Interviewsand Articles

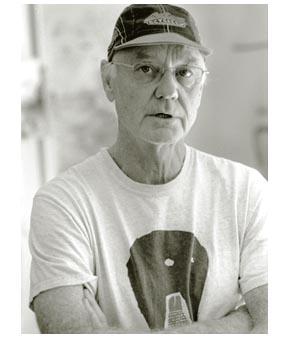

Interview: Robert Brady: Desert Canto

by Richard Whittaker, Apr 2, 2007

Robert Brady is an accomplished potter. His history of making pottery goes back to his high school days, but his work long ago expanded beyond the traditional territory of the potter. Exploring a wide range of forms from small to very large pieces, he became established as a major West Coast artist working in clay. Then he began exploring wood as a sculptural medium. For many years now Brady has worked in a number of media, turning out a prolific body of work, always with his particular eloquence which frequently seems to embody ancient, archetypal qualities. We talked at some length about the artist’s early life, his love of the desert and some important early experiences.

Richard Whittaker: I enjoyed your talk at CCA [California College of Art] and wanted to hear more about your high school experiences. You said you ran around with some miscreant youth.

Robert Brady: [laughs] Well, I was playing that up a little bit. I was actually generally accepted by the cool crowd, the popular kids, but I tended to run around on a daily basis with kids who maybe weren’t in that crowd. The picture I showed in the lecture of the ceramic club that I started had in it one guy who was a golden gloves boxer who came very close to going to the Olympics. He was from a background very much like mine. Divorced mother. Single parent and middle to lower middle class. Next to him was a guy who was just kind of a goof, Lloyd Brethauer. I liked him a lot and ran around with him. Next door to me there was a guy who built Ascot speedsters.

RW: Were you into all that, the car thing?

RB: I know quite a bit about engines being a product of the fifties. My brother, who was older than me, was building an engine to put in a car to take to the drag strip, and my dad was a car salesman. He was quite a few things. He was basically tied to the gambling industry in Nevada, but when he would get dissatisfied with the business, he would pull out for a few years at a time. He was a car salesman when I was young. Before my parents got divorced, I can remember, my dad sold Lincolns and Mercurys, and he would pull into the driveway with any one of those cars on a daily basis and say, “Hey, jump in. We’ll go for a ride!”

I was five, or maybe six. I do remember that so well. If he ever got a little dissatisfied with a car, he’d just get rid of it and get something else. He owned a very hot-rodded up 1957 Buick at one point. Later on he had a Corvette with the biggest engine. I used to borrow that, so I feel like I grew up in a time when car culture and motorcycle culture was in the air. It definitely was in my family, and to this day, I love things with wheels on them—bicycles, motorcycles, cars.

RW: That’s evocative for me, too. I remember the mystique, the attraction of cars.

RB: Where did you grow up?

RW: I was a teenager out east of LA.

RB: I also lived in LA from 1957 to 1960. LA is still the fashion capital of just about everything, but surely cars are revered more in Southern California than maybe anywhere else.

RW: Do you remember looking at cars and having special feelings about the way some of them looked? I can remember my own examples of that.

RB: Well first I’m going to guess about the American relationship with the vehicle—that it represents freedom, going anywhere you want, roaming about. You can get out and drive a hundred all day long across Nevada.

But I remember that my friend and I would have this game. We’d ride our Hondas around and stop at this place where you could get 19-cent burgers. We’d sit there and take turns identifying every car that would come by, “’53 Chevy.” I still find it pretty interesting to look at the designs of these cars from the point of view that it’s somebody’s idea of good design.

RW: I can remember, for instance, that I loved the ’53 Lincoln, especially the design of the rear fender and the tail light on that model. I could dwell on such things.

RB: I remember the ’53 Lincoln. It had a tail light that came down like this [gestures].

RW: That’s right. And I remember the amount of feeling I invested in these things and in certain color combinations, too. Do you connect with that at all?

RB: Well, yes. So what’s that feeling? How do you express that feeling?

RW: I think it’s a deep thing, actually. How I express it, I don’t know, but I still see this sometimes with a certain combination of colors. For instance, in that small space before anything closes in, there’s that same feeling I’d feel when I was seven or eight years old, or even younger…

RB: So it recalls an earlier response to something.

RW: Yes.

RB: What I do now when I look at cars or motorcycles, or even bicycles, is make a judgment in terms of form and shape and design. I find it interesting how the same body with a different color and slightly different tires, can be pretty damn right, but the same car with the wrong color combinations and funny wheels can just be out of balance. When it’s really right, I savor its design balance. I tend to just admire it for its overall integrity and beauty. But still, that’s not answering the question of what it represents exactly.

But vehicles, first of all, they’re forms of transportation. Then, besides just the functional aspect, it begins to allow freedom of movement, and that leads to experience you couldn’t have otherwise. So I think naturally that all vehicles, universally, trigger that response, whether it’s conscious or unconscious.

RW: So vehicles, on a conscious or unconscious level, point in the direction of freedom.

RB: And escape. [laughs] You get the hell out of here, in more ways than one! Yes.

RW: Escape. Maybe that’s even more powerful. How do both of those things resonate for you?

RB: When I was young I could not wait to get a motorized vehicle. When I was living in Los Angeles, and was too young, I’d look in the back of Popular Mechanics. They’d have these little scooters with these little four-stroke Briggs and Stratton engines. At thirteen and a half, I talked my mom into letting me buy one and just have it in the garage, but when she wasn’t looking, I was riding it. And there’s a certain kind of elixir in the feeling of riding and the slight risk, or the speed factor.

RW: Experiences on the Honda?

RB: Or with a car. If I step on the gas and run that car up to 95 for a few seconds, my hands get a little sweaty. It’s a little bit of a thrill. Part of that is not wanting to get caught by a cop, and if you don’t, it’s kind of a rush. In a sense, I guess, that’s an escape from a more static condition that we normally experience.

RW: I wanted to go back to how sometimes a car or bicycle might have just the right design. You said you would savor that. Could you say anything more about that savoring?

RB: It’s not unlike looking at anything that is pleasurable to look at, including art, fine art. I would look at it like many other things, a good pot, a sculpture, possibly a painting.

RW: You’d get a feeling there?

RB: Yes. Although, I guess it’s different knowing that there are maybe a hundred thousand of that same vehicle out there. When I see one—whether it’s a car, a motorcycle or even a bicycle—that’s aesthetically balanced and well designed, it makes for a total appreciation. It’s just like, yeahhhh… I love that! I guess I don’t want to try to contrive a greater philosophical slash emotional explanation of what I’m getting from it than that.

RW: Well, I mean, artists say—and with justification—“If I could put this in words, I wouldn’t have to make the art.”

RB: Well, it’s a little bit why one artwork can completely stop us in our tracks. I mean, I saw a pot one time in the Philadelphia Museum. I was going to give a talk there that night, and I had the day free. I started at the bottom and just worked my way up through every floor. I saw a lot of good things—Brancusis, Martin Puryears, there was a whole room of Shaker stuff. Beautiful! I love the reductive, depersonalized quality in that work; there is no extraneous design, or anything like that.

So I had looked at all that, and I got to the top floor and finally walked toward the elevator to leave. I walked past this little vitrine right by the elevator. In it was a little pot about this big [gestures]. I stopped and looked at it, and this pot just gave me this flutter in my chest. I’m looking this thing and thinking, How can it be that this little object here can compete and rise above everything else I’ve seen in this museum? It was about seven hundred years old.

I love Japanese pottery, but this pot didn’t remind me of anything, quite. So I kept looking at it. Then I began wondering, how did these people back then know how to make a form that had so much power? That caused me to start thinking about how did form come about, period? How did the Greeks arrive at the amphora shape? In the end I could only guess a little bit, but I still couldn’t really explain what it was about this pot that made it so incredible.

RW: That is a very interesting moment you’re describing.

RB: I’ve had a few of those, very few.

RW: Tell me about the other ones.

RB: The funny thing is that they all relate to clay and, more often than not, to a vessel form. There was a show at the Oakland Museum about twenty-five years ago, the Johnson’s Wax collection. It had one piece from everybody in ceramics who was supposedly anybody in the country.

RB: The funny thing is that they all relate to clay and, more often than not, to a vessel form. There was a show at the Oakland Museum about twenty-five years ago, the Johnson’s Wax collection. It had one piece from everybody in ceramics who was supposedly anybody in the country.

I go through the whole show. There were some funny ceramics here and some interesting ones there. There was a big Arneson wall that was really ambitious. I also get to the very end of that little trek, and I’m getting ready to go up the stairway when I notice two little covered jars, the same size basically, sitting next to each other, both similar but subtly different. Both were made by Byron Temple, a very well-known functional potter who died about five years ago. He was an old friend of Sandy’s (Brady’s wife, potter Sandy Simon).

Those two pots just spoke to me in a way that was so powerful. They blew everything else away! And I’m going, “I don’t get it.” How can this pot, which is meant to hold some sugar, or something, compete with that wall over there of Arneson’s? That says something about me, and my love of pottery and the archetypal qualities of function, and that beauty a lot of people don’t regard as highly.

Then another experience was when the Abstract Expressionist Ceramics show was at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art in about 1965 or 66. I went through that whole show and it was a Peter Voulkos piece that just had a profound hit on me. The power and authority of his ceramics is really extraordinary. So those were unforgettable, they almost border on the religious experience or some very powerful things that have happened to me in nature, unexpectedly.

RW: You remember these moments even today, forty years later. So how do these two little pots overtake this incredible wall by Arneson, as you say?

RB: It really isn’t unlike… One time I was driving from Needles, California. We started out on a day like this, pure blue sky, probably 80 degrees at six in the morning. By the time we got to Las Vegas, a windstorm was starting up. We could see only a block or two ahead of us, then it got worse and worse as we headed north out of Las Vegas. My car couldn’t go more than thirty miles an hour with everything it had! Then that finally lifted. As we were approaching Tonopah, a long sloping climb, it started snowing! I mean from a beautiful clear blue sky in the morning, to blinding dust storms, and now we had snow coming down and sticking to road signs and all the sagebrush. I said, “I can’t believe this!” And going up this long hill, there’s mayhem!—cars spun out in crazy positions! I had quite a bit of experience driving in the snow, and I had these kids with me, in a front-wheel drive Renault. So I said, “You’ll have to jump out when I say and push the car!” If the car stopped we’d never get going again. I’d say, “Now!” and they’d jump out at three miles an hour and push! I wove, slipping around between all these cars scattered helter-skelter and, finally I said, “Okay, jump in!” and we pulled away. That was just a great experience!

So we go further, and now the snowstorm is over. Now we’re just driving through the Nevada desert, and there are giant cumulous clouds! Just fucking amazing clouds! And there are big showers just dancing across the desert floor. I’m driving along and, all of the sudden, I just got this overwhelming connection with nature.

For me, it was a religious experience, a connection to the profundity of what this world is, and our experience in it. That’s not really different from what I felt when I saw those pieces. It really isn’t. It almost wants to make you cry from a certain kind of joy, and a certain kind of gratitude.

RW: Your story reminds me of once when I was driving alone in the desert. A lot of snow had fallen and everything was white, except where the rocks were bare. The clouds were all breaking up, some sitting right on the ground and up on the ridges. Sunlight was breaking through and scattering light around. It was atmospheric and ephemeral. At one point there was simply a configuration of all this more beautiful than anything I’d ever seen in my life. I really thought, this must be what heaven is like.

RB: And it took you.

RW: It touched me in a way hard to describe, and it only lasted for about five minutes. You would know something about this.

RB: Yes. I do know. And it’s kind of curious because I oftentimes have thought about this. I mean, sure it was beautiful out there, but I’ve been in so many extraordinary different geographies and places that could engender the same kind of experience, but not have it. I’m guessing there’s more involved. It’s almost like we’re always waiting, consciously or unconsciously. We need that, but you can’t make that happen, necessarily.

RW: Clearly not.

RB: Just to say a little more about that. I find the desert to be much more powerful in an essential kind of way than any other nature situation. I’ve noticed that I can be by the seashore and can be witnessing one of the greatest parts of our universe, the power of the ocean and all that. I’ve been in the most beautiful, sublime Alpine meadows and babbling brooks and shimmering leaves and sunlight and deer and whatever, But the desert… I mean, we have sagebrush out there, little animals, a lot of nocturnal animals, foxes, coyotes, so certainly it’s a living landscape. But it seems like the artifice and the frills and the dressing has eroded and cannot exist there. So there is more of the bearing of the fundamental, geological soul of this universe there. It’s like the Truth, you know? And the desert, no one has attempted to “fix” it, except in communities like Phoenix and so on, but the general desert is left alone. I just love that!

RW: I love how you’re putting it. No one has tried to “fix” it.

RB: They haven’t even bothered, you know? The desert is just so real!

RW: You spoke in your talk at CCA of your love of Pyramid Lake. Would you say something about that?

RB: I love Pyramid Lake. First of all I have a kind of sentimental connection there that goes back to my childhood. We used to go out there from time to time. My dad liked to drink and when we’d go on a fishing trip, for instance, it was pretty typical for him to have a beer between his legs driving down the highway in the middle of Nevada throwing the cans out the window and getting another one.

