Interviewsand Articles

Untold Stories: Starr Valley: Photos from the Table of Contents

by Richard Whittaker, Apr 14, 2020

(a work in progress)

By the time issue #1 of works & conversations came along, eight years of my unplanned experiment were already behind me. This was in 1998. I'd had the domain www.conversations.org since I'd begun The Secret Alameda in the winter of 1990, and some clarity was coming into focus around my aim and how to proceed as the publisher of an art magazine.

The send-ups and humor of TSA had been terrifically refreshing for our small group of artist-friends, but I'd come to feel the ironic stance was just too easy. And wasn't the subtext of all the irony always some inarticulate vision of an unspoiled condition where the air was clear and the sky above was blue? I was angered by the way the Postmodern critique had a smothering fashion permeating the world of fine arts and found it not only depressing, but unconvincing.

Was the magic and hope that had been celebrated by Kandinsky and others in the early 20th Century, and later also in Abstract Expression, simply no longer possible? It was not a theorectical question. Transport and joy were repeatedly at the center of my own creative experience, particularly with photography, but not limited to that. Instead, the Postmodern Critique seemed to have discredited the very idea of the quest for meaning and beauty. Wasn't there someone who could redeem this sorry situation?

I was pondering this as someone with a degree in philosophy (1966 - Plato, the Pre-Socratics, Heidegger, the Existentialists in general and the late Wittgenstein all had spoken to me). As someone having arrived in San Francisco (Haight Street only a couple of blocks from where I lived) just as LSD and the Eastern spiritual traditions had arrived. And by 1998, besides having published 8 issus of The Secret Alameda and a single issue of Deus Ex Machina a lot had happened in my life. And instead of being intimidated by the critics I was reading, I was angered.

But who was I to take on such an ambitious thing?

On the other hand, if not me, who? I was the only one I knew who was really bothered in such a direct, personal way.

And so I'd taken it on, in spite of some fear and trembling.

And taking stock after eight years, I thought I had the material for a strong begining for this new title‚ three powerful interviews with three exceptional artists: Judy Pfaff, Squeak Carnwath and Richard Berger. Berger was routinely spoken of as a genius by the artists I met who knew him. My interview with Carnwath took place in 1992 while I was still producing The Secret Alameda, and it was an important verification for me. As it unfolded, I realized that exactly the kind of material I’d hoped to uncover was being voiced. For example, Carwath says: “In my work I’m trying to find the unmediated self. I think there are aspects of self that are unchanged, that echo the past, the present, and the future. I’m interested in that part of reality.” And then, “The practice of painting—I’m very involved in it, and so its natural outcome is this spiritual concern. If you consider it long enough and deeply enough a conversion experience will occur. On the other side of that conversion experience, or transformation, is an understanding of our fragility of being—and, really, we’re just witnesses.”

My interview with Judy Pfaff, took place in 1995 at the Pasadena Art Center College of Design where she was building her installation, “Ear to Ear.” Artist and friend Jane Rosen had been instrumental in arranging our meeting. I watched Pfaff at work in the gallery space. Soon she put down her MIG welder for a lunch break and some time to talk. We hit it off like old friends, and the interview remains as fresh today as it was then - a favorite for both of us.

As we began talking, right away I knew the 400-mile drive down to LA from the Bay Area was an effort well spent. “Where do you find yourself today in your work?” It was my first question.

Pfaff's response: “Up until about five or six years ago, I thought all the work was about exterior things—noticing how the light falls, or a tree grows. And if I went someplace, I’d think, ‘Oh good, now I can do something about what I see here—in Tokyo.’ Then suddenly, I saw it was really an interior landscape.”

The beauty of these statements, besides their inherent content, is that, considering the speakers, they're charged with that most elusive element credibility.

What did Roland Barthes know about it, when he wrote his famous essay, “The Death of the Author”? Was it true, that if you wanted to have entry into the real import of a work of art, you had to turn to an expert, someone trained in the complex subtleties of culture, language and the effects of power on meaning?

When I'd begun to encounter the divine energies of the Muses, I didn't know I wasn't qualified to understand the meaning of my own enchantment. And when I began reading the work of those who were speaking for me, and for other artists, I knew they hadn't a clue. Still, it took me a few years to discover the voices of other artists. And when I did, these were the voices I recognized.

That first issue of was published March of 1998. By then, I’d been an avid photographer for 23 years. I’d also been putting together an art magazine for seven years, The Secret Alameda. I hadn’t needed to contend with much recognition. In hindsight, it was a blessing. And by the time I’d decided to reboot with a new title, I’d formed a pretty good idea of what I wanted to do. One small piece of this was that I’d decided to use one of my photos in each issue on the table of contents spread. It was a way of integrating my own photography into the magazine. My name would appear only in tiny print at the bottom of the page. It suited me.

For many years my favorite lens was a Nikon 18mm rectilinear for my F3. Like many of my favorite photographs, this one was made with that lens.

The memory of making it comes to mind easily. For a number of years, I drove from Oakland to Boulder, Colorado to participate in a four-day workshop straddling the Memorial Day weekend. Usually, I drove out on Highway 80 through Nevada, the great salt flats of Utah, into Wyoming and then south to Boulder. Rolling along the Interstate at only a little more than one mile per minute, the wide vistas change slowly. One spots the snow-clad ridges of the Ruby Mountains far in the distance of Eastern Nevada before one is actually passing through them.

The first time I made this drive I noticed how, as I approached the Rubies, almost imperceptibly, my eye was drawn out. The beauty of the landscape registered without intention. The sagebrush, so typical, was more alive in a grayish, blue green way. And suddenly, I saw light reflected in parts of the green sward—water, snow melt from the range’s highest reaches. Increasingly entranced, I strained to see everything more precisely, and then an exit sign appeared: Starr Valley. Star Valley?

Mysterious. Because where was this valley? Looking west, only a wide vista stretched away. Looking east again, I scanned the lowest slopes of the mountains. There were large areas of green - pastures. It's ranch country. In some areas, standing water collected edged with patches of spring flowers. There would have to be streams, then.

I was closing in on heaven. That's what was happening. And except for the occasional ranch house along the base of the Ruby Mountains, there were no buildings. No sign of a town anywhere in sight.

Starr Valley

I took the exit. What did it matter if I spent an hour exploring this paradise? Now on a two-lane road, virtually deserted, I was skirting the base of the Rubies heading south. In places, enough water was flowing to form small streams that passed under the road through concrete pipes.

Everything was close by now that I was off the Interstate. It wasn’t long before a larger stream passed under the road and I pulled off on the shoulder. Stepping out of the car, I looked for a spot where I could get through the typical rancher’s style split wood and barbed wire fence. Finding one, I walked out into this landscape that seems so empty most of the year, especially from a distance. I found the stream and walked along it in the secret abundance that's so easily missed. This photo is the only evidence I took back with me, a small window, into what I found.

***********************************************

works & conversations #2 - Greeting the Light

Former publisher of Parabola magazine and later of Tricycle magazine, Lorraine Kisly, encouraged me when I was starting The Secret Alameda. She liked the idea of featuring the work of unknown artists. That was fortuitous because, as luck would have it, these were just the artists I happened to know. Nevertheless, I was still in thrall to conventional wisdom. In my first few issues, at least, I wanted to feature artists with a high profile. And making it more challenging, I had to be touched by their work, no matter how famous an artist might be. Even as an unknown publisher, and one with no money for honorariums, it was where I drew the line.

Fortunately, and perhaps as evidence of a hidden law, I had the right friend, artist Jane Rosen. Leaving her loft in Manhattan's SoHo District, she'd moved out to the San Francisco Bay area where she did some teaching at Stanford and UC Berkeley. Not only had she been key for our first issue, but she was essential for this second issue, as well. This is another story and one that will have to wait.

The image of these seven trees standing so solemnly together in the heat and lassitude of a remote desert landscape has remained alive for me all the years since I turned off old Route 66 onto to Cadiz Road on the hunch it might lead to something interesting. Where others might have seen only emptiness and dereliction along this remote stretch, I noticed these dry trees reaching upward, almost in prayer. The photograph felt right as a companion to my interview with artist James Turrell.

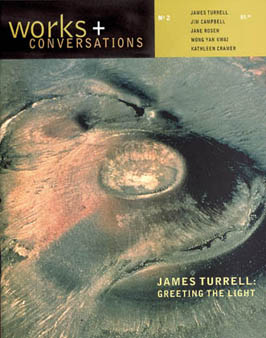

My pursuit of Turrell was finally realized when I sat down with him at his ranch east of Flagstaff, AZ in 1999. After a luminous interview, I was invited to visit Roden Crater with a small group that included a volcanologist from Hawaii. It was an unforgettable experience and I left with some great photos to remember it by. One of the most articulate artists I ever met, Turrell was careful to avoid explicit references to the religious or spiritual in his work, to say nothing of the depth of feeling that so naturally arises in response to light.

Perhaps no one had asked him directly about the obvious. I did, however, and was thrilled by his responses: “This work that I do is an emotional work. I don't think there is any doubt of that.” And closely afterwards, “I don't pretend to have a religious art, but I have to say, it’s artists who worked that territory from the very beginning. … I think that even when you go into gothic cathedrals, where the light and the space have such a way of engendering awe, that, in a way, what the artists have made for you in this place is almost a better connection to things beyond us than anything the preacher can say.” And then, “I would like to have the physicality of my light at least remind you of this other way of seeing. That's as best I can do. It's terrible hubris to say this is a religious art. But it is something that does reminds us of that way we are when we are thinking of things beyond us.”

This photograph made an inspired complement, I thought, to the conversation with Turrell and, in another way, it was a touching counterpoint to the deep sharing from the second artist in issue #2, Jane Rosen's friend, Jim Campbell.

I should say it became clear to me early on how photographs are labile things. They shift feeling tones so easily in keeping with the lens through which they’re viewed. The photo of the 7 trees can stand almost as a symbol of the inner landscape made visible in the conversation with MIT engineer and artist Campbell as he describes the substance from which his work is born.

Two examples will suffice: Portrait of My Father is a small photograph of Campbell's father hanging on a wall with two wires running from the bottom of the frame into a small metal box which controls what happens: the image of his father alternately fades from view and back into view to the rhythm of a heartbeat, which we understand to be that of his son, Jim. Photo of My Mother is similarly designed, but the photograph of his mother moves out of focus and then back into focus to the rhythm of his breathing. Both of Campbell's parents were handicapped and one feels an uncanny and deeply sensitive intimacy in these pieces.

It's tempting to try to say something more about this photo. David Parker, the extraordinary English photographer interviewed in issue #10 won't even say where his photographs were taken. He wants the photo to speak for itself. It seems right.

**************************************************************

works & conversations #3 - The Garden As Art

Three years into publishing The Secret Alameda, a creative idea came to me in response to the apparently eternal persistence of junk mail. Why not make an art installation from the unholy influx? In no time at all, I had an impressive pile of catalogs, brochures, fliers and bulk mail envelops of all kinds to contemplate — raw material. It was a big pile of… mixed media! But how exactly to use it?

Stacks! Big ones. All I needed was a spine of some kind, like a rod, secured on a flat, plywood base. Indeed. And soon, I was looking at three totems made from the unfortunate remains of former living trees. Hundreds of pesky envoys of dissimulation were now satisfyingly skewered like shish kabobs, six and seven feet high. It was a pleasing sight.

Gazing at them, Andy Taylor’s little second story place on Alameda’s Park Blvd. came to mind. It served as an occasional gallery space for our little art group—1350 Upstairs. Several more of these, I thought, and they’ll make a nice installation.

What could I call it? New Towers of Babble? Adverts Interruptus? Hijinks of this kind were at home in The Secret Alameda.

Then one Tuesday afternoon, let’s say, as I was sorting through the daily assault, one piece made me hesitate; I stopped to take a closer look. University of Chicago Press? Indeed, I was holding in my hand a list of their recent publications.

Well, I took a break and sat down to scan its offerings. Scanning down the list one title stopped me: The Garden As Art. I was sold instantly. How could a book with this title be anything less than a treasure? And so I ordered a copy.

A few weeks later, the much-anticipated book arrived. Unwrapping it, I soon had some doubts. Where were the visual treats? That was the first surprise. Quickly paging through the book, it dawned on me that I was holding a book dealing with rather technical matters, one that had required historical research and careful, scholarly explication. Not what I had expected.

It was my experience with that book that led to the third issue of works & conversations. That is, my disappointment and, to be honest, my indignation. While an appreciative understanding of scholarly research should have been within reach, I wasn’t able to find it. Instead, I was shocked that such a glorious premise had been reduced to such tedium.

This reaction lingered, and it wasn’t long before I found myself thinking about the most dynamic garden I’d ever seen. What’s more, I already had a sparkling interview with its creator, Marcia Donahue.

Somewhere in the wake of my disappointment, a new thought came into focus: perhaps this scholarly approach to "The Garden As Art" called for a counterpoint. It was an ambitious thought, but why not give it a try?

I broached the idea with Marcia, and she liked it. “I know a lot of really amazing gardens in the Bay Area,” she said. And with that, I felt a rush of enthusiasm. This dull, scholarly book, perhaps applauded in some remote circle, might be a gift. And in one luminous moment, I saw everything, as it were. It was so obvious. The question whether or not a garden was art was trivial. But it would be a good excuse to embark on a fine adventure. What could be a better project than making one’s own survey of unusual gardens—and settling only for those that sang like good poetry.

I’d already interviewed Donahue and that would serve as the anchor for the issue. Her quote could set the tone:

Gardening is working with hot material. It’s for humans. This interaction with nature, it speaks to you in a way that no other activity allows.

Yes. And did we need to spell that out? What did she mean?

The photos I choose for each issue are not necessarily among my favorites, but I want each one to act like an overtone in relation to the issue’s content. Donahue sent me to see Cevan Forristt’s astonishing garden in San Jose. It's where this photo was taken - or not quite in his garden. It was taken in an area behind the garden where he kept a variety of items in reserve, just-removed or not yet installed. Or items perhaps meant for some other project of his since he made his living designing extraordinary gardens for those clients willing—after preliminary discussion—to hand over full control to him. I liked the disorder here, its variety, all set off the large ceramic pot and its sidekick. I liked showing the pieces, the raw materials—all of them suggesting their own content, and all waiting to serve the gardener’s vision in a new order.

But let's come back now to the present moment. In order to review its content, I’d pulled a copy of issue #3 from my shelves. I took a look at the editor’s introduction, and saw I’d included a couple of quotes to set the tone. Twenty years had passed since then. And Looking at that first quote, I was stunned. “Gardens should have paths of uneven texture, leading nowhere.” —Davis Dimock.

I’d forgotten that I’d quoted my old friend, and so aptly. And I was stunned, because it showed that a very specific circle had reached completion all these years later. The current issue of works & conversations ( #37 ), featured a spectacular cover photo from a singular garden in Vermont—a garden decades in the making, and one that I’d kept track of in an informal way. The lead interview in issue #37 featured that Vermont gardener, a delightfully idiosyncratic man, who calls himself, not an artist, but an “art laborer,” someone I’d known for over forty years – Davis Dimock.

Seeing I’d chosen such an essence note from Davis to help set the tone for that issue so far in the past was like a small bolt of lightning. It revealed something in a flash - that there are deeper things in play in our lives than we know.

In any case, as I paged through the issue, I realized it was simply a small tour de force. One of its three interviews was with then chair of the philosophy department at San Jose State University, Tom Leddy whose interests centered around Philosophy of Art and Aesthetics, but reached broadly through Western Philosophy both modern and ancient.

What did he think about the garden as art? Our conversation on that question was fascinating and led to appearances from Kant, Plato, Aristotle, Heidegger, Nietzsche, Native American spirituality, Earthworks, Pop Art, Outsider art, the uses of gardens for social-didactic needs as well as for personal pleasure in a phenomenological - existential sense, the fundamentalism of post-modern thought and the necessity of everyday experience as a foundation for art. It provided something like a map of the conceptual playing field for the issue. And, if it marked one end of a spectrum, then there had to be a point at the other end—something utterly small and distinct.

Just that precise thing might have come in a little neighborhood in the small town of Tehachapi east of Bakersfield, California. It’s not so unusual to find a front yard transformed by the whispers of a Muse. The most humble places can harbor pieces of homespun magic. Over the years, I happened across quite a few examples of this wandering in towns enjoying the not knowing of where I was going. And I had a feeling for Tehachapi from earlier trips, often to Death Valley, or out through the Mojave Desert and beyond.*

So it was that I caught site of one front yard half a block away. Rolling to a stop I could see it was a minor bonanza of untutored creativity. No one was around so I grabbed my camera and began taking photos. After a few minutes, a white-haired woman came out to say hello.

As quoted in issue #3, Louresi said, “My husband had a habit of bringing home things he would find and I had to find a place to put them somewhere. Then, after he died, people kept bringing me things.” We chatted a bit and then another white haired lady came out of the house. “That’s my daughter,” Louresi said. We had a pleasant few minutes, the three of us.

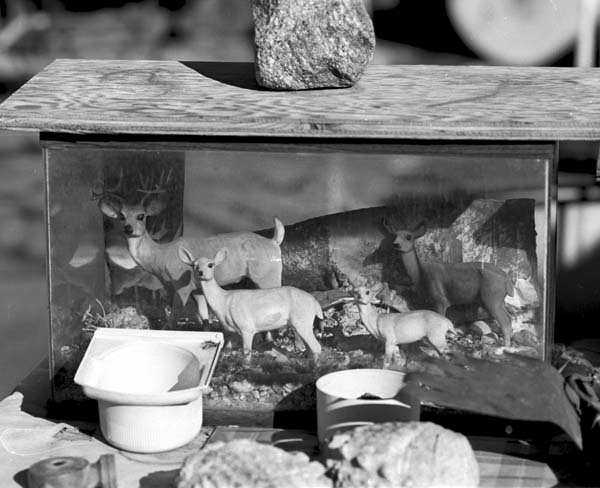

Before leaving, I asked Louresi, “What’s the story with the deer with its nose in the feedbag?”

“Bambi’s nose got broken and this covers it up,” she said. Simple. And doesn't this creative leap take us from A to Z—as in Zen?

************************************************************************************

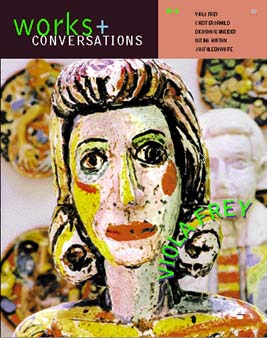

works & conversations #4 - Viola Frey

Wondering where to go for issue #4, Viola Frey came to mind. I’d thought about asking her for an interview for some time. Her work didn’t lift me the way James Turrell’s work did, or the work of some of the other artists I knew, but one thing was clear—Frey’s work was powerfully her own. The first piece of hers I’d seen was at the Oakland Museum, a ceramic figure of a man 9 ft. tall. It made a lasting impression, one that resisted my efforts to resolve. There was something cartoonish about it with its brightly colored glaze, aggressive body language and oversized head. On the other hand, it didn’t feel like a cartoon. I couldn’t figure out what it was saying.

So one day, I called painter Squeak Carnwath (the two were very close*). “What do you think?” I asked. “Would Viola Frey agree to an interview with me? And do you think it would be worth pursuing?” My questions were met with a telltale gap of silence. And then, Squeak responded. Yes, I could give it a try. She gave me Frey’s phone number.

In preparation, I read several things that had been written about her. Nothing made me feel she’d really been seen. I called Frey in June of 2000. By then, she’d been through devastating health problems—cancer surgeries and stroke—and part of what I wanted to know from Squeak was whether she would be capable of dealing with an interview. Squeak thought so. And finally, I decided to give her a call.

When she answered, I asked her if she’d been warned that I’d be calling.

“Yes,” she replied.

I waited, hoping she would say something more.

“Squeak told you I publish an art magazine and wanted to do an interview?”

“She told me.” Again I waited a few beats. Silence.

“Well,” I stumbled, “ah, I wondered if I could come down and meet with you.”

“You can come down.”

This might not be so easy, I thought.

The interview with Viola Frey, I sometimes tell people, was the most difficult one I ever did. It was also unforgettable because something I’d never experienced during an interview happened—two things, actually. At one point, in response to a question, Frey struggled to her feet, turned her back to me, and began to shuffle away. Interview over.

“Wait, Viola! Don’t go. Did I say something wrong? Please come back.”

She did, and we continued. That had been a shock, but it wasn’t the most memorable thing that happened during the interview.

As my efforts to get her to share something of her inner process were rebuffed, I began feeling more and more inept. It was not going well. I’d resorted to supplying what I thought must have been true for her and putting it out there for her to agree with, or not—to modify or otherwise locate in her experience. This turned out to be helpful. But each time I’d try to use her response as an avenue to some inner content, the door would close. Here’s an example.

RW: In one article a writer observes that in the large ceramic figures the women often seem to be in positions of reaction, while the men tend to have aggressive body language. You must have given thought to all that.

VF: All those things I’ve thought about a lot. But what I thought about them, who knows?

It was a situation I’d never run into interviewing someone. But let me back up a little. When I knocked on Frey’s studio door the morning of the interview, her assistant Sam Perry let me in. It was an old building in a mixed-use neighborhood of warehouses, some small manufacturing and a few houses here and there. I could see the place had once been a small business of some kind. Sam led me into a large studio area where I met Viola. She invited me to look around. Upstairs, she told me, there was more of her work. Sam pointed the way and I took advantage of the opportunity. It was a good-sized building, 5000 sq. ft, on two floors.

Visiting an artist’s studio is always revealing. Almost always, there are surprises and revelations, sometimes unforgettably so. I climbed the stairs and was left to myself to wander among decades of Frey’s work. Recalling the experience, I realize there’s nothing quite like it. I stopped in front of one piece after another, in no hurry. Taking each one in, I wondered what might come to light, just looking. Not knowing. Taking in. Seeing and not knowing.

There’s a feeling that comes, of an artist’s life. Some pieces I liked more than others. Some held my attention longer. And then I came to a wall hung with several large plates, each featuring a drawing. I stopped. What was going on with these drawings, I wondered—a horse with a skeleton riding it. Another plate featured two seated skeletons, each with an armless figure on its lap. Another featured two figures on a rocking horse, a boy behind a girl. What was I looking at?

I came back down the stairs and made my way back to the main studio space where a couple of chairs were set up. As we sat down, I believed I’d understood something I wouldn’t be asking about.

I set my Sony Walkman out on a little table and we began the interview. As I’d written, it was not going so well. In spite of knowing a little about Frey’s medical issues, I hadn’t thought too much about them. In hindsight, I could have given this more weight. It might have made it easier. Or maybe not.

No matter. About midway through the interview, I noticed something odd taking place. A feeling appeared in my chest of its own accord, almost as if it had nothing to do with me—a feeling of great tenderness toward this person sitting across from me. It felt like a small miracle.

When asked by others about interviewing, I always say that every interview is an adventure. Each one is a dance. This one brought a gift from another level, maybe a place where things are really seen. It’s not there in the words of the interview. But a few years later, at a dinner with sculptors Ann Weber and Sam Perry, it was a sweet moment when Sam said, “Richard, in that interview you really nailed her.” Perhaps I did. In any case, when I left, I knew I’d experienced something priceless.

I chose this photo for the table of contents for issue #4 because of the two ceramic figures – just the kind figures Viola Frey collected and often used in her early work. In our interview she referred to them as “the leftovers.” I took the photograph in a trailer park—I think it was in Quartzite, Arizona. As mentioned in issue #3, there seems to be a very human need to allow the creative impulse an outlet. One often sees the evidence in front yards. And no place is too humble for its appearance. Perhaps it flowers most easily in humble places. So I was curious what I might find in a slow passage through a little trailer park I’d spotted. Kitsch? I suppose. With the Dutch windmill and the plastic turf. But what about the white stone border with its the line of cactus plants? It’s a nice evocation of a world where water was plentiful—the Netherlands. And isn’t it cleverly adapted to a place where water is the scarcest gift?

About the Author

Richard Whittaker is the founding editor of works & conversations and West Coast editor of Parabola magazine.

SUBSCRIBE NOW

TO OUR MONTHLY NEWSLETTER

Share Your Comments and Reflections on this Conversation:

On Jun 5, 2020 Judy Kahn wrote:

This interview is like a small miracle.On Apr 15, 2020 Nancy Ingwersen wrote:

Wonderful!