Interviewsand Articles

Toward an Ageless Society

by Mary B. Moorhead, Apr 2, 2006

This is the second article about Eldergivers, a San Francisco nonprofit organization with a mission of fostering a positive connection between elders and the community.

Collaborating with the fine arts museums of San Francisco and Bay Area arts schools, Eldergivers established Elder Arts Celebrations (EAC) in 1999. EAC annually exhibits the visual arts of alumni, faculty and students over age 65, who have attended such schools as CCA, SF State, SF Art Institute and City College. EAC negotiates juried exhibitions at well-respected venues like the de Rosa Reserve, California College for the Arts, and San Francisco’s de Young Museum. EAC works closely with the SF Arts Commission in choosing the annual jurors.

Mary B. Moorhead is an elder care consultant and family counselor.

The program

Although my daily work involves elders, and my hobbies include the visual arts, unbelievably, I knew little about ELDERGIVERS programs until I attended the 2005 EAC exhibition that was part of the de Young Museum’s grand opening this past October. Not sure what to expect, I parked my car and entered the Museum’s lower galleries. Before the doors even closed, I found myself in a packed crowd of all ages, standing shoulder to shoulder, delighting in the watercolors, paintings, and mixed media works on display by EAC artists.

Across a room, Orr Marshall’s large painting Graffiti Girl grabbed me. Moving closer, I was riveted by this contemporary image. And truth be told, although my personal belief system shouts, “Yes, elders can do anything,” I admit a mild shock of surprise that an elder, non-celebrity artist would create an image so in sync with contemporary urban culture.Viewing piece after piece, I decided this exhibit was indeed worthy of a major museum like the de Young. I could easily imagine the show traveling to museums across the country. It struck me that if a specialist on aging could be surprised by the caliber of art, then many others would be too.

In preparation for this article, I created a list of questions for the artists and ended up speaking with Orr Marshall, Michael Grbich and Violet Chew-MacLean. But first I met EAC Director, art instructor and artist Mark Campbell.

We got together on a sunny December day at an outdoor cafe in SF, and my questions were quickly abandoned as we launched into a swift, wide-ranging conversation. Campbell explained that EAC actually grew out of another program, Art With Elders (AWE), where art instruction is offered to skilled nursing home residents, and later the work is exhibited. It was an epiphany to everyone, he told me, that frail, and sometimes ill, elders can produce art of such a striking quality. “As we developed the EAC program, it became very clear that elder artists project their gifts actively and repeatedly and, when given the chance to view elder artists’ artworks, the public is enthusiastic! What’s more, public responses to the shows confirmed our original hunches that art can be a powerful tool to counter negative societal attitudes about aging. If people could just realize that we have the capacity to do many things at any age,” he said. “Look at Michael Grbich. Not only is he an active artist, but he also has more energy than many thirty-five-year-olds I know. Grbich is seventy-five and learning tightrope walking, and he’s been tap dancing for years!”

Later Campbell pointed out that unfortunately, but not surprisingly, EAC needs funding to continue. Immediately my fantasy of a traveling show evaporated. Where would the money come from? It’s an ongoing question.

The artists

Orr Marshall told me about an EAC planning meeting at SF Public Library in October of 2005, “Connected with the topic of promoting EAC and the work of elder artists, we discussed ageism, the discrimination against elders because of their age. Some of the points made by speakers at the Elder Arts reception at the de Young are helpful. Didn’t Wayne Thiebaud say that, in contrast to sports, with the visual arts, it doesn’t matter how old you are. Theibaud adduced some famous examples, such as Picasso.” [What about Thiebaud himself? I thought.] “To my mind,” said Marshall, “comes the Japanese printmaker and painter Hokusai (1760~1849), who called himself ‘The Old Man Mad about Drawing.’ At quite an advanced age he said he’d finally learned how to draw!”

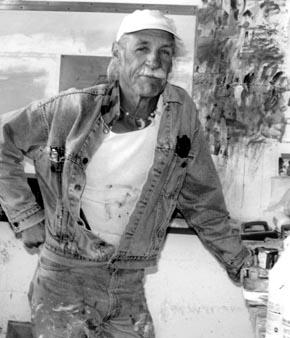

Michael Grbich, lanky and well muscled in running shorts and a baseball cap, appears permanently poised to run a marathon. He absolutely does not appear to be seventy-five. He has so many interests, I could hardly keep track. Awhile back, between 1959-1979, he collaborated with family and friends and built his house from collected building materials including salvaged timbers and fir flooring from the Treasure Island Navy Barracks.Speaking about painting, Grbich says, “For me, the act of painting is similar to an electrocardiogram of my deepest feelings and these feelings are primordial, mysterious and inexplicable.” Grbich’s abstract paintings are comprised of an eclectic choice of materials. For instance, acrylics, metal and mirrors make up Tina’s Mirage. I Risk, Therefore I Am interchanges metal and acrylics in a gridlike pattern.

Violet Chew-Maclean radiates gentle steady power, intelligence and creativity. We met at her Concord home. Her spirit and sparkling brown eyes belie the fact that she is waging a forceful battle with cancer. Dressed in an elegant, fitted brown wool dress, she showed me three watercolors portraits of children, that show off her drawing skills. As we settled on a couch to chat, she explained that her personal and artistic values center on “the mind, spirit and body.” Chew-Maclean is a long time, active artist who earned an MFA in Figure Painting in 1964 from CCAC.

Violet Chew-Maclean radiates gentle steady power, intelligence and creativity. We met at her Concord home. Her spirit and sparkling brown eyes belie the fact that she is waging a forceful battle with cancer. Dressed in an elegant, fitted brown wool dress, she showed me three watercolors portraits of children, that show off her drawing skills. As we settled on a couch to chat, she explained that her personal and artistic values center on “the mind, spirit and body.” Chew-Maclean is a long time, active artist who earned an MFA in Figure Painting in 1964 from CCAC.

Conversations

Moorhead: As an older artist, is it difficult to find venues to exhibit, or to attract interest in your work? Are galleries less interested in your work?

Marshall: I have been an artist all my life, and I have always run into the same problem with galleries, namely, that I can’t satisfy their usual requirement for mass production of artwork. Most galleries will ask artists to show them slides of 20 to 40 works done within the past year, and those works should all be similar variations on a single theme. If you look at a number of my works, you might understand that they take a long time to do, anywhere from several months to several years, and you’ll see quite a range of themes and styles. Graffiti Girl took almost 2 years to paint.Grbich: Yes, society emphasizes youth, hormones and now makeovers! Which is too bad because no one gets out alive. I taught art for 30 years to Miramonte High school kids and was a teaching instructor with the University of California Berkeley Summer workshops. I learned so much teaching, but I had less time for my own artwork. Now I have time, but it is not so easy to find venues for showing.

Chew-Maclean: Actually I’ve had several requests for shows, even one retrospective. But I was ill at the time and didn’t have the energy. It was a huge help when EAC handled all the details of exhibiting my work.

Moorhead: How do you feel about the EAC? What has the experience been like?”

Marshall: My experience is successful. Elder Arts Celebrations performs an outstanding service for artists like myself who have been so fortunate to exhibit with them. I had no idea whether there was any hope of my work being accepted by Elder Arts Celebrations for their Fall 2005 show in San Francisco, or whether I was even qualified to apply. I do not teach now, but taught at the California College of Arts and Crafts (as it was called then) from 1961-68, at the school’s original Oakland campus. But I applied anyway, and I was amazed that Graffiti Girl was accepted not only for the San Francisco campus exhibition at California College of the Arts, but also for de Young Museum opening exhibition.

For a person like me, living in Eureka, California, who has had poor luck in being accepted for juried shows, it was a huge boost of encouragement to be shown in both places and to receive so many positive reactions to my painting, even from some of the de Young museum guards. During the de Young reception, a young couple told me they wanted to buy it. The couple had recently taken a trip to Japan and they thought my painting perfectly conveyed the modern spirit of the country.

One of the most heart-warming comments I heard was at the end of the very last day of exhibition. As visitors were being hurried out at closing time, I saw a little girl perhaps 10 years old standing in front of my painting and photographing it with her cell phone. I said it was my painting, and she replied, “You did that? It’s sooo cool!”

Grbich: EAC has been a wonderful, very positive experience for me. I would not have exhibited in such well-respected venues like the de Young or the de Rosa Preserve or California College of Arts without EAC sponsorship.

Chew-Maclean: EAC is a wonderful organization, especially for those who paint and paint, but cannot find places to share their work. Also, it is great to just be ourselves without any requirement to be glitzy in some way to market our works. We can just be darn good elder artists who have been drawing or painting for a long time.

Moorhead: Do you feel that the visual arts can act as a catalyst to change the general cultural view that elders have little to offer society?

Marshall: If it is widely publicized and seen by enough people, I think the work of older artists can combat these prejudices and contradict possible expectations that our work might be dull and conservative. It is very important to exhibit our art and make it better known, especially for artists like me who have had relatively little exposure.

Grbich: Yes! Role models change society’s expectations. I read the obituaries daily, just to see what people have done with their lives. There was one lady who lived to 94 and walked miles a day until the end. And Kitty Carlisle was just in the news. She’s 95 and still practices singing a half hour daily! This is a great boost to me. If she can do this then I can, too. I think nothing is impossible.

I learned this, too, as a high school teacher, that aging is a state of mind. Some of the students were already old. If you choose to be old—to think and act old—well, you are what you think.

Chew-Maclean: Yes, we can change US cultural views, but it will take some work. You know in China that elders are respected and revered; not so here in America. Here elders are throwaway people. The public will have to reawaken to the gifts that older people and older artists possess and reveal. This will take publicity and very good writing. Elder Arts Celebrations is very important in this way.

Moorhead: Do you feel that, as an older artist, you have something unique to offer society?

Marshall: As distinguished from some other careers, I would say it is sometimes possible for an artist to continue a creative working career until the very end of life. Over those many years, the artist can develop a degree of skill, clarity of vision and strength of purpose that result in work of special insight and value to the public in general, and to other artists in particular.

Grbich: Yes, and people who have something to do, to accomplish—an art career, or other interests—live longer, I think. As I said, I look for role models and I hope I can be a role model for others. If we can show others how active and engaged we are, that is role-modeling. I love my tap dancing lessons, still play tennis and am a senior Olympic runner. I am practicing to become a funambulist—great word isn’t it? I ordered this tightrope walking apparatus from France. It is set up in my living room. As I practice I try to find my balance, and life is all about balance isn’t it? We are all walking a narrow rope in life anyway, right? And we need to become comfortable falling too, yes?”

Chew-Maclean: Oh, yes. Artists have so much to offer the public, to open their eyes. The great thing about all the arts, really, is that the more you grow, the more your art matures. You attract more people to your work. They may not know philosophically why they like your work, but they do. All my life I have based my artwork on values that emphasize the spirit, the mind and the body. I taught this to high school students, too. So this is all something to offer society.

In the October meeting we discussed different tiles for EAC, looking for alternatives to the word ‘Elder,” only because there is so much prejudice just around the word! But why should people be afraid of the word? Long lives, experience, accumulated knowledge and wisdom are important in China. Elders are revered, and if you are old and frail, they take wonderful loving care of you.

Moorhead: How does being an older artist compare with being a younger artist just starting out, say in their 20s or 30s, or a mid-career artist?

Marshall: As a young art student and on into my early 20s, I wasn’t sure what I wanted to do with my art. In my 20s I had an inkling of what I wanted to do, but I didn’t know how. Through my 20s, 30s and 40s I was developing my skill and sharpening my focus, but because of teaching in art school and college (and with family responsibilities), I didn’t have enough time. Since then, I have discovered exactly what I want to do. I know how to do it, and I have the time (although there’s never quite enough), so right now is the best time of all.

Grbich: Yes. Just living a long life offers experiences that mature us and enter into artwork. I will never regret my years of teaching art to high school kids. I learned so much from teaching, and I have many contacts with my former students that enrich my life now. Also I’ve had tragedies, my wife died. I lost a house in the fire. These experiences changed my work and me. Setbacks invite you to look at life, give you experience to draw on. Older people are like time capsules, with all this stored knowledge and experience.

Chew-Maclean: My art never stops growing. I surprise myself! Sometimes, I wake up and look at my work and wonder, “Did I do that?” Artists continue to grow; there is no end to it. My mother was born in China and I was born here. She had typical ideas about girls, that I should be a secretary. But I actually attended art school from age 9 to 16. I had a mentor. Dolores Gardiner, who kept track of me, encouraged me and even helped me win scholarships to art school. We stayed friends until she died at 94.

I encountered prejudices against Asians, women, and artists all my life. Growing up, everything was for men, it seemed. I know many artists who are now famous; most of them are men. Some of them could not draw! One borrowed my figure drawings, all in color, for quite awhile. My Chinese background, my values and my use of composition affect the way I compose the figure. After that, his work changed because he copied my composition style! But no matter. I kept to myself, doing my art, kept going. Personally and artistically, I stuck to my own values.

Actually I am lucky to have a Chinese background. Chinese calligraphy is all about metaphors, which I understand well. I taught metaphors to high school students. If children are taught metaphors, they start growing much faster. My students learned so much faster than their peers; many went on to become successful artists.

It does not matter where you travel. The metaphors are the same. X is the metaphor for conflict. If you look at Hieronymus Bosch, he painted hell and heaven. All that was hell was an “x.” Vertical stands for stability while horizontal indicates peacefulness. I would ask the students “when you stand up how do you feel?” “I feel stable,” they answered. Then I asked, “How do you feel while you are lying down? “Peaceful and restful,” they answered.

This country is becoming more and more multicultural, and metaphors are multicultural.

Moorhead: Does the creation of art give your life purpose that defies aging?

Marshall: As an older artist, my principal concern is with internal factors rather than external acceptance. To be specific, at my age—I’ll be 69 this year—I wonder how many creative and productive years are left to me—perhaps ten, hopefully longer, but possibly even fewer. Considering the long time it takes me to produce a single work, will I be able to fulfill my potential, to bring forth the many works that are now only ideas or dreams?

Some of the greatest artists have produced a flood of masterpieces in an amazingly brief burst of creativity and have died young; some have poured out a steady stream of great works throughout long lives; and some have developed gradually, to reach their full powers later in life. I consider myself to be of the final type, a “late bloomer”—and I hope not too late. Thus I feel a strong pressure to concentrate as intensively as possible on my art. It keeps me constantly alert and mentally engaged and challenged, and a friend reminded me of the little-known secret about artists—they don’t get old.

Grbich: Yes. Having few interests, and no passions, can kill you. Passion is what keeps you going in life, and art is about passion. Talent is a gift, but this alone doesn’t make you successful. Hard work and passion are what turns talent into art. Some days you are tired or can’t perform well, but passion keeps you going. And it all means nothing unless you have something to say.

Chew-Maclean: Oh, yes. I have cancer; I was really sick but feel stronger now. So my body is ill, but my mind and spirit are very strong. In America youth dominates. Advertising dominates, too. The US culture follows the money. Maybe it will change with all the baby boomers getting older!

Elder artists need to show their work more—and leave the word elder in it! It is not wrong. I told the group, you just feel like it is wrong. Don’t look at “elder” as a dirty word. EAC can help here. You know, once you see the truth, you never forget it. But you have to keep looking for it. Then the truth grows with you.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

I have a fantasy: We will turn our culture upside down. Elders and young folks would change places. Elders would be honored and looked to for leadership in all facets of life. Elders would be sought after in business, the arts, even in Hollywood. If this is too tall an order, perhaps we could aim for an ageless society, where we all learn to respect and rejoice in each other’s gifts, no matter our chronological age. EAC makes the point, that art is ageless—but for people to realize this, the artwork of older artists must be seen. —MM

About the Author

Mary B. Moorhead is an elder care consultant and family counselor.

SUBSCRIBE NOW

TO OUR MONTHLY NEWSLETTER

Share Your Comments and Reflections on this Conversation: