was five and never came back. In Chinese tradition it is very important to have some kind of ceremony and actually to sweep your ancestor’s tomb every year to show respect. We talked about it, but never did it because of various inconveniences. My grandfather died in 62. My grandmother died in 79. They were finally buried together in the family graveyard in the 80’s.

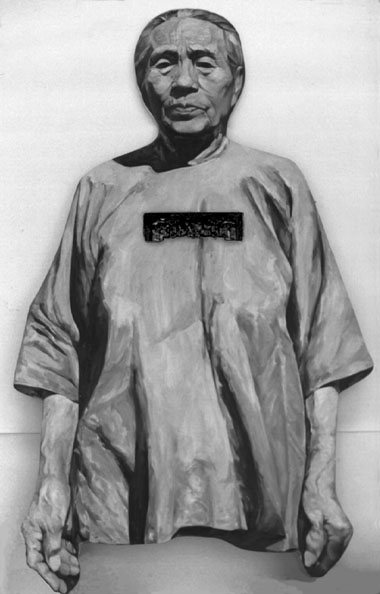

Susie Davis: Is that the grandmother whose portrait you’ve just done?

Liu: Exactly. That's grandma. In the early sixties cremation was still a new idea. But my grandfather said, "That's okay." So after we cremated my grandmother we decided to send their ashes back to her homeland in Manchuria, to Xiao Huang Jin Cun—meaning little golden village, in northeast China.

My mom and I have had the dream of going there to pay homage for years and years, and when I was in China this time she said, ‘Let's do it!’ So we flew to Manchuria. We drove to the village with a lot of relatives, wreaths, and fire-crackers and new tombstones. And I brought my temple money from the U.S., the kind of temple money I found for the first time in Los Angeles Chinatown. This was the first time I used temple money for the use it was made for. I had used it before only in my work. My relatives had the local temple money - blank rice paper, big sheets, yellowish - and I had this fancy Chinatown temple money with gold-leaf and printed images. We burned all the temple money.

There were almost one hundred people involved - four generations. I was very moved by the whole thing.

Davis: I sense in your work that traditional aspects of your culture are important.

Liu: Yes. Being an artist, you're constantly thinking about your work and what can be used for your work - what's the subject matter? the next painting? But I think sometimes we work too hard that way, and we're kind of blind. We don't see a lot of things in life that are actually very meaningful, but don't look like "art." At first, on this recent trip, I was so involved thinking in terms of art, thinking things like "an alter," "shrine," "offering" in terms of doing art. But then I thought, just follow the ritual, maybe I will benefit from doing the real thing. I had used temple money before in my art, but now, well, this was the first time I used it is for what it was made for!

RW: You saw how your preoccupation about art was interfering with living, one could say. And so that could interfere with doing art, too.

Liu: Yes, basically. Maybe it's not that simple, but I feel that when I look at myself or my work I see it in a different context - from all the references from life.

RW: A way of looking at art that interests me is how a person is seeking to find a connection with living.

Liu: I try to express my understanding about what I experience in life. I feel that life is not art. I do think there is a lot more in life—whether you can use if for art or not. But, as an artist, I am the one who may have the kind of magic that can transform the one from the other. So, I think about the shift from Classical art to contemporary art in which the center of focus moved from art to artist.

Davis: What do you think is more important: the end result or the process?

Liu: I think the process is more important than the result. You will have some result. Maybe an object, maybe just some memories. Maybe you just tell stories.. but the process is important. I still want to do good paintings. But it feels liberating that I don't have to worry if I want to do something else, for example, a performance. I can do it.

RW: The marketplace seems to want artists to be defined clearly, but in reality that's often not how it is.

Liu: I think institutions categorize you from day one. In China it’s still like that. In China boundaries are very clear. It's interesting to see how they limit our thinking.

Davis: Was that an adjustment you had to make when you came to the U.S.? Because anything goes here.

Liu: Exactly

Davis: Like in our painting class.

Liu: Especially for beginners. I think it's good to try out everything. If you feed a child just one kind of food he'll never dare to try another. We brought an American Jewish kid with us (to China). When we had my mom's birthday dinner—pretty fancy, a banquet—one dish was fried scorpions!

Davis: Wow!

Liu: The whole scorpion was there. With the claws and the tail, (Gesturing) and I've never seen anything like that in my life! It was a delicacy—very expensive! It was passed around and the Jewish boy who was just before me picked a piece and put it in his mouth. I was thinking, "No, I'm not. It's too much!" But I saw him do it, and I felt obligated. So, I put the scorpion in my mouth, and I think that equals art. You should push yourself to the limit. Try it. It won't kill you. And then you can make a decision. I think it's healthier to open up.

RW: In some Eastern approaches to art making isn’t the real work about a transformation of which the object is the result—and more importantly, the evidence? I guess I'm thinking about Zen here.

HL: Masterpieces are very important in Chinese training. You need to copy, copy, copy. I think this is a way to discipline, a very tight way. You have to follow the tradition. That's the only way you can do it right. But after you have looked at something so long your imagination goes in a different direction. Probably after painting something for the one-hundredth time, it becomes yours.

That’s both good and bad. The inner vision becomes very subtle after so many years of working that way. Later there will be a little change and, wow! This is different from the master! And once in a while somebody did something different. Everyone learned the tradition, had to master it, become a master, and then do something.

Actually that kind of learning environment is almost gone in China. Everything is developing so fast. I cannot believe China is moving so fast. In just two years there's been a big change. New enterprises. There are Yellow Cabs in Beijing! You wouldn't believe it. If you wave anywhere, a taxi stops. China is moving towards Capitalism very, very fast. Scholarship is not as important as making money, and schools are really running down. Now, who cares?

Davis: You tell this story about when you came from China to grad school in San Diego...

Liu: I took a class there from Allan Kaprow in the first or second year. I came from a very classical, conservative country where I had been trained very properly. I had no idea of what his class would be like, but I knew he was famous.

One day he came to the class and said, "Let’s go!" I only knew a few people in the class. We drove to a junkyard and he said, "Let’s unload!" So we unloaded his truck. There were old chairs, bedspreads, just mounds of junk. And he had paint and brushes. Then he said, "Well, let’s do it!"

I thought, "Do what??" I didn't know what to do. I was so scared, I didn't move. Paint and brushes were so familiar, but the setting was so weird! Finally there was a young man and he said, "Okay!"

I think it's because he didn't know much about art that he was the bravest one. He jumped in and poured some paint—very carefully at the beginning. I watched for awhile, then I thought, "Maybe there's no rules!"

Allan’s very smart and sly. He left this ambiguity with you, and you had to ask: "What should I do?" Then you’re just on your own.

Davis: We say we want freedom, but when we’re left with freedom we don't know how to behave because we also want directions. When we think there are no rules and we can set them ourselves, it’s a very scary thing.

Liu: When we say we're artists and are doing artwork we are already limited and bound by all the rules without knowing it. I remember in China a lot of people still dream of being in the free world - of being artists and doing whatever I want! But the main question is, what do you want to do?

When you get here you can do whatever you want, and you don't know exactly what you want to do. So I faced the same thing. "Hey, you’re on your own! The government won't put you in jail." But you're waiting for some kind of advice, or instruction, somebody to tell you what to do. I think that condition doesn't just apply to artists.

Davis: You do a lot of self-portraits. Is that a way of expressing something that needs to come out?

Liu: I have done self-portraits in the past as a way to practice my skill. But the first so-called self portrait I really did in the U.S. is not really a self-portrait. In a classical self-portrait, you stare at yourself in reflection. I did that first one, Fortune Cookie from my green card. It was so clear to me that the intimate, timeless self-portrait from a sentimental age is gone.

Today you carry a lot of other people’s gazes, maybe your parents’, maybe the male-gaze, female, maybe even a governmental-gaze - like that of the green card - all together. And I did a few others, like when I was in the military and also the one on my passport. These involved how somebody else tried to define me.

I wanted to reclaim something: "What do I think about my picture from ten years ago when I was sent to the army?" The latest one is from about 20 years ago. It looks exotic - of some oriental woman. It could be Indian. I think it's beyond myself, not just a self-portrait.

Davis: The first paintings I saw of yours were very emotional for me because you exposed something I’d never seen before, the Chinese women with the foot-binding. Is that something you couldn't do in China and can do now?

Liu. The trigger was the Tiananmen Square massacre. The students were from the art institute where I used to teach. They made that statue, "The Goddess of Freedom." I saw their desire for freedom, and all cultures need symbols for love, for freedom, for justice, and so I thought, "If I were to choose a goddess of liberty what kind of image should I choose?"

I looked at many images and they were all very beautiful, strong women but one night, suddenly, I knew—that's the one I need, because she's crippled, disfigured, she’s in a lot of pain. That's the true condition of freedom in China! I felt I must just project to the world how terrible it is. But her face looks very serene. No emotions. I think the image is shocking. I showed this image at the art commission when I first moved here. The director told me later that there was an older Chinese man who came in. He was offended by the image. He said, "Who did this? We have a lot of great things, landscapes, and so on…" He was trying to deny this.

The government is still patriarchal. I think the Chinese men just hate to admit this history. Women are still not treated equally, but at least their feet are free. Most Chinese scholars of the past were male and they were very intelligent, but they never treated their women with any respect. I think it was Confucius who said, "Only women and little men you don't want to deal with." There was a writer in China who asked, "I wonder if Confucius included his mother?"

Davis: Often if you read the word, "artist" in a publication they mean, "white male artist" If it’s a woman artist or an Afro-American artist they’re often identified that way. Do you classify yourself that way?

Liu: I really don't care that much. I did a piece called Women of Color. I wanted to bring up the irony of this political password today, because who doesn't have color? There are all kinds of women. Even Chinese women don't like each other. I don't want my work to be a kind of one-liner - "Hey, I'm a feminist, woman-of-color!"

It's like a slogan. That’s the kind of propaganda work our government in China wanted us to do. Instead, I want to raise questions, because I don't think I have the answers.

RW: It strikes me that now in the art environment there's a tremendous pressure to politicize everything one way or another.

Liu: If you really don't care that much about that issue, then you better not do it. You may do a neat piece, but the voice is not yours. Bottom line, you can have all this analysis, understanding, knowledge and experience, but overall I think your heart should be there. It's not sentimental, you know. You have to have your heart, and then you can find your voice. If you find your voice people will sense a resonance in your work.

RW: But in today’s art, does the heart have a home anywhere?

Liu: There were several Russian artists who were my generation’s heroes. They went off into the countryside the whole summer and worked every day, painting, painting. I think that kind of life is long gone. The reality today is that it's a quick, changing world. So many things are going on. But still, overall you have to anchor yourself. I still believe in my paintings. I still want to do my painting stroke by stroke. I still want to find some truth through the process. It's not simple. The good thing about being an artist is that I can use my work to transform something - to reach, so I can raise the question, what is this all about?

Several people at different times have told me, "Your work, your paintings, are very well done, very beautiful, but sometimes the content is so horrible. So painful. But the way you paint is very beautiful." It is contradictory.

Davis: Yes. There’s a lot of polarity..

Liu: Right. And sometimes one issue is stronger than the other one, but I just think it's harder than ever. The changing landscape of our world, the hardship of making a living, high tech, computer, mass media—you can see in China the same thing, there are beepers everywhere. Anything in the world you can name has two sides.

RW: Who is with you when you paint? Are you also painting for people in China? For people here?

Liu: It changes all the time. When I was painting my grandmother, I knew I was going to her grave and I had a lot of emotion. I lived with her until I was thirty something. She was an anonymous Chinese woman, a nobody. But in my work she was somehow transformed into an earthy goddess, an anonymous power. When I was doing that I felt she was with me, and also a lot of other anonymous women—not just Chinese women—but every working class woman who raises a family and then just quietly disappears from the world.

I think, in a way, I was doing a kind of tombstone for anonymous working women. She died when she was 90. I remember when she died she only saw black and white TV. She never heard about a washer-dryer. When she was younger she made shoes for everybody. Later we abandoned all those home-made shoes. And so I was thinking about the changes, the big changes, even in my own life time.

When I was little our house was next to a train station. In America the railroad-buffalo age is long gone. So I came from an age like your buffalo age. No television. Radio was even very rare. Then quickly to black/white television to washer, dryer, refrigerator. These changes are all within me. I have really experienced all this. So all this is a pretty heavy load, and one way or another it will come out in my work.

About the Author

At the time of the interview Susie Davis was a grad student at Mills College who had studied with Hung Liu. Richard Whittaker is the founding editor of works & conversations and West Coast editor of Parabola magazine

SUBSCRIBE NOW

TO OUR MONTHLY NEWSLETTER

Share Your Comments and Reflections on this Conversation:

On Oct 10, 2021 Lorraine Carribean wrote:

My Grandmother was quilter, but the materials she used weren't of a lasting quality, lye soap was no doubt not the best to use - little still remains intact...my Son has asked me to make him a quilt... with and I have come up with a huge number of reasons the project is not possible...The quilting rails, cutting of hundreds of pieces of patch work, and hundreds of hours sitting at the quilting Now I am considering the freedom I have had in my life as compared to Liu and her grandparents. I am going to make that quilt!On Oct 10, 2021 fred wrote:

she is incredible !!! art warriorOn Oct 10, 2021 Kristin Pedemonti wrote:

What struck me was to fully remember and honor the process and not get so caught up in the outcome, the piece created. Perhaps this is because of my immediate context of final phase of my Innovation Project for my Master's in Narrative Therapy and Community Work. I am melding the metaphors and hands in practice of Kintsugi with Narrative Practices. It's been profound to witness survivors of abuse slowly open to the idea they are not the 'single story ' of'forever damaged,' they are so much more, so many skills and abilities were used to survive their abuse. We celebrate this and honor their scars through this process. I look forward to continuing this work and I thank you for the reminder to know the process is valuable too. ♡