Interviewsand Articles

A Conversation with Richard Whittaker: Berkeley Treasures

by Robbin Henderson, Jan 22, 2018

August 23, 2006

Introduction

I'm Robbin Henderson, the director of the Berkeley Art Center. Richard Whittaker is the editor and publisher of works & conversations magazine. Richard came to the Art Center several years ago and suggested that he'd like to do some collaboration with us. One of the things he suggested was to do a series of conversations with artists. We did several and then Richard came up with the really excellent idea of calling them “Berkeley Treasures.”

I thought it was a great title and, in fact, stole it for a series of shows we've been doing here, too. I also thought it was a great premise to bring artists to the Art Center audience who might or might not be well known but who, as Richard felt, contribute something to public discourse and the vibrancy of the arts community.

So we started this "Berkeley Treasures" series and Richard interviewed several people who are vital to the art scene in Berkeley. Recently we were casting around for who would go next and I said, 'Well, Richard, you're a "Berkeley Treasure." Why don't you let me interview you?' He was a little reluctant. But he generously agreed and so we're going to turn the tables on Richard tonight and let him be the interviewee. So you'll get to feel what it's like in that seat.

Richard: That will help my sensibility evolve, I'm sure [laughs].

Robbin: We've heard a little about your background, but can you give us a brief bio?

Richard: Well by the time I was twelve, my family had moved 12 times, including three times in West Virginia. When I was twelve, we moved out to Southern California. Dad us out on Route 66 like thousands of others. Growing up near Los Angeles, I went to various schools and finally, miraculously, got a BA from Pomona College. Then I moved to San Francisco in 1966. So I've lived up here for 40 years.

I didn't have a head start art-wise, but there was creative thinking on my father's side, and he was strong about not just accepting conventional views. It was important to find things out for yourself.

When I was 17 or 18, I was working for UC Riverside as a lab tech in a lemon grove, of all places. They were studying the effects of smog on citrus trees. The owner of the grove, Mr. Moffitt, struck me as the quintessential western man. He knew his way around all the back roads. Was relaxed and friendly. One morning I came to work and found out that Mr. Moffitt had committed suicide the night before.

It was a terrible shock. That night as I was struggling with it, I got an impulse to write out my feelings, and that turned out to be a revelation - the transformative power of that. It was an important discovery for me.

Robbin: I think one is particularly impressionable at that age. I think young people that age think a lot about life and death and the meaning of life and that sort of thing.

Richard: Yes. It reminds me that on another night - I was probably about fifteen - I decided to write down everything that I'd understood about existence up to that point in my life. [laughs]

I got one sentence down and then things started to get complicated. What exactly was it that I knew? But that impulse toward meaning that you're talking about, that's an important one. What causes that impulse to get buried, or trained out of us?

Robbin: I think that age is an incredibly complicated time of life. You're really in between a lot of things, but your mind is really starting expand.

Richard: You're speaking from your own experience, right?

Robbin: I think so. And also as a parent watching my children go through that. The whole beginning of questioning existence starts a lot younger than we usually think. Some kids can be very young and start thinking about life and death and the meaning of all of it.

Richard: Right.

Robbin: You mentioned to me some time ago that you had done ceramics at one time. When was that and how did you get involved with that?

Richard: That happened just before I got into Pomona College. I had a girlfriend at Scripps. She was taking ceramics and Paul Soldner happened to be her teacher. She took me into the ceramics studio one evening and Soldner happened to be there. Nancy gave me a little demonstration of throwing said, "Give it try."

So I wrestled around with the clay, and Soldner walked over and gave me a few pointers. The whole thing was really quite exotic being there on the Scripps campus with this beautiful young woman - and then with Paul Soldner, who himself had a remarkable quality. Of course he's a very well known potter.

After that I took a course at nearby Chaffey Junior College. If any of you have ever tried working with clay you probably know what a seductive experience it is to have your hands on the clay. It captured me. So I did that for a while and, in fact, was still interested in ceramics when I moved up here in 1966. I built a couple of kilns and I had a little studio. But I found that I loved building the kilns more than struggling with the clay and the firings, trying to throw a good pot and developing glazes and so on. But I did have some real experience with all of that.

Robbin: So do you think the tedium of production pottery was just not engaging enough.

Richard: It wasn’t for me. I'm kind of impatient. Anyone who has worked with clay knows that impatience is not a good match for that medium. I didn’t have an ideal of pure craft, either, where I might be searching for the sublime in a cup or bowl. Although, I did love some of the pots I'd created, and getting there wasn't easy or fast. Plus, it was lonely working out in my little studio. And coming up to San Francisco from Pomona College with a degree in philosophy, I was full of Existentialist ideas, and maybe my studio experience was a little too existential.

Robbin: But writing is a lonely activity, too, and you spend a lot of time doing that.

Richard: That's true, but writing can give you immediate rewards. Finding the right sentence, or even the right word, can be transformative, and it happens in a way I wasn't finding with the clay.

I should have been a better writer long ago, but I didn't really write that much. I did get some encouragement and by the time I graduated, I was on fire with poetry. In fact, I won a first prize in the Ina Coolbrith Poetry Circle and was invited to read at their awards ceremony with the five or six other winners. This was only weeks after I'd moved up here. Anyway, I collected rejection slips from journals and had to admit to myself that I was too shy, to throw myself into the fray with public readings in SF.

It's amazing how some people, right out of the chute, seem to know what they want to do and go right through life and achieve great things. That was not the way it was for me.

Robbin: That's hard to believe now.

Richard: I'm a late bloomer.

Robbin: Sometimes it just takes a long time for the flower to open.

Richard: Yes, for some people. Maybe I can be an encouraging example. According to me, it can happen fairly late.

Robbin: What are some of the interests that engaged you along the way.

Richard: Some books were a real help. Like so many others, I loved Herman Hesse, for instance. Probably the thing I've pursued the most in the last twenty-five years would be photography.

Robbin: And you still do that.

Richard: Yes. That began in 1976. But other interests? That's a hard question. I dabbled. I couldn't find anything I could really, wholeheartedly engage in. I worked in the post office when I came to San Francisco - the worst job I ever had. Then I got fired. It was a good resolution.

Robbin: [laughs] I know so many people who had jobs in the post office in the sixties and seventies.

Richard: I painted houses, too. I know a lot of people who did that. I worked for this Irishman, a real character. Climbing up these tall ladders and painting the side of a house in San Francisco's Outer Mission district or Glen Park or Oceanside and looking out across the city—it was pretty great. And listening to my boss, John McCaughn, telling stories about his adventures as a horse rider and nightclub singer in Ireland - that was fun.

Robbin: So when did you start writing really seriously. Did that start along with the photography or were they two separate activities.

Richard: They were separate. When I got out of school in 1966 I really thought I was going to be a poet. Wallace Stevens and T.S. Eliot were my models. I came up to San Francisco and was writing poetry, sending things out, getting rejection slips. I'd read at the “I and Thou” on Haight St. and that was a big thing for me, but I wasn’t really getting out there. I was too shy, really. Then one evening sitting at my desk, I sort of came to myself while I was trying to write some very poetic thing. Suddenly I asked myself, what about my actual life? What was my actual life?

I was living with roommates in a flat in the inner Sunset scraping by in a job I hated. I had no prospects for any career and didn't really know what I was going to do. Was poetry really it? There I was trying to create a great piece of wisdom for the ages and I suddenly saw myself as being really sort of lost. It was such a contradiction that, in that moment, I resolved that I wouldn't write anymore until I was able to really stand under myself. I would really have under-standing. My vision would have to reach all the way down to the ground. There wouldn't be such a gap between this grand vision and the fact of my actual life.

I've only slowly begun to write again in the last fifteen years or so, and I don't know what to call myself since I give myself permission to pursue whatever moves me—that is, without being stupid about it.

Robbin: It strikes me that one of the things you've done, and that you do very well, is the interviews you conduct for the magazine. Maybe that's a way of kind of engaging again without having to necessarily pull it all out of yourself, but instead elicit it from others and then incorporate it, make sense of it somehow—because you do shape the interview, and you are very engaged. That's one of the things you do so well in these interviews; you’re very curious about the person you're interviewing, and you ask searching questions. It seems to me that's a way of getting back into it without having to pull it all out of yourself.

Richard: That's very astute, Robbin. What you're saying is true, and I'm actually quite aware of that. I'm thrilled when a person I'm interviewing puts something into words that’s profound and wonderful—and true. It’s not altogether different from my having said it myself if I’ve had a hand in helping bring about the articulation of something deep and true. I'm always just absolutely delighted with that. It's what I hope for in an interview.

Robbin: Well that really is the nature of conversation, isn't it? It's not about two people sort of taking turns doing a monologue, but it's shaping something else between the two of them.

Richard: Yes, in the best sense. But how often does that happen in ordinary exchange?

Robbin: But it's such a delight when it does!

Richard: Indeed! And it’s not unusual when I talk with an artist and ask probing, possibly “stupid” questions, for the artist to say, “My artist friends and I never talk about these things!”

There’s something paradoxical about that. I think that in order to have a real exchange people actually have to cross a line, even a little bit, into sincerity. My experience is that it doesn't happen too often in day to day life.

Robbin: But don't you feel that it does in the magazine?

Richard: Well, yes! Very much so. It’s the reason for doing the magazine. Getting down to what’s really meaningful. Absolutely.

Robbin: To get back to the photography a little, can you say anything about what attracted you to taking pictures or what you hope to do with that?

Richard: I was living in San Francisco and was crossing the Bay Bridge toward Oakland. The sun was setting behind me and I could see the reflections of the sun off the house windows in the East Bay Hills, like diamonds. It was one of those late afternoons—maybe the car windows were rolled down with the marine air coming in, and I was in one of those moods with such a feeling just being alive in such a world of beauty. Then out of the blue, I wondered “What would happen if I took a photo of those East Bay hills lit up with those late afternoon, diamond reflections? When I looked at the photo, would the same feeling come back?"

So I got a camera in order to find out. That was in 1976, and I started taking photos to see if something of that feeling could be captured in the photo.

Robbin: Do you feel that you have from time to time?

Richard: I have. It's not so easy to capture even a little of that magic. I'm talking about something that's like an ecstatic experience - almost religious - in response to beauty.

Robbin: You mean at the time you were taking the picture?

Richard: Yes. Sometimes I see something that calls to me and as I get closer it opens into something magical. I have to find the composition as I'm moving around - like "how to capture this? - knowing it's there - and I'll be in this state sometimes verging on desperation because the light is changing or it's some orther fragile situation. These things don'r happen that often, but often enough.

Then when I’d pick up an art magazine and read these intellectualized things – this was back in the early 80s - I really couldn’t take them seriously. So I think the main impulse behind starting the magazine was to create a space for the recognition of the kinds of deep experiences I knew in myself, and which I wasn't seeing out there in the art world.

Robbin: And yet you are interested in ideas. You mentioned that you have a degree in philosophy. You still are very involved in philosophical issues and ideas.

Richard: You could say so. What's interesting to me are ideas and deep questions we face being alive in this mysterious existence.

Robbin: Well, where do you see your interest in art and philosophy intersecting? When you talk about having an ecstatic moment where you see something that is really, really beautiful and profound, I mean, in itself, you wouldn't have to explain that any further. That's a phenomenon that needs no explanation.

Richard: Yes. It's true that "regular people" understand that. Most people, when you ask them about art, use words like “beauty” and “truth.” And it’s clear they haven’t been to art school. But I think they’ve got the right idea. So where do art and philosophy meet? It’s like the question "Where do ideas and experience meet?"

Robbin: Yes.

Richard: They meet in the realm of experience - the realm we live in. But strangely enough this is always being missed. Somehow we’re convinced that we live in the realm of things. We're convinced that the rock-bottom truth of the world is "things" - materialism. But matter exists for us, first of all, in our consciousness of it. And the problem with the realm of experience, of consciousness, is that it eludes the grasp of our scientific materialism.

So where does philosophy fit with all this? Hard to say. Heidegger wrote about how the advent of science was the end of philosophy. I don’t think he believed it was really the end of philosophy.

But I'd say that art, at its best, is operating in the realm of being, which includes the realm of feeling. Feeling can even be an avenue to knowledge. But it's not so simple as it sounds.

Music gives us feeling, and everyone is feeding themselves with their radios and iPods. But I don't find much in the visual arts that really is trying to remind us of the transformative realms of our experience. There's plenty of work that can upset us or point toward problems, but not much that's pointing toward the more mysterious in life.

Robbin: I don't know if you'd agree with this or not, but I see around us the cell phones, the iPods, the individuals driving alone in a car and, too often, I am one of them. One thing that strikes me about this in relationship to art is that it seems the participation in art - whether looking or listening, or actually engaged in making it - has, in the past, been much more of a communal experience than it is now. It used to be that you’d go to concert and there would be actual human beings there.

It seems to me that something different happens when you're listening to a live performance instead of to a recording. It seems that even in the visual arts there used to be these enterprises that many people would be engaged in - for instance in western art, in making a cathedral. Much of that is lost to us now.

Richard: Something is happening there, for sure. That's a very interesting and troubling question. I don't pretend to have the answers, but I think it's interesting when Jean Baudrillard says that art is no longer able to perform a vital function in this culture. I don't say that to demean anything in this room, and I'm doing an art magazine myself, after all. But I feel there's something to his observation.

I interviewed Paolo Soleri, the visionary architect, several years ago. He's probably close to 90 now. Late in his life he came around, for some reason, to accepting the proposition that computers and artificial intelligence will lead us to the next step in evolution. We humans will be left behind. As he put it, "maybe humans will be like pets for the new, higher silicon life forms."

Robbin: Because of the computer?

Richard: Yes. I found it pretty disturbing that Paolo Soleri had embraced this belief. Everything I'd learned about him seemed to point in an opposite direction. Yet there's a world of people completely serious about this proposition that some kind of cyber intelligence will replace us on the ladder of life.

So one of the things I wonder about is how you bring, let's say, a moment of the numinous to life when a lot of people are embarrassed even to ask deep questions nowadays?

I tell this story I heard from Jacob Needleman. He was asked to teach a philosophy course for high school seniors. He met with the class for the first session, all very bright kids, and said, “Imagine I'm someone you can ask any question and I’ll be able to answer it.” He gave them ten minutes to write their questions down and pass them up to the front. No names attached.

He got the papers back and the questions were mostly trivial except he noticed that a lot of students had added question in margins of the page. It was like after the trivial questions had been written then some real questions began to appear. “Who am I?” “What is my purpose?” “Is there a purpose?” Those deep questions were literally marginalized. Today, who needs them? We have plenty of entertainment. Maybe people think we're beyond all that deep stuff.

Robbin: Well, it's interesting. You say that you're mistrustful of the New Age and I tend to agree with you, but what is it that's so disturbing?

RW: That's a good question. There's something that Chogyam Trungpa called 'spiritual materialism' - the idea that I can possess the higher aspects of life as if they were products. In all the traditions, there would never be any confusion between buying a new car and trying to open oneself to the realm of deeper truth, let’s say.

We seem to have gotten used to the ubiquity of hype. When I hear someone say, “It’s the greatest something or other in the history of mankind” I figure, well, maybe it's halfway good.

Robbin: And you know it's going to cost you money. But getting back to the magazine. How do you make decisions about who you’re going to interview or what the topics will be in each issue of the magazine? I'm impressed by how cohesive each issue seems.

Richard: I always say, “it’s an organic process.” I might have one or two pieces at the beginnin - an interview or two. It's like going through your day. You never know exactly what's going to happen. You pass all kinds of people on the street. You listen to the radio and, who knows? You might hear something you didn't expect. It’s how I ended up interviewing Godfrey Reggio who made the film Koyanisqaatsi. I was listening to KQED and he was being interviewed. He was in S.F. so I called the station. It’s almost miraculous that I got to spend an hour and half with him the next day.

Each issue is like a blank canvas. I never know what the theme will be in advance. It just appears out of what I encounter and what resonates. Somehow I always manage, after six months, with another issue.

Robbin: So it takes you six months to develop an issue?

Richard: Yes. It used to take nine months [laughs].

Robbin: [laughs] That's a nice biological period. But is there anything that you can tell us about the kinds of things that strike you or capture your interest. I think there are a lot of artists here who would like to know.

RW: I can give you an example of something I'm going to publish and how it came about. Ruth Braunstein wants to do a book on Richard Shaw and asked me to interview him for the book. So several weeks ago some of us met at Ruth’s gallery to brainstorm about it. But before we really got into it, Shaw’s daughter, Alice says to Ruth, "You should have seen where I took my dad before I brought him to the meeting." Several conversations were going on at the same time and I couldn't hear all of it. But I heard something about “this amazing park' where some fellow, who works for the city, makes great things." Then we all got involved in the catalog project and I didn't get to ask Alice Shaw about it.

But I remembered those fragments and a few weeks later I pieced a few clues together and found this place, a San Francisco city park on Cayuga Street. Nobody was around so I walked around and was amazed to find all these carved wooden sculptures tucked in here and there - at least a hundred, all outsider art. I’d never seen anything like it in a public park.

I saw why Alice had been enthusiastic. And I thought I’d heard her say something about “a little Asian man.” So I went back a second time. This time I saw a little man pushing a broom over in a corner. He didn’t look like someone in charge. But who knows? I had to find out. So I went over and asked him a few questions. Turns out he takes care of the whole park. So I asked him, “Are you the one who has done all these sculptures?”

He looked down sort of embarrassed and said, “Yes.” [laughs] Demetrio Braceros. He was so incredibly humble. I knew right away I wanted this in the magazine and I hoped he'll let me take his picture. I mean this was just a magical, pure thing. I did a whole article about him. And how did it happen? Just because I’d overheard something. So there's one example.

Robbin: That sounds like amazing serendipity. A few minutes ago you said something I found very depressing, that art didn't function the way it should anymore. But I don't think you really believe that, because why would you devote your life to bringing an art magazine to fruition twice a year if you did? So maybe you can give us something of a more positive nature, why art is important. Why it might be important.

RW: When I said that I was quoting Jean Baudrillard and I said I understand why he says that. I think there’s some truth in what he says, but I don't think it is the absolute truth. But why is art important? I'm really old-fashioned because I remember the phrase, 'art, philosophy and religion.'

When I was in my twenties you’d run across that phrase. I haven’t heard it in ages now. There are a lot of very sophisticated things that go with art today. The schools handing out MFAs have to have something to justify all the money it costs. So you can become 'an expert' and talk semiotics, memes and tropes, and valorize cultural relativity, gender issues and so on.

Art used to be more widely regarded as a possible pathway to the numinous—something that comes from another level. Richard Shaw was telling me about his experience of looking at a painting a few days ago in a Portland museum. There was something about it, he said, that was so alive. Something about it just hit him, it moved him. He's still thinking about this painting. It's an example of what art can sometimes do. It can be a magical thing, but this magic is not easy to reach.

If I happen to have a moment where I'm touched this way, it immediately reminds me that there’s more to living than our usual day-to-day business. I forget that all the time. We all forget that there's something like another level—these amazing moments where we feel suddenly much more alive. A moment like that brings meaning. It's hard to put this into words. One is reminded how this is actually mysterious, this world, and that I am here alive.

I think that art sometimes touches one on this level. It's rare. It's beyond anyone’s ability to just turn out a piece of art like that. I love the way Agnes Martin writes about art. She says that the life of the artist is a life of suffering. It’s because the artist can’t achieve that. There’s failure after failure. But then somehow, something magical happens. As Agnes Martin puts it, it's a “moment of perfection and suddenly the road ahead is clear. There’s order. There's meaning." But it only lasts a little while and then it's gone. The memory of it keeps you going. So that’s an example of something that can happen in the arts.

Robbin: I was reading a quote that's attributed to Beethoven. He said, "Please let me just live long enough to have a moment of pure joy." That seems to express, in another way, what Agnes Martin is talking about. Beethoven!—one of the most sublime composers of all time. So what is it that artists do?

RW: That’s an essential question. What could that pure joy be? It occurs to me that there’s no career path for becoming one's real self like there is for becoming a lawyer or a doctor. My hunch is that on some deep level artists feel a hunger—consciously or unconsciously—for something like that. With writers there's the understanding about the importance of finding one’s own voice.

So what would that be, finding one’s own voice? I think the artist has that same essential search. There's no job description for how to get there. You don't get paid for it. And one of the big confusions in art is around money and this other thing.

Of course, there are many different directions people can go in the arts, but to me the most interesting thing is how it relates to this essential search. So what about this part of life one has read about? Pure joy? People have experienced miraculous things. I think the artist feels some sort of instinctive hunger for a real life, let's put it that way. A real life.

About the Author

Robbin Henderson is an artist. She was the director of the Berkeley Art Center from 1991 to 2006. Her book, Immigrant Girl, Radical Woman was recently published by Cornell University Press.

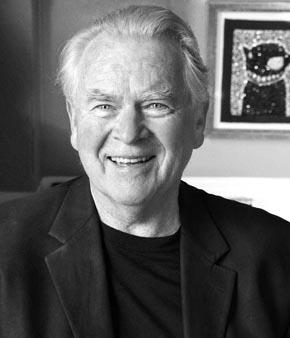

Richard Whittaker is the founding editor of works & conversations and West Coast editor of Parabola magazine.

SUBSCRIBE NOW

TO OUR MONTHLY NEWSLETTER

Share Your Comments and Reflections on this Conversation:

On Jan 19, 2020 heide toner wrote:

i feel connected to this interview .... there is an interesting easy personality test you can take called “16 personalities.com. I discovered something that offered me some comfort in feeling not always in sync with the modern world or the predictions for the future. My personality type is “the protagonist “I am always truly happiest with people and when those people are at their happiest or most content... we comprise a small population of the pie and it helped explain why sometimes I feel like it’s hard to find others who understand how I see the world. When I use myself as a conduit to help others they appreciate it are Sometimes as bewildered as they are grateful. This interview felt like I was listening to two fellow protagonists ...Maybe we are not lost. Maybe everyone else is.On Mar 14, 2018 Gillian Lasker Lourenco wrote:

A friend of mine shared this with me. I thank you. I would say/ask one thing with reference to the question of searching for one's real self and the use of art, and I would love to hear some opinions on the subject in a magazine such as yours: What about the work of Art Therapists? I am 62 doing a Masters in Art Therapy - to change my profession, and finally to "come home". My journey in this process has been one of searching and finding those moments of 'my real self' and I am changed. The more I have learned the more I believe in the use of art for this process and in the use of art as having a significant role in this. I would love to hear others' opinions on this, or something of their journey. Again thank you.