He liked to drive out to Pyramid Lake for a little sojourn. He’d go to this little tavern there and drink for an hour or two and we’d screw around down on the beach. There were these myths that there was a serpent in that lake and you had to be careful swimming there. And for me, as an adult, it still represents a kind of mystery and a bit of a hallowed space. On the east side, where the pyramid exists, there’s nice little cove and on the shore there are these tufas. Have you been there?

RW: No. But I’ve seen the tufas at Mono Lake.

RB: The tufas sometimes look like three, four ice cream scoops on top of each other. They might be 60 feet high. And sometimes, when they’re clustered, you can climb them. They’re real toothy, like coral. On the very top there’s an open pot, a crater. It’s like a fort. These things are amazing—just like from another world! Those are juxtaposed with the pyramid, a giant rock structure which, come to find out, is simply created by geothermal hot water rising from the ground that is so calcium rich that, as it gurgles up out of the lake bed right there, it begins to deposit and just keeps depositing! To this day, hot water is leaking out all around the base of that pyramid.

One time we decided to circumambulate the whole pyramid. When you get on the far side, there’s very hot water squirting right out constantly like a hose bib turned on full. At the northwestern end are these things called the pinnacles. These things are flat out amazing! They rise up and you can climb them. When you get on top there’s a generous space maybe five or six times as big as this whole floor. You can look down on the lake. There are minnows about this big [gestures] that travel in schools that are so large they look like clouds under the surface of the water. That dark value of the fish school moving, undulating and changing shape constantly, is an amazing thing to see from up there! If you inspect the sides of these pinnacles, you can see that they are created completely by microorganisms!

So Pyramid Lake has the Pinnacles and there are the tufas and the magnificence of the lake with its azure color, which is generated from the calcium particulate which is always present in the water. When the sunlight hits it, it refracts the light in a way that other lakes don’t. The water’s clean and slightly sweet because it’s slightly alkaline, and generally speaking, there’s hardly anybody there.

It has such an essential quality and there’s so much history that you can feel that’s been stripped and put before you. It’s impossible not to think about a vast amount of time and the influence of geologic activity. That’s why I love the desert.

RW: The desert. Yes. Well, I also wanted to ask you about something else. In high school you ended up in a class where you were introduced to clay. Tell about how that happened and about that first pot you made.

RB: Well, in my senior year I was scrambling to graduate on time with my fellow classmates due to the fact that I was ill much of my junior year. I was in the hospital for three months and home in bed, too. So when I entered my senior year, I had classes to make up. I found myself beleaguered by the amount of homework and found out I could drop an algebra class and still graduate. I heard you could go and take a crafts class where you just screwed around, so I went over to that class with no expectation of learning anything. Well, I left the office and I got to that class a little late. Everybody was working. I reported and gave the teacher my transfer slip. He looked around and said, “Let’s go over to the clay table.” He got a bag of clay out and handed me a rolling pin, and said, “Make a slab-built pitcher.” Then he walked away.

Well, I knew what a rolling pin does. My mom made pies. So when the bell rang, I’d finished my piece. It looked kind of like a cowboy coffee pot. It had a coffee pot spout on the side and a lid that had a knob on it that reiterated the pot’s form in reverse. And there was a side handle that reiterated the pot’s form once again. So even in that very first piece, I had some design consciousness going on.

Well, I knew what a rolling pin does. My mom made pies. So when the bell rang, I’d finished my piece. It looked kind of like a cowboy coffee pot. It had a coffee pot spout on the side and a lid that had a knob on it that reiterated the pot’s form in reverse. And there was a side handle that reiterated the pot’s form once again. So even in that very first piece, I had some design consciousness going on.

So I was done with it, and I already knew I liked this thing a lot. My experience making it was complete concentration, as much as I knew was possible at that time. I wanted to put it somewhere where no one would mess with it. So I climbed up on the counter and went all the way up to the top of these shelves and slid a plastic bag over it and left, very enthused and, in fact, in love with that thing.

The rest of that day, when a class had ended, I’d sprint down there, jump up on the counter and lift the bag off the piece and just look at that thing. Most of the time I’d bring a damp sponge with me and I’d just rub it. I’d turn it and look at it, and then I’d slip the bag over it and run off to my next class.

Then it came time to fire it. I glazed it and somehow the glazes worked really perfectly. It was a red, low-fire clay with a yellow shiny glaze. The glaze thinned at all the edges to show the reddish clay. It really worked out. The teacher liked it and put it in the showcase in the hallway. So every day I’d walk down the hallway and see my piece in there. So between falling in love with creating this thing and then getting some positive feedback, I was just gone, you know?

What I noticed back then was that for the first time I was doing something that was completely mine. Nobody was meddling with me, and I just loved that— the personal involvement and that freedom, complete freedom! It was mine! Everything came out of me, came out of my mind, came out of my feelings, it was just complete ownership and autonomy. No compromise! I mean it links a little bit to the idea of what a vehicle represents, in a way, of freedom. It was a very freeing experience, and I saw it as such.

RW: So that was a profound experience.

RB: It was very profound. It did build over time, but it started just like that. The trajectory was from the moment of that first class. Then I started the Potter’s Club and we were making more stuff. Then the teacher started saying, “I think you ought to go to art school.”

RW: I think you mentioned in your talk at CCA that before that class you’d sort of assumed you’d be a car salesman or work in the casinos like your father had.

RB: Yes. Up until then I thought I’d go to the University of Nevada, Reno, like all of my friends did, but knowing me and my indifference to academics and education, I had this expectation that I would just kind of drop out after a while. I’d picked up from my dad some interest in being a real estate person or a car salesman, or working in the gaming industry. There was one point in my life when my mother, my father, my brother and myself all worked in the same casino.

RW: What did you all do?

RB: My mom worked throughout the year either as a cocktail waitress or, in this case, she was a cashier. My dad was a Keno expert and a pit boss. My brother was a shift boss in Keno. Do you know what Keno is?

RW: Sort of, but not really.

RB: It’s derived from a Chinese lottery game that I’ve heard was developed when they built the Great Wall of China. There’s a piece of paper with eighty little squares and numbers from one to eighty.

I’m going to tell you about this, because it connects to my artwork a little bit in the funny way we learn things. In the old days, a customer would go to a kiosk where the paper is supplied and they would have an inkpot and a Chinese brush. You would take the brush and dip it in this blue ink and mark these numbers, up to as many as fourteen of them, and the black numbers would still show through. Anyway you’d mark the paper and then you’d bring it to over to me. I’d ask, “Sir, do you want to play this for sixty cents?” or a dollar? or whatever. Then I’d take a piece of live paper that had the actual race—we called them “races”—and replicate your marks with my brush. Then I’d write more information in the margins and then stamp them both with a date/time number. I’d give you my copy and keep your original as proof of exactly what you marked in case there were any disputes.

Well, certain Keno writers took pride in having a really nice brush, even customizing it, taking some hairs off or tightening up the farrel a little bit to stiffen it up so they could make beautiful marks that had a wide, and then a tail coming off, pushing left—that kind of a thing. It was a very Asian kind of aesthetic.

So I developed an ability with the brush, and I developed that in the gambling industry. [laughs]

RW: That’s fascinating.

RB: Anyway, that’s what I thought I’d do because nothing in school, up until that point, had interested me that much. But that teacher helped change my life. He saw what was going on in me and he nurtured that, and he put pressure on me. He said, “You need to go to art school.” I said, “Really?” And by the end of the year I believed him. There was no doubt that I had been struck, and it was going to be a life-changing experience. So, when I went away to art school I was as serious as I could imagine being. However, it wasn’t until maybe a year and a half or two years later that I realized that I was going to be more serious than I could ever have imagined before.

When I left high school I wanted to get a degree in art and come back and be just like my high school teacher. He was my hero. I wanted to make pots. I wanted to make things. I had no doubt about that. But how voracious, how prolific I’d be, well, after a year and a half or two years, I realized that I was so immersed in making things, and thinking about making things, that it exceeded my naive expectations. I realized I couldn’t be a high school teacher and be the artist I wanted to be. I saw that wasn’t going to work, but I knew I had to make a living somehow, so I upped my goal to being a college teacher and having a job that only caused me to work two days a week.

That would be permissible in terms of me being an artist. So what I’m saying is that something happened in that crafts class that very day, but it was going to get more complex than I could even imagine.

[There was a break. When we resumed, the conversation had returned to Brady’s family.]

RB: Well, first of all, my mother was from a fundamentalist, religious background that was extreme. So when she left home and eventually got married and had children, she in no way wanted to impart any of that to us. But little by little, a neighbor here, a neighbor there would say, “Hey, you want to go to Sunday school?” So a few times, I went. I was also in a foster home for a period, but it was kind of voluntary. My brother was put in one and I wanted to go and hang out with him.

RW: Is this after your father had left?

RB: Oh, yes. It was long after they’d been divorced. My father had remarried and my brother and that lady did not get along.

They first separated when I was four. I remember we all lived in Las Vegas. When they separated—I didn’t know what had happened—my mom and I drove to Reno, and then my dad and brother didn’t come for six months or a year. So that was a weird time. Then they came and we acted like a family. That lasted for a couple of years and then they got divorced. That went on for five or six years, and then they got remarried “for the sake of the kids.” They actually got remarried. That lasted for about a year and a half, and then they got divorced again. Now where was I?

RW: You were talking about your mother’s fundamentalist upbringing, and then Sunday school.

RB: Yes. At the foster home, they’d send us to church every Sunday. It was a Christian Science church, too. I’ve never read the Bible and don’t know anything about any religious structure of any sort. What I did like about going to church was that sense of community; that’s a beautiful thing that I think we all want, also. I love it when everybody sings together. So I’ve thought about my place with all that.

I took pre-Columbian art history when I lived in Mexico and I found I could really identify with their attitude about nature, and the power that nature had. They attributed a spirit and a power to each thing. A tree had a different spirit and power than a rock, and even an obvious power. If a rock hits you on the head it could kill you. There was a realistic and elemental response to the world—not contrived or symbolic.

It dawned on me at that point that religions other than Christianity made a lot more sense to me. Superficially I might know more about Zen Buddhism than any other, however the reason religion keeps coming up in my mind is that I see these religious themes in my work. Sometimes I see them after I’ve done them. “Hmmm. Look at that!”

It’s happened time and time again in fairly obvious ways and other people notice, too. Then there is a less perceptible quality in quite a bit of the work that connects to that. I have ideas sometimes that maybe haven’t been expressed as much that also might touch on western religion and icons and symbolism, even though I just said that I have no particular affinity to Christianity. I’m more interested in eastern religions. However I do think that all religions, in their most fundamental, pared-down format, have a similarity.

So getting back to this thing that everybody needs, I think that religion is essentially an affirmation, or a gratefulness, or a mindfulness, about being one part of this whole universe. We are a living organism. It’s just simply that. That feeling of being really connected is what all people need and want, but it’s hard for modern day people, more and more, to have that.

RW: Would you say that as an artist, working, you know already that there will be certain states you arrive at and then the next day, you’re not in that state. You know what I mean?

RB: Yes. I know. That’s why I think those experiences we’re talking about in nature, we think it was the weather that day, like with the dust storm. Those things are part of it, but there’s something else, too, some readiness to let yourself go into that, some ability to let yourself into that. And I think there is resistance to that, in some way, too.

It’s related to art. That state that can happen where you’re almost in a suspended place where you’re fully concentrated, fully concentrated, but not over-controlling. You’re part of that small universe, or part of the whole universe, in a way that is so poignant, so involved, but at the same time, so unegotistical. Stuff happens then.

For sure, there may be intent. It’s not like you’re wandering or floating aimlessly, but at the same time, you’re so open that, in retrospect, it’s kind of surprising sometimes. You think, “How did I even do that?” I think that’s where, obviously, the most creative things happen.

It doesn’t have to be quite that high a level all the time, either. That’s why one needs to work often, and put in fairly long periods of time working. That self-consciousness begins to erode and a certain kind of just being there and connectedness occurs with all the things that participate, the tools, the material and everything else. You begin to just fall into this place where something can be birthed instead of dug up.

RW: That’s a nice way to put it. I was interested in how earlier you were talking about the Shaker room. You used this word “depersonalized,” and you just spoke of getting into this space where the ego recedes. It’s interesting that there’s a lot of ego that often goes with art. Do you have any thoughts on that?

RB: Well, I’ve heard people say that a good artist has to be somewhat egotistical. It takes a fairly strong ego, but there’s a difference between being egotistical and even a bit selfish as a person, and standing next to one’s artwork and having a pretty high egotistical profile. There’s a difference between that and allowing that ego to disappear when the making process is happening so that something more genuine and more deeply connected to a feeling space and thoughtfulness can occur. If the ego is really a conscious factor, “I’m important, this is important,” those things go against the birthing, or the unveiling—against the possibility of something coming about, that “something” which some work has that’s hard to describe, you know?

About the Author

Richard Whittaker is the founding editor of works & conversations and West Coast editor of Parabola magazine

SUBSCRIBE NOW

TO OUR MONTHLY NEWSLETTER

Share Your Comments and Reflections on this Conversation: