Interviewsand Articles

Editor's Introduction w & c #17: The Precision of the Artist

by Richard Whittaker, Jan 12, 2017

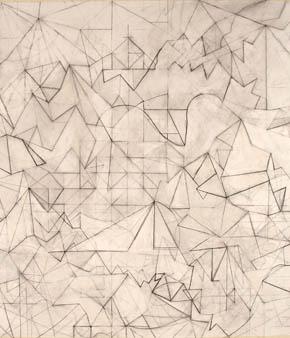

Celia Gerard, Aeon III [detail], 2007

charcoal, graphite and casein on paper, 44" x 44"

I recall listening years ago to a talk by Tibetan psychologist, Lobsang Rapgay, who spoke of the essential need for, and the difficulty of, what he called “aesthetic thought.” Through this, he said, contact with the numinous could be made, thus allowing its circulation in society. This contact with the numinous is needed to provide a basis for fundamental meaning. What exactly Rapgay meant by “aethetic thought” I’m not sure, but his words lodged in memory. Aesthetic thought must be essential to art’s most important function, opening some contact with forces which, as the Greeks believed, belong in the realm of the deities. We still speak of “the muses,” but without any feeling for the larger importance they might imply for us as described by Rapgay.

In a 1979 essay, Rosalind Krauss summed up the situation in the artworld as follows: “By now we find it indescribably embarrassing to mention art and spirit in the same sentence.” And as for the numinous, where does it stand today in such discourse?

Like the mind/body problem, there is the experience of the artist and then the art work itself. The mystery of art is that sometimes the two seem to become one. In such cases, the viewer is brought into the realm of the artist’s experience. Agnes Martin goes so far as saying there’s no difference between the two. If true, could it be only when, as Rapgay puts it, a contact with the numinous takes place?

We know there are invisible realms. The solution to a problem appears suddenly, and from where? But there are countless anecdotal stories of other things less amenable to easy hypothetical speculation. An imponderable portion of what is real escapes my awareness, but it’s also true that the edge of my awareness is a permeable membrane. Other people, too, are, in part, invisible worlds. Is art, at its best, a vehicle that can speak across these boundaries, a process in which the edges become more permeable?

In our lead interview, Jim Barton speaks of the “pure mathematics” of our interior world. It’s not a new idea. One can wonder if there isn’t a lawfulness that, better understood, could provide us with a new footing. Barton would say so. Tempted by the analogy of mathematics, the thought of zero came to me as fitting our interview with artist Hadi Tabatabai. For this artist, zero could be the sign at the door of the numinous, what others have called purity of intent, or emptiness.

As Enrique Martínez Celaya writes in our second installment of Guide, his meditation on art and value, “In art I confronted my life and tried to process it—and, in physics, I tried to detach myself from my life and find a purer place.” Martínez Celaya is a quantum physicist turned artist. To deduce something from that is to oversimplify, but no doubt rigor and investigation apply in both worlds. In his lectures at Cornell, Vladimir Nabokov sometimes liked to say, “the passion of the scientist and the precision of the artist.” He would pause, “Have I mispoken?” Of course, the answer was no. I believe Martínez Celaya’s work is precise, but according to what measure? The title of his book, Guide, could not have been arrived at without careful thought. Implied are points or principles of orientation to help lead one in life.

Contributing editor Jane Rosen describes Celia Gerard’s drawings as evoking landscapes, the energy of the body and an “eccentric spirituality.” They might work as poetic illustrations for Nabokov’s words, too.

In our Art of Living feature, we include an interview with Bob Woodsworth and Michael Levenston, co-founders, in 1978, of Vancouver’s City Farmer. Theirs is the story of two strangers coming together with a common vision and the drive to make it happen. City Farmer, as a precursor of permaculture, is an early instance of the promotion of what we now call “urban agriculture.” Why not turn that ornamental, water-guzzling front, back, or side, lawn into a beautiful vegetable and fruit-bearing organic garden of one’s very own?

Woodsworth was an early student of energy use in environmental contexts, a study largely overlooked in the early days of the environmental movement. The math was impossible to overlook. Growing food in your front yard saves energy! What’s more, it brings all kinds of other satisfactions and collateral benefits. Where neighbors are digging up their lawns and turning them into fruit and vegetable gardens, can a new feeling of community be far behind?

Last March, Lawrence Rinder curated an exhibit at Meridian Gallery in San Francisco: “Form +.” Inspired by a set of anonymous tantric drawings that Rinder’s friend, French poet Franck André Jamme owns, he brought together five artists. Included was work from Jamme’s own project, New Exercises, some of which we’ve reproduced here. I found them beguiling both in their depth and simplicity.

We also have a portfolio of photographs from Afghanistan by photojournalist Denise Zabalaga who, remarkably, traveled there alone after 9/11. Her photography, I think you’ll agree, transcends the genre.

And back from a long hiatus in these pages is J. Kathleen White, whose work is always impossible to classify. We also share with you five animal stories from Rosemary Peterson, which in part, show something beyond our ordinary knowing. The sad part is, I’m the only one who had the great pleasure of actually hearing them told. And, as always, we travel further into the world of Indigo Animal.—rw

About the Author

Richard Whittaker is the founder of works & conversations magazine.

SUBSCRIBE NOW

TO OUR MONTHLY NEWSLETTER

Share Your Comments and Reflections on this Conversation: