Interviewsand Articles

Spirit Rock: A Conversation with Masahiro Nakajima and Janet Roth

by Richard Whittaker, Dec 4, 2016

Often discoveries happen thanks to a fluke. It’s how I ran across the Japanese practice of suiseki. I’d arrived at the Oakland Museum to plan a studio tour for the Art Guild. As I waited I began wondering "Where's the person I'm supposed to meet? Finally, I called her.

"We were going to meet tomorrow!" she said. “But listen, since you're there, check out the main hal. There’s a great exhibit there. Look for the rocks.”

Did she say “rocks”?

She did.

I like rocks. (Who doesn’t?) So I decided to follow her advice.

The Oakland Museum has a terrific collection of California art, and so my mistake quickly turned into an unexpected pleasure as I wandered through one gallery after another. Here’s a Viola Frey piece I’d never seen before, then a couple of paintings by Joan Brown, followed by an Elmer Bishof. Gosh. Then some Diebenkorn pieces and a couple of Thiebauds, to name a few.

Eventually, I spotted them. In several glass cases I could see one elegant stone after another. The natural beauty of each stone had an immediate, and quite familiar, effect. But soon I was looking for the explanatory text. And there it was: suiseki.

It’s a tradition in Japan: suiseki are natural stones that suggest natural scenes or animal and human figures. The stones should not be modified and are displayed as found (a single cut is allowed). When someone finds a stone that embodies such a quality, it’s collected and a display base, usually wooden, is crafted for the stone to sit upon. The tradition arrived from China where scholar’s stones had been collected and appreciated as early as the Tang Dynasty in the 7th century.

The morning’s utterly unanticipated discovery was like finding a new world. At the same time, it seemed like one I already knew about. I just called it “rock collecting.” So it’s not surprising that, on the spot, I decided to embark on a new investigation. It soon led me to Masahiro Nakajima and Janet Roth, president of the San Francisco Suiseki Kai. They graciously agreed to talk with me.

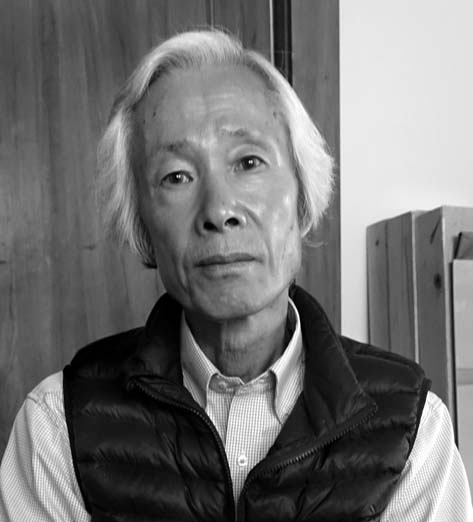

Masahiro [Mas] was born in Japan and grew up there in the 1950s. He came to the U.S., arriving in San Francisco in 1970. He remembers the day, March 1st. He was 21 years old.—R. Whittaker

works: What was your first impression?

Masahiro Nakajima: Kind of freedom, was my first impression. My friend, Japanese second generation, picked me up and drove to his house in Hayward.

works: Did you feel constrained in some way in Japan?

Mas: Yes, especially by family business obligations and expectations. And in 1970, Tokyo was very crowded, I mean terribly crowded all over. And transportation was not good—like China right now, with smog all over.

works: Was that the time of Japan’s economic expansion?

Mas: Huge, the beginning of a huge expansion in 1970.

works: You went to college in Japan?

Mas: I studied biochemistry, regarding sake making, because of my family business.

works: When you came here, did you continue in school?

Mas: Yes, immediately. My English wasn’t so good, so I went to school.

works: But not more biochemistry?

Mas: Not at all. I was more interested in business at that time.

works: Growing up in Japan, were you interested in art in any way?

Mas: Yes, but I never had a chance to think about what I wanted to do because of family expectations.

I grew up in the countryside seeing the tall mountains, snow mountains. Growing up surrounded by the mountains was part of my suiseki foundation.

works: Were you on a farm, or something like that?

Mas: It was a little town surrounded by different mountains.

works: Did you hike into the mountains?

Mas: Yes, all the time. Mainly just day hikes.

works: By yourself?

Mas: Many times by myself, but also, when I was a kid, with a group. Behind the elementary school there is a little mountain that you can climb up like in half an hour. And when you go to the top, you can see the entire little town. That’s a great feeling.

works: Did you find yourself looking at the stream and rocks and the plants and trees?

Mas: Unfortunately, when I was a kid, I didn’t pay attention. I was looking for how to swim in the river, and catch the fish.

works: Was it a relief getting away from other things in your life?

Mas: I don’t think relief. At home I was kind of free. I had curiosity and a major interest in catching the fish.

works: At that time, were you aware of suiseki?

Mas: No. I used to collect stones and bring them home, especially the petrified wood.

works: When did you first get involved in suiseki?

Mas: In 1980 I started.

works: How did that start?

Mas: I used to live in San Francisco for the first ten years, and at that time I was raising four children. We lived in the Sunset area, which is in fog all the time. Then we moved to Menlo Park. At that time I met a wonderful old man, Mr. Hirotsu. He invited me to his house and opened my eyes. He had wonderful stones all over, and he was also a teacher of suiseki.

works: I see. Is he still alive?

Mas: No. At that time he was over 80 years old.

Janet: Mr. Hirotsu was the person who introduced suiseki and taught it here in the Bay Area.

Mas: He established the Kashu Suiseki Kai. The history is 45 or 50 years.

Janet: It’s based in Palo Alto and still exists.

works: How did he introduce you to suiseki?

Mas: Our favorite place in his house was his workshop. So whenever I knock on the door, he’s so happy to welcome me. Then we have to go to his little workshop and we talk about stones all day.

At that time, I had already an art background; I went to art school here. And stone is kind of the way I grew up. Landscape stone, especially mountains, is my background.

works: Right. It’s deep in your past.

Mas: Deep in my past. And it’s so natural to accept that culture.

works: Yes. So you knock on Mr. Hirotsu’s door and he’s very happy to see you.

Mas: He was so happy to see me [laughs].

works: That’s beautiful. So how did you first meet him?

Mas: I don’t remember. Somehow we liked each other.

Janet: You were more involved in the issei community at that time, weren’t you? First generation.

Mas: Right.

works: Let’s go back to the little workshop. He welcomes you, and you go into the workshop and…

Mas: Lot of rocks.

works: So what would you be doing in there?

Mas: Asking which one is his favorite stone.

works: And he would show you one of the stones?

Mas: I remember over 35 years ago I was spending huge, huge time in his studio. We forget about time. At dinnertime his wife says, “You stay for dinner.”

“Oh.” So I call my wife, the previous wife, “I’m going to stay for dinner.” His wife was so nice, very warm-hearted. I felt like a grandchild.

works: And you responded very much to all that.

Mas: With my art background. At the beginning, I went to City College. Then I went to the San Francisco Art Institute.

works: And you got a BFA at the Art Institute?

Mas: Yes.

works: I wish I could have been there in the work-shop with you. Did he share that with other friends?

Mas: Nobody.

works: So that must have been pretty important for him.

Mas: Special.

works: And for you.

Mas: Of course. It was a long time ago. He was retired and so he had huge free time to spend with me.

works: And you’d be meeting around all these rocks.

Mas: Yes. And a lot of finished stone suiseki.

Janet: Do you want to show Richard the piece that Hirotsu-sensei gave you?

Mas: [leaves and comes back and sets a piece down on the table]

works: Tell me about this piece.

Mas: He brought this to my house personally. He gave it to me, not at the classroom. After we became good friends, he said he was inviting people in San Francisco to open the San Francisco Suiseki Kai. Janet is president of it right now.

Janet: And that was in 1982.

Mas: So in 1982 he asked me, “Would you like to join?” We called each other “Mister”— Japanese way. Not “Mas.” But for you I say “Mas.”

works: He would say Masahiro-san ?

Mas: No, no. Nakajima-san. He recommended me to join the San Francisco Suiseki Kai, not the Palo Alto Suiseki Kai, which was closer. Because he said he would teach there from the beginning.

works: I see. In the San Franciso club you would be learning about all this from the beginning.

Mas: Yes. Basic, everything.

works: Hirotsu-san’s practice of suiseki, was it grounded in a tradition? Or is it less formal than that?

Mas: There was no school available for him in this country at that time. In Japan, there’s a whole bunch of groups and schools, but here, he was a founder. He was the first man to do suiseki here. The only information that was available to him was suiseki books and magazines from Japan.

Janet: His club in Palo Alto is the oldest organized club in this country. It was almost entirely issei Japanese at that time. About the same time, there were also other Japanese immigrants teaching—some in Southern California and in Sacramento.

works: Do you have an insight, Janet, into the foundation of what suiseki comes from? I mean what’s the deep level it grows out of, or aspires to?

Mas: That, I was going to say. Personally, he constantly talked about how suiseki has a huge relationship with Zen. His dream was to enter the world of Zen through suiseki. That is his real background.

works: His own background was in Zen?

Mas: Religious belief in Zen.

works: Did Hirotsu-san have a foundation in Zen himself?

Mas: He was not a Zen master, but he had a huge knowledge about Zen. He was a scholar.

works: A scholar? Do you think he knew Daisetz Suzuki?

Mas: I’m pretty sure that he knew.

works: Did you ever meet Daisetz Suzuki?

Mas: No. But Hirotsu-san had a huge knowledge about Zen and Buddhism.

works: Is there ever any sort of formal meditation involved in suiseki? Or something else like that?

Mas: No meditation. No formal practice, like going to Zen center. The most important thing for suiseki is spirituality, how to develop spirituality. Just the stone itself is… What we are doing is not just for looks, or for showing the stone. Just like any art, your spirit is inside, in the deep background of stone.

works: Ah, beautiful...

Mas: So when you look at this stone—this is only one of many stones; he had a whole bunch of stones. And I was mid-30s probably, young man busy raising 4 children, when he gave me this stone. I was quite unhappy about this [laughs], because I didn’t understand at all his Zen philosophy. I was surprised. I was expecting a more traditional suiseki stone, which shows the beautiful landscape. This one is not really typical landscape stone at all.

This is very much like a spiritual stone. The more I’m getting old, I realize that what he really wanted to say is suiseki is not just style, not just beautiful physical appearance. This one has no beautiful appearance, but shows the spirit of Zen.

works: It’s beautiful what you’re seeing in this rock.

Mas: His meaning of Zen. It’s very quiet. Very humble. Very modest.

works: So it takes a long time to grow spiritually to where now you can see that…

Mas: I’m still too young! [laughs]

works: But you begin to feel the depth.

Mas: I understand now. I understand what he means. I’m pretty sure he believed this is the goal of suiseki.

works: When he gives you this stone, he’s trying to give you…

Mas: He really loved me so much. I mean, how many times I’ve been with him in his house all day. Now I realize that he was expecting me to carry on his teaching. Much Zen-style teaching is without words; he gave me the stone as his way of teaching Zen.

works: I’m touched to be put in front of this, and to have some feeling for its depth.

Mas: Depth and modesty.

works: This is a very difficult thing to grasp. especially in the U.S. This must be interesting for you, Janet—this topic. I’ll just call it a Japanese aesthetic.

Janet: Yes.

works: And you’re from the U.S.?

Janet: I’m from St. Louis. I think the most recent immigrant in my particular bloodlines came over in 1854.

works: Well, there you go. Can you talk a little bit about your own journey in suiseki?

Janet: Well, after I moved to the Bay Area, I was living in Berkeley. Then after I got a job, I moved from my little graduate school apartment down to Oakland. I’d seen photographs of bonsai, which now I would look at and say, “Those are not bonsai.” But I’d seen them and been entranced.

And after I got an apartment near Lake Merritt—this is probably 1982—I saw a listing for a show by the East Bay Bonsai Society. So I went. I was so entranced I even overcame all of my shyness and actually got myself to a meeting. Then I joined the group and started learning about bonsai, and that was my introduction to Japanese aesthetics.

works: Now, what was it that attracted you again?

Janet: There was just something entrancing about these little trees in the pots, and that was before anyone here really had good training and knowledge of bonsai. So I started that journey, and found myself in this whole community of people. There were many Americans along with immigrant Japanese, who were also hobbyists, but older and more knowledgeable. This community was connected to other communities studying Japanese traditional arts and people started introducing suiseki into the bonsai community. Just as in Japan, suiseki is often used where they will combine a tree and a stone—a suiseki and a bonsai.

works: It’s an interesting question—like what’s real bonsai and what isn’t? Or what’s well done and what isn’t? How does one determine the difference?

Janet: Well, with bonsai, it has to do partially with scale and knowing how to handle the tree and how to grow it properly so that it’s a healthy tree. So there are horticultural skills involved. There are also the basic artistic skills of looking for good composition; how to grow the tree so that it keeps your eye within the composition and isn’t running all over the place. There are formal ideas about that, which some people translate as rigid rules—formalisms that are sometimes fashion and sometimes a little stronger than that about appropriate ways of shaping trees. Sometimes they’re just fashions that come and go.

works: In bonsai is there a more developed aesthetic formalism than there is in suiseki? How does bonsai differ from suiseki around that?

Janet: They’re similar in that they both share some of the Japanese ideas about composition: the asymmetrical triangle, the use of empty space. But they’re very different, obviously. It’s a completely different medium. One is living, and always changing, and eventually dying. The other isn’t, at least not on a human time scale. But they both share the idea of bringing an abstraction of nature, and in a somewhat idealized vision of that nature, into your house or garden. If you have a beautifully maintained white pine, Goyomatsu—if it’s really well done—it evokes the image of an old tree up on the mountaintop. And suiseki is the same, you know. I sit here in the morning and look at that stone, the one with the flat surface and then the little mountain, and I can imagine myself up in Tuolumne Meadows or someplace like that. It brings that image into me.

works: Just to jump back for a second, when you went to school what were you interested in?

Janet: I studied astronomy and physics, and I had the idea that I was going to be an academic, either a physicist or an astronomer.

works: Okay. And then you, at some point, get into bonsai.

Janet: Yes.

works: All right. Here’s a question. A beginner is taught the rules and can begin trying to follow them. You look at the plant and study it. But if you stay with it, I’m assuming something else begins to develop. That’s what I’m curious about. You’ve absorbed the rules, let’s say, but then can another level of what it’s about, or something like that, appear?

Janet: I think I know what you mean.

Mas: May I say?

Janet: Yes, please.

Mas: In bonsai, one of the most important things is life and death.

Janet: That’s true. That’s the story a bonsai tells you

works: That really puts it into perspective. That’s the foundation.

Mas: Real foundation. How you patiently give it water every day, take care of the bonsai. Life and death.

Janet: We have an old juniper with dead wood and live wood all wrapped around, showing that battle. Or, I have a Stewartia tree, which is like a fine, mature, old, forest tree. It tells a completely different story from an old mountain juniper. But always, bonsai are old trees and display the characteristics of age.

works: I don’t think we have a cultural form for contemplating life and death, and its inevitability.

Janet: No.

Mas: And also, respect for all the trees. In Japan, they really pay attention and respect the old trees. It’s so beautiful, what they call beauty of the old tree. Here in this country, the attitude is often old man, old tree, old one—who cares? People love more flowers, big flowers and big trees.

But when you go to Sierra Nevada, or Yosemite, or Lake Tahoe, the high mountain area—Janet, you remember that photograph Ansel Adams took of the old tree?

Janet: Yes. The famous tree on top of Sentinel Dome.

Mas: He really wanted to capture the beauty of that old tree. That is core part of bonsai and very related to suiseki, also. Like this stone, it’s not stylish; this is very much like a wabi-sabi stone. It’s not flashy at all, but it has a deep, deep feeling inside.

Janet: One of the things I’ve noticed in this country and in Europe, is that so many people’s experience of suiseki seems to be in exhibitions. Particularly in Europe, it seems they’re very involved in winning prizes. And the best, deepest stones don’t win prizes. In an exhibition you walk right past.

Mas: Nobody would give Hirotsu-sensei’s stone any prize.

Janet: You wouldn’t even notice this stone; it’s so quiet.

works: Yes. In the suiseki club that you’re president of are there presentations about this aspect of it?

Janet: Yes. People bring in stones and we spend part of every meeting just talking about them. Sometimes Mas, or somebody else, will give a short presentation. It’s a fairly informal group. We go rock collecting together. I call it the perfect introvert’s hobby. You get to be alone together.

works: Are you a student of Soetsu Yanagi at all? There’s his book The Unknown Craftsman. And Shoji Hamada was part of all that I think.

Mas: I heard of Hamada-san, but no relationship.

works: I think Yanagi and Hamada reinvigorated something about wabi-sabi in Japan. I think they were a big influence.

Mas: So you know the word, wabi-sabi?

works: A little bit because it’s honored in ceramics in Japan, too. Right?

Mas: Yes.

works: Yanagi wrote about this simple, non-egoistic approach very eloquently.

Mas: By the way, I grew up in the pottery town.

works: In a pottery town?

Mas: All my surroundings are pottery makers.

works: Did you ever try your hand at it?

Mas: Yes, so many times at my friend’s place.

works: Did you like it?

Mas: Yes, I like it. I mean in Japan, in my hometown that was very popular classroom. Even in elementary school we had the classroom of pottery.

Janet: They’ve been making pottery in that area for centuries, and in current times they make a large amount of the ordinary housewares. It’s all these small family craft shops making this very high-quality handmade pottery.

works: I see. Do they have a central firing area, a central kiln, or do people have their own kilns?

Mas: Everybody has their own kiln.

works: Are there any wood-fired kilns?

Mas: Nowadays, very seldom to see wood fire, but when I grew up, the dark sky, smoke.

Janet: From all the kilns.

Mas: It was welcome. Everybody say, “business is good.” Like many years ago in England, when the Industrial Revolution was happening, they were so proud of their dark sky. I grew up like that. Especially ’50 and ’60, right after the war. Japan struggled to survive and develop. So entire little town where the pottery makers were really concentrating on how to survive.

works: Yes. How are you feeling about suiseki today?

Janet: I fell in love with suiseki when I first saw them. I was introduced to it by an American, Felix Rivera, who broke off from the San Francisco group to establish an English-speaking group to spread it among English speakers. And just like with bonsai, I can’t tell you in explicit words why I fell in love with it. It’s partially that love of stone itself; you pick up stones wherever you go and enjoy them. People have been doing that for many thousands of years.

works: Do you have any further reflections about the love of stones and rocks?

I know it very well in myself.

Janet: I don’t know, but I think it goes so deep. I was reading about this cave where Neanderthals had collected a bunch of stones. Obviously they were doing something there. Whether they were drinking beer or having a religious ceremony, who knows? And that was over a hundred thousand years ago.

Mas: Stonehenge, of course.

Janet: Right. I’ve been to Avebury. I’ve been to this wonderful place in Ireland—the Witch’s Hill I think it was called—with these old standing stones and what they call the passage graves made of stone. And there’s just this power. And I’m not talking in a superstitious sense.

works: It can be almost palpable, right?

Janet: Right. It’s almost palpable. And then developing my eye for stone in its natural form. Just in itself it’s an abstract representational piece of art. When you can touch it and feel the beauty of the stone, there’s this whole…[pauses]

works: It’s not easy to talk about these things that come in so directly.

Janet: Right.

Mas: One thing interesting to think about is people have the tendency to collect a whole bunch of stones and then don’t know what to do, just keep them in their garden. So many people said, when they came to our show, “Now I found how to appreciate the stone.”

We try to present it as an art form; that’s a very core part of our group, presenting the stone. And there’s collecting the stone. Looking at it later, you can enjoy forever the day you collected it—where you went, and the feeling of finding it.

Janet: This stone [pointing] has within it the memory of the day I found it and who I was with and what I was doing. It reminds me of Crater Lake, and so I remember the trip I made to Crater Lake with my mother. And then later, meeting Mas and him seeing this stone for the first time. The first gift he ever made for me was the base for this stone. So these layers of memory and imagination are there every time I look at this one stone.

works: That’s wonderful. Do you reflect at all on your earlier interest in astronomy and physics and how your feeling about them might relate to your love of suiseki?

Janet: I think there’s an interest in the physical world, an interest in how it works. Part of what comes along with loving the stones is also a real interest in the geology itself. You know, this piece of stone was probably created about 200, 300 million years ago. I have some idea of what the processes were that created it. And in terms of the connection between physics and art in general, physicists talk about theories, and the mathematics that express them, as “beautiful.” That sense of beauty is part of what signals someone that they have arrived at something true or correct. And it’s the very same feeling I experience when I see good suiseki.

works: Beauty, yes. And what if I were to say there’s something nourishing about this relationship. How would that strike you?

Janet: Nourishing is a good word.

Mas: Nourishing is one of the major aspects. But I would like to say one word: joy—joy! joy! joy!

Visit Mas and Janet’s website to see more.

About the Author

Richard Whittaker is the founding editor of works & conversations and West Coast editor of Parabola magazine.

SUBSCRIBE NOW

TO OUR MONTHLY NEWSLETTER

Share Your Comments and Reflections on this Conversation:

On May 29, 2017 Hank Wesselman wrote:

Wonderful. I have a stone from Tassajara in Big Sur that I found in the stream in 1980. It qualifies as suiseki and resembles a Chinese mountain. The stone has been a companion since it's revealing itself to me so many years ago. I have other stones as well...