Interviewsand Articles

Earning It - A Conversation with John Toki

by R. Whittaker, Apr 19, 2021

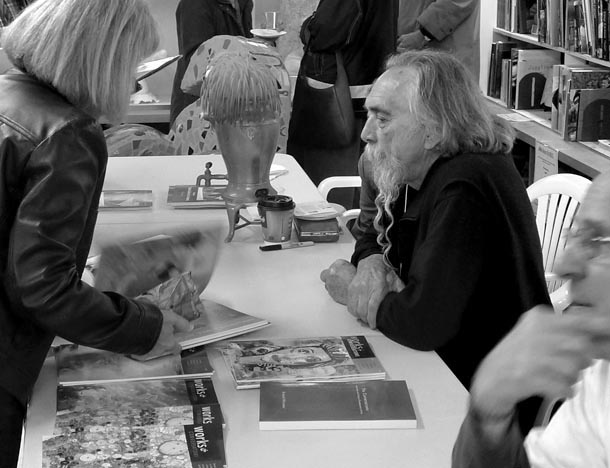

photo - r. whittaker

There’s always a lot one won’t learn about someone, especially those not asking you to focus on them - and John Toki is one of those people. It's not that he won't talk about himself. He doesn't volunteer.

It must have been twenty-five years ago and I was purchasing some clay at Leslie Ceramics in West Berkeley, California. The little store had been around for decades and it seemed that every potter and clay artist in the Bay Area knew the place and felt at home there. Examples of the work of scores of accomplished local artists were casually displayed around the place. I'd learned that Toki was an artist himself and that he owned the place. And suddenly I was curious; who was this personable man helping me at the sales counter? As no one was waiting for service, I started asking him about himself.

Within ten minutes, and without fanfare, I learned that the quiet man at the sales counter was essentially conducting five careers. Besides owning the store, he taught ceramics at the California College of Arts and Crafts (as it was then known) owned a company in Los Angeles that made potters wheels and kilns, was an author of books about working with clay, manufacted all the glazes sold at his store and was a working artist himself. Somehow he'd told me all this without it sounding like anything special, and I wasn't sure I'd heard him correctly. So I repeated what I thought I'd heard just to make sure. I had. And finding myself at a loss, I blurted out, "Are you a Zen master?" I was only half kidding.

It was the beginning of a friendship that has been more than just rewarding. It's been an inspiration and a great help. The time for a deeper dive into this extraordinary man's story was long overdue. So one day in April of 2021, I met John at his Richmond California studio to talk in earnest. And after nearly two hours we agreed it was a wrap. But I realized something more was needed and asked if he'd write something about his parents, and especially his mother.

I don't think we can do better than to begin with what he wrote...

“My mother, Leslie Toki, was a talented musician, painter, sculptor and Ikebana flower arranger in the Sogetsu tradition. I recall her making pottery and sculpture in her studio at home, and taking Ikebana classes with Mrs. Obata, in Berkeley. For as prolific as she was as an artist, she only exhibited her work one time! She was truly bent on art making as a reflection of her soul, not at all for practical reasons.

"When I was in elementary school my mother would tell me she practiced the piano eight hours a day - prior to her winning the San Francisco city wide talent contest. So I thought this was the normal number of work hours for artists.

"My grandmother, on my father’s side, lived near a pottery in Japan and made ceramics. So now it makes more sense as to why my father chose to found a ceramic company. One of my distant relatives was considered a ‘wise man’ of his city, and community members sought him out for advice! That must have been in the late 1800s.”

Toki is happy to tell stories from his life if you ask. This little historical note shows a great deal in a few words. But he’s just as content to leave his own stories untold. The way I see it, John embodies the principle that what one does speaks the most eloquently about who one is. More than almost anyone else I know, he inhabits life here and now answering the call of whatever is in front of him, whether it’s working on one of his sculptures, a new edition of a book, talking with a student, a friend, listening to a customer, advising a curator, or cleaning up his studio. The list is just a small example. In all these things, one meets a man who is very good at what he does. But beyond that and woven through the tapestry, is an unfailing generosity both in spirit and substance.

We talked at Toki’s studio in Richmond, California.

—Richard Whittaker

works: Let’s start with a little background. Now you are first generation American-born Japanese?

John Toki: I’m third generation, sansei. My parents are nisei, second generation.

works: Have you thought about how your Japanese heritage has influenced you?

John: Well, it’s very subtle. In growing up as an Asian in America and not seeing that many Asians – although in the Bay Area there are more compared to the rest of country – I always knew I was different. When I’d visit a friend’s home they would have a baloney sandwich. At home, we would have smelly fish that my father would be cooking, mackerel. And he cooked it on a hibachi - a little charcoal barbecue. That type of visual had a great impact on me – that I was different, not that I was better or worse. And at home we had very Zen type music. It was so abstract that I asked my father and my mother “What does this mean?” They said, “There is no exact meaning for these sounds.” And when I looked at their Japanese scrolls, that type of artwork was very abstract. It looked like Franz Kline’s contemporary abstract paintings! And I’m certain that my father had looked at some of those paintings.

works: Could he still read the calligraphy?

John: Yes. He was a very literate person, and so was my mom.

works: Do you have the language yourself?

John: A little bit. I can just get by in Japan.

works: You have two siblings, and where are you in the birth order?

John: My sister is the eldest. My twin brother and I are 69. So it was interesting looking at your last issue with the Doug Heine interview—“Pipe Fitting to Cosmic Particles”—because my brother, Walter, is a particle physicist. It was interesting growing up with a twin brother who was focusing in science. But really, in the end, it’s very similar to what I’m doing as an artist. I can see my particles, but he’s looking for particles you can’t see. But they’re out there. We were so different in school. He was strictly science and math, and I was out playing little league baseball, running track and cross-country and taking metal and wood shop. Walter was a total intellect, in a sense. We were very different, but now we’re close. Back then we were like two foreigners.

works: Now he was at Stanford earlier wasn’t he?

John: He worked at CERN, European Center for Nuclear Research, right out of graduate school at MIT. Then, he was hired at the Stanford Linear Accelerator (SLAC) where he worked for ten years. The laboratory in Palo Alto looked like something out of a James Bond movie, like the set from Doctor No—a cavernous space with metal grated walkways and giant cranes.

In hindsight, it really had an influence on me. Those cranes (they must have been 75-100 feet high) were moving what they call drift chambers. Walter described them as giant Campbell soup cans turned on their side with thousands of wires attached, and they were used for capturing particles.

The equipment, from my standpoint, was so incredible. I remember that part of one of the machines was built from a gun turret from a scrapped Naval ship. So I’m looking straight up and seeing these huge cranes moving a piece of equipment that must have weighed fifty or a hundred tons, and Walter was very nonchalant–“Oh, I’ve been on the phone trying to find rollers to move these around.”

Walter eventually took on a position at Colorado State University where he was working on the super collider project, while heading up the high-energy physics department. It’s really fascinating. When I asked Walter what the applications were for his work, he said, “It’s pure research.” And reflecting on what I’ve been doing as an artist, it’s also pure research. That’s really what I’m doing. So that’s a real connection.

works: What could you say about your own pure research?

John: In my mind, pure research is exploration of the unknown. And artwork is the perfect venue for that—the unknown. Can you imagine taking a lump of this soft, mushy material - clay - and then shaping it into something you’ve never seen before?

At one point, that was one of my goals. It’s really difficult. That says a lot about our influences. If you say “blue” well, that’s associated with the sky. If you say “red” that might be associated with blood. If you say “yellow” that might be associated with corn. It may sound sort of mundane.

One example of my exploration is that I painted one of my bedrooms black. I wanted to see what it felt like to be totally surrounded by a color that was normally not used to paint a living space. This was while I was trying to make the darkest-colored sculpture I could. With the next car I get, I’ve decided I’m going to have an interior that’s entirely red. Instead of going with something that seems to match the outside, I want to learn what it feels like to be totally surrounded with color. So that’s how I like to learn and explore. Art is really the greatest challenge.

works: It’s really interesting. You wanted to make something you’d never seen before and you found out it wasn’t so easy because all these associations kept popping up, right? You’d do something, and then be reminded of something…

John: Something else. Right. Oh, that looks like a tree. Everything always seems to be associated with something else.

works: How long did you pursue this exploration?

John: Well, I made a sculpture. [shows photo]. It took me ten years, Richard, to make. It’s called Spring Majesty. The goal was to make something that I’d never seen before and as abstract as I could. So this took me, literally, ten years. First of all, I couldn’t even move the piece. It was built inside this studio where we’re sitting. It started at that door and went all the way to those paintings on the wall. It was about twenty-seven feet long. I worked on it two or three years here inside the studio. Can you imagine keeping all that clay wet for three years? I used a garden hose to dampen the clay. It was exploration. I like to go into where there’s a certain unknown.

works: So you had this huge amount of clay and how did that work? Were there moments when, “Oh, that reminds me of something?” Then what would happen?

John: Well, when you work on something for ten years, you change.

works: What happened?

John: Where I started was one thing, but where I ended up was something else. There was always the question, “Is this piece good enough?” And of course, what does that mean? There’s always that concern. Who is going to see it? Then there are the practical issues. How am I going to fire this piece? How am I going to finish this piece? The reason it took ten years is because I couldn’t even move it. So I bought a crane from a catalog. Can you imagine? It was a kit, the biggest one I could find—6000 pound capacity. But it was only twenty feet tall and I needed thirty feet, minimum, to lift sculpture sections for a 24 foot tall piece. So I had it re-engineered to make it taller. I faced all these obstacles. They weren’t insurmountable. Working alone, that’s what took me ten years. I just stayed with it.

works: And it started with you wanting to see something you’d never seen before…

John: Yes. And now, when I look at this piece there are associations to the Japanese scrolls I saw as a kid and watching my dad do his sumi-e painting. I see, in hindsight, that some of his brush strokes were very similar to some of the surfaces of this piece. My dad was a very good sumi-e painter. I guess you’d call it a “hobby.” But he was very good.

works: Is that something he studied? Was it dear to him?

John: Let’s see here. At UC Berkeley, he was a business major with an art minor. He was good enough as a painter to be accepted at Disney Studios to be a background painter. He didn’t do that, and he never talked about it. And fifty years later I heard that he interviewed with Diego Rivera as a painter. He never talked about that, either. It only slipped out from my sister who told me, “Oh, yes, our dad interviewed with Diego Rivera to help paint the mural at Coit Tower (in San Francisco).” So for me, those are very meaningful links to his creative ability.

works: That’s fascinating. And I wonder if there was any connection with the Japanese tradition of brush painting with its inquiry into the self—that search to get past the ego, somehow.

John: Absolutely.

works: Do you think something like that was important for your dad?

John: I’m certain that it was. He was Buddhist. My dad was a man of few words. He never talked about any of that.

works: It’s mysterious, though. Don’t you think that, as children, we get these things whether they’re talked about or not?

John: We get them. And now, of course, all that’s very meaningful. It also means a lot when I learned that my grandfather put together beautiful flower arrangements. I didn’t know my grandfather very well. When I was five he was getting a little senile and he didn’t talk much. But just recently I saw a photo of him with a flower arrangement that totally changed my feeling about him. It turns out he did flower arranging – big ones! Three or four feet high. That reminded me of some of my aptitude for making large-scale sculpture: form, color, shape.

My grandfather also made soap. In the kitchen! So that’s one of the few vivid memories I remember as a four year old, about my grandfather - just those few things. And that was very influential. “Wow. My grandfather is making his own soap!” That’s pretty interesting. And it smelled so good that I tasted it. It tasted horrible! So these are little things about my ancestors.

works: That’s basic research!

John: That’s me [laughs]. And that’s sixty-five years ago. So today, I’m thinking, “Gosh, John, it might be kind of neat to make your own soap!” But instead of making soap I’ve made ceramic glazes for forty years at Leslie Ceramics. And I’m still doing that, now for the ceramic textbook, Hands In Clay, that I am writing.

works: That’s a fascinating connection, but let’s go back to this huge 24-foot piece you worked on for so long. Now you realize that its surface treatment is like the brush strokes your father made in his sumi-e paintings, and there were other things, too.

John: Yes. Like the scrolls. I used to see those big, long scrolls.

works: What that says to me is that something in this creative process comes from the unconscious.

John: Yes! I agree. The unconscious. How does one make a choice on what they do when they get up in the morning? I’m a planner, when needed, because I think you can accomplish more with careful planning like with a sculpture, or a book – I have to plan to finish a book. But with sculpture, there’s something really wonderful about pure exploration.

I like to go back to when I was a little kid playing with mud balls up in the El Cerrito Hills - digging in the mud and making them into softball-sized pieces of clay. I try not to lose those wonderful memories. Again, it was pure research - exploration!

works: Can you say more about that?

John: Oh, my Gosh! It’s of the moment. There are no rules. There are no regulations. You’re out there with your kid friends. That’s something I try to maintain now, as an adult. In this case, going out to my clay mixer and freely blending the porcelain and light buff brown stoneware clay developing it into a beautiful off white-brown striated color, trying to discover a new color; it gets harder as one becomes more knowledgeable in ones chosen field. Today I’m much better at preventing those big, giant cracks in the clay. But I haven’t forgotten how important the cracks are. It depends on where it goes, and what does it mean? A crack is not always a bad thing.

works: Yes. And so making those clay balls as a kid, you try not to lose touch with that. [yes] What else could you say about that?

John: I’d say it was true for all the other kids, too. The great joy about going outside in the fresh air is that you were playing. There was no script. You went outside and discovered that branch on that tree and you made your fort. And I used to dig holes in my parent’s back yard. I was in junior high school and remember digging a hole - it was maybe four feet deep - and I put piece of plywood on top. I used to sit in there and no one could find me. I’d be outside and my mom would be, “John, where are you?”

- I’d say, “I’m here.” But they couldn’t see me. And that’s similar to working in the clay - going back to that big piece I was describing, the most-abstract piece. It was solid clay. I would never do that again. But you have to find out.

works: That twenty-four foot piece was solid clay?

John: It was solid clay! I’m connecting it with this hole I dug in my backyard where I’d sit. It was fun, and it also felt physically cool. I was surrounded by this clay and this dirt. And that sculpture was solid. I had to dig a hole in the bottom of it that was almost the same size as the hole that I dug at my parents’ backyard. I didn’t know there was any connection until speaking to you today. It was a crazy thing. It took twelve or fifteen tons of clay to make it, and I had to dig a lot of clay out of that piece.

works: This is so interesting, John. And how many years ago was it when you made that huge piece?

John: It was in 1984 or so.

works: Like thirty-seven years ago. And that’s the biggest piece you ever made, right? [yes] At that point, how long had you been “officially” making art?

John: I graduated from Cal State Hayward [now CSU East Bay] in 1974. I studied with Clayton Bailey and it wasn’t too long afterwards that I started that project.

works: Okay. But before moving on, just listening to you describe those early experiences about making those mudballs - wasn’t there something just too deliciously joyful in that not to always want that kind of connection in your life?

John: Oh, god. It’s so wonderful, Richard! [laughs] The wonderful part is the freedom. I remember the freedom. I felt so much freedom – not knowing that I was free. But now, when I look back, I felt totally free.

I was the one who did all the raking and digging and shaping of my parents’ yard. There was no sense that it had any connection with sculpting. But I was really shaping the earth, and that’s my material now: clay.

works: Can you reflect on what it is about art making that’s kept you going now for all these many years?

John: I was twenty when I committed to being an artist. This space, where we’re sitting - I remember standing here in this same room; my dad was over there [points]. That’s when I made the commitment. It was an empty room then. I had nothing to show. I had a degree [laughs] - an art degree. What will that do?

works: This is when you made the commitment to having a life as an artist?

John: A life as an artist. I was twenty years old. I moved in here when I was a senior in college. I remember that vividly. I remember saying to myself, “I’m committing to this life as an artist.” The one side was really confident and the other side was totally scared. I had nothing to show except class projects. I actually made some pretty creative pieces following Clayton Bailey’s assignments, such as making useless cups.

works: I bet Clayton was a great teacher.

[photo: artist Clayton Bailey sitting in at the works & conversations table, Mar. 2012, open house, Leslie Ceramics]

John: Clayton was a wonderful teacher. He made me question what I was doing. He challenged me, and all the students - and his class critiques were really challenging and insightful. To this day that still holds very strongly - the notion of questioning myself as an artist, questioning what I’m making. It’s less about where it’s going to go or what it’s going “to be”—or its value.

The sense of value for one’s artwork is a tough one for a lot of artists, especially for young students, who try to place a value on their work, which, unfortunately, often becomes a dollar value.

works: What would you say about this big, big question of the value in art?

John: From my standpoint, the ultimate value of art is in nourishing the soul. Everything else is residual. A by product would be monetary value, possibly, and public acceptance. But you have to be careful there. I read that David Smith, the sculptor, said that when you make a piece, you’re up against every sculpture made throughout time! That’s a tall artistic order to face!

works: That’s an interesting sort of yin/yang there. It’s not to say that money, comparison and acceptance aren’t issues, but what is it that nourishes the soul?

John: That’s a good question. As humans we have our basic necessities. You eat, you drink water and you sleep. Then, what is the value of the rest of the day? It’s something about the intrinsic value of artwork that fuels the soul by - it could be by association. For example, when you see a field of flowers, that beauty fuels the soul. But I also notice that I see things other people don’t see. I’ll see something and see great value in it and others will just walk right past. Not that I’m better. I just have noticed this after all these years.

works: Can you give an example?

John: Definitely, with artwork. As a teacher, I could look at someone’s artwork and then know all about that student. I could just tell. I could look at the shape of an art piece as if it were an alphabet, turning it into a word - or by the color and how they made a transition. What did that mean? And of course having looked at so much sculpture, I can usually understand or possibly make a connection to a historical link. So I’m able to look at the artwork by others as if I was reading a book. I’ve noticed that’s something I can do that I realize not everybody can do. They can’t see it!

works: We’re talking about something deep here, don’t you think?

John: I think so. I was just born that way. Let me give you an example. My mom, Leslie Toki, was a very fine artist - a musician, very talented, a sculptor; she was really great. I remember her talking about being in Japan and looking at tea bowls on a tour. There was a very expensive tea bowl, wobbly and maybe kind of ugly. It was very Zen, and everyone else on her tour was buying these little two-dollar sake cups or tea bowls and wondering why she would spend so much on an “ugly-looking, wobbly piece.” But that piece had so much spirit. Just the movement in that bowl was so expressive. And I remember as a child that, “Wow! I really get it!”

Looking back, that was a profound experience, and it affects me as an artist today. I believe I have some of that, and maybe I inherited it from my mother – and my father, too. Another example would be some of the Japanese music – very abstract, esoteric music - that I was listening to at home. It was so wild and I would ask my dad, “What are they singing? What are they saying?”

He’d say, “It’s so abstract I can’t tell you. It’s just the sound.” So when we talk about art - an art piece, a painting, a sculpture – the one that’s lasting is the one that exudes a kind of energy that hopefully we, as receivers, can feel.

works: Yes. We don’t have very good words for these subtle things. And when I’m touched, like your mother could feel in that cup, it’s soul food, isn’t it?

John: It’s soul food, yes.

works: It gives life, doesn’t it?

John: It’s unbelievable.

works: I don’t know how much of a reader you are, John, but I couldn’t help thinking of The Unknown Craftsman by Soetsu Yanagi.

John: Oh, yes! I know that book. I love it [chuckles]—”the unknown craftsman.” I wonder who that unknown craftsman is? Yes. They’re doing their work.

works: Right. Yanagi was touched by the aliveness in their handmade cups and bowls that were totally free of ego in this direct way.

John: You can feel their soul in the work. It’s really beautiful. While growing up I remember my family would pull out all their tea bowl collection from a large chest when certain people would visit. Daniel Rhodes (author and ceramics professor at Alfred University) and Pete and Ann Voulkos were at our home, and Stephen DeStaebler, Viola Frey, Charles Fiske, Ron and Cindy Nagle, Jim Melchert—and family, of course. They would all start looking at tea bowls at 11pm [laughs]. Then they’d start playing music.

I remember them holding the tea bowls and turning them slowly, and talking about the aesthetics and the glazes. I was looking at this from a distance, not understanding why it was so valuable for them. But now I get it. The learning for me was just in watching them.

You can learn so much, and clay is a wonderful medium because that energy can be captured in the craftsman’s fingerprints, or in the squeezing of that clay - either in sculpture or on the wheel. It’s really beautiful.

works: Switching gears here, I thought it would be interesting for people to learn something about all the things you’ve done. When I first met you, John, you were running Leslie Ceramics—the retail store your parents had founded in San Pablo in 1946; you were manufacturing ceramic glazes for potters in the back of the store; you were teaching at CCA (California College of Art); you had written a popular book for people who work in clay…

John: Now it’s three books I’ve co-authored.

works: You were also running a manufacturing firm in Southern California making equipment for potters, like electric wheels and kilns.

John: In Beaumont, California—making machinery. I designed a lot of machinery for five years, parts and so on–pottery equipment such as electric wheels, banding wheels, and wedging tables. We made everything from scratch and even had a foundry casting aluminum wheel heads.

works: And meanwhile, you were always working on your own art. And this was all going on at the same time.

John: Yes. That’s all true.

works: [laughs] Now I just want to say, John, that when I met you, I had no idea of how much you were doing. That’s five careers on top of each other! And when I’d see you at Leslie Ceramics, you were always giving each person your full attention and never in a hurry.

John: [laughs]

works: You know, I discovered Leslie Ceramics long before I met you. I’d moved to Oakland and built a 35 cubic foot kiln from the Daniel Rhodes book. I made the burners and plumbed the gas line - you know, cut and threaded the pipe. And I had a studio in my backyard. Of course, I”d Leslie Ceramics for supplies.

John: Whoa! I didn’t know that! I love that story!

works: There was something about Leslie Ceramics. I just liked the feeling in there.

John: My dad was there, of course.

works: Ultimately, I didn’t have the patience for pottery. It was bad enough making my own glazes, but I was making my own clay, and without a pug mill.

John: [laughs heartily] Oh, goodness!

works: A slow deal. Oh, my god! [both laughing] Cone nine. Anyway, I realized I just wasn’t up to it.

John: How many times did you fire the kiln?

works: If I did it ten times, I’d be surprised.

John: Gosh, that’s impressive. That’s a pretty good-sized kiln.

works: Yes. But with Leslie Ceramics, I never forgot the feeling. There was something nourishing there.

John: It was probably from my parents.

works: In another interview you told me how your mother was very sensitive with all these young ceramic artists. She would trade supplies for their work.

John: Oh, my parents loved the artists. They were very supportive in their small way—a small way that made a big difference to the artists.

works: So quite a few years passed before you and I met. I was already publishing works & conversations. I’d done an issue featuring Viola Frey [#4].

John: I remember that interview! In fact, I still vividly remember seeing you at Leslie Ceramics the day you brought in that issue of works & conversations.

works: After I met you, one of the things I noticed was how you were with all your customers. Then when I learned you were doing five different careers, I began to wonder, “Holy Mackerel! Who is this guy?”

John: [laughs] One time you said to me, “John, you’re really busy, but you’re never in a hurry.”

That meant a lot to me. I was busy. But when I’m working with somebody they get my full attention. When I was working as a teacher, the students got my full attention. But when I left the classroom and went to my business I wasn’t thinking about teaching; I had to be fully attentive to my twelve employees. Then, when I was writing my book, I wasn’t thinking about school or my business, because a book really takes your full attention, as you know with your magazine.

I remember Bill Catling who used to work with Stephen De Staebler at his studio. He asked Stephen, “How do you do so many things, your family, your artwork and your teaching?

Stephen gave Bill the analogy that one sphere was his family, one sphere was his teaching, one sphere would be his art practice. He would pick up one sphere up at a time and move it a few feet, and put it down. Then, he’d pick up another sphere and move it. He said, “You don’t pick all of them at once because you can’t carry them all.”

It was a good analogy of how one can achieve certain things by picking up one item at a time and giving it your full attention. I watched Stephen navigate his life and I asked him sort of the same thing: “Stephen, how do you do so many things? Do you even have time to read a book?”

He said, “Oh, yes. I have time to read a book.”

So I try to be fully attentive to the task at hand— like fully, 100%.

works: Have you ever looked into Marguerite Wildenhain?

John: Oh, I know quite a bit about Marguerite. I never met her, but I knew of her as a high school student. I met people who studied with her at Pond Farm in the Guerneville (California) area.

works: Do you know how she taught?

John: I don’t.

works: She was in the first Weimar pottery class at the Bauhaus in 1919. They were using the old guild system. You were an apprentice and studied with a master. In the pottery, they had two or three masters—a master of form, a master of making and maybe a third. Then eventually, when you'd learned how to make pitchers that would pour without dribbling, etc. - you’d qualify as a journeyman, and you could go out to make a living with your own pottery.

Well, this is how Marguerite taught her students. You had to learn about the essential form of cups and bowls and plates, etc. and come up to this level where you’d be a good potter making useful ware. But you could aspire to something more, too. And that was learning how to make a pot with the whole of yourself. The people who could do that would have mastered something. She called that art. So what does that mean?

John: I would agree. So then it becomes individual. And she had her way of teaching students in her tradition. And wasn’t she pretty much of a taskmaster?

works: From everything I’ve heard….

John: It was her way or…

works: The highway.

John: Yes. The highway! [laughs] I’ve met a few people who said, “That’s me in that picture at Pond Farm. That’s when I had hair.” So I knew about her as a kid growing up. I heard a lot about her, and that she even charged a fee to people who wanted to see her work inside her showroom. I thought that was being very selective of her audience!

works: There’s a great story about her from Dean Swartz’s great book [Marguerite Wildenhain and the Bauhaus]. A student of hers, Wayne Reynolds, was getting very frustrated and one day Marguerite says, “We’re all going to start learning hand-building.” Wayne wanted to keep working on the wheel and besides, he didn’t like her strict way of teaching, So he thought, “Okay. I’ll show her!”

John: [laughs]

works: So he put something together that he described in the book as a “monstrosity.” Then critique time comes. Marguerite stands there looking at this thing quietly. Finally she says, “You know, it’s not bad, Wayne. If you were to do this - and she made some adjustments - it would be quite good!”

It was the last thing he expected. He writes, “I saw the clay coming to life under her thick, cracked fingers. I was in sort of a trance and I saw that I could do that. For the first time in my life, I knew I could do something I deeply wanted to do.”

Marguerite saw all that, and she said, “Why Bill, it looks like the lights just went on.”

John: That’s a nice story. Wow. Wowee.

works: Wayne Reynolds went on to become a lifelong potter.

John: Richard, isn’t it interesting how one incident can change someone’s life? You often hear about that in professional baseball. Often players toil in the minor leagues for years and years with a sandwich and soda for lunch and hundred dollars a day. I like those stories where someone stays with their dream. I think that’s what it’s about. In the arts it can be difficult, but it’s so rewarding - and you have the freedom to be expressive.

Life as an artist is hard work. Young artists often don’t understand that it’s not until they get out on their own, making art, and starting to dig around and unearthing themselves - before they can understand their soul, their spirit, and begin to know what that means. I’ve explained this to some of these young artists; I’m still around quite a few students even though I’m not teaching anymore. I explain that you have to stay with this.

The artists who have really been productive, worked really hard. Stephen De Staebler was working twice as hard as everybody else. Viola Frey was a super hard worker. Pete Voulkos, too - and John Mason. They were dedicated to their craft and worked steadily throughout their lives.

And to make a connection with my brother, Walter—he worked for a number of Nobel laureates: Professor Sam Ting out of MIT, Professor Burt Richter out of Stanford Linear Accelerator. He said, “John, it’s no surprise they won the Nobel Prize. They worked very hard at their science.” In their case, it was physics. In my case, I’m around artists. The artists are searching, and putting in the time in their field of study, because that’s what they like to do.

works: It reminds me that you’ve made some links between your earlier sports endeavors and said you learned something in competitive running that has served you well. Am I getting that right?

John: Yes. See all these little trophies? [on a shelf near his desk]. They were tucked away in my back room over forty years ago. These meant a lot to me. I decided to bring them back as a reminder of how hard it is, how much work one has to do in the field of art. I put these here as a reminder of the day-to-day workouts in track, and how similar it is to the discipline of making art, especially sculpture.

In art it’s the same day-to-day toiling away to get the artwork done. This little trophy is for the hour run. I ran over ten miles. The man listed above me on the stat sheet [a higher medalist] Rich Kimball, was seventeen. We were on the same Alameda Track Club team. He won the international cross-country championship. Anyway, these are reminders of the work ethic it takes to be an artist. So much of studio work is discipline. And sculpture is back breaking and dirty work, as you know.

You were telling me about your 35 cubic foot kiln. I can feel the sweat with you just talking about it! Making the burners! Threading the pipe! Putting that pipe clamp on, and the pipe starts to twist as you’re cutting the threads - putting the oil on there!

works: Yeah! I loved building that thing! And it was beautiful. So you were talking about persistence. Well, look, here’s a real problem. I can be persistent, but what if I never get any recognition? Is there some redeeming factor in all that work?

John: I believe recognition is a by-product. The artwork is something, hopefully, that you have imbued with soul and spirit whether it’s a painting or a sculpture, or it could be a conceptual piece, it could be a water feature, or a mobile. Many artists want recognition, but what does that mean? Many artists want a gallery, but how important is that?

I’d rather imbue the piece with soul and spirit. That’s going to be John Toki’s legacy. Recognition is just a by-product that somebody sees value in it. The advantage of recognition is that if somebody buys your art, it can help pay for materials for your next piece! But I am at a point where I’ve gotten a small amount of recognition.

works: You’re at that point where your sales can pay for your sculpture?

John: Yes. I am doing Okay! I talk to myself a lot—”John, hopefully you’ll sell one of these pieces because that will pay for that steel work and clay.”

I’m still there, Richard. It’s not easy. I still must be a diligent worker. It’s a humbling experience where I still must hope and pray to sell a piece to help pay for studio light bulbs, gas to fire the kilns, toilet paper, and brooms needed for sweeping the floor. Still, after forty-five years. It’s a humbling experience. But I love every moment of the process.

works: Now I don’t know of any artist making clay pieces of the same magnitude you are other than maybe Jun Kaneko, and he has a factory full of helpers.

John: Yes. He has helpers. I know them.

works: How many artists in the world, to your knowledge, make clay sculpture at the scale you do?

John: Well, in Northern California, not too many and not in Southern California, either. I can’t think of any.

works: Well, I think you’re one of the very few people in the world doing this.

John: I think so. There’s somebody, in India, a colleague of Ashwini Bhat from Petaluma, California. And there’s John Balistreri from Bowling Green University. He worked at the Kaneko studio making a series of thirteen foot tall pieces. Not too many people have the courage for taking it on.

works: Well, this is just a word to the wise. If you want to buy a piece by John Toki, you better do it before a lot of people realize what’s going on here.

John: [laughs] Jennifer Dowley who was working for the Sacramento Metropolitan Arts Commission, around 1982—said to me at the reception of my first public commission, “Be true to yourself.” I always remember that. So thirty-five years later I located her and sent her this catalog. I said, “Dear Jennifer, I always remember what you said, ‘Be true to yourself.’”

Working large scale is something I always wanted to do. It fuels my soul. Physically, I love the challenge. As an athlete, I’m used to it. It’s just what I like to do.

works: The way you’ve talked about art, it sounds like a spiritual thing and not at all about money.

John: It’s absolutely spiritual. I’m not a commercial artist. It isn’t my interest. The reality is that sales helps pay for material things, but I don’t make work to sell. I make work to fulfill my creative urges as a person and to explore the unknown, which is what we started talking about in this interview.

works: Is it fair to say that with this discipline and hard work that sometimes one enters a quality of experience we don’t usually reach in everyday life?

John: True. I visualize the process of making art as going on a long walk for miles and miles and miles and miles, and you get up over the hill—maybe the hill symbolizes the artwork—then you see the beautiful ocean and this sunset. But you have to earn it.

I believe quality of life is earned, not bought. Maybe this comes when your feet hurt and your shoes have holes in them, but you’re there, naked to the world, searching. You’re not born with clothes on. You go for this walk and come up over this hill and “Wow. That’s so impressive.”

In making artwork, I like that feeling of getting there on top of the hill and, when the sun comes out, it’s so awe inspiring.

The tough part about sculpture—and an example is that piece outside—it took me almost four years to build. I just finished it. There are certain things I really like about it. I’m still absorbing it. And right now I’m finishing another piece that recently came out of the kiln, a thirteen foot piece, I started three years ago. It took that long.

The long walk concept referencing a sculpture has gotten me to the point where now I’m up on the hill. But I have at least another six months to get this piece finished—the clay grinding, welding, galvanizing metal, fiber-glassing—all the unglamorous tasks that one doesn’t see. But I love it! [laughs] I love the mess and the resistance. There’s a certain amount of resistance when you have to move 500-pound sections of clay. It’s all relative; to someone else, five pounds is normal. To me, 500-pound sections are normal.

works: And you’ve helped others make this journey.

John: Oh, boy. I’ve worked with lots of artists from all over the world: France, Belgium, Germany, Mexico, Turkey, Switzerland, Spain, Portugal, Holland, Japan, and USA etc. Yes. They’re really happy people. Actually, there’s a gal, Karen Montgomery. I just met her yesterday. She called somebody who called somebody who called somebody who said, “John will help you.” That’s how it always happens. Someone calls me. Of course, I helped her. She was in need of a special kiln-firing program for her sculpture that was being fired at the Berkeley Potters Studio.

I was super busy that day at the studio, working on loading a kiln, working on the book, working on decal plates [to help the Berkeley Art Center] – everything; but I took the time to send her some firing programs. Anyway, her sculpture turned out great. It didn’t start out that way. After sending her a firing program, I rethought the process that evening and thought that perhaps it was too fast, and that the piece might blow up. I was really worried and contacted her late that evening, and said, “I think we should slow the firing down.” To make a long story short, it came out perfect! She ended stopping by the studio to visit, and we became quick friends.

When I’m going to fire my kiln and I have extra space, I call artists and tell them they can have the front of the kiln—five feet wide, fourteen inches deep and six feet high. Just fill it up with whatever you want. I have to fire it anyway. So it brings community together. And that’s really nice, Richard. I still believe in community. You know Karen Montgomery who was here yesterday—it was really last minute. I’d never heard of her. We had a great time and then I got to meet this gal from Persia, Doris Saberi, a ceramist and friend of Esther Rojas-Soto, my studio production assistant for the book Hands In Clay. So she brings this neat Persian culture to the studio. So that’s one of my offerings to other artists.

works: When you’ve made this long walk and finally come to the top of the hill and can see this ocean and the sun at the horizon—do you want to share this experience and help others get to this place?

John: Oh, absolutely. I taught for twenty-five years until I knew it was time to leave. So to be around Esther, who is helping me with the book, or to meet Doris from Persia and Karen from Shasta, or to help the Berkeley Art Center and the Berkeley Potter’s Studio… I’ve met lots of board members and directors. It’s my way of offering - maybe to advance the arts and culture and society through ceramics and giving them little tips on how to navigate their lives. Armin Haghnejad, from, Iran, is a new intern, and Youyou Hu is here; she’s from China, Yingling Lin, a former intern from Taiwan. Who else is here? There’s Minyue Zhou - she’s from China and a student at the California College of the Arts. I got a call from her professor, painter, Kim Anno. She said, “John, I’ve never called you before, but I need help” She asked me to help her student, Mia (Minyue), who had no kiln access, as the college was shut down during Covid. So I offered her the use of my kilns for a whole year. It was my offering.

There’s something special about a kiln, Richard. It brings people together because they need it to fire their work. I suppose this goes back to the earliest times of history where people would get together around a fire.

works: And your spirit, John, is like that warming fire.

John: I welcome them because, Richard, we’ve all been there in need of some help and I believe the best time to help someone is when they need help.

More here: John Toki and Some Reflections on Cultural Service

Interview - The Toki Collection - a Gift to the Oakland Museum

About the Author

Richard Whittaker is the founding editor of works & conversations and West Coast editor of Parabola magazine.

John Toki is a sculptor making large-scale ceramic work, an author, former art professor at CCA, an active mentor of young artists, supporter of local art centers and general beacon of light in the community of artists embarking on journeys of discovery.

SUBSCRIBE NOW

TO OUR MONTHLY NEWSLETTER

Share Your Comments and Reflections on this Conversation:

On Apr 8, 2024 Freda Karpf wrote:

the family connections, the mystery of the social ties and inner movement toward creation, the rich history of parallels and the reverberations of inquiry - just so wonderful to read these talks. inspiring; ultimately communal and stories perfect for any age; especially, i think for those of us older who didn't have the words or history to place ourselves in this delicious and rich tradition of creators. always a deep pleasure to read and glad these keep showing up in my inbox.On Apr 7, 2024 Tom Collins wrote:

This is a very fine an article about John Toki.I did meet him at Leslie Ceramics.

Probably when I worked with Peter Voulkos from 1979-1983.

I had no idea what a busy guy he was.

But always taking for when people needed him.

Great article and a great subject.

Thank you Richard Whittaker.

On Oct 21, 2022 Bunny Martin wrote:

IM so grateful to have seen this interview-John and I go back a long long time-I spent a year with him-and his students at his studio-doing anything that I could -every Friday as I took time from my own creative work to nurture another part of me. John was always patient and generous-what an amazing gift to the universe!On Oct 20, 2022 abbe rolnick wrote:

wonderful interview...the depth of the unknown connected to the soul. creating for the sake of creating with the only purpose being discovery and revealing beauty. Learning John's trajectory and even yours rounds out life. And yet we continue spinning in the layered universe. Thanks