Interviewsand Articles

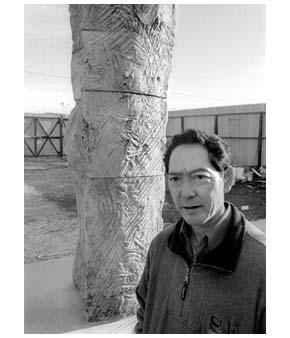

Interview: John Toki: A Gift to the Oakland Museum

by Richard Whittaker, Dec 23, 2008

One day I was visiting Leslie Ceramics and talking with owner John Toki when he told me he was making a gift to the Oakland Museum - The Toki Collection - 170 of the best pieces of ceramic art from the 450 pieces his parents and, later on, John himself had acquired in over fifty years of close relationships with seemingly every clay artist in the Bay Area and well beyond.

The project had taken over three years just in planning and was finally heading toward completion.

When I first met Toki a few years ago, he was occupied doing large scale ceramic sculpture, industrial design, writing and publishing books, teaching at California College of Art, running Leslie Ceramic Supply [retail, wholesale and manufacting] and overseeing Lockerbie, a manufacturer of power wheels for potters. [Since then, he's sold Lockerbie and started a new company, Toki Kilns.]

At first, I had some trouble believing it—how many careers is that? And I'd never seen John rushing around or showing any sign of tension. "How do you do it?" I asked.

"I do one thing at a time," he explained.

"You're a Zen Master, aren't you?" I wanted to say, but instead I just asked if he had a Zen practice.

He claimed he didn't and then told me, "I just stay present to what I'm doing, and do it the best I can. And when I'm finished I turn my attention to the next thing." Sounded a little like "carry water, chop wood" to me—and "when I sleep, I sleep."

2007 marked the 60th anniversary of Leslie Ceramics, the business John's parents founded. Over the years, they met, became friends with, and supporters of, many of the young ceramic artists who were their customers. Among these were Peter Voulkos, Robert Arneson, Viola Frey, Stephen De Staebler, Ron Nagle, Jim Melchert, Clayton Bailey and many others.

The Tokis knew them all back in the day when they were just artists short of cash. John's mother, Leslie, would take items in trade or simply send a customer off with the understanding that they come back one day in the future to settle up. Often the Tokis would buy a piece to help out, and John has carried on in the same spirit.

I asked John if he'd tell me more about all this and a few weeks later we met at his studio to talk. But first, he wanted to show me a new door he'd made for his large kiln; it was massive and designed to roll into place on a steel I-beam. He gotten the kiln from Stephen De Staebler twenty-five years earlier and now his days of bricking the door shut were over.

As we walked around, he pointed things out: "I have to weld this crack here." He pointed to the large blades inside a clay mixer. Turning around, we faced a huge tower crane he built to move heavy sections of his larger pieces, "That needs needs work, too," he said. "Most people don't understand what it takes to be a sculptor, all the work that has to be done to maintain a studio."

True. Only those who have done it understand. It's like that, isn't it?

As we made our way back inside John mentioned that he was thinking of retiring from teaching at CCA [California College of Art] so he could devote more of his time to sculpture...

Richard Whittaker: You're thinking of stopping, really?

John Toki: Yes. But I was up there yesterday [at California College of Art in Oakland] helping out.

RW: Are you just tired of it?

JT: It is more about the challenge. I need to be challenged. I have been teaching for twenty-five years. That's long enough. It is time to give someone else the chance.

RW: Okay. So let's talk about The Toki Collection. First, let me ask for a little background. It goes back to your parents, right? When they founded Leslie Ceramics.

JT: Yes. 1946.

RW: Had your parents moved here from Japan?

JT: They were born in the United States. My mother was born in San Francisco, my dad in Sacramento. He went to Japan when he was two and returned when he was eighteen. Upon his return he went to Fresno State and then transferred to the University of California, Berkeley, where he was business major with an art minor.

RW: An art minor?

JT: He was actually pretty talented. He was a competent brush painter who studied with Chiura Obata in Berkeley for many years. In addition to formal landscape brushwork I remember him painting funny cartoon like caricatures, often of Leslie. Let's put it this way, he was good enough to be considered for a job as a background painter at Disney Productions.

RW: And your mother?

JT: She was an artist, sculptor/pianist. She earned a music scholarship to the University of Colorado at Boulder. In high school she played classical music with trio's and orchestra's and won the all city talent contest for San Francisco. She was really gifted, good at drawing, painting, pottery and sculpture. She was also a life long Ikebana flower arranger in the Sogetsu style.

RW: So your parents had this strong art connection.

JT: Yes. They were more than just business people, for sure. Their friends were all artists.

RW: And they had this little business in West Berkeley?

JT: It started in the city of San Pablo, not far from here. It was about this wide [stretches his arms, laughs]. It was called "Leslie's of California." They made small ceramic containers for florists-boats, figurines...

My dad was an accountant for Mitsubishi in San Francisco and worked an extra job in a pottery where he learned about slip casting, plaster molds, glazes and firing kilns. He combined his business and finance skills to start Leslie's of California, a small manufacturer of ceramics produced primarily for the floral industry. I was four years old then and still remember peering into the spy hole of a big gas kiln to witness the flames, and also watching the water in narrow straw like glass tubes that monitored the gas pressure. I also remember a blue ball mill being unloaded off a truck, one that I use today in Berkeley.

RW: This was the equipment your dad used for his business?

JT: Yes. A ball mill is used to grind ceramic compounds to refine the particle size. Leslie and Rayer [John's father] would also teach classes in the evenings such as lace doll making, china painting, and underglaze decoration.

RW: Lace doll?

JT: Yes. Porcelain, lace-doll making. You take a piece of lace, dip it into colored porcelain slip, then drape it over a clay skirt and shape it into a dress. The piece is then fired to 2165 Fahrenheit where the lace burns out leaving the clay.

The business transformation from studio classes to selling equipment and supplies evolved as students wanted to branch out on their own and set up their own studios. They needed to purchase kilns, glazes, casting slip, and equipment. So Leslie's of California, the manufacturer and educational facility eventually became Leslie Ceramics, a general supplier of ceramic equipment and materials. Leslie Glaze evolved in the early 1950's because you couldn't just go to a local ceramics store and buy glaze. It didn't exist.

RW: So your parents started making glazes, too.

JT: Yes. Their own glazes, which we still make today after fifty years.

RW: I was surprised when you took me into the back a couple of weeks ago-I hadn't realized all the actual manufacturing you do at Leslie Ceramics.

JT: We actually manufacture thousands of gallons of glaze and clay materials annually. All of the glaze is certified non-toxic by an independent laboratory. Rayer experimented with lead free glazes around 1970. I've made a conscious effort to use safe glaze materials in our products. And since so many of our customers are schools, this is an important factor in our product research and development.

RW: So your parents started the business and it grew and they began to meet everybody.

JT: It seemed like everybody who touched clay knew Leslie Ceramics.

RW: What's the reach of the business? How far away do you have customers?

JT: All around here, plus we even have customers from Japan, Italy, Switzerland and Mexico. And also in Nevada, Los Angeles, Montana, Oregon-many people know us. Suppose you needed the chemical silver nitrate, or a special hard to find product. Customers would call us to find out where to get such materials. In the 1960's there weren't too many places for potters to get ceramic supplies or information. That was one of our specialties. We really worked hard for the artists and went out of our way to find what they needed like, for instance, china paint used for dolls, like for the blush on a cheek or an eyebrow, or the red on lips. It wasn't used much on fine art. I recall in the mid-1960's Jim Melchert and Ron Nagle wanted to use china paints for their artwork, so my parents went out of their way to find these products for them.

RW: You've told me that often artists would show up at your home. Would you describe some of that?

JT: Every week. It was fun. There was always music, poetry, pottery, or painting going on at home. One example: Ron Nagle and Jim Melchert played piano. They would come over and play with my mother, Leslie. They would play, impromptu, usually starting around ten-thirty. Everyone would have loosened up after a few cups of sake. [laughs]

I remember another evening when Peter Voulkos and his wife Ann were visiting. After dinner everyone went down stairs and into the garage to paint. Later I remember my mom describing how she observed Voulkos at the painting table. She said "Peter didn't just start out painting right away. With head down, he carefully stared at the paper, contemplated about what he was going to put down, and then started painting."

There were also many raku parties. My dad took a top-loading Cress electric kiln, turned it on its side and made it into a front-loading raku kiln. It worked great!

There would generally be dinner and then music or an art activity. Daniel Rhodes, from Alfred University, who eventually moved to Davenport, California, a small coastal near Half Moon Bay, was visiting with his wife Lillian. They spent most of the evening viewing teapots-we had a beautiful teapot collection acquired over many years, mainly from Japan-and they talked about the aesthetic of teapots and bowls. This is an example of a typical Toki, home event.

RW: You have a brother and sister. Did you all enjoy that kind of atmosphere?

JT: My sister Ellengale, who is six years older, moved out of the house when she was seventeen to go to the University of California, Berkeley. So I don't remember too much about her involvement with the art activities at home.

RW: And your brother?

JT: Yes, Walter. He's a professor at Colorado State specializing in particle physics. He's worked on projects in China, Japan, as well as in the U.S. In his postgraduate studies at the MIT he worked with Professor Sam Ting, at the CERN (European Center for Nuclear Research) in Switzerland. Professor Ting discovered the J Particle, which ultimately led to a Nobel Prize.

In high school Walter was studying and I was out there playing sports, running track and cross-country and taking wood shop and crafts classes. I thought I was going to be a successful track coach.

RW: And no doubt it could have been, right?

JT: I think so. Discipline was the word of the day on the track team. Everything I learned in sports applies to the process of building and sculpting.

RW: What did you learn there?

JT: Work ethic, the highest level of work ethic and there's always another day.

RW: Not to give up, in other words.

JT: Right. I competed for eighteen years and won enough races to understand what it took to win, and also what it meant to set goals.

RW: What were your events?

JT: Half mile, and cross-country. Some of my fondest memories were competing on the track. After high school I went to Contra Costa Junior College where I'm co-school record holder of the 2-mile relay. I still remember the time, 7 minutes 46.7 seconds. It was at Hughes Stadium in Sacramento, where my teammates and I all ran our personal bests on the same night. At state college I started shifting toward art, but meanwhile I ran just about every local race including the Bay to Breakers, where I placed in the top hundred, twice, to my surprise! In those days there were about 10,000 runners competing in the race.

RW: So tell me how your parents started acquiring art.

JT: Most of the pieces were presents. I remember Viola Frey came over with Charles Fisk one afternoon and brought a little watercolor drawing of two little figures. Then there was Jim Melchert who brought over a package for Christmas. This was in the 1970's when computers were starting to hit the market. Jim made a box wrapped with a computer like image that contained one of his abstract plates. It was a white earthenware plate with a black cobalt design and deep spiraling grooves. It was a Christmas gift to Leslie and Rayer. This is a typical story on how the collection developed, without our even knowing it was a collection.

RW: Who were some of the people who would show up at your parents' house?

JT: Ron and Toni Nagle, Jim and Mary Ann Melchert, Steve DeStaebler, Peter and Ann Voulkos, Vaea and his wife Brenda Luckin, Marvin Lipofsky and his wife Ruth, Clayton and Betty Bailey and their kids, Bob Rasmussen, Sakuma, and many other visitors from Japan etc. And a host of flower arranging friends. Mrs. Takahashi from Berkeley, Pearl Kimura from Oakland. Also, Jim Hackett a Haiku poet, along with his wife Pat. They were all regulars.

There was music on Sundays, usually a trio. I can't remember his name, but there was a doctor by day who was an avid musician on weekends. He played the harpsichord. There would be singing, poetry, music. In hindsight, I really appreciated the creative atmosphere. I would usually go running during parties and return at the tail end just in time for dessert! My parents and their guests were always discussing the aesthetics of a pot or sculpture. Art books were always on the table. I can still visualize the moment when Daniel Rhodes held up a tea bowl in the living room to discuss the finer points of a glaze and rim on the vessel with Leslie and Rayer.

RW: So the collection began almost just accidentally. How did it evolve?

JT: Yes. The collection developed the way most people collect, by gravitating towards things that they like. My parents would go to art fairs and would buy pieces. They wanted to be supportive of the artists.

RW: Did they concentrate on the artists they already knew who came into the store?

JT: Yes. But Leslie had to really like a person first, and what they stood for. This would be her first step. Can you imagine what this meant? We had an eclectic bunch of artwork. She would bring a ceramic piece home and I'd say, "Oh, my gosh, why did you buy that? Are you sure that was a good choice" [laughs]. In the end, it was about the spirit of the person who made the work. The artists really appreciated her support.

RW: It was your mother who was particularly strong in that way?

JT: Yes. But my dad went along and would buy things as well.

RW: What was it, do you think, about a person that impressed your mother?

JT: The quality of their spirit and soul.

RW: What kind of quality might that be?

JT: Here's an example: Stephen de Staebler. They were in class together at CCAC. Steve was twenty-five years old, so this was about fifty years ago. The teacher was Hiroi from Japan. I remember mom coming home and she said, "There's this wonderful young man named Steve de Staebler."

"So what happened?" I asked.

"He carried this stone up the hill for me." It was a stone they were going to carve. No one else would help and the stone was too heavy for her to carry. She always remembered gestures like that.

RW: Gestures of generosity.

JT: Yes. Generosity. Being true to one's own self and life spirit. Humility also went a long way too.

RW: I have a feeling that you must have inherited some of that from your mother.

JT: Perhaps I have a little bit of my mom's side. I have a heart, but also a tough side.

RW: The tough side. That's from you dad?

JT: My dad could be really tough. In hindsight it had more to do about decision making, about getting something right. My mom was very generous. Together, Leslie and Rayer formed a good balance. They both shared a great passion for art. I'm sort of half and half, at least that is what my wife, Pam, tells me. There is a certain toughness you need to run a business, or to do anything at a high level of quality. It is really a grind on a day-to-day basis, day after day after day to run a business. Art balances out the business and keeps me going from a soul level.

What I enjoy, well, you see in my store the artwork all around. That brings me a lot of joy, collecting and sharing things. For example one day a little piece showed up on one of the shelves. "Where did this come from?" I asked the staff. "Who made this?"

I remember saying to myself, "I must have that piece." Later I found out it was by Joe Kowalczyk, one of my employees and former student!

RW: I remember in 1970, I would go into Leslie Ceramics myself because I had a kiln and a little studio. I remember really liking the place. What I got, and this wasn't exactly conscious, was that having all kinds of ceramic art on display wasn't some sort of sales device. It was evidence of a feeling of appreciation and support for what people were doing. That's what came through.

JT: Very true, Richard. If you look at my business model, you'll notice that some of the beautiful art works are in the most important spaces. It goes against most retail practices of placing items in the "best locations."

RW: I think that's a quality that people can feel.

JT: Yes. I think the customers sense that. I don't sit down and think about that. I just put these pieces in the store so they blend in as part of the atmosphere. We had a Peter Voulkos plate right behind the cash register. That was the best spot in the store. Everyone loved Peter Voulkos, so we enjoyed it when he came into the store, cigar in hand, and saw his work!

RW: So artists made gifts to your parents. What were some of the other ways your parents got work?

JT: Trade. For example, we traded an electric kiln to Stephen DeStaebler for a big stoneware vessel. The trade usually starts because the artist needs equipment or materials. The David Gilhooly hippopotamus casserole was acquired the same way. I guess you'd say it was an old-fashioned barter system.

A typical Leslie Toki artist exchange would go like this: She would choose a piece from an artist and then say, "How much is it?" The artist would come up with a price. She'd give them the cash and they'd come into Leslie Ceramics and buy the materials they needed. The same thing happened with Clayton Bailey when he moved out from Wisconsin. He heard that Leslie buys artwork or trades for pieces. I remember her telling me that Clayton drove up and parked his truck on San Pablo Avenue in front of the store. She went out and looked in some boxes where she found a white plate called Eggs on a Cloud-so that's how the first Bailey piece was acquired.

RW: You've got several pieces by Clayton Bailey.

JT: We had five or six. He was one of our family friends. I still remember playing catch with his daughter Robin. That was in the seventies, a long time ago.

RW: So you've continued to acquire pieces of art and what has guided your choices?

JT: I'll give you some examples. One day Michael DeLeon said, "John, I really want one of your pieces." This conversation went on for about a year. He had a large piece that looked like a star: yellow and black and about four and a half feet in diameter. I said, "Well, why don't we just make a trade?" For me, it wasn't about what I was going to get but more about friendship through an exchange of work. You make a bond with someone when you trade something. He wanted my work, so I said, okay, let's make a trade. I told him, "I'm not sure this is an equal trade." His was four feet, and mine was fifteen inches! In the end we were both happy.

I tell the artists, "I'm just a caretaker for all the art works. I'm going to enjoy them and keep the collection together until they go to the Oakland Museum." I've worked it out and the museum will receive one hundred and seventy pieces-I call it "The Toki Collection, part 1." I've already started on "The Toki Collection, part 2!"

RW: I've looked through the master list of the work you donated to the Oakland Museum and some of the names surprised me. There's a piece by Squeak Carnwath, for instance.

JT: Squeak was a classmate of mine at CCAC in 1977-78. She was working in clay then. She saw the collection building and one day she just said, "I'd like to give this to you." I remember Squeak as very spiritual person with deep feelings, which came out in her artwork. She was a very serious and kind student, and also the hardest working gal in graduate school. She's the same way today.

RW: I understand she was close to Viola.

JT: Good friends. They supported each other.

RW: I also noticed a piece in there from Nathan Oliveira. That surprised me.

JT: Leslie studied with Nathan. One day long ago I remember standing in our kitchen in El Cerrito. Leslie came in with a black ink drawing of a little figure painted on paper. It was about eight and a half by eleven inches. All the edges were burned! What happened? Here I am, this kid viewing mom's art work. "Oh, my gosh! Mom's bringing home drawings with all the edges burned! What does that mean?" [laughs] The edges had to do with aesthetics of the image. It was really beautiful. I learned a lot that day.

I also remember the day when she brought home a beautiful little print, which Nathan gave to her. He really liked Leslie. On the back of the print is a letter he wrote to her, a beautiful letter, very encouraging. Leslie would keep all the newspaper clippings of his art reviews. There are some by Alfred Frankenstein, the art critic from the Chronicle [San Francisco Chronicle]. That was typical of Leslie. She was really involved in watching how artists grew and developed, and enjoyed their successes.

RW: You've got a piece in there by David Best, I noticed.

JT: Yes. David Best. At the time he was a young student at the San Francisco Art Institute. He was a frequent customer at Leslie Ceramics. I didn't know him very well, but remember him coming into the store once in a while. Leslie bought one of his plates. It was about 18 inches in diameter with some press-molded faces on the plate. He is a perfect example of someone with tremendous determination, fortitude and personal vision. Now he is designing and building gigantic figures and projects at Burning Man, where he has built pieces over fifty feet tall. He also used to make wild looking cars with animal antlers and objects glued all over them.

RW: Right. He was one of the early people doing "art cars."

JT: He used to go to churches being torn down and would buy religious icons, and then use them in the construction of his art.

RW: Recently he built something in San Francisco, a temple or religious structure, that people got all up in arms about.

JT: [laughs] David! What is good about these people when you bring them up, Richard, is they are all pretty normal people doing some pretty way-out, extraordinary things. That's what's fun about human race. David Best is very good friends with Rene Di Rosa who has been a strong advocate and supporter of his work for many years. David did a lot of work at the Di Rosa property before it became a museum.

RW: And you've got some Robert Arneson pieces.

JT: Robert Arneson was a longtime customer and family friend. My parents really enjoyed him. I can still visualize his Fiat sports car pulling up in front of Leslie's on San Pablo Avenue. He would come in and purchase gallons of brightly colored low-fire glazes. He especially liked Leslie's white lava glaze. I remember him saying to me one day, "You should take all those glazes and start painting!" To this day that was a meaningful comment to me as an artist.

Arneson was always very quiet, and in fact he wasn't really funny at all. His humor came out in his artwork. I think part of the humor was his pain. He had numerous operations. I think his own fate was always in front of him. He had a hearing aid and I'm not sure what other health issues. I think he took a close look at himself.

My dad would often save plaster molds for Bob, any oddball plaster mold he thought Bob would like. During the nineteen sixties Leslie Ceramics was one of the largest plaster mold dealers, which resulted in us having an overstock of molds that didn't sell. I remember dad giving Bob a chicken mold. In return, he gave us a few little ceramic pieces. This is another example of how we acquired art works. One of the pieces Arneson gave us was called, "Lindsey Olive." It was a small hand-held piece based on the illusion of perspective. In actuality it was half a bowl. When you held the piece it appeared to be fully dimensional.

RW: You've got a Dick Marquis piece. How did you get one of his pieces?

JT: That piece was purchased by Leslie. To this day I can still see Dick, with his hat on and glasses, getting out of his truck and walking through the front door at Leslie Ceramics. He was known primarily as a glassblower, but he also worked in ceramics. The teapot in the collection depicts his hefty truck.

RW: We were both students in a ceramics class once. It was as if he had some magic in his hands. Anything he made just had some special quality about it.

JT: A little humor to it?

RW: Maybe that was it, or something. It was amazing.

JT: We also have a plate called Chubbies. It is a white plate with a silkscreen image on it. He probably learned silk screening from Ron Nagle. When I think about it, many of the artists who you have brought up were friends. They worked and played together, and shared information.

RW: Was Pete Voulkos part of that, too?

JT: Yes. Pete was a magnet to the entire art community. He was a very generous man. The Voulkos plate we have was a gift from Peter to Leslie. One day he walked into Leslie Ceramics and said, "Here Leslie, this is for you." I still remember that day. My mom was really happy!

He and Vi, his assistant, would come by to borrow our truck to move his work around. For ten years! Here are the keys. He'd come back and there would be a big dent. "Hey Vi, what happened?"

"Oh, I don't know." [laughs] We just looked the other way. I remember my dad bailed him out a couple of times. We could laugh about it. So Voulkos gave us the plate as a present. Everybody knew him. Gilhooly, De Staebler. Marquis. Everybody.

RW: Of course Melchert knew him.

JT: Melchert studied with Voulkos. He was very important in Melchert's career.

RW: I know Melchert became the head of the Art Department at UC Berkeley and that Voulkos taught there.

JT: Voulkos was teaching at the Otis Art Institute, where he was fired because the chairman of the department didn't like the direction he was headed in. He headed to Berkeley where he was hired to set up the ceramics department. He designed a studio with the largest front loading and car kilns in the area, and he also set up a bronze-casting foundry. I remember visiting the university studio in the 70's. It was a great environment. Voulkos made his students feel wide open to the creative process. A lot of young artists prospered under his leadership.

RW: I was surprised you have a Paul Soldner piece, because I didn't think of Soldner as ever being in the Bay Area.

JT: The connection with Paul was with his Soldner Equipment business in Colorado. He would visit Leslie Ceramics once in a while to promote his equipment. It is interesting, Richard. When you mention these people, I can clearly see them. I can visualize Paul getting out of his car, walking in with his wife and a minute later we're talking about clay mixers.

In the nineteen sixties and seventies, Soldner was very active teaching workshops around the country. He advanced the course of ceramics related to the raku firing process. He's a very dynamic individual and gentle soul. The abstract plate we have came from the Richmond Art Center where he conducted a workshop on raku. Leslie purchased it and it's been in our collection for thirty-five years.

RW: You have a Takemoto piece. Is that Henry Takemoto?

JT: Yes. We have a small plate. Leslie studied with Takemoto. I remember a story she told me about Takemoto. She said that when he wrote, he would never use periods at the end of a sentence. I thought, "Well, that's a unique way to communicate!" To this day, for some reason, I have always remembered this story. In regards to his art, Takemoto made big orb shapes with narrow bases, two or three feet in diameter. He would paint them with cobalt blue designs and cover the entire surface.

RW: So I'll mention a few other clay artists in your collection: Richard Shaw.

JT: A wonderful friend and beautiful person. We have a slab bottle painted with seagull designs. He called it "The Zit Bottle." The glaze blistered badly, so he scraped it all off and refired it. This was in the 1970's, when Shaw was taking the everyday common object like a couch, or chair and then painting the surfaces with images such as seagulls, ships, or cows etc. Shaw's father was a cartoonist, so he grew up around images with a sense of humor. Richard is a very generous, kind man. I remember when he opened up his parents' house in Los Angeles to my mom and Viola Frey when they were attending a ceramics convention. I remember my mom talking about how wonderful he was. I told him the other day, "Richard, everyone loves you."

RW: I didn't realize that he's taught life drawing at UC Berkeley for years. He really can draw beautifully.

JT: He draws a lot and has notebooks full of sketches. Richard is a man who has fun in life. He used to ride his bike from Fairfax, get on a ferry in Larkspur, cross the San Francisco Bay past the Golden Gate Bridge and Alcatraz Island and then ride his bike up Chestnut Street to the San Francisco Art Institute. Wow! That typifies Richard's energy! Later he was hired at the University of California, Berkeley, around 1988 or so.

RW: I'm wondering if any stories of other artists in the collection come to mind.

JT: Looking at the first page of artists in the collection, I think that Lesley Baker is coming on strong. She is going to be teaching at a college in Michigan where she was recently hired. For a number of years she worked with Richard Shaw as the studio manager at the University of California, Berkeley. Her specialty is images transfers on porcelain. Her works in the collection are beautiful, white slipcast porcelain, bone-like pieces purchased at the Mendocino At Center where she was an artist in residence.

Donna Billick an exceptional person! I call her superwoman, good at everything. In addition to her personal art work and public commissions she is working with the entomology department at the University of California at Davis where she integrates art and science.

Her specialty is terrazzo and large-scale public projects. I recall one time she showed me a model of a big public plaza. I only know two or three people who can actually pull of big projects like that. In addition to her artwork, she's also a distance swimmer. I remember her telling me she had just returned from a trip to Greece. "What were you doing there? I asked?" She said she was there to swim at an international swim meet. I said, "Donna, how far did you swim?" She said, "3 miles!"

Getting back to art. The piece we have in the Toki Collection is called Miss Mer, a mermaid, on a big crab about two feet wide. Donna is a great lady. What does that mean? I think the great individuals are generous with their heart. They give to life and make you feel positive when they're around. Donna is a great motivator, too, and can orchestrate large groups of children and adults. She built a fountain project and described the day the public was invited to make clay faces for it. She said, "eight hundred people showed up! We thought we might run out of clay!"

I helped her the other day on figuring out how to rig four-foot diameter clay spheres that weighed about 300 pounds each and had to be lifted over a twenty foot steel pole. Everything worked out and her installation was flawless.

Lisa Claque is a very talented artist with tremendous skill at painting and sculpting. She now lives in Tennessee with her family. I have a very poetic mixed-media, low-relief ceramic, wood, and metal piece by her in the collection. It includes a dried rose with gold leaf and small ceramic objects attached to an arching metal rod. The sculpture was given to me as a gift.

Peter Coussoulis's specialty is salt firing. The collection includes a salt-fired walrus. One of Coussoulis's contributions to the ceramic community in Northern California is his years of service managing the Walnut Creek Civic Art Center, where he has taught and organized some of the best ceramic workshops in the country.

Another example of a passionate artist and a meticulous craftsman is Bob Rasmussen, He went by the name Red Ekks. He taught for many years in the ceramics department at the San Francisco Art Institute alongside of Richard Shaw. He was a close friend of Fred Martin. The first time I met Rasmussen was around 1963, when he arrived at my parent's home in El Cerrito dressed in overalls ready to paint their house. He was a fine artist who, by day, painted houses to pay his bills. I was a teenager then, and remember hearing from my parents that an artist was coming to paint the house. I wanted to see how skillful an artist was at painting. So I said, "Can I help?" He let me sand the doors! That is my story on how I got to know Bob Rasmussen. I still occasionally hear from him when he calls Leslie Ceramics from Ireland.

Rob Fitiausi, formerly from Oakland, and now living in Fresno, California, is well versed in pit firing. He drives a backhoe tractor and digs foundations and footings to earn money to help support his art. He is a talented potter who can throw large voluminous pots. He pit and raku fires his vessels developing Zen like elegant and subtle surfaces. I bought two of his pit-fired bowls that are now in the Toki Collection.

Keiko Fukazawa is an artist from Japan who has terrific energy and spirit for life. I still remember her as a young enthusiastic artist arriving at my dad's house. She arrived in the Bay Area in search of a graduate school. We showed her around, but she eventually ended up in Los Angeles at the Otis Art Institute. A year later she was back visiting my dad. I said, "Keiko, where did you learn the English you are speaking? Do you know what you are saying?" Her peers were teaching her American slang at it's worst! She told me, "Oh, the students are teaching me English." [laughs] After graduating from Otis she taught ceramics to prison inmates. Since then Keiko has gone on to exhibit her work with Garth Clark Gallery, and is teaching at a college in the Los Angeles area. My dad helped her acquire a 10 cubic foot, Skutt electric kiln. She was very grateful and presented him with a few beautiful ceramic pieces that are in the collection.

Cynthia Hipkiss. She lives in the Sonoma area with her husband Carl and their children, all who are now grown adults and making art in the area. They have a store in the Sonoma town square where they sell their sculpture and jewelry. A few years ago I walked into the store being run by one of her daughters. We talked for a few minutes, then I told the young gal that I have known her mom for over twenty five years. I thought to myself, "What a great family unit."

In the early nineteen seventies Hipkiss was sculpting big ladies and would paint the jovial figures with bright, low-fire glazes. She told me her work sold well in Germany. Looking back, I wonder if the figures were self-portraits? Although she's not a rotund person herself! If you want to meet somebody with a positive attitude on all levels, then that describes Hipkiss. She gave me two pieces. One was a caricature of the woman who invented the TV dinner, and the other depicted the inventor of the bumper car. [laughs]

Ernie Kim. His roots go back to Montana when he saw Rudy Autio and Peter Voulkos in action. He spoke highly of Voulkos. Kim was one of my first ceramic teachers, at the Richmond Art Center, in 1967. He was a great potter, with an exceptional design sense. I learned more about art by observing him than by what he said. I got to know Kim while he was the director of the Richmond Art Center. Years later, during the 1980's, Kim would occasionally stop by my studio and help me. We often had dinner together at his house, where he also taught me how to make salad dressing, the perfect gravy, and how to made a great martini.

There are many artists who are going to go down in history as being part of the fabric of the community. James Lovera has been a steady force in the world of ceramics. We have a yellowish colored crater glazed plate of his. When I talk with my friend Ed Persike, who studied with Lovera at San Jose State, the word he used to describe Lovera is "gentleman." The last time I saw him he said, "John, the Smithsonian bought a couple of my pieces!" He was really excited about that. He's a true pleasure to be around.

Cecile McCann. You may know her as the founder of Artweek Magazine. She invited me to visit over a cup of tea at her house in the Berkeley Hills. She told me she just couldn't make a living doing artwork and that is one reason she started Artweek. She's made a great contribution to the arts through her magazine. What most people don't know is how talented she is as an artist.

RW: But somehow you got a piece of hers.

JT: She gave it to me. I call it The Moose. It's an oblong stoneware sculpture with blue glaze and jagged curved metal plates protruding from around the top. It looks like an animal. I really admire the piece and it's now part of the collection.

Okay. Tony Natsoulas. Tony is well known for his figurative caricatures. He studied with Bob Arneson at the University of California, Davis, and now lives in Sacramento with his wife Donna. I traded him clay, for the big face of a woman with red lips.

Kevin Nierman. One of his specialties is making raku vessels, cracking and then re-firing them, and then re-gluing them back together. Kevin has a terrific spirit. He founded Kids'N'Clay, the most successful children's clay program in the Bay Area. He's one of those individuals whose spirit lifts you up every day and makes you realize the value of life. We have worked together on fundraisers for the arts. Anyone who takes on a fundraiser for the promotion of the arts is my friend. Kevin and I organized a fundraiser that netted twenty-five thousand dollars for Watershed Center for the Ceramic Arts in Maine. His passion for life and the arts always seems to mesh.

RW: I've gotten a little peek into the Watershed thing and how much you've helped them.

JT: Lynn Thompson, former director at the Watershed Center for the Ceramic Arts, is someone who, when you meet her, you believe in her program. Her support of artists exemplifies the value of strong leadership in the arts.

Believing in artists and listening to what they are saying is also a reflection of our society. They're poets who design in three dimensions. Acquisition of their work confirms the value of their voice as a visual artist. Artists like to feel that once in a while. They're all pretty fragile. Someone says, "Wow, that sure is an ugly piece you're making over there." It takes some strength to say, "but this is what I've made."

RW: It may be that many of them are fragile, as you say, but it's more than that. It's just tough for artists to survive in this culture.

JT: It is tough for artists to make a living and difficult to find acknowledgment that their art has value in our society. We're a society that likes to measure and count things, especially money, rather than deal with emotions or feelings. Things that fuel the soul are often put on the sidelines.

But let me change of subject for just a second. I'm noticing that in the ten pages of names listed in the Toki Collection, there are many women who have contributed to the fabric of the San Francisco Bay Area art scene during the past fifty or so years. The collection includes fifty women, or about one third of the one hundred seventy artists.

RW: Say more.

JT: One influential artist is Ann Voulkos. She's an artist with a sensitive touch and a very natural aesthetic sense when it comes to shaping clay and glazing. When I look at Ann Voulkos's blue polka dot porcelain vessel with handles I think of some of Jun Kaneko's Dangos with big round spots.

Ann and Leslie were classmates at the San Francisco Art Institute. They were lifelong friends along with Maryann Melchert. The three of them would rotate studio's and make art together. She also had a positive effect on her husband Peter Voulkos. In fact, I asked her one time about influences on her husband. She softly joked, "Oh yes, he learned some things from me!"

RW: Well for instance, Sandy Simon, is an influential supporter of ceramic arts in this area.

JT: Yes, Sandy is terrific.

RW: We haven't mentioned Robert Brady yet. Of course, he is a very well known artist, but then there's his wife, Sandy, too.

JT: My mom studied with Robert Brady. He was a young artist back then starting out, but she really believed in him. Sandy studied at the University of Minnesota and has strong roots in functional pottery.

RW: I think it's a wonderful thing that Sandy has TRAX Gallery in Berkeley, a serious gallery honoring really high quality, utilitarian ceramic work.

JT: She has remained focused on functional ware by bringing in the best art ware in the country to TRAX Gallery. The gallery adds to the ceramic art culture of the area and features art potters such as Jess Parker, Warren McKenzie, and Curt Hoard.

RW: I don't think there are many ceramic collections like The Toki Collection in the whole country, if any.

JT: The collection is eclectic.

RW: So over the years this wonderful collection accumulated and then a few years ago you got this impulse...

JT: The impulse you speak of was the desire to show the work. The collection was exhibited in a show called The Toki Collection. It was first shown at the Pence Gallery in Davis, California, followed by an exhibit at the Richmond Art Center.

RW: So how did that happen?

JT: One day, Nancy Servis, Director of the Pence Gallery, and I were talking about the art work around the store. A Peter Voulkos plate, a Stephen DeStaebler figure, a Clayton Bailey plate, the Viola Frey figure etc. She said, "John, there's a story to be told through these pieces. You need to tell this story in an exhibition. We can call it The Toki Collection." We brainstormed ideas and decided to organize a show of the collection. But one of the big questions was where? There were four hundred and fifty pieces. They would all not fit into her gallery, so I suggested the Richmond Art Center. So the exhibition opened at the Pence Gallery and then traveled to the Richmond Art Center.

Rachel Osajima, Richmond Art Center Gallery Director, was instrumental in helping to pull everything together in collaboration with Nancy. This meant cataloging the art, labeling, and boxing each piece. It was a heroic task. Nancy organized a beautiful catalog and introduction, with essays by Rachel Osajima, Jim Melchert, and I. In 1998, the show opened. It officially put the collection on the map.

RW: It was probably a pretty neat thing for you to see it all together and exhibited.

JT: Oh, it was incredible to view all of the work at one time! Many artists included in the collection saw the show. The collection demonstrated to the public the diversity of ceramics produced in the bay area: narrative, figurative, abstract, tile murals, slip cast, stoneware, low & high fire ceramic, raku, as well as beautiful functional ware, wood and salt fired etc. It says so much about the richness and diversity of ceramics in Northern, California. It was quite a celebration for all the participants.

RW: So how did the process evolve from the point of having that show to your decision to donate the entire collection?

JT: Initially it started with the thought that perhaps I should develop my own museum. But I know from experience that it is one thing to start something and it is another thing to keep it going. I realized there are certain unknown aspects in trying to keep a museum going especially after one passes away. The purpose of museums is to take care of art works, educate the public, and provide a method of collecting, properly storing, and exhibiting works etc.

Meanwhile, I was working with Sue Baizerman, a curator at the Oakland Museum, and Lynn Downey, Levis Strauss curator, on a book project related to Arequipa Pottery from San Rafael, CA in the 1920's. I got to know Sue, and through her, met Karen Sugimoto and Phil Linhares, as well as Joy Tahan and others. Their dedication and focus on preserving art from California helped in my decision to donate the collection to the Oakland Museum. And since so many artists in the collection lived or worked in Oakland, Berkeley or San Francisco, the fit seemed ideal.

RW: And you've got all the major ceramic artists represented.

JT: Yes, the ones that come to mind are Stephen DeStaebler, Ron Nagle, Jim Melchert, Viola Frey and Peter Voulkos. And many others, who may never be known at a museum level, contributed to the fabric of the art scene.

RW: That's true. Now we were standing there at Leslie Ceramics not that long ago. You'd packed the collection and it was sitting on eight or nine pallets in your warehouse. I think I asked you, "John, what do you think all of this is worth?" You said, "Gee, I haven't tried to figure that out."

JT: [laughs]

RW: Then you said, "Half a million. Maybe a million." The point is, you didn't stop to figure out the dollar amount. But the truth is, this is a very substantial gift.

JT: It is. I could have paid off my house. Instead, I still have a mortgage. When you asked me about the artists-what are those qualities? I think I have to mirror those qualities in the way I'm giving the work away. Otherwise, it wouldn't be right. And so the collection was more about a contribution and what it can do.

RW: Is there something about art at the deepest levels that it should be a gift, not some kind of commodity?

JT: Yes, because the collection did not start out like that. Richard, as you know, when you ask the artists why they make the artwork, those with the true spirit aren't going to say it is because they are going to gain two dollars! So if I can help the artists by letting their voices be heard through the exposure their work, then I think I have done a good job.

There were other major components in getting the collection to the museum. One day I talked to Dave Peterson, a lawyer, about the collection in his Berkeley office. Later he happened to talk with someone who wanted to make a donation to the Oakland Museum for something having to do with ceramics. I got a call from a gentleman named Gene Savin. I thought Savin, Savin? I knew a Muriel Savin who studied at the Richmond Art Center. It was his mother! Gene was willing to contribute funds on behalf of a special ceramic project. I thought this was something of a miracle. It was a perfect fit and I said, okay, let's do it!

RW: You know most people, like me, don't give a second thought about some collection in a museum or about what is involved in that. The truth is, there's a huge amount of stuff involved.

JT: Money had to be raised to buy special cases for all the artwork. Money had to be earmarked to keep it going. Dave Peterson, who heads a foundation, I just heard contributed money to the collection as well.

So three components came together. The Toki Collection with the Savin Foundation and Dave Peterson's Foundation. I knew Gene's mom, Muriel. I now know Gene and his wife Susan. We accomplished this together, and it feels very good. I saw him yesterday. I said, "Gene, we did it!" His wife, Susan, was sitting there. She said, "Well, it took four years!" We've been working on this for four years!

Behind the scenes, Sue Baizerman and I worked every Sunday morning for many months organizing the collection for the museum. We set up three long tables in my Berkeley warehouse, and assembly line-like looked at every piece one by one opening up each box, pulling out a work, documenting and analyzing it. To take a collection and properly document it, store it and present it takes quite a bit of time and effort.

RW: Is there anything else you'd like to say about it?

JT: I appreciate the care and work by many people that's gone into organizing the collection. There's a space and label for each piece with dimensions, material type, name of the artist, and the dates-a real effort.

Going back to what I've told many artists in the collection, "I have been a caretaker along with my family of your art and have shared it with the public at Leslie Ceramics for many years. I'm now passing it on to the Oakland Museum of California where it will be taken care of for future generations to enjoy."

RW: You mentioned something to me about the artists' responses when they found out.

JT: Very excited! Agnese Udinotti, artist and gallery owner in Scottsdale, Arizona was very pleased to have her work included in the collection. Her presence in the collection is in part because she lived in San Francisco for several years. There are two angel figure plates in the collection that I received in trade for one of my sculptures that her daughter Alexis Stone and her husband Steve have in their yard. When I called Udinotti to tell her that the work was in the collection going to the museum, she said, "Oh John, that really made my day."

I had no idea the effect it would have on individuals. Everybody is happy! If you're an artist, and you learn that your work is going to be in a museum collection, it's a good feeling.

RW: It may not have ever crossed your mind, but I wonder if any of your own work is in this collection?

JT: No. [laughs]

RW: It's too bad, because it ought to be.

JT: Well, I do have two pieces on loan to the museum. One is titled "Blue Back" a twenty-foot tall, 12,000 lb sculpture. The collection and works on view at Leslie Ceramics have always been for the promotion of artists. I feel it's my purpose to showcase the work by my customers, friends and associates.

RW: This is great John. Is there anything you want to add?

JT: The Oakland Museum has just one more piece to pick up. It's a Stephen DeStaebler blue figure column piece. The Oakland Museum has a new 50,000 square foot storage facility, and from what I understand, it's state of the art. All the storage cases are in place.

I understand some of The Toki Collection pieces are going to be spread throughout the museum. For example, the Viola Frey Pink Lady is going to be placed next to Venus Woman to show a contemporary piece next to a more formal carved white marble figure. It will offer the public an opportunity to think about the past and the present. And hopefully this will help bring added joy to the art scene in the Bay Area while acknowledging what has been accomplished by so many wonderful artists. ∆

This conversation above took place in June of 2007. Fourteen years later, in April of 2021, I talked with John Toki about his own journey as a sculptor.

About the Author

Richard Whittaker is the founding editor of works & conversations and West Coast editor of Parabola magazine.

SUBSCRIBE NOW

TO OUR MONTHLY NEWSLETTER

Share Your Comments and Reflections on this Conversation:

On Oct 4, 2021 Shelley wrote:

Wow, what an article!!! The Oakland museum could do a retrospective of all the work donated. I’d volunteer! Extraordinary!!!!!!!On Feb 20, 2009 prakash kumar wrote:

it was very good conversation. i feled very nice tolking i proud and appriciated.On Jan 17, 2009 Eva Kwong wrote:

A terrific interview with a wonderful person and artist. part 2 -would be an interview on John's artwork